— Photo from the Guilderland Historical Society

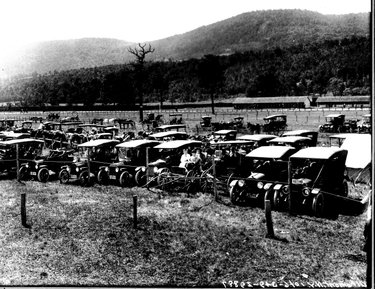

The parking area at the 1916 Altamont Fair showed that there remained a sizable number of horse-drawn rigs on the road, but that they were rapidly being replaced by automobiles. With the production of modestly priced Ford Model T’s and less expensive used cars for sale, more and more of the state’s population took to the road in an automobile.

Martin Blessing’s cry, “Hurry out! A horseless carriage is coming by,” alerted family members to rush out front of their farm in Fullers where, frightened by the commotion, his small daughter peeped out from behind her mother’s skirt as the strange contraption rolled by.

Anna Anthony, recalling this event in her old age, never forgot her first sight of a car. Perhaps it had been the Locomobile Steamer that Arthur Barton, living on a farm a few miles west on the turnpike, remembered as his first car, describing it as “a wooshing, bouncing carriage-like affair careening ‘madly’ down the old plank road in a cloud of dust and steam.”

Even those who had not yet seen an automobile were aware of their development after reading articles such as “The Horseless Carriage” published in a September 1899 Enterprise. As the first decade of the 20th century unfolded, more and more attention was given to local automobiles and their owners in the pages of The Enterprise.

Owning a car in that era was not for the faint of heart. City folk seemed to become car owners before those in more rural areas and it seems out-of-towners were the first to pass through Guilderland.

In 1904, Mr. and Mrs. Tompkins of New York City stopped by in Altamont while on their way to their summer home near Berne, disgusted that rain had delayed them in the mid-Hudson Valley when the normal running time between New York City and Albany would have been 12 hours.

A year later, they arrived with another couple in a second car headed for Berne when, as they climbed the steep hill out of the village (now Helderberg Avenue), the Tompkins’ auto stalled, brakes failed, car began rolling backward, wife jumped out, and husband ended up partly overturned against an embankment. No injuries to either, car righted, cranked up the engine and they were on their way.

That same year, intending to visit his sister, Mrs. E.H. York of Guilderland Center, George Crounse’s engine died in Gallopville, causing the humiliation of having to hire a farmer and team of horses to tow him to Altamont where he had to telephone to Albany for “a professional” to come out to fix the problem. Not only was driving an automobile an adventure, it was an expensive one!

And already in 1906 the folks in Guilderland Center were outraged at “the speed autoists make through the streets of our village. Some estimate the rate at 60 miles an hour, some 40 and some 30 or 20.”

Early automobiles had to be hand cranked to start (electronic starters were in the future); had limited horsepower; were forced to travel for miles on wretched roads, causing frequent flat tires; and, outside of cities, there were very few places to buy gasoline or find mechanical help.

A few of the very early cars operated on steam power, which had its own set of problems. And of course, none could travel in winter before antifreeze.

The identities of the first car owners in Guilderland are unknown, but by 1906 Altamont’s Charles Beebe’s and W.H. Whipple’s drives were noted in The Enterprise. There were surely others. “Auto parties” were noted at that time, passing through on their way to enjoy the amenities of the Helderberg Inn.

Sands’ Sons

Eugene and Montford Sands got it right when they stated in one of their Sands Sons’ advertisements: “The automobile is here to stay.” Already successful Altamont grain and coal merchants, the two entrepreneurs opened an auto agency in 1907.

An early offering included for $275 a Success runabout (a two-passenger open car) featuring a “powerful” 4 horsepower engine with wheel steer (several very early cars had tillers for steering) or for $600 a Federal runabout with a 15- to 18-horsepower engine.

For a big spender willing to part with $1,250 the Model B, a 24-horsepower, two-cylinder automobile with a removable rear seat that could carry five persons — “a wonder for the price.”

During the early automobile years there were many companies manufacturing cars with brands that within a few years were out of business, making their names unfamiliar today. Among the automobiles acquired by local men were Reo, Overland, Locomobile, Columbia, Brush, and Great Western.

Sands advertised others such as the Success and Model and it’s assumed that they were purchased by local drivers. Fords and Buicks were also locally owned as well.

By 1908, automobiles’ popularity was firmly established, appearing on local roads with increasing frequency. Sands Sons cleverly whipped up enthusiasm for the new technology not only with announcements and advertising in The Enterprise but also by exhibiting automobiles at the Altamont Fair where the brothers touted the merits of the new 1909 Great Western five-passenger touring car to over “200 prospective” buyers during Fair Week. The village and town column announced that Messrs. Clikeman acquired one of them.

Earlier in May 1908, the two car salesmen had focused attention on the trophy won in Menands, their Great Western coming in first for the fastest time in its class for five-passenger $1,250 cars in a steep hill-climbing contest.

Soon they were promoting a new $1,600 Great Western 30-horsepower model that had the advantage of being converted into a gentleman’s roadster by detaching the tonneau and substituting a rumble seat.

Their sales pitch ended with, “Watch out for this car as it will create a stir among auto enthusiasts.” And the really affluent man with an extra $3,500 could drive away from their dealership in a 50-horsepower Great Western.

However, the automobile that really caught on because it was inexpensive and rugged, becoming the most famous of the early autos was Ford’s Model T. It stood high off the ground, allowing the sturdy vehicle to maneuver over rutted country roads giving it appeal to rural drivers.

Aware that only a limited number of local men were wealthy enough to purchase a large touring car, Sands’ Sons introduced a two-passenger Brush runabout, claiming the runabout not only had gas mileage of 25 to 40 miles, but that a woman could drive it easily.

These two car salesmen assured prospective buyers this “very neat and easy running car” was capable of climbing any hill in the area, announcing an Albany dealer had plans to drive a Brush up the Capitol steps. New York state authorities put the kibosh on that publicity stunt and it never happened.

Many years later, it was recalled that sometimes the Brush ran well; other times the engine made a hill climb sputtering, “I think I can, I think I can, I thought I could, I thought I could … I can’t!”

Erecting a big tent at the 1910 fair, the Sands continued to push the Brush, assuring would-be buyers that, if they made a purchase during Fair Week, Sands would give them a “special figure.” Current Brush owners were invited to use the tent as their fair headquarters.

Two people who at some point purchased Brush runabouts were Eugene Gallop, who was the mailman on a rural route, and Irving Lainhart, who delivered groceries in his Brush until 1918 when he traded it in for a Ford.

In addition to selling cars, Sands’ Sons also advertised that they had supplies of batteries, lubricating oils, gasoline, etc. for automobile owners and chauffeurs. Automobile owners of the era were a versatile group changing their own tires and dealing with simple mechanical problems, but for things more serious a mechanic was needed.

The demand was quickly met in 1907 when Mr. James Bradley opened up a shop in the rear of Lape’s Paint Store in Altamont, advertising himself as an experienced mechanic who could repair automobiles.

Problems arise

At this time, Guilderland’s large population of upset, unhappy horses (and their owners!) were usually terrified when approached or overtaken by these noisy, smelly behemoths especially since the roads were very narrow, putting car and horse in close clearance of each other.

Guilderland Center’s F.C. Wormer ended up painfully, but not seriously, hurt when his horses, spooked by a passing car, took off, dumping the unfortunate F.C. in the road.

As Dr. Fred Crounse was driving his auto to Meadowdale, he began passing Cyrus Crounse whose skittish horses became so terrified by the car, they rushed toward it and one ended by jumping on part of the car, “smashing some of the fixtures on the driver’s side. A few dollars in repairs made the machine as good as new,” but no mention was made whether they were Dr. Crounse’s dollars or Cyrus Crounse’s.

As automobiles proliferated another problem became obvious.

Again in 1907, the Guilderland Center correspondent wanted to know why there was no speed limit out in the country, claiming that the previous Sunday morning “there came tearing down through the Centre an auto at a velocity of speed that would put a western cyclone to blush,” showering people on their way to church with dust and grit and endangering the children.

On another occasion an auto driven “wildly” through Guilderland Center struck and killed Seymour Borst’s pet dog. Again there was a call for more strict laws against those “speed fiends who rush madly down our streets.”

Automobiles had become a permanent part of childhood experience. Marshall Crounse, the 9-year-old son of Dr. and Mrs. Fred Crounse, ran in front of a car while on vacation with his parents in Florida and was knocked down with at least one wheel rolling over his legs just below his hips. Miraculously escaping serious injury, Marshall was fine by the time of his family’s return to Altamont.

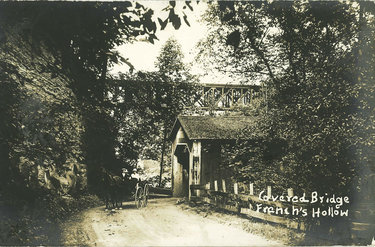

Ten other children had a more positive experience when Mrs. David Blessing, their Sunday School teacher, arranged for Montford Sand to cram all 10 into his big touring car for a drive to a picnic at Frenchs Hollow.

The danger of fire became evident. A very expensive touring car driven by summer cottage owner Gardner C. Leonard’s chauffeur burst into flames a mile and a half east of Altamont. The chauffeur threw himself out of the car just in time for, when the fire was out, the only thing left were the two front wheels.

The frames of those early cars were of wood, causing them to burn rapidly once the gasoline was ignited. When another auto fire destroyed a vehicle on the Western Turnpike in what is now Westmere, it was noted the owner had insurance.

“Death in Auto Accident” headlined the most tragic fire in 1911 when Mrs. William Waterman, out with her husband for a drive near Altamont’s Commercial Hotel on the Main Street, suddenly screamed she was on fire.

Her light summer clothes quickly blazed up, resulting in her death the next morning. Although The Enterprise reported the cause of the fire was gasoline, the car itself didn’t burn.

Many years later, a recollection of the incident claimed the car was a Locomobile Steamer, an early car where paraffin or naphtha provided the fuel for the fire to heat the water to make steam to power the automobile. These impractical cars quickly went out of production.

One August 1911 morning, William Whipple, driving the Sands’ autotruck, pulled out of Altamont carrying Montford Sand in the passenger seat. While traveling down “church hill” past the entrance to Fairview Cemetery (now Weaver Road) the autotruck encountered two women approaching in a horse-drawn buggy.

The skittish horse panicked and, jumping into the ditch overturned the rig, throwing the women out. Seeing their plight, Sand immediately leaped out of the autotruck, stumbled and fell, striking his head. Unconscious, he was carried back to his Altamont home where he died hours later.

The dangers of automobile ownership had already become apparent and it was a tragedy that Montford Sand, one of the brothers who did the most in the very early days to popularize the automobile in Guilderland, died in an automobile-related accident.

As the numbers of cars on the road increased, the death toll from auto accidents began to rise. In Guilderland, the two most dangerous spots were at the intersection of the Western Turnpike and the Altamont-Schenectady Road (now routes 20 and 158) and at the railroad crossing in Guilderland Center.

By 1916, statistics showed that there were 300,000 motor vehicles registered in New York state alone and reports had come in of the decline in earnings for railroad passenger lines. As new careers for mechanics, car salesmen, and car-related businesses opened, businesses related to horses and horse-drawn vehicles declined and eventually almost totally disappeared. A technological and transportation revolution had begun.

When last did you write or receive a picture postcard?

Modern technology’s new communication methods have made them a thing of the past. However picture postcards of the past have proven to be a valuable resource, adding to our knowledge of long-ago scenes.

Recently, the children of the late William P. Chamberlin donated his postcard collection of local views to the Guilderland Historical Society. Included in his carefully organized and notated collection were some views never previously included in the society’s archive of photographs and postcards.

In 1873, the United States Post Office introduced postal cards printed with an image representing the one-cent postage and space to write the address on front and a blank back for the message.

Picture postcards were introduced at Chicago’s 1893 Columbian Exposition, catching on with fairgoers immediately. At first, United States postal regulations slowed their use, but by 1901 private printers were permitted to call them postcards.

However, messages were not permitted on the same side of the card as the address, resulting in only a tiny blank spot for a greeting or brief message on the picture side. Finally, in 1907, the Post Office began to permit the back to be divided for both message and address. At first, the postage was the same as a first-class letter, but later reduced to one cent.

Several factors led to the production of millions of postcards up until World War I. Kodak had developed a folding, portable camera, allowing men to visit a community or scenic spot to quickly snap prominent buildings and scenes or to travel to parklike settings, and in this area the Helderberg escarpment that became Thacher Park was the big attraction.

Two photographers who captured many views of Guilderland locations were Parker Goodfellow of Schenectady, who was supposed to have taken a total of 32,000 views as he traveled far and wide and Binghamton photographer John Dearstyne who shot some as well. Others are unidentified.

In addition to views, holiday postcards produced for Christmas, Easter, Halloween, and Valentine’s Day were popular. Other types of postcards were comic cards and cards featuring important people such as a patriotic George Washington card.

With the frequent rail service hauling attached mail cars, which delivered mail as often as twice daily, in many areas along rail lines mailing a postcard became a rapid means of communication with short messages of the “come quickly, mother is ill” or ”I will be arriving on the 4:22 train on Friday” variety.

The public not only mailed millions of postcards, they collected and mounted them in albums designed to display them. This is the reason why so many antique postcards are blank, intended only for an album.

Because postcards were inexpensive, most people could afford them. In 1911, L.S. St. John , an Altamont news dealer, advertised six new Altamont views at two for 5 cents or five for 10 cents.

Postcard “showers” for special occasions or illness were regularly mentioned in Enterprise columns. One man, having just celebrated his 80th birthday, put a card of thanks in the Enterprise to thank everyone who has sent him a total of 90 cards.

In 1913, the U.S. Post Office claimed a total of 900 million postcards had been mailed in this country.

Since huge numbers of the higher quality cards were printed in Germany, once World War I began, the supply of cards diminished, and gradually the telephone began to take the place of brief communications.

With that, the postcard lost popularity. Although postcards continued to be printed during the 20th Century, the local photo cards, especially of smaller communities, were no longer produced.

Fortunately, because so many of the old postcards were saved and have survived into the 21st Century, we are able to look at our communities as they once were.

Hometown Heroes, honoring men and women who have served in our nation’s military, has become a Guilderland tradition. Family, friends, or organizations have the opportunity to submit the name, branch of service, dates, and photo to be displayed on a banner at Tawasentha Park from June through November.

Sponsored by the Guilderland Historical Society, a banner honors Luther C. Warner 2nd, an ambulance driver in 1917 and 1918 who saw action during World War I. After returning in 1919, he became one of the charter members of Altamont’s American Legion Helderberg Post 977 at the time of its organization in 1924.

Luther C. Warner 2nd, to distinguish him from his uncle, Luther C. Warner, at that time very prominent in Albany County Republican politics and county clerk, was the son of Mr. and Mrs. Arthur Warner of Berne. After attending elementary school Berne, he transferred to Altamont High School, graduating in 1913, next attending Cornell University.

Although World War I began raging in 1914, the United States did not enter the war until April 1917. At the initial outbreak of the war in 1914, a private group called the American Field Service organized and recruited many college men who volunteered as ambulance drivers to aid the Allies.

Once the United States entered the war, Luther C. Warner volunteered shortly after as an American Field Service ambulance driver. Quickly arriving in France, he was assigned to the French army by July 1917.

A prolific correspondent, many of his well-written, lengthy letters were reprinted on the front page of The Altamont Enterprise. He reached the front months before other local men in the Allied Expeditionary Force, as the American army was named during this conflict, were recruited, trained, and transported to Europe, so his early letters were the first eye-witness accounts reaching the newspaper’s reading audience.

Training

Initially his letter of Aug. 23, 1917 found him 40 miles from Paris, but only 25 miles from the front lines. Even at that distance during heavy attacks, the roar of the artillery fire was audible especially at night when light from bursting shells and bombs could be seen. “There is at present a great attack on Verdun with the French on the offensive and they have gained some ground ….”

This letter noted he was practicing driving, compared French and American engines, and was hoping to have a Ford “car,” which we have to assume was fitted out to be an ambulance. Simple repairs were also part of the training.

After recounting his daily schedule, he described at length the architecture and agriculture in this region of France. A week later, he was still in training camp expecting to return to Paris briefly before being sent out to the front lines.

A second letter “Warner Writes Again” appeared on the front page. By early September, he had finally arrived at his section where they were doing evacuation work, carrying convalescents from one hospital, probably close to the front lines, to another, probably further back, but so far he had not carried anyone just wounded in the Ford ambulance he was driving.

Traveling at night when it was less dangerous than daytime, no lights were allowed so that drivers navigating roads pocked with shell holes in the dark made it a different set of dangers.

He mentioned that some towns in France seemed untouched by the war, but that others were seriously damaged, mentioning that two nights ago a “Boche” (German) plane dropped a few bombs on a small village nearby, killing 20 persons. He ended his letter with the information that he would soon be moving to a post near the front “where things will be more exciting.”

His next letter written “somewhere in France” appeared on the front page as usual. This letter was actually written Sept. 15. He wrote that cars had to be kept in running order, ready to leave on a call at a moment’s notice. Expert mechanics were on hand to deal with serious problems, fixing a broken axle for instance.

On a personal note, Warner wrote that he had purchased an inexpensive pocket Kodak in Paris and in future letters noted taking photos although photographing in the war zone was forbidden. Most of his photos would be of agricultural subjects.

“Very anxious”

Within a week, they were to move within two miles of the German lines. “I am very anxious as I know it will be very interesting and exciting.” Then he described his “section” which included 20 ambulances, a staff car, two vehicles with French names, a reserve supply car, an American leader, a French Lieutenant, orderlies, a sergeant, a cook, mechanics, and a few helpers.

A tale of a scary experience ended the letter. The Frenchmen accompanying him supposedly knew the way on a dark night, navigating a road full of shell holes six feet across and one to three feet deep. Following the Frenchman’s directions even though Warner had misgivings, they found themselves hopelessly lost.

After getting out, walking, and finally getting directions, they eventually reached their hospital destination, discovering that at one point they had come within a few hundred yards of German lines.

When will the Americans get here and in the trenches was a question he heard repeatedly. Almost every Frenchman under age 50 was in uniform. War weariness and exhaustion were prevalent.

Leading off another of the Enterprise’s front pages was a riveting letter detailing his up close and personal view of a German plane crashing. Apparently trying to photograph the location of the French artillery and supply area for information to aim their artillery’s shelling, the plane, likely hit by French fire, went into a spiral.

As the pilot attempted to keep control, it turned upside down, the pilot managing to right it again. After spiraling one or two more times, the plane plunged straight into the ground, the impact killing the two Germans on board.

The French claimed the engine to possibly be reused, while everyone tried to get a piece of the plane as a souvenir. Warner got the job of taking the two dead Germans to the site where they would be buried.

He commented that the Germans had no visible injuries, probably dying of internal injuries. He noted, “I have carried men in my car suffering from (poison) gas and shell wounds who were a more pitiful sight than these two fellows.”

Trenches

For quite some time, none of his correspondence appeared until May 17, 1918 when a letter to his sister appeared. Still in the same area where he had been since January, Warner described the trenches where they spent most of their time when they weren’t on duty.

Most were 10 to 20 feet below ground, but his location was 39 feet below. The lines were exactly the same since April when the French pushed back the Germans.

Descriptions of the sufferings of civilians show up throughout his letters. The wreckage of villages where the stone and stucco buildings have been shattered by shell fire is mentioned several times in various letters.

Women and children in one area starved and suffered from winter cold because of a regiment of men raised from their city, ages 19 to 50, only four came back. The remainder either were killed or died later of wounds.

With the beginning of the Second Battle of the Marne in June, the Germans began an offensive aimed at Paris. Warner commented, “The saddest part of this retreat is to see the French refugees fleeing with what little baggage as they can pack on a cart or baby carriage or on their back … the little children walking for miles and miles.”

His last letter to be published was July 12 when the Second Battle of the Marne had begun, one last desperate offensive by the Germans to take Paris. When Warner wrote, it seemed as if the French were in retreat and their only protection were trenches they could dig in a short time.

Dressing stations for the wounded kept being moved, making it more difficult for the ambulances to find. “We have heard of cases where drivers continued on their routes and ran right in the Boche lines. We wear Red Cross brasses which entitle a man to be exchanged if captured.”

Wounded

Ironically, days after his letter’s publication, he was wounded. On July 26, an Enterprise front page notice announced, “Luther C. Warner, 2nd Wounded By Hun Shell.”

A telegram received by his parents said he was “slightly wounded by shell fire in charge of his duties.” Days after his wounding, Warner’s commanding officer Lieutenant Elliot H. Lee sent a personal letter to his mother detailing the circumstances; this was later published in the Enterprise.

While German bombardment was at its height, “Luke’s Car was riddled with eclat (pieces of shrapnel), all the tires being ruined, the radiator being punctured, spokes broken … Luke started with Varney to go on foot to a post on the other side of the river … their route lay through a wheat field very heavily shelled and both had to drop on their faces again and again. Finally one shell came very close — Varney dropped in time, but for Luke it was too late.”

Warner had a broken arm, fingers cut, and his leg hurt so he was unable to walk. His companion ran for help, returning with men who got him back to the post so he could be quickly evacuated to the rear.

Lt. Lee noted that throughout Warner “evidenced the finest spirit of fortitude and courage” with the chief of medical service recommending he be awarded the Croix de Guerre. Luther Warner was, indeed, awarded the Cross of War, a French medal recognizing heroism during combat. Earning one was considered a great honor.

Coming home

World War I finally ended on Nov. 11, 1918 finding Warner “alive and well” along with several local soldiers listed in The Enterprise in December. Because the United States did not have the capability to transport the huge numbers of American veterans home in a hurry, concern began to grow about their increasing discontent, anxious to get back to normal lives.

Led by Lieutenant Colonel Theodore Roosevelt Jr., officers and soldiers met and organized what they called the American Legion at a meeting in Paris on March 15 and 16, 1918. It was chartered by Congress on Sept. 16, 1919. As the men returned home, American Legion chapters began to be formed.

Warner’s return home was noted on page one of The Enterprise in a separate notice. He quickly completed his college degree and, in 1923, married Margaret Kirk of Altamont, settling down in the village where he spent the remainder of his life.

About this time, he began to work at General Electric, receiving many promotions until his retirement at age 65.

He was likely one of the “boys” who showed “considerable enthusiasm” at the November 1924 meeting to organize Altamont’s Helderberg Post 977 of the American Legion and is considered one of the group’s charter members.

During the remainder of his life, Warner found time for community service, at various times serving as an Altamont Library trustee, on the Altamont School Board, and as a village trustee. He was also very active with St. John’s Lutheran Church as well as Noah Masonic Lodge.

Luther C. Warner represented the best in our nation, willing to defend it in time of war and working to make his community better in time of peace.

Author’s note: Credit for initial research about Luther C. Warner 2nd goes to Kathleen Ford Gaige with input from his nephew, Homer Warner, during her research on the charter members of Helderberg Post 977 at the time of their centennial in 2024.

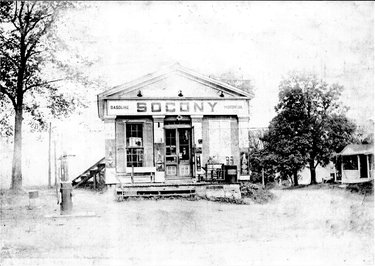

— Photo from the Guilderland Historical Society

Ward’s Store dated back to the end of the 19th century. The Carpenter Bros. and H. & E. Olenhouse, previous owners, delivered groceries by horse and wagon and ran a stage back and forth to Albany, picking up the community’s mail. Olenhouse also installed a phone in his store in 1911, the first owner to take orders over the phone. Beginning in the late 1920s, it became Ward’s Store, continuing as a post office until 1961 when a separate post office was erected. The W.G.Y. stood for a grocery wholesaler who supplied independent small grocery stores in those years. Note the 1920s gas pumps. Today this site is part of the Guilderland Fire Department property.

Glassworks along the Hunger Kill led to the birth of Hamilton, which the postal service later named Guilderland. The rest of the hamlet’s history unfolds in this week’s column.

Facing a major setback with the departure of Newbury Foundry on the eve of the 20th century, Guilderland’s villagers had to readjust to an economic impact from the loss of the payroll and the social loss of so many inhabitants including members of extended families who relocated to Goshen with the company.

For many years after, there were visits between Goshen and Guilderland as friends and family members kept in touch.

Fortunately, a group of local men invested their money in shares to buy the foundry property from Jay Newbury, reopening as Guilderland Foundry. Immediately resuming operations, the new management began advertising for additional help in the machine shop and foundry. They expanded its capabilities to cast aluminum and brass as well as plating with nickel.

Wired for electricity in 1920, the foundry advertised grates and parts for stoves with castings of fraternal emblems for cemetery plots and metal doorstops in production. Continuing to provide some employment in the community, the Guilderland Foundry never had workers on the scale of Newbury’s.

With the coming of the Depression in 1929, production ceased. One last shareholders’ meeting was held in 1934 followed a year later with the property foreclosed and up for auction. The buildings were taken down, eliminating all traces of their existence.

Churches

One constant in the community were the two churches, the Methodist Church on Willow Street with its parsonage nearby and Hamilton Union Presbyterian with its parsonage in front of the church. Each had its own minister until 1920 when, probably due to financial constraints, the two churches federated sharing one minister alternating years, renting out its parsonage when it was the alternative church’s ministerial choice.

Especially during the Depression years, financially keeping up the two church buildings became increasingly difficult. Finally, in 1944, Methodist Church members discontinued their church with 72 members formally transferring to the Hamilton Union Church. After this, the Methodist Church building was removed.

Not only providing religious services, the churches had a variety of organizations such as Willing Workers, Christian Endeavor, or the Missionary Society that offered an opportunity to socialize as well as serve some purpose.

Very often some sort of social event went on in one church or the other, each with a minimal admission fee to support the sponsoring church, but also providing a night out, especially important in the years before automobiles made it easy to go to a nearby city for entertainment.

Each announcement, whether for an early century gramophone concert, a chicken dinner, clam bake, or some kind of performance, the whole community was included with the note “all are welcome.”

After World War II, with the rapid growth and suburbanization of that part of Guilderland, the numbers attending Hamilton Union Church increased so that a sizable addition was built with Sunday school rooms and additional space for meetings. The parsonage building that once stood in front of the church was taken down and the area paved to expand the parking lot with a parsonage purchased nearby.

To the east on Route 20 was a small Greek Revival style building originally built in the 1840s for a Baptist congregation, followed by a Catholic church, which also left, leaving the building standing empty for some time.

Social life

Then, in the 1880s, the Good Templars, a temperance group, moved in, being joined in 1896 by a council of The Improved Order of Red Men, a fraternal order that patterned its rituals and regalia on what they considered Indian customs.

In Guilderland, male members were part of the Iosco Tribe, No. 341 and would have come from all over town, not just the hamlet of Guilderland. There were titles such as sachem, prophet, senior sagamore, and keeper of wampum, with ceremonies and rituals to be followed. Women were members of the Order of Pocahontas, Natoma Council also with rituals and titles.

The Red Men’s members enjoyed socializing, sometimes providing a community social activity for a small admission. Both were in contact with other local councils and IORM state officials such as the Great Prophetess. This organization eventually faded away, going out of existence in Guilderland in the later 1950s.

The small building, often referred to as Temperance Hall or Red Man’s Hall, was also used for civic functions. During both world wars, Red Cross meetings were held there with women volunteering to sew or knit needed articles for the troops. It also served as a polling place for the Guilderland Election District.

Finally, after the disbanding of the local chapter of the Red Men, no one was left to pay taxes on the derelict building. Abandoned and condemned, one night in 1967 it burned. Today a New York state historic marker marks the site where it once stood.

Schools

Guilderland’s elementary school, built in 1891 on Willow Street, had a near disaster early in the century when a terrible November storm blew over the chimney, sending chunks of masonry through the roof, crashing through a classroom ceiling, destroying several student desks.But for a teachers’ institute giving the children a day off from school, there would have been serious loss of life.

The building remained in use until after centralization and the 1953 opening of Westmere Elementary School. With the area’s rapid postwar population growth, the school building had gotten so crowded that additional space had to be rented for some classes so that by 1950 classes in that building only went up to the sixth grade.

The centralized school district sold the district’s redundant old school buildings with Guilderland’s being purchased by the town of Guilderland to be used as our town’s first real town hall. Instead of having town officials run the town from their own homes, there was now office space in a central location.

Eventually, when the current town hall opened in 1972, the building became a New York State Police substation; its side parking lot, decades before, had been the site of the Methodist Church.

The school bell that had called generations of Guilderland students to class had been taken down in 1953, and was sent to Greece to replace a bell in a church that had been destroyed in the war.

Fighting fire

People in the community became concerned that they had no nearby fire protection, having to depend on coverage from departments from other areas of town. Apparently by 1930, they began to make a serious attempt to form a fire company and by 1931 began holding meetings in Charles Bohl’s garage.

A year later, some equipment was purchased including hose, a hose cart, and three ladders. During the remainder of the decade, activity was limited, but by 1941, the department reorganized. Two years later, a used power and light truck was purchased and, in 1944, the company received additional equipment. Finally the department incorporated in 1948 and in 1950 the fire district was enlarged.

Hard work and a variety of fundraising activities began with street dances, card parties, and bingo games all raising money to purchase land for a new firehouse. Then volunteers began the job of erecting their new firehouse.

In the meantime, Guilderland’s firemen were able to purchase a new Dodge truck and body to finally have a real piece of firefighting equipment. At last, in 1958, the new firehouse was dedicated.

Over the years, additional land has been acquired with the much expanded current firehouse on the site today.

Business

A business district had begun along the old Western Turnpike in the early 1800s, continuing into the 20th century along Route 20. The general store that served several generations in Guilderland operated under several owners over the years, but was best known as Ward’s Store.

The post office was located in Ward’s Store, leading to much foot traffic during the years until a new post office was opened in 1961 on the opposite side of Route 20. At the time the new post office opened, T.B. Ward had been postmaster 46 years.

In 1928, the Tompkins and Hoe garage opened, expanding in 1932 to not only sell and repair cars, but also sell farm equipment under the name Hamilton Garage.

In 1927, the Bohl Brothers began their bus company and erected a large garage to store and maintain buses. The bus business operated there until 1949.

A large frame building on what long ago had been the site of Sloan’s Hotel was home over the years to a gas station, laundromat, luncheonette, a very early home of the Guilderland Library from 1959 to 1961, and the town assessor’s office. Finally, in 1968, a laundromat fire spread, resulting in the building being taken down.

In this section of Route 20 also stood the Guilderland Gift House and the dry cleaners that opened in the 1950s. The old Ward’s Store, ending its days as a costume shop, was taken down for firehouse expansion.

Once Star Plaza and Twenty Mall went up at the far eastern edge of Guilderland, business within the confines of the hamlet slowly disappeared.

Service

Over the years a variety of activities were available for the hamlet’s residents. Early in the 20th century, several women belonged to the Suffrage Club while others were active in the Women’s Christian Temperance Union.

By the 1920s, a Parent Teacher Association had been formed at the elementary school. Men were involved in playing baseball, especially in early years when the Iosco team had a loyal following.

Generations of all ages informally skated on the mill pond once it was frozen. Boy Scout and Girl Scout troops and Sunday schools were available for children.

During both World War I and World War II, community members pitched in with Red Cross volunteers meeting regularly at Temperance Hall to sew articles needed by the troops. Volunteers served as air-raid wardens during World War II.

Many young community members served in these wars. During World War II, an honor roll was erected on the Route 20 corner of the Schoolcraft House, with the permission of the Magill sisters, owners at that time.

During the post-war period, the Guilderland Fire Department played an active role in village life. Women could join the Home Bureau. A few became involved in the early establishment of the Guilderland Library, which for a short time was located in a commercial building on Route 20.

Similar to the experience of other hamlets in the town with the coming of suburbia and population growth, especially with large numbers of outsiders moving in, the Guilderland hamlet was no longer a homey little place where everyone knew everyone and was served by small, locally owned businesses.

In addition, Guilderland faced the challenge of being located on Route 20, the most heavily traveled highway in the town. But in spite of this, the hamlet of Guilderland remains a very nice place to live with its fire department and historic church helping to preserve its individual identity.

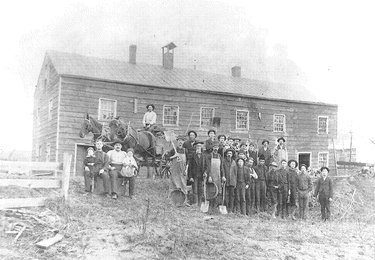

— Photo from the Guilderland Historical Society

Workers at the foundry posed for a photo along with the draft horses that hauled finished iron products to the Fullers West Shore Railroad Station, returning with iron ingots to begin the manufacturing process. Sitting in front of the horses were owners Jay Newberry and George Chapman.

While thousands of drivers now pass through the hamlet of Guilderland daily, four centuries ago wilderness covered the area. Native Americans had worn a trail there leading south from the Pine Bush later followed by German Palatines in 1712 trekking to their new home in Schoharie.

As the 18th Century went on, other settlers followed the same route, settling in areas below the Helderberg escarpment in what is now the town of Guilderland. Within a few years, the trail developed into a dirt road known as the Schoharie Road.

This was the beginning of the hamlet of Guilderland’s history.

In the years prior to the Revolution, almost all of the town’s settlement was in the higher areas to the west, although a few Europeans did establish homes and a mill along the Hunger Kill close to its mouth with the Normans Kill.

Settlement really began in what is now the hamlet of Guilderland when, in 1785, Leonard de Neufville, a Dutch citizen, established a glassworks in the Hunger Kill ravine. Raw materials for glassmaking were readily available at this spot: a plentiful supply of water, sand, and wood for fuel. Window glass and bottles would be produced here with de Neufville hoping the new nation with its growing population building homes and other buildings would provide a growing market.

His father, Jean, and a number of German glassblowers joined him by 1787 in the tiny community they had named Dowesburgh. Conditions were difficult at first. A visitor to the de Neufvilles was appalled to find them living in “a miserable log cabin.” Conditions for the workers couldn’t have been any better.

And, to complicate matters, glass products had to be hauled into Albany via Schoharie Road and King’s Highway until 1800 when the Western Turnpike opened, providing a more direct route.

Improvement in living conditions came in 1796 when planning laid out what is now Hamilton Street and the route of the Schoharie Road shifted a bit to the west to run down Willow Street.

The little community now had the new name of Hamilton chosen to honor President George Washington’s Secretary of the Treasury Alexander Hamilton, a promoter of manufacturing in the new nation. Around this time, there were two taverns established adjacent to the Schoharie Turnpike, one operated by Christopher Batterman, the other by John Schoolcraft.

“Jedediah Morse’s Gazetteer,” published in 1798, remarked that in Hamilton were “two glasshouses and various other buildings with curious hydraulic works to save manual labor by the help of machinery,” calling it, “one of the more decisive efforts of private enterprise in the manufacturing line as yet exhibited in the United States.”

In spite of this favorable review, the glassworks had had financial ups and downs and changed ownership several times.

The Great Western Turnpike was being cut through in 1800 and, although charging tolls, would be an improved and direct connection between Albany and Cherry Valley, an area just being settled.

Once the Turnpike was completed by 1804, heavy traffic was rolling through the tiny community of Hamilton: regularly scheduled stage coaches; carriages; wagons pulled by ox teams; settlers moving west; and drovers bringing cattle, sheep, pigs and turkeys to market in Albany.

Blacksmiths and wheelwrights were needed with one or more established in Hamilton at an early time.

A few years later, the 1813 “Spafford’s Gazetteer” claimed the glassworks had an output of 500,000 feet of window glass annually. There were now 56 mostly small houses in the community.

Within two years however, the glassworks closed down because the plentiful fuel supply had run out in the nearby area and glassblowers and others involved with the glassworks such as Col. Lawrence Schoolcraft and his son, Henry Rowe Schoolcraft, moved on.

Other small-scale manufacturers moved into the ravine at various times during the 19th Century, including factories manufacturing woolen cloth, cotton batting, hats, and eventually an iron foundry.

By 1815, the Batterman and Schoolcraft taverns had operated for many years although it is not known when they closed. George Batterman, another member of the Batterman family, opened up a tavern on the south side of the new turnpike. His tavern was on a sizable piece of land and, to accommodate the animals that were brought along the turnpike, the property included barns, pens, and sheds.

A short distance to the west, Russell Case also opened a tavern although, when traffic was no longer heavy, it reverted to a family farm. Around the outskirts of the community, farms had been established and a member of the Batterman family had dammed the Hunger Kill to establish a grist mill just to the west of the village.

By now, the population had grown to the extent that the United States Postal Service opened a post office in what was then the most populous community in the town of Guilderland, assigning it the name Guilderland. If you’ve ever wondered why the hamlet came to be called Guilderland instead of Hamilton, that’s your answer.

Churches in Hamilton

Back in 1796, when Hamilton and Willow streets were laid out, an octagonal combination church and school building was also constructed. At first, various visiting ministers preached there, although usually it was a Presbyterian minister.

Finally, in 1824, the church formally became part of the Albany Presbytery, calling itself Hamilton Union Presbyterian Church. A Sabbath School was established and weekly prayer services were held.

Originally, the school which shared the building prepared boys for college, but after the 1812 state law setting up common schools, it educated boys and girls through the eighth grade. In 1834, the original octagonal building was removed and in its place a new larger church was erected.

The middle years of the 19th Century brought two other new churches to the community. A small Baptist church was erected in about 1840 on the south side of the turnpike. Within a few years, the Baptists left and a Catholic church took over the building for a short time.

After the Catholics left, the building remained empty until a temperance group called the Good Templars moved in and were active in the community during the later years of the 19th Century. Finally, the Order of Red Men also began to use the building. In later years in the 19th Century, it was usually referred to as Temperance Hall.

Guilderland’s Methodist-Episcopal Church, built on Willow Street in 1852, was the result of the growth of Methodism in Guilderland. A few years later, the church was jacked up and a cellar dug underneath with a parsonage purchased across the street.

It was also in these years that the Hamilton Union Church purchased its first parsonage to the east of the church, then, after a few years, sold it, replacing it by purchasing a home directly in front of the church.

Two grand homes and a grand hotel

The 1840s brought the community the construction of two beautiful homes. One was John Schoolcraft’s Gothic Revival summer home.

Schoolcraft, a local boy who had grown up in the hamlet, moved into Albany where he achieved great success in the business world and became friends with politically influential people. Located on the turnpike opposite Sloan’s Hotel, his new home sat on 10 acres stretching back from the road.

Farther to the east on the turnpike was Rose Hill, built in 1842 by John P. Veeder, which remained in family hands during the remainder of the 19th Century.

When George Batterman died, his tavern was left to his daughter and son-in-law, Henry Sloan, who then ran it until at some point in the 1840s it burned. When Sloan rebuilt, it had become a larger hotel, which became well known for its hospitality, attracting everyone from the governor and wealthy Albanians to ordinary travelers.

The hotel was often the scene of political rallies, both Republican and Democratic, and for donation parties for the Presbyterian minister.

For a time, the area was even called Sloan’s.

Prospect Hill Cemetery opened in 1854, having obtained 50 acres from John P. Veeder. It was one of the then stylish rural cemeteries in fashion at that time.

A decade later, its officials set aside an area of land where Civil War soldiers could be buried in a free plot. As the observance of Memorial Day became an important feature of 19th-Century life, the cemetery became the focal point of local Memorial Day ceremonies and had as many as 5,000 people there for the occasion later in the century.

Willow Street in the hamlet itself was the starting point for the parade to the cemetery.

A look at the small hamlet is provided by the 1866 Beers Map, which shows the Presbyterian, Methodist, and Baptist churches; Swann’s marble yard where gravestones were fashioned; a doctor, Sloan’s Hotel; a mill; a carriage shop; two parsonages; Weavers store; a hat factory; several houses; and a school.

The school had moved to a building on Willow Street separate from the Presbyterian Church in 1843.

As the years passed, the small 1834 Hamilton Union Presbyterian Church needed replacement. Taken down to make room for a new larger church, the new building opened in January 1887. The Meneely bell, which had been purchased in 1865, was rehung in the new steeple.

Foundry booms, then leaves

At some point after the publication of the 1866 map, the hat factory was gone, replaced by an iron foundry run by Wm. Fonda. Ownership then passed to two brothers-in-law, Jay Newberry and George Chapman, who quickly began to expand its capacity with replacement of the original building and the purchase of additional acreage of land.

Immediately successful, the foundry’s draft horses hauled finished iron products out the turnpike to the West Shore Railroad station at Fullers, returning to the foundry with iron ingots for production.

Employment increased steadily with 25 workers in 1886 and twice as many in the 1890s. The population of the hamlet certainly grew and the foundry workers’ wages brought prosperity for the businesses.

Newberry and Chapman seemed to have treated their workers fairly and paid wages on time. Sometimes they provided recreational activities for the men as well. Neither labor unrest nor strikes ever were a problem here.

One night in January 1890, flames erupted at the foundry causing the loss of important buildings, but these were quickly rebuilt. Although a year later George Chapman died at age 31, Jay Newberry continued the business.

However, being so far from a rail line was a definite handicap and Newberry began to look to relocate the foundry. His announcement in 1896 that he was moving the foundry to Goshen, New York to be on a rail line was a shock to the community. The foundry was put up for sale, but it took until 1900 to find a new owner.

By 1890, the school age population had grown to such numbers that a new enlarged schoolhouse was necessary. That September, the teacher and the children used the Red Men’s Hall as a temporary schoolhouse while the old Willow Street schoolhouse was taken down, a new foundation dug, and a new two-room school was erected on the same site.

Later that fall, a second teacher was hired. The new school was opened for students and their two teachers in January 1891 when they returned from Christmas vacation. Opinion in the little community was that their new school “is the best in the county outside the cities.”

As the years of the 19th-Century came to a close what had been a prosperous rural community was faced with uncertainty. Many residents had to choose whether to leave in search of other employment, or stay in their familiar surroundings while, in many cases, extended family members relocated to Goshen.

The question of what would become of the site of the foundry must be determined.

Next month, we will follow the second part of the story of the hamlet of Guilderland with its transition into the automobile age and suburbia.

— Photo from the Guilderland Historical Society

This cottage was once the residence of the toll-taker at Toll Gate Number 5 on the Plank Road. There would have been a gate across the road, which he opened for travelers once they paid their toll ranging from one-and-a-half cents to 28 cents depending on what was passing through. At night, the gate was locked. Certain times, a person went free: jury duty, church attendance, muster duty, going for a physician or going to the grist mill or blacksmith. This cottage was located on Route 146 near the town’s Winter Sports area, but on the opposite side of the road, taken down in the last decades of the 20th Century.

Navigating Route 146 from the Route 20-Hartman Corners intersection to Altamont takes minutes, depending on traffic. You are the latest of the peoples who have traveled in the same direction.

In centuries past, Native Americans threading their way through the wilderness that once covered the area created a network of trails. Their trails did not follow the shortest distance between points, but meandered along waterways avoiding difficult or swampy areas, choosing the easiest spot to ford streams.

When in 1712 German Palatines, refugees escaping war and religious persecution in their Rhineland home, traveled from Albany to Schoharie where the British allowed them to settle, they left Albany on the King’s Highway, once a trail through the Pine Bush.

At one of the taverns, most likely the Verraberg Tavern, they began to follow another trail leading in the direction of Schoharie. Entering what is now Guilderland, the trail followed a small stream that ran just to the east of what is now Hamilton Union Presbyterian Church until it reached the Hungerkill. These are among the first Europeans to pass through Guilderland.

“A Brief Sketch of the First Settlement of the County of Schoharie by the Germans,” written by Judge John M. Brown in 1823, based on accounts he had collected from older residents, was the first information in print regarding this route.

He wrote that, in the year 1712, “there were no other roads to Schoharie, but five Indian footpaths … the second, beginning at Albany, led over the Helleberg … to Schoharie at Foxendorf. This was the trail which the settlers traveled when they moved into Schoharie … On this route with very little variation later went the first Schoharie Road to Albany.”

Once the Palatines crossed the Hungerkill, they veered off to the right across the present golf course and Route 146 in the vicinity of Tawasentha Park. Swinging to the south they went down to the flats along the Normanskill where the trail forded the creek.

They continued around and over the hill coming out near the top and went through what is now Guilderland Center on as far as Osborn Corners, picking up Weaver Road and at the end continuing straight into Altamont and on up the escarpment through Knox and Berne to Schoharie.

Of course, this was all wilderness in 1712, but using modern names gives the idea of the route they followed.

Early documentation includes maps drawn by Captain William Gray for George Washington of “Road from Albany to Schoharie” and “Albany to Man’s Mill,” a location on Schoharie Creek. Indicating the meeting house, probably the log prayer house of the Helderberg Reformed Church, the maps show a road similar to Weaver Road.

This route was followed by the later settlers as people moved into Guilderland and beyond and became known as the Schoharie Road, the main road during most of the 18th Century.

A notice relating to a piece of Guilderland real estate in the Albany Register of July 14, 1812 reads, “… being in the Town of Guilderland, in the County of Albany, beginning at the southwest corner of the farm of Nicholas Van Patten and runs thence westerly along the Schoharie Road one hundred and sixty-three feet ….”

This shows that the road, called the Schoharie Road, was down on the flats near the Normanskill, which is near the end of modern-day Vosburgh Road. The location of the Van Patten farm is on the 1767 map of the West Manor of Rensselaerwyck.

If you have ever wondered why the Tories were hiding in and around the Van Patten barn in what seems like a very out-of-the-way spot at the time of the Battle of the Normanskill, his farm was on the road out of town and they were on their way to aid General John Burgoyne.

The Schoharie Road was a circuitous route, time-consuming in the later 18th-Century when farmers began shipping farm products to the Albany market when time on the road became an important factor.

When a more direct route across the Normanskill and up the hill evolved isn’t known, but a bridge across the Normanskill at the spot probably similar to the site of the current bridge can be documented.

In 1804, the second year of Guilderland’s town government, the town’s three road commissioners noted “the sum of Twenty-Three dollars which they have expended on the Bridge across the Normanskill at John Bankers ….”

The Bancker family had settled a farm along the Normanskill prior to 1734 and there is a New York State Historic Marker at the location along Route 146 today. The name became anglicized to Banker and successive bridges over the Normanskill and the hill beyond were informally called Banker Bridge and Banker Hill, later corrupted to Bunker Bridge and Hill, well into the 20th Century.

But, in 1804 did a road continue on up the hill as it does today? It’s probable a simple dirt road went to the top.

Plank Road

In 1849, the Schoharie-Albany Plank Road was chartered. Investors, including several Guilderland men, decided that it would be profitable to construct a turnpike made of planks laid over parallel wooden runners connecting the Great Western Turnpike with Schoharie.

In an era of cheap, plentiful wood, plank roads had become popular, offering a smoother ride than a dirt turnpike. For the convenience, travelers would pay tolls. With Toll Gate Number 5 located on Banker Hill, obviously the plank road followed the shortest way up the hill. The Schoharie Road fell into disuse except for a few local farmers.

Once cresting the hill, the Plank Road followed the route of the Schoharie Road into Guilderland Center. Note as you are approaching the overpass today that there is a New York State Historic Marker at Wagner Road, which veers off. That is the original route into Guilderland Center and the current overpass was placed to the north.

After passing through Guilderland Center, the Plank Road went up to Osborn Corners, picking up Weaver Road and then on into Altamont where it veered right on what is now Schoharie Plank Road. The Plank Road then went on up the escarpment similar to Route 146 today, and on to Knox and Schoharie. Toll Gate Number 4 was part way between Weaver Road and Altamont.

At first successful with a regular stagecoach running between Albany and Schoharie and much farm traffic, the Plank Road in time, had its planks rot. They became increasingly expensive to replace, causing profits to decline.

The finishing blow came in 1863 with the opening of the Albany & Susquehanna Railroad between Albany and Schoharie. The Plank Road was almost immediately out of business, but the route it followed continued to be the route used for local traffic into the 20th Century.

Once the automobiles came chugging along this very poor road, they were facing a challenge with poor road surface and some nasty turns, including the one onto what is now Weaver Road at its upper end.

Early in the 20th Century, New York state stepped in to do some simple upkeep on the main highways. In 1907, an irate Guilderland Center resident complained in The Enterprise about an automobile traveling through the village “at a velocity of speed that would put a western cyclone to blush, giving people on their way to church a good bath of state-road grit.”

In addition to curves, there was the dangerous grade-level railroad crossing in Guilderland Center where two area men were killed in the early 1920s when they pulled in front of an oncoming train. This problem was solved in 1927 when the overpass was built slightly to the north of the original crossing.

Pavement

Finally, in May 1929, the news appeared on page one of The Enterprise announcing “State Plans For New Altamont-Hartmans Road” to be 20 feet wide of reinforced concrete. It would run straight instead of following Weaver Road with a new bridge built over the Black Creek.

The Banker Bridge would be replaced with a steel and concrete structure with a 155-foot span and width between the curbs of 30 feet. There would be a new intersection with Hartmans Corners, which would curve around coming out to the turnpike just west of the Case homestead, years later the site of the M&M Motel. This was supposed to replace a sharp turn and poor visibility.

A few months later, in October 1929, a notice appeared requesting bids for highway improvement for the highway leading out of Altamont east through Guilderland Center to Hartman’s Corners on the Cherry Valley Turnpike.

“This highway has needed reconstruction for some time and the improvement will be welcomed by the traveling public,” the notice said.

Of the 17 bids for construction that were submitted, Lane Construction Corp. of Connecticut would be doing the work. Its winning bid for this stretch of road was $264,132.40.

Within a week, the New York State Department of Transportation was surveying to locate the new highway, eliminating the turn off Weaver Road, running the road straight down “Church Hill.” The name dates back to the 19th Century when St. James Lutheran Church was once located at the top of Weaver Road.

In addition, other sharp curves were to be eliminated including the one at Osborn Corners where the road swung in front of the one-room school. The road, instead, would go straight behind the rear of the school.

April 1930 brought construction crews to town. Their first job was to clear trees along where the road would be widened.

By June, the construction company had begun laying cement and was expected to reach the railroad bridge in Guilderland Center within the week. Two weeks later, all concrete had been put down between Altamont and work would soon begin on the steelwork on the new Bunker Bridge.

Finally, the Aug. 29 Enterprise announced the opening of the “new concrete highway that is one of the finest pieces of engineering to be seen in this part of the country. One may now drive from Altamont to Guilderland in less than 15 minutes, over road as smooth as a parlor floor.”

If ever you are driving Route 146 at a low-traffic time, recall that before you Native Americans hunting or trading, desperate Huguenots trudging to Schoharie, early settlers establishing farms, Patriots and Tories at war with each other, a clattering stage coach carrying passengers, early motorists racing through at 15 or 20 miles per hour all were here before you, and in a few spots over exactly the same stretch of road.

Realize that even this mundane strip of highway has a long and rich history.

In the Town Historian’s mail recently was a photograph of G. S. Vroman’s Altamont Livery Stable, sent by the Madrid, New York Town Historian. She had come into possession of what was obviously a professional photograph mounted on embossed cardboard as part of a donation of Madrid area photographs.

Madrid is northwest of Potsdam and is not far from the St. Lawrence River. How an Altamont photograph ended up in Madrid has been a mystery.

The date 1900 is visible on a hanging sign high on the front of the stable. Posed below is a pair of two horse teams, each harnessed to a rig designed to carry passengers, each with a smart looking driver. The man standing between the two was most likely G. S. Vroman himself.

This photograph brought to mind that 1900 was still part of the horse-drawn age, a time when many local men were employed at various occupations relating to horses. Although most men were engaged in farming, a sizable employment group would have been horse-related, men who were blacksmiths, harness makers, wheelwrights, wagon and carriage makers, and even carriage painters. Some also farmed part-time, while others worked full-time at their trade.

In 1958, the late Town Historian Arthur Gregg had the opportunity to review a ledger kept in the 1840s by John H. Gardner whose farm was outside Altamont on the outer edge of Meadowdale. He eventually became one of Guilderland’s most affluent farmers and businessmen. But, in the early 1840s, he began by doing blacksmith work, not only shoeing horses, but at that earlier time shoeing the oxen that were still to be found on Guilderland’s farms.

Oxen would have been a common work animal during the town’s very early years. Oxen were inexpensive, castrated bull calves that became docile beasts of burden trained in pairs. Sturdy and capable of laboring long hours at heavy work, they were not prone to disease and, after their work years were over, they could be roasted and eaten.

Oxen were superior to horses when working in recently cleared fields with snags and stumps and were less likely to get injured. At work, they were bound together with a wooden yoke, attached by a curved bow that went under their necks to keep the yoke over their shoulders. Also requiring shoes, because their hooves were different from those of horses, oxen required two separate metal pieces for each hoof.

That oxen continued to be used on area farms in Guilderland in the 1840s was illustrated by entries in Gardner’s ledger. He sold Adam Blessing a neck yoke for $2, repaired John O. Truax’s team’s neck yoke for 25 cents, and sold ox bows to James Westfall for 50 cents.

A very few oxen were still around town in the late 19th century. In an 1889 Enterprise ad, an Altamont man offered a 3,000-pound pair for sale or would trade for a horse, while at the 1892 Walter Church auction at the Kushaqua, a pair was on offer.

Horse-related occupations

An 1870 directory of Guilderland residents listed not only individual names of male residents but also their occupations. At that time, farming was the activity of almost all men in Guilderland, but 17 men with horse-related occupations were identified.

Six were blacksmiths with one who was listed as a farrier, a man who only dealt with the care and shoeing of horses’ hooves. On the other hand, blacksmiths spent most of their time shoeing horses, but were also capable of repairing or fabricating iron products.

Henry Burden of Troy, beginning in the 1840s, developed a method to manufacture horse shoes by machine, making the lives of blacksmiths much easier because they no longer had to fabricate each horse shoe before shoeing the horse.

Also in Guilderland in 1870, one man made harnesses, while six were described as wagon makers, and a few of these did blacksmithing in addition. Rather surprisingly, three men claimed they were carriage painters, but may have done other types of painting in addition.

One Guilderland Center man was listed as “mail and stage proprietor from Guilderland Center to Albany.”

Once The Enterprise began publishing in 1884, blacksmiths occasionally advertised either their services or their shops for sale if they wished to move on.

In 1885, G.A. Lauer of Guilderland Station (renamed Meadowdale) let the public know he could provide the services of a blacksmith, wheelwright, and repairs. In addition, he informed folks of his “particular attention paid to interfering, overreaching and lame horses.”

One blacksmith who wanted to move on advertised in1884: “To Rent: A blacksmith shop at Fullers Station. Possession given April 1st. For particulars enquire Leroy Main, Fullers Station, NY.”

That a blacksmith was important to a community at that time was the comment in a later 1890 Fullers column: “A good blacksmith is wanted in this place.” Guilderland Center was more fortunate having Charles Brust’s blacksmith shop in business for decades, already listed in the 1870 directory.

A horse couldn’t pull a wagon, carriage, or plow unless harnessed. A few men made and repaired harnesses. In 1888, two local harness makers were in operation, one in Altamont and the other in Guilderland Center.

C.V. Beebe was in a fixture in Altamont for many years. In 1900, he advertised that he was a “manufacturer and dealer in harness, blankets, robes, whips and a general line of horse furnishing goods.”

“Laborer” was a category not mentioned in the 1870 directory, but in the listings of an 1888 directory, there were many of them. Quite a number seemed to have been helpers in various horse-related occupations in Guilderland. “In 1890 Walter Stocker is employed by Mr. James Keenholts to look after the management of his livery stable,” as would have been the men driving G.O. Vroman’s rigs.

1900’s Uber

Livery stables came later to Guilderland’s horse-drawn scene. The taxi service or Uber of its day, a livery stable needed enough customers demanding the service to pay for the investment in horses and rigs.

Once Altamont had a railroad depot where regularly scheduled local and long-distance D&H trains stopped and the village with its growing population had become a summer destination with its hotels and summer cottages, a livery stable could be a profitable operation.

No one was listed as operating a livery stable in the 1870 Guilderland directory, but the town had grown so that by the time Howell & Tenney’s History of Albany County was published in 1886, Ira Fairlee was mentioned as Altamont’s livery stable proprietor. His name also appeared in the 1888 directory.

By 1900, Altamont had multiple livery stables, the earliest one located on Prospect Terrace in the area of today’s Altamont County Values Store, possibly the same building as listed for Ira Fairlee.

The owner preceding G.O. Vroman was Dayton Whipple who was in business as early as 1892. His livery operation was once described in The Enterprise as “well appointed” with “fashionable carriages, buggies, two, three and four seated rigs.” In addition, he employed “careful, reliant, intelligent drivers.”

These men would meet trains or would have a scheduled run to a tourist destination such as the Thompson’s Lake hotels. Another regular run was to meet the D&H train on weekends when it stopped at Meadowdale to see if there might be possible passengers who wanted to be taken to the top of the Helderberg escarpment.

Change came quickly with the coming of the automobile. At first, livery owners added one or two autos to their offerings. In 1913, John Becker added a five-passenger touring car to his livery service and others had to follow his example.

Once ownership of an automobile became common, the days of the livery stable came to an end. The horse-drawn occupation that hung on the longest was that of blacksmith because many people continued to own horses even after they finally got their own automobile.

To this day, some Guilderland residents own horses, but it is the farrier who now comes to them with a specially equipped truck.

Mystery solved

In attempting to find additional information in The Enterprise regarding Dayton Whipple, your Town Historian stumbled on this bit of news in the May 9, 1913 Village and Town column: “The following, clipped from the Madrid Herald of April, 1913 will be read with interest by many Altamont friends.

“Undertaker Fay G. Mann has purchased a beautiful new eight column (I suspect this was meant to be eight seater) Moscow top funeral car which gives him equipment second to none in this section. The car is fitted with inch and one-eighth inch hard rubber tires and white and black interchangeable curtains, the outfit complete costing $ 1,000.”

Mr. Mann was formerly a resident of this village and is a brother-in-law of Mr. Geo. S. Vroman. Mystery solved!

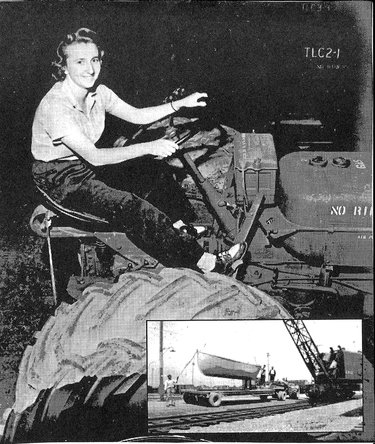

— Photo from Mary Ellen Johnson

Ella Van Eck shared information with Mary Ellen Johnson years ago about her experiences working at the depot as a young woman during World War II. She drove heavy equipment and was one of the people chosen to go to Washington, D.C for the bond rally featuring the local depot. The insert photo shows a lifeboat being loaded on a trailer used to transfer the boat to a freight car with her on the tractor to tow it.

This is the first of a two-part series on the Army depot in Guilderland Center, site of the current Northeastern Industrial Park.

With the nation at war as 1942 began, security was tightened at the Army depot. Information about operations were released only when officials chose.

Armed guards patrolled the fenced perimeter on horseback while guards with 16 trained dogs covered warehouses and the grounds. Security clearance and fingerprinting was necessary for all employees. Aircraft were forbidden to fly over the facility.

Increasing traffic tie-ups in Guilderland Center brought a traffic light at the intersection of Route 146 and what is now School Road leading to the only entrance to the depot.

The devastating destruction resulting from bombing raids by German and Japanese air forces led to nighttime blackouts. The first of these in this area was announced ahead of time for Jan. 16. When sirens sounded, everything was to be darkened and the master switches would be pulled at the depot; work would stop until the all clear.

Catastrophe hit at the end of that first month of operation when fire blazed in the administration office building. While the wooden two-story building was leveled, there were no casualties. Lost were project records, supplies, and office equipment.

Flames shooting up 100 feet in the air were fought by the depot fire department with Altamont, Guilderland Center, and Voorheesville volunteer fire departments called in to assist. A huge number of spectators gathered to watch outside perimeter fences. No cause was ever determined.

WPA helps

Although the buildings were in operation, the grounds had not been completed. Works Progress Administration workers were approved to construct roads, sewers, parking areas, sidewalks, gutters, and water lines and do some basic landscaping.

The WPA was a New Deal project to provide paying jobs for the unemployed and the lieutenant colonel had gotten approval to bring them in for the completion of the project. At this time, the depot was renamed the Voorheesville Holding and Reconsignment Point in place of Voorheesville Regulating Station.

That June, a formal ceremony was held to honor flags of nations united against the Axis powers and to mark the official completion of the project, which by then was estimated to have cost $10 million dollars.

Designated as a clearing house for lend-lease materials, the project had provided work for thousands. The construction workers were gone, but white-collar employees were carrying out administrative duties.

Now others would begin the work of arrival and shipment of war materiel since the WPA workers had finished the details. Unusually, the Voorheesville Holding and Reconsignment Point was open to the public at the event that day.

Worn tires, bad road

The Sentinel was a depot employee newspaper, which made a forceful complaint about the condition of the road from Guilderland Center leading to Depot Road (now School Road). Most employees had to travel its length to get the entrance to the depot. It was in wretched condition.

In the meantime, purchase of new tires for passenger cars had ended in 1941 and by now driving old worn tires over a bad road twice daily was a trial. Cars themselves were wearing down and workers were complaining that the condition of the road was becoming worse even after having been turned over to Albany County in 1943.

“All that has happened is more holes and a rougher road,” The Sentinel reported.

The road from Voorheesville to the entrance of the depot was improved late in 1942 and had been extended out through the Wormer and Clikeman farms to meet Route 146. It has been said that what is now called Depot Road was a concrete road designed to accommodate tanks being driven over from the Alco Plant in Schenectady where they were manufactured.

Long hours

What was it like to have been an employee during World War II?

Many years ago, Ella Van Eck reminisced to me about her days driving heavy equipment at the depot. Fortunately, I took notes. She earned $1,320 annually or 78 cents hourly.

Many women as well as men were employed at the depot and she remembered a few Black workers as well. Knowing racial treatment in the 1940s, it is likely they were doing custodial or kitchen work.

The depot was under the direction of a commanding officer with the rank of colonel and two majors, one in charge of heating and plumbing and the other in charge of movement operations.

When this young woman was first hired, she was assigned as a chauffeur/mechanic with the responsibility to drive officers in an open jeep, a freezing job in winter.

Later, Van Eck became a crew member of a team unloading military supplies as they came into the depot and then reloading supplies to be shipped out, everything from jeeps and lifeboats to dried rations and army cots.

Each of these crews, many of whom were women, had a forklift driver, a checker who was an inspector, plus a foreman and four others. Men did the heavy work, women drove forklifts or were checkers.

During the course of the war, there was one fatality when a man was crushed by a crate, pinning him against a freight car.

Starting time was at 7 or 8 a.m. depending on daylight with the cafeteria opening at 6 a.m. The food served in the cafeteria was considered “good.”

The cafeteria tables often did double duty when huge shipments of materials had to be sent out in a hurry. Employees often worked around the clock or worked three weeks straight with no days off.