Depot workers shipping supplies from the home front made victory in World War II possible

— Photo from Mary Ellen Johnson

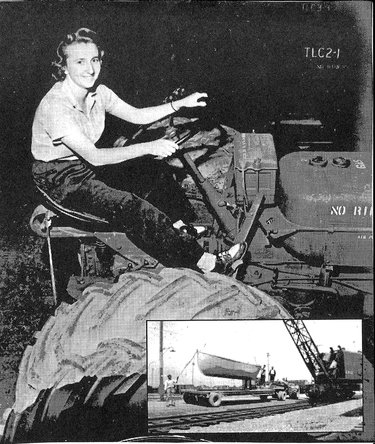

Ella Van Eck shared information with Mary Ellen Johnson years ago about her experiences working at the depot as a young woman during World War II. She drove heavy equipment and was one of the people chosen to go to Washington, D.C for the bond rally featuring the local depot. The insert photo shows a lifeboat being loaded on a trailer used to transfer the boat to a freight car with her on the tractor to tow it.

This is the first of a two-part series on the Army depot in Guilderland Center, site of the current Northeastern Industrial Park.

With the nation at war as 1942 began, security was tightened at the Army depot. Information about operations were released only when officials chose.

Armed guards patrolled the fenced perimeter on horseback while guards with 16 trained dogs covered warehouses and the grounds. Security clearance and fingerprinting was necessary for all employees. Aircraft were forbidden to fly over the facility.

Increasing traffic tie-ups in Guilderland Center brought a traffic light at the intersection of Route 146 and what is now School Road leading to the only entrance to the depot.

The devastating destruction resulting from bombing raids by German and Japanese air forces led to nighttime blackouts. The first of these in this area was announced ahead of time for Jan. 16. When sirens sounded, everything was to be darkened and the master switches would be pulled at the depot; work would stop until the all clear.

Catastrophe hit at the end of that first month of operation when fire blazed in the administration office building. While the wooden two-story building was leveled, there were no casualties. Lost were project records, supplies, and office equipment.

Flames shooting up 100 feet in the air were fought by the depot fire department with Altamont, Guilderland Center, and Voorheesville volunteer fire departments called in to assist. A huge number of spectators gathered to watch outside perimeter fences. No cause was ever determined.

WPA helps

Although the buildings were in operation, the grounds had not been completed. Works Progress Administration workers were approved to construct roads, sewers, parking areas, sidewalks, gutters, and water lines and do some basic landscaping.

The WPA was a New Deal project to provide paying jobs for the unemployed and the lieutenant colonel had gotten approval to bring them in for the completion of the project. At this time, the depot was renamed the Voorheesville Holding and Reconsignment Point in place of Voorheesville Regulating Station.

That June, a formal ceremony was held to honor flags of nations united against the Axis powers and to mark the official completion of the project, which by then was estimated to have cost $10 million dollars.

Designated as a clearing house for lend-lease materials, the project had provided work for thousands. The construction workers were gone, but white-collar employees were carrying out administrative duties.

Now others would begin the work of arrival and shipment of war materiel since the WPA workers had finished the details. Unusually, the Voorheesville Holding and Reconsignment Point was open to the public at the event that day.

Worn tires, bad road

The Sentinel was a depot employee newspaper, which made a forceful complaint about the condition of the road from Guilderland Center leading to Depot Road (now School Road). Most employees had to travel its length to get the entrance to the depot. It was in wretched condition.

In the meantime, purchase of new tires for passenger cars had ended in 1941 and by now driving old worn tires over a bad road twice daily was a trial. Cars themselves were wearing down and workers were complaining that the condition of the road was becoming worse even after having been turned over to Albany County in 1943.

“All that has happened is more holes and a rougher road,” The Sentinel reported.

The road from Voorheesville to the entrance of the depot was improved late in 1942 and had been extended out through the Wormer and Clikeman farms to meet Route 146. It has been said that what is now called Depot Road was a concrete road designed to accommodate tanks being driven over from the Alco Plant in Schenectady where they were manufactured.

Long hours

What was it like to have been an employee during World War II?

Many years ago, Ella Van Eck reminisced to me about her days driving heavy equipment at the depot. Fortunately, I took notes. She earned $1,320 annually or 78 cents hourly.

Many women as well as men were employed at the depot and she remembered a few Black workers as well. Knowing racial treatment in the 1940s, it is likely they were doing custodial or kitchen work.

The depot was under the direction of a commanding officer with the rank of colonel and two majors, one in charge of heating and plumbing and the other in charge of movement operations.

When this young woman was first hired, she was assigned as a chauffeur/mechanic with the responsibility to drive officers in an open jeep, a freezing job in winter.

Later, Van Eck became a crew member of a team unloading military supplies as they came into the depot and then reloading supplies to be shipped out, everything from jeeps and lifeboats to dried rations and army cots.

Each of these crews, many of whom were women, had a forklift driver, a checker who was an inspector, plus a foreman and four others. Men did the heavy work, women drove forklifts or were checkers.

During the course of the war, there was one fatality when a man was crushed by a crate, pinning him against a freight car.

Starting time was at 7 or 8 a.m. depending on daylight with the cafeteria opening at 6 a.m. The food served in the cafeteria was considered “good.”

The cafeteria tables often did double duty when huge shipments of materials had to be sent out in a hurry. Employees often worked around the clock or worked three weeks straight with no days off.

Exhausted personnel often crashed on top of the tables to catch a brief rest before heading back to their duties. Whenever there was a blackout, work came to a full stop.

Many times, depot workers briefly put aside their work to stand on the side of Warehouse 3 waving to a passing troop train loaded with soldiers who were on their way to be shipped out to combat, knowing sadly that some of these men would never return.

In 1943 and 1944 for about six months, German prisoners of war were housed near the main gate on Depot Road. Each day, they were brought into the cafeteria for meals where a special area was set aside for them.

Depot employees were instructed that under no circumstances were they to communicate with them.

Devotion to duty

Public relations were important. In April 1943, Associated Press ran a lengthy news report, “Much Lend-Lease Material Handled By Army Station,” which appeared in the Albany Times-Union.

Updated information describing the workings of the depot was designed to encourage the folks that needed supplies to know they were rapidly shipped out to the boys overseas. Reconsignment depots such as the Voorheesville Point eliminated tie-ups in getting the needed materials to their destinations.

Arriving at the depot by rail were military supplies coming from manufacturers. As soon as a merchant ship was in port, the supplies were reconsigned for transport. This meant a rapid turnaround for a ship that had just pulled into port, soon fully reloaded and leaving for a new destination overseas.

Large numbers of tanks of various types were stored at the depot but normally only lend-lease material was handled.

Also in April 1943, Colonel Chambliss commended workers for devotion to duty and low absenteeism with workers there handling freight quickly and efficiently. In particular, he complimented workers who had designed a turntable for tanks, which saved much time.

The Voorheesville Point was operating so successfully that operations were studied by both military and civilian representatives from all over the eastern part of the country.

As the war continued, rationing and shortages made driving a challenge, especially with obtaining gasoline and keeping tires road worthy. The depot urged carpooling and set up an incentive system to encourage it.

Riders were urged to buy coupons at a booth in the depot office, then turn them over to car owners who drove them to work. In turn, drivers could turn in the coupons for cash.

Buying savings bonds was considered a duty to help finance the war. Periodically the government would promote a big bond drive.

September 1943 brought great excitement to depot employees because the Voorheesville Holding and Reconsignment Point was to be featured in Washington, D.C. as a part of a “Back the Attack” bond drive exhibit.

The center of attention was to be a 52-by-20-foot scale model of the entire depot complete with miniature buildings, railroad tracks, equipment and rolling railroad stock, really the ultimate model train layout. It was to have a practical purpose upon its return from Washington when it would be used to train new personnel regarding the locations and traffic flow of the depot.

In addition, some of the depot employees from the regular working staff including three women who handled fork lifts were to go along to demonstrate their skills for the anticipated crowds.

A few weeks later, the Times-Union headline “Voorheesville Depot Marks Bond Triumph” told of the patriotism of depot workers who were celebrating buying twice the number of bonds as the original goal for a total of $55,000.

Work stopped for a time for employees to come together with the commanding officer, Colonel Chambliss. He not only complimented the workers but also honored the memory of John Lyngard who had been killed in North Africa by presenting his Purple Heart to his father, Alexis Lyngard, a depot carpenter who had three other sons on active duty.

These depot workers not only were dealing with shortages and hard work, but lived day to day in fear of hearing bad news about a loved one or friend overseas. However, making the best out of a brief break in the work, all during this ceremony an ox was being roasted on depot grounds with vegetables from the Victory Garden there for an employee meal after the program.

Obviously, an effort was made to keep the morale of depot workers up all the while great demands were being made on them to be very productive. “Civilian Help Acclaimed At Army Plants” was another Times-Union headline, giving details of awards made at both the Watervliet Arsenal and the Voorheesville depot.

Six-hundred-and-fifty-three workers were awarded civilian service bars with a limited number of employees chosen to represent all the others. Music was provided by the Depot Band.

As 1943 ended, the five divisions of workers were consolidated into two. Operations were streamlined with a 10-percent reduction in the number of employees.

Yet, by September 1944, it was announced the depot was in need of part-time workers, men of any age to help battle bottlenecks in unloading and loading freight cars. The pay rate was 74 cents hourly with three night’s work from 6:30 to 11:30 p.m. plus Saturday and Sunday for those who could manage it.

Autumn of 1944 saw the Allies making strides in pushing back the Germans and Japanese, but the war dragged on. Draft quotas were up and local newspapers carried notices of local men’s deaths in combat.

December began with snowfall, continuing on into January 1945. Drifts and howling winds closed secondary roads; combined with plummeting temperatures and a gasoline and coal shortage, there was much suffering. Depot workers must have been fatigued.

Finally the end came with Germany’s surrender in April and Japan’s in August. Operations at the depot must have wound down fairly quickly, but the Army facility remained active until the 1960s. The war was not only won by our troops overseas, but it would not have happened without the support of civilians like these depot workers.