— Photo from the Guilderland Historical Society

This old postcard view shows the original grade-level crossing at Guilderland Center. The huge building on the right was the Hurst Feed Mill, which burned before it could be moved to make way for the 1927 overpass. On the left side of the road was a small West Shore station and the large building beyond was a hotel, which burned shortly after the empty feed mill. Today, this original road is a short dead end stopping at the tracks called Wagner Road. It branches off from Route 146 as you approach Guilderland Center.

At the Guilderland Center crossing, West Shore Railroad workers came on the run when the sound of an approaching pair of coupled locomotives was followed by a loud crash. Confronted by a horrific scene, the men looked 50 feet down the track to see, crushed in front of the now-halted locomotives, the remains of a demolished Dodge automobile, its engine hurled into a neighboring field.

Two men ejected by the impact lay crumpled near the tracks, one dead at the scene, the other so critically injured that he died five hours later at Albany Hospital.

Earlier that August 1919 Friday morning, the two men, Hartford Steam Boiler Insurance Co. employees, had been assigned to inspect boilers in Altamont, but tragically later that day the two had become statistics in the ever-increasing toll of grade crossing train-car collision fatalities.

In 1914, records show 199 people lost their lives at New York grade crossings; a year later, the fatality rate increased by 50 percent. By 1927, there were 668 fatalities during the first four months alone. With the explosive increase in automobile ownership, fatalities at grade crossings had become a major safety issue.

PSC intervenes

The recently formed New York State Public Service Commission quickly stepped in, insisting that construction of underpass or overpass crossings should replace grade-level railroad crossings and promised to make railroads pay for a good portion of the work.

Even if local residents were dead set against a crossing proposal, the Public Service Commission had the power to overrule them.

In our area, the initial focus was on the busiest D & H railroad crossings in Bethlehem and New Scotland, but by 1919 Guilderland had also caught the attention of the Public Service Commission. Ironically, earlier on the very day of the Guilderland Center double fatality, officials had been there photographing that very dangerous crossing, the site of other fatalities.

Crossing railroad tracks in those days was a challenging proposition for drivers whose noisy cars made it difficult to hear approaching trains, while their sight lines were often obstructed by buildings, brush and trees, or a curve in the tracks. Rarely were there gates, at that time requiring a railroad employee to operate them.

In Guilderland, only Altamont’s D & H railroad crossing had a part-time gatekeeper. Otherwise, drivers were on their own to stop, look, and listen.

A July 1925 Public Service Commission legal notice in The Enterprise notified residents that public safety required that the crossing at Guilderland Center be replaced with an overhead bridge to the north of the grade-level crossing.

At Fullers, the Western Turnpike (Route 20) would be carried underneath the track at the same site as the current grade crossing. There was to be a public hearing but, if there were any opposition, it would be overruled.

The Guilderland Center plan rerouting the road entering the village 175 feet to the north necessitated removal of Hurst’s Feed Mill. Before construction began, Hurst’s empty feed mill, recently purchased by a new owner who planned to move the building, burned before it could be relocated to make way for the overpass.

The cost of the overpass was estimated to be $120,000, half of it to be paid for by the New York Central Railroad Company, owner of the West Shore Railroad.

Work on the Guilderland Center project took place in the spring and summer of 1927. Artificial hills or inclines had to be built as approaches to the new overhead bridge and by midsummer the project was completed allowing traffic to move over it. The original road (now Wagner Road) dead ended as it approached the tracks.

Two lesser overhead bridges carrying roads over the West Shore tracks were also put in place at the same time, one over the tracks carrying the road to Frenchs Hollow (now Frenchs Mills Road), the other at McCormicks unpaved dirt road (now West Old State Road). Note that in the 1920s most local roads did not yet have officially designated names.

Countryside changed

Fullers’ situation physically disrupted that small community. The writer of a 1926 article pointed out the year before construction began, “The entire character of the countryside is to be changed.”

Being that the West Shore Railroad was a division of the New York Central Railroad, management made the decision that, as long as the Public Service Commission was forcing them to construct an above-ground crossing over Route 20, this would be a good time to bring this branch line up to main-line standards to speed up the movement of freight traffic.

Heading southbound toward Guilderland Center, freight trains approaching the trestle over the Normanskill at Frenchs Hollow had to climb a steep gradient. By the 1920s, freight trains had become longer and heavier, requiring a very slow climb to reach the level of the Normanskill trestle.

Therefore the plan was to lower the approach gradient by creating a long artificial incline to raise the track approaching this trestle gradually. Instead of a short steep climb to this trestle, the long approach would allow locomotives to keep up speed.

This would result in faster freight service on the West Shore, but at the same time artificial construction of a high dirt berm to carry the southbound track created a barrier that would now physically divide the hamlet of Fullers. Instead of the former grade-level crossing, the tracks would now cross Route 20 on two trestles, the higher one carrying the southbound track. Unfortunately the August 1926 Enterprise article detailing the Fullers proposal is extremely blurry, making the exact statistics of the gradients illegible.

In 1926, the contract for all four of these projects was awarded to the Walsh Construction Company, an experienced contractor who had worked on similar projects in surrounding areas. In preparation, they sent in surveyors and arranged for equipment such as steam shovels to be ready to work by April 1, 1927.

Houses were purchased or possibly built on both sites to be used as offices for project foremen. Charlie Quackenbush’s farm was rented as the location for their “camp” where their laborers would live while construction was underway. When the projects were completed, the houses were each later sold to local men.

In the meantime, the New York Central Railroad bought a farm in Guilderland Center adjacent to the railroad tracks just north of the bridge project there to be used as a gravel pit. It was necessary to acquire additional farmland in Fullers because of the extent of their project creating the huge incline and erecting the crossing trestles.

Early in April 1927, actual work began. Walsh brought in a crew of laborers, setting up the camp with Mr. and Mrs. John Mullaney doing the cooking and managing the camp. The type of worker housing is unknown, but establishing these camps at work sites seemed to be their standard practice, mentioned in relation to Walsh projects in the town of Bethlehem.

Andrew Wyatt, a Walsh employee, was in charge of 30 mules pastured on the Quackenbush farm, probably used in hauling wagon loads of dirt as the turnpike was dug out under the tracks. At dawn one morning, all 30 managed to take a jaunt out of the pasture, parading down the turnpike before being rounded up.

The Fullers project was more involved than the Guilderland Center overpass. First, a wooden trestle over the entire stretch of gradient was constructed, reportedly using timber from trees cut while clearing land for Albany Air Port.

Trains hauled in carloads of gravel dug on the Guilderland Center farm over tracks laid on the temporary trestle, dumping their loads on the wooden framework that was left in place and eventually rotted away. Work went on day and part of the night using electric light.

By July 1, the major project was complete, except for concrete work. Two trestles crossed above Route 20, one above the other while the road dipped down underneath.

Some sources have stated the higher of the two trestles was constructed at a later date, but this is inaccurate. A photograph appearing in the April 17, 1927 Knickerbocker News showed the construction project underway with both trestles in place.

Not only was Fullers transformed by the divisive berm and trestles, but once there was no longer fear of a collision at the grade crossing, cars could go racing at high speed along Route 20 through the little community.

In his Enterprise column, the Fullers’ correspondent bemoaned that the “changed appearance of the country with its trestle and huge banks of dirt is no improvement” and complained about “the rate of speed at which motorists tear through the new underground crossing at this place ….”

Digging an underpass without adequate drainage created an additional problem for Fullers. A February 1930 thaw accompanied by a rain storm flooded the underpass with more water and mud than the usual flooding.

Conditions became so bad the State Highway Department was called in with flagmen to warn approaching drivers, and trucks were sent in to pull out marooned cars and set up pumps that worked to lower water levels. Underpass flooding remained a periodic problem until the mid-1990s when an expensive reconstruction project there sought to end flooding on Route 20.

In 1941, the town of Guilderland purchased the land used to mine gravel to build the approaches to the Guilderland Center overpass and the huge berm to change the gradient of the tracks at Fullers. Today it is the location of the town highway department and town transfer station.

The original overpasses deteriorated due to age and use. In the 1980s, both the Frenchs Mills Road and West Old State Road overpasses were permanently closed to traffic while the heavily used Route 146 overpass at Guilderland Center was replaced in 1984 slightly to the south of the 1927 overpass with new entrances to the Northeastern Industrial Park.

Today, grade crossings such as those at Stone Road and County Line Road, the two West Shore crossings in Guilderland where the Public Service Commission did not insist that the New York Central construct a West Shore overpass or underpass, have modern-day electronic gates with sensors to automatically lower them when a train approaches, warning drivers.

The New York Central Railroad and its West Shore Division are long gone, but these tracks are currently used by numerous CSX freight trains daily. Drivers are grateful that with the Guilderland Center overpass and Route 20 underpass traffic moves quickly and safely instead of being stopped idling while a lengthy freight rolls through.

Editor’s note: Rail Safety Week runs from Sept. 20 to 26 in North America this year. About 2,000 serious deaths and injuries occur each year around railroad tracks and trains in the United States; last year, 19 New Yorkers lost their lives due to collisions with trains, according to New York State Operation Lifesaver.

This is the second and final part telling the saga of the Kushaqua. The first part, “The Kushaqua: Colonel Church’s ‘mammoth hostelry’ rises on the shoulder of the Helderbergs,” was published on July 26, 2021.

Following Dr. F.J.H. Merrill’s decision in 1902 to lease his summer home, the Kushaqua reverted to its original function as a country resort hotel. H.B. Smith took over, investing in extensive renovations to update the building, renaming it the Helderberg Inn. His venture proved a failure with the inn going into receivership.

A large ad appeared in The Enterprise, announcing “Receiver’s Sale March 24, 1904” to be held in front of Albany City Hall. Parcel No. 2 was “the beautiful hotel property known as the Helderberg Inn situated at Altamont.”

Also listed were parcels 3 to 7, land and farms associated with the hotel. The following day at the inn itself, “all personal property contained in and about the hotel” was to be included at auction.

F.H. Peterson next attempted to make the hotel profitable, but after two years it was again a financial failure.

The affluent summer colony members who owned “cottages” in the hotel’s vicinity had grown increasingly nervous about the fate of the inn. A brief article appeared in The Enterprise on Oct. 7, 1907, announcing the sale of the hotel and surrounding land to a syndicate composed of eight men owning property nearby, including J.B. Thacher.

The Enterprise noted that their purchase came after “learning that it was to be sold, determined to become owners that the conduct of the hotel should be to their liking.” Perhaps it was to the relief of Altamont villagers as well, seeing as the article concluded, “The transfer of this property to these people is an assurance that it will be conducted as a high class hostelry.”

Rapidly, the automobile had become the favored form for transportation among affluent Americans, making the steep original road from the village to the hotel a challenge for early cars. Within a year after the syndicate’s hotel purchase, a new road with a grade of less than 7 percent was opened, which “fills a long felt want,” built through the efforts of syndicate member and Albany businessman Gardner C. Leonard.

The Helderberg Inn syndicate footed the bill. A year later, the state highway commissioners were entertained at dinner at the inn by syndicate members during which they discussed a proposed route for a state road from the village. By October, a survey had been made for the proposed road with a good grade that avoided sharp turns, finally completed in 1911.

A 25-page booklet or prospectus, undated but probably from 1914, gave a detailed description of the facility. Available for guests were 55 guest rooms, featuring hot and cold running water with modern plumbing in private or semi-private bathrooms.

The inn was warmed by steam heat and, as soon as electric lines were strung out to Altamont, the hotel was completely wired. Ample telephone facilities were provided. Fresh flowers from the hotel greenhouse were always placed throughout the public rooms.

Hotel guests had access to dining rooms, lounging rooms, a ballroom, a sun parlor, and the piazza. Indoors, energetic vacationers could bowl in the inn’s alley; play billiards, ping pong, or a game called bolero; or climb to the observation tower.

Sedentary folks could enjoy reading a book or magazine from the hotel’s 2,000-volume library or relax in front of one of the inn’s many fireplaces. Additional outdoor activities such as horseback riding, tennis, and camping were added over the years.

Meals and service were described in the brochure as “perfect.” Food was “delicate and delicious,” carefully served. There was no bar, but vintages in the cellar were available by request, seeking to please both temperance folks and tipplers alike.

Service was available day and night from servants “selected with care.” Each day, afternoon tea was served, weather permitting on the piazza or in the walled garden. Guests were assured that there was “all white service throughout,” reflecting the intense prejudice of the day.

During the years that the syndicate owned the inn, it was renovated and updated as a series of managers attempted to develop a profitable resort. There were always a number of long-term vacationers, but hardly enough to fill 55 rooms.

It had become increasingly common for Albanians to drive out for only the day or weekend. Hops, dances held each Saturday evening, and tea “dansants,” dances held at Saturday tea time, were fads in that era.

Many who had driven out remained for dinner and then danced the evening away to an orchestra at the hop, often remaining overnight. It became a destination for auto or driving parties who appreciated the “bountiful supply of well cooked food for their Saturday and Sunday outings.”

Catered banquets or luncheons, sometimes mentioned in The Enterprise, provided an additional source of income. The Altamont High School Alumni Association June banquet was held there several years, while a luncheon for 70 ladies, members of the Eastern New York Branch of Collegiate Alumnae Association took place one summer. The University Club of Albany came out one Saturday, played a pick-up game of baseball, staying on for a banquet and dancing.

Briefly, a golf club

As years went by, the resort hotel business, proving to be a losing proposition, resulted in the formation in October 1914 of the Helderberg Golf Club Inc. Gardner C. Leonard, whose summer home “Hardscrabble Farm” adjoined the hotel property, had designed a prospectus, describing the advantages of the hotel, grounds and plans for a golf course and winter spots.

Obviously the syndicate members hoped this would be a financial way forward. Local Rotary Club members were being approached by Leonard, who urged them to buy $100 bonds in the operation, automatically giving the membership in what was characterized as a “model golf club” by its promoters

The Albany Evening Journal, when describing the proposed golf club, noted the owners had purchased it “some time ago to maintain the character of the neighborhood.”

The spring of 1915 brought word that the Helderberg Golf Club was being “thoroughly overhauled with extensive alterations and improvements to the club building as well as the grounds” where a nine-hole golf course was constructed. When the club shut down for the season that year, “a most satisfactory season” was reported.

The club reopened in 1916, but there were very few references to it in The Enterprise and it can’t be determined if it operated in the summer of 1917. In December 1917, the property was again on the auction block, this time selling at a huge loss considering all the money that the syndicate had invested in maintenance and upgrades in the years since they had acquired it.

The $100 bondholders would have lost as well. The purchaser was Frank A. Ramsey, representing Ramsey and Co., real estate brokers of Albany, who paid $9,100 for a property valued at $100,000.

Convent of Mercy

It soon became apparent the new owner was the Catholic Diocese of Albany, which planned to use the former hotel as a summer residence for the Sisters of Mercy, nuns who did a tremendous amount of work in the diocese. The old Kushaqua now became known as the Convent of Mercy.

By 1918, the United States was deeply involved in World War I. As casualties began to mount, places of respite were needed where wounded and gassed soldiers could heal and recuperate.

Albany Bishop Thomas Cusack wrote directly to President Woodrow Wilson, offering him the property for these men, giving Wilson a description of the building and grounds.

The government had requested use of hospitals and summer resorts for these men, but nothing came of Cusack’s offer due to its location being far removed from coastal ports, making it too difficult to transport these seriously affected men to the site. Perhaps after gaining possession of the property, Bishop Cusack had now begun to realize just what the diocese had taken on.

The bishop’s prayers were answered when, in 1921, Rev. Simon Forestier, acting for the Missionaries of Our Lady of LaSalette, purchased the property from the Diocese of Albany with the plan that the property be used to train seminarians studying for the priesthood.

Four years later, the structure had been renovated, looking nothing like the original hotel building. For over 20 years, the building acted as a seminary, junior college, and novitiate for this order.

Early on the morning of Oct. 25, 1946, as the seminarians, resident priests, and lay brothers were eating breakfast in the first-floor dining room, the smell of smoke became obvious. A fire, which seemed to have begun in the attic, began raging, spreading rapidly throughout the old wooden building

Fire apparatus quickly rolled in from Altamont, Guilderland Center, and the Army depot. Two trucks were sent out from the Albany City Fire Department.

Even with the arrival of the firemen, within an hour the seminary was consumed by a blaze driven by high winds. Flames were reported to have shot up several hundred feet in the air. Inadequate water supplies simply could not quell the out-of-control blaze in the huge wooden structure.

Fortunately, because all the residents had been downstairs at breakfast when the fire broke out, there were no injuries, but a valuable library was destroyed and all personal property was lost.

The LaSalette Fathers immediately began to rebuild on the site and, in 1953, opened the current building that stands there today. It was used as a seminary until 1979, when the lack of men wishing to enter the priesthood led to a change in the use of the building.

For a time, it was known as LaSalette Christian Life Center and Shrine. But, in 1984, the LaSalette order sold the building and land on the west side of Route 156. Father Peter G. Young began to use it as a treatment center for alcoholics who had been convicted of nonviolent offenses, which operated there for many years.

In 1886, one of Colonel Walter S. Church’s original ads for the Kushaqua emphasized his resort’s healthy location and its role as a recuperative resting place. Twenty-eight years later, Gardner C. Leonard continued to emphasize the proposed golf club’s invigorating, healthy location with dry bracing air.

Today the Peter G. Young Health and Wellness Center continues this long tradition of seeking health there, begun 135 years ago.

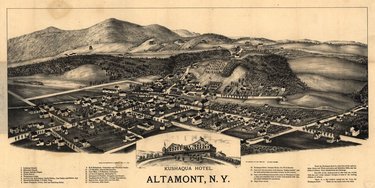

— From the Library of Congress

This early artist sketch of the Kushaqua paired with a panoramic view of Altamont illustrated the hotel when first opened. Helderberg Avenue is visible going up a steep incline, creating difficulties first in construction and after the hotel’s opening in shuttling guests and luggage from the D & H depot to the hotel.

Perhaps it was the influence of the comments of an 1881 Albany Evening Journal writer who claimed, “Tourists and summer boarders have flooded to the Helderbergs,” where local homes and hotels were “crowded to their utmost capacity.” It was a puzzle to him why no enterprising man had erected a summer hotel on such a “splendid site” in the hills, noting that wealthy Albanians had already begun building summer cottages in this beautiful, healthy location, easily reached by a short train ride from Albany.

Col. Walter S. Church, no stranger to the Helderbergs, seized the opportunity to be that man, taking on the project of erecting a fine resort hotel designed to appeal to an affluent crowd. In 1885, construction began on the crest of the escarpment overlooking the village of Knowersvillle, while below the hill curious locals followed periodic reports about what was initially referred to as “Colonel Church’s boarding house.”

His name had become linked to the area decades earlier when in 1853 he purchased leases to farms in the Hilltowns and surrounding area from the Van Rensselaer estate, planning to profit from dunning tenant farmers to pay both back and current rents. Over the next 32 years, through endless court cases and severe law enforcement by a succession of sheriffs and the New York State National Guard, he aroused the enmity of local farmers.

Anti-rent agitation ran high, but Church, a forerunner of the modern lobbyist, both forestalled any proposed anti-rent legislation at the Capitol and influenced the outcome of court cases by royally entertaining legislators and judges at his Albany home. Now he turned to creating a luxury resort to be called the Kushaqua, not only to be profitable, but probably to be his monument.

Building big

Construction of the hotel began in the autumn of 1885 when workmen began excavating the foundation on what had been farmland. Reports circulated that Church was building a three-story, 40-by-60-foot building. Excavation was complete by December and foundation work would begin, using the barrels of cement and carloads of sand that came through the D & H depot.

Hauling construction materials up steep Helderberg Avenue, the only road to the top at that time, was a major project in itself. By January 1886, the foundation was laid. Huge quantities of lumber had been shipped in and, as the structure neared rough completion, the windows arrived.

Spring brought Col. Church, accompanied by surveyors, to plot the location of a reservoir, using nearby streams and springs to supply hotel needs. Around this time, The Enterprise reported the colonel was expanding the size of the yet-unopened hotel an additional 84 feet because the original guest rooms were already booked. Within the walls of his new hotel, he had included parts of the original early 19th-Century farmhouse that had stood on the site.

Next Church secured an agreement with the Hudson River Telephone Company, paying the company to run a line out from Albany to his new hotel. At the time of the Enterprise report, the wire had already been strung out to Guilderland with the intention of running it out the turnpike to Dunnsville and then over to Knowersville.

Simultaneously, the two Knowersville hotels installed telephones as well. “Hello, hello!” was first heard in Knowersville when the Albany County Clerk called Church at his soon-to-be-opened hotel, according to a report in the Albany Argus.

Whatever amount Col. Church paid the phone company to run lines out to his hotel was repaid many times over three years later when fire was discovered in the hotel kitchen with smoke beginning to pour out the north wing windows. A hurried telephone message for help to Altamont (the village’s name changed in November 1887) brought a crowd of volunteers racing up Helderberg Avenue to man a bucket brigade from the hotel reservoir. Discovery that the fire’s location had started near a bakery oven and was beneath the floor brought it under control by ripping up the floorboards and saturating it.

Diverse attractions

Vacationers arriving on opening day in mid-June 1886 found reception and dining rooms on the first floor along with private parlors, card and supply rooms, and a barber shop. After registering, they would have been shown to one of the more than 50 guest bedrooms on the second and third floors, advertised to have “absolutely perfect sanitation conveniences.” The cuisine “would tempt the most exacting.”

In the basement level could be found a billiard room, children’s and servants’ dining rooms, kitchen, and storerooms. Available to guests were facilities for croquet, lawn tennis, and bowling. At the time of the Kushuqua’s opening, The Enterprise noted, “We have no doubt that Colonel Church is sparing no expense in the fitting up of this mammoth hostelry, and we have no doubt it will be well patronized the coming season.”

In addition to its newness, the main attraction of a stay at the hotel was its spectacular setting at almost 1,000 feet elevation. Bringing refreshing, cooling, healthy breezes, the site provided sweeping views over to the new capitol and church spires of Albany, east to Vermont’s Green Mountains and toward Schenectady where snatches of the Mohawk River could be seen.

Conveniently located only a half-hour train ride from Albany, The hotel welcomed arriving guests at the depot with conveyances to transfer them up to the hotel, their luggage hauled behind by wagon.

Rest and recreation were the key aspects of resort experience in the 1880s and ’90s. Strolling or lounging on the piazza to see and be seen took up time each day.

It was important to have reports seen in Albany newspapers that someone as important as Governor David Bennett Hill and his secretary, prominent Albanian Colonel Wiliam Gorham Rice, were walking on the piazza at the Kushaqua to attract future patrons. Landscaped grounds had paths for walking about, lawn tennis and croquet for the younger set, and “rambles” on local country roads.

Evenings at the hotel brought entertainment, often “hops,” the name given to informal dances in those days, when an orchestra was brought in. There were private parties such as the one given by the young woman who arranged to have a hop for 50 of her friends who then dined on an “elegant spread” afterward.

Guests seemed to greatly enjoy participating in entertaining themselves and were delighted to see their names reported in the Albany papers. One woman sang a selection of sacred music “most exquisitely rendered.”

Another evening, guests presented a series of “tableaux vivant” with people posing in costume to form a living picture such as the “bachelor’s reverie” displaying a “succession of really beautiful girls hovering in fascinating spirit form over a young man, presumably in a state of mental inertia;” while the “cabbage patch” proved to be a “galaxy of maidens peering through green paper tissue haloes,” etc. For this event, local people were invited up from the village.

An elocutionist gave readings and ladies performed charades, two more samples of the types of activities found at a resort hotel of the era. On occasion, an outside group such as the Knowersville Band was invited to perform. The Albany Evening Journal described life at the hotel one summer as “quite gay” with “entertainments of a high order.”

Newspaper reports told of nothing but success for the hotel. After the Kushaqua’s first season, The Enterprise claimed it was a “decided hit” certain to be one of the “most frequented resorts in the country in the future.”

The Albany Evening Journal reported in 1888 that the hotel had “unprecedented success the whole season.” A year later, a cool, wet summer didn’t seem to affect the visitors to the Kushaqua, which had its most successful season. Things always seemed to be going well at the Kushaqua.

Money pit

Yet in December 1890, after a short illness, Col. Church died, bankrupted by the overwhelming expenses of constructing and running the huge hotel. Resorts such as Saratoga, Lake George, and even Round Lake received much more coverage in the Albany newspapers and provided many more attractions than the Kushaqua.

Leased the next year by the Church estate to two New York City hotel keepers, additional money was invested in the building when steam heat was installed. In spite of the improvement, their venture failed and in 1892 the hotel was sold at a huge loss.

Unfortunately, Church underestimated the financial drain when, back in 1885, he was quoted as saying to a friend, “I don’t know I have gone in too strong, but I guess I can make a go of it.”

The hotel’s purchaser was Dr. F.J.H. Merrill of Albany who intended to use the building and surrounding grounds as his summer cottage. He paid $15,250 for the hotel, outbuildings, and property that had cost Col. Church between $60,000 and $75,000 (estimates ranged as high as $100,000). The hotel furniture was removed and shipped to Albany for auction.

Dr. Merrill, the director of the New York State Museum, was a geologist who shortly after was named State Geologist. Immediately, Merrill began making improvements to transform the hotel into a comfortable country home.

Employing almost 25 men at one point to make repairs, he added a new kitchen and laundry while the interior was rearranged for a reception room or hall through the center. Most of the old house that Church had kept within the hotel walls was removed.

At the same time, the large addition Church had added for the accommodation of hotel workers and a laundry was torn down. Merrill also ran the farm that was part of the property, even entering animals at the Altamont Fair.

Additional purchases of land were added to the property and cottages built with plans to rent them out to summer vacationers. The Merrills retained the former name Kushaqua for their summer “cottage.”

Similar to other residents of Altamont’s summer colony, the Merrills sometimes entertained on a scale unlike the locals. On one occasion, a trainload of Albanians arrived in Altamont, were transported up to Merrill’s cottage for a tea party. Most of the guests returned to the city after the refreshments, but a select group remained on for dancing to an orchestra. Governor Benjamin Barker and his wife were guests on another occasion.

Professor Merrill’s ownership of the Kushaqua suffered the same fate as Col. Church’s — their wonderful summer home and estate had become a money pit. The autumn of 1902 brought the announcement that it had been leased by H.J. Smith to be operated in the future as the Helderberg Inn.

Editor’s note: The saga of the Kushaqua will be continued in Mary Ellen Johnson’s next column.

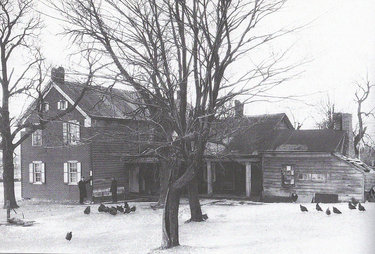

— From the Guilderland Historical Society

This photo of the rear of the Freeman House was taken as part of the 1930s Historic American Buildings Survey. The original Dutch door remains on the front and the house has been carefully preserved. Once a Dutch barn stood nearby, but it burned in the early 20th Century.

Contemporary Guilderland’s familiar landscape is for the most part suburban developments, strip malls, shopping centers, paved roads and parking lots, and apartment complexes. From our vantage point in time, it’s almost impossible to visualize our hometown 200 or 250 years ago, covered in virgin forest or pine bush, broken here and there by streams and swamps.

Once part of New Netherland, the colony established along the Hudson in the early 1600s by the Dutch West India Company, the area was taken over by the English in 1664 and renamed New York.

Evert Bancker of Albany, reputed to be the town’s earliest settler traveled up the Normanskill by canoe, establishing a farm in the area near today’s Tawasentha Park. Followed by other Dutch settlers and a few Germans, farms began to be scattered about in what is now Guilderland. All were tenants on the West Manor of Rensselaerwyck, expected to pay an annual rent in crops to the Van Rensselaer family.

While it is difficult to picture Guilderland’s physical surroundings in the 18th Century, the people themselves are so distant from us as to challenge our imagination. Looking back to this period, what can we reconstruct of the lives of these early settlers?

Worship

Dutch and German were their first languages and their early church records were in those languages. Dutch settlers, members of the Dutch Reformed religion, and German settlers, adherents of the Lutheran religion, were each visited sporadically by circuit-riding ministers. The Dutch Reformed Church had its formal beginnings in 1767 when the first church building was erected, but even earlier there had been a log meeting house used. Services were in Dutch until 1788 and their written records were kept in Dutch until 1796.

St. James Lutheran Church officially began as St. Jacobus in 1787 by the town’s German settlers with the erection of a small church building. Within a few years, the name was anglicized to St. James. Previously, when the minister came to our area, he held services in local homes. Pastor Sommer noted (the original in German) in August 1762, “I preached below the Helleberg in Michael Friederichs’s house and administered the Lord’s Supper.”

The earliest written records from St. James were in German as well. An indenture written for Patroon Stephen Van Rensselaer with the Minister and Deacons of the Reformed Protestant Dutch Church of the Helleberg mentions Low Dutch and German language services.

Houses

Although some of the early settlers here were German, they originated in that part of Germany that is adjacent to the Netherlands, and shared much material culture. Few of their early homes survive in Guilderland, unlike some other areas in the Hudson Valley, but fortunately a few photographs survive showing the Dutch influence on one early farmhouse.

Built of locally made brick and laid in the traditional Dutch style, a house photographed in the 1930s has been covered with stucco, but a later picture shows the stucco removed and the bricks clearly showing. Possibly built around 1700, it is the oldest house in Guilderland. But, since the 1930s photograph, owners did extensive remodeling, changing the character of the house.

Another early Dutch house was the Wemple house, taken down when Watervliet Reservoir flooded its location.

The oldest frame house in town is the Freeman House in Guilderland Center, reputed to have been built in 1734. In a 1966 interview, Mrs. Robert Davis, who with her husband were then owners of the house, mentioned the original Dutch door and that they had uncovered Delft tiles in the fireplace when they uncovered it. The Dutch typically had jambless fireplaces, having no mantel or sides, decorated with Dutch tiles.

A 1930s photo showed that the house still had its front stoop, another characteristic of Dutch houses.

The gambrel roofs on two of them reflect English influence, however. It’s possible there are other old houses in Guilderland that have some evidence of Dutch influence, but it has often been obliterated by later additions or remodeling.

Barns

Beginning with Evert Bancker, farmers needed barns to store crops and keep their animals. Early farmhouses were small, but nearby there would have been a large Dutch barn, the predominant barn style in our area as late as the 1820s.

These barns had a framework of beams that was a series of H’s supporting the roof. No nails were used, only wooden pegs. At the gable ends were wide doors to allow wagons to enter and exit. Small doors on each side of the front corners let animals in and out.

The side walls were low and the barn had a boxy shape. At the gable peak were holes called martin holes to allow swallows to fly in and out.

In the interior, a wide center aisle ran the length of the Dutch barn, a space where wagons could be unloaded and grain could be threshed using a flail or with horses dragging a length of wood over the wheat in a circular direction. On each side of the center aisle was a space for equipment storage or to house livestock. By laying saplings across the beams, farmers could lay sheaves of grain or hay for storage.

These barns were extremely well built using the virgin timber available at that time and, if maintained, have lasted until the present day, including several in the town of Guilderland.

Near the barn would have been a hay barrack, a structure with five upright poles and a roof that could be raised and lowered depending on the amount of hay to be stored and kept dry. This storage method was typical in the Netherlands and was copied over here, often being mentioned in descriptions by travelers.

Swedish naturalist Peter Kalm traveled through the Albany area in 1748, mentioning that everywhere he could see that type of “haystacks with moveable roofs.”

Farming

Mixed farming was the rule, with wheat the predominant crop needed to pay rent to Van Rensselaer for the farm. In addition to wheat, farmers raised garden produce, herbs, fruit, corn, oats, “pease,” and barley.

Kalm noted that around Albany local farmers could produce from 12 to 20 bushels of wheat from sowing one bushel. Every farm had livestock: horses, cows, sheep, chickens, geese, and pigs.

Dutch farms had definite differences from the English type of farm in New England. Grain and hay were cut by swinging a sith or scythe with a short handle in one hand and, holding a mathook in the other, supporting the crop upright to make it easy to cut. The farmer did not have to bend as low as he would have with an English-style sickle and, as a result, could harvest an acre in a day, two or three times as much as he could have with an English sickle.

Dutch wagons were also unique, having rear wheels larger than the front wheels. The front board was larger than the rear and spindles ran along the sides.

Dutch plows were also different from English plows, having a pyramidal plowshare, one handle and two wheels. Another observer visiting the Albany area in 1769 wrote that farmers “used wheeled plows mostly with 3 horses abreast & plow and harrow sometimes on a full trot, a boy sitting on one horse.”

Is there any evidence that this material culture was typical of Guilderland’s early farmers? In 1813, when George Severson, the proprietor of the Wayside Tavern on the “Schohary” Road (located where the Stewart’s Shop in Altamont’s is located today) and a farmer of the land surrounding his tavern died, an extensive inventory was taken of all his possessions and farm equipment.

A lumber wagon worth $40 and a pleasure wagon valued at $30 are listed, though there is no way of knowing whether either of them was a Dutch-style wagon. There is listed, however, one wheeled plow worth $10. Ten sythes are listed for $5 and three sythesnaths for $1.50, these being handles for the sythes, as well as two small hooks valued at 25 cents.

Also included was a skipple measure, this being a Dutch measure used instead of an English bushel. Since he also had half-bushel and peck measures, perhaps the skipple measure was no longer used by 1813.

Also listed were horses, sheep, cows, hogs, fowls, and geese along with two bee hives. Severson raised a variety of crops with amounts of wheat, oats, pease, flax, barley, hay on hand, and must have had an apple orchard since a “cyder” press was among his possessions.

Enslaved people

Dutch settlers had no qualms about owning enslaved people. Slaves had been brought into the Colony of New Netherland by the mid-1600s and the custom of slave ownership spread throughout the colony, continuing after the English takeover in 1664.

Sadly, in the midst of George Severson’s inventory of his possessions were two enslaved women who were sold at auction for $191. In 1810, the census showed that there were 66 slaves in Guilderland while in 1820 the number had dropped slightly to 47.

Certainly not every Guilderland family owned one or more slaves, but the 1810 and 1820 census records recorded which families did, how many and their ages. Finally, in 1827, New York State emancipated slaves within the state.

Fading Dutch culture

Gradually, by 1800, the Dutch culture had slowly faded, but it’s still possible to find bits of our Dutch heritage with place names such as Bozenkill, Normanskill, and Hungerkill, which still continue to be used. However, at some point, the Schwartzkill was anglicized to Black Creek.

When the town government was formed in 1803, it was given the name of Guilderland after Gelderland, the Dutch province that was the original home of the Van Rensselaer family. Old families anglicized their names: Oxburgers became Ogsburys, Friederichs became Fredericks, and Crans or Cranse or Crounce became Crounse.

The Helderberg Reformed and Altamont Reformed churches are direct heirs of the original Dutch Reformed Church while St. John’s Lutheran Church originated in St. James Lutheran Church.

A few of our town’s Dutch barns have survived to the present day, though sadly all too many have disappeared due to neglect or fire. When a 1947 wildfire that threatened the hamlet of Guilderland Center destroyed the orchards of Edward Griffith, wiping out his livelihood, he talked sadly about his great loss — his barn, which he said was historically valuable, dating from the 1700s, constructed of hand-hewn timbers with wooden pegs and its original doors.

Other Dutch barns have been removed to be re-erected elsewhere. The 200-year-old Ogsbury barn from just outside of Guilderland Center was taken apart in 1982 and moved to the Philipsburg Manor historic site in Westchester County to replace another Dutch barn that burned.

Fortunately, the Dutch Barn Society has been working since 1985 to record existing Dutch barns and to encourage their preservation in the areas of Dutch-German settlement.

While some residents in our town can claim to have had Dutch or German ancestors from among our town’s earliest settlers, sadly most modern-day residents are unaware of the town’s Dutch beginnings or even that the name Guilderland comes from a Dutch province.

— Photo from the Guilderland Historical Society

The only image of the Albany Glassworks known is this 1815 view of the glasshouse when it had been expanded from the time of the de Neufvilles’ operation. It is illustrated on script that would have been paid to a worker who could have used it to purchase goods in the community.

While this tale begins in 18th-Century Amsterdam, prosperous trading city of the Netherlands, it ends as a chapter of Guilderland’s history. Jean de Neufville and Leendert, his son and business partner, were among Amsterdam’s numerous wealthy merchants and bankers whose financial success was based on ownership of merchant ships, warehouses, and banks.

Descendants of Protestant Huguenots who fled French religious persecution in the previous century, the family prospered in the Netherlands. Jean de Neufville was an Amsterdam merchant who in the 1760s and 1770s traded in the Caribbean, and for several years was part owner of a coffee plantation on a Dutch island there.

As his wealth grew, he acquired a warehouse, a fine canal-side house at 224 Keizersgracht, and the estate Saxenburg at Wester-Amstel outside the city. Putting his profits to work, he established a banking partnership with his now-adult son.

The year 1776 brought the revolt of 13 of England’s North American colonies. Shortly after its outbreak, American representatives sailed to Europe, seeking financial aid and war materials to enable them to carry on their conflict against the British. While initially they turned to wealthy, powerful France, the prosperity of prominent Dutch bankers beckoned.

Loan not repaid

Jean de Neufville was sympathetic to the Patriot cause and in 1778 began shipping goods, including guns, to the United States. He had contact with the American representative William Lee and, acting on their own, the two signed a secret agreement. De Neufville had it approved by a Dutch magistrate and it was sent off to America on “The Mercury.”

Intercepted by the British, the attempt was made to throw the papers overboard, but they were retrieved. Sent back to England, the furious British precipitated the Fourth Anglo-Dutch War over the incident.

John Adams, then serving with Benjamin Franklin in France, was sent to the Netherlands in hopes of obtaining loans from Dutch bankers. One of the first bankers he met was deNeufville. The banker loaned Congress one million florins and also made a substantial loan to the state of South Carolina.

During this period, there was correspondence between de Neufville and both John Adams and Benjamin Franklin regarding the loan. At the war’s end unfortunately these loans and the lack of repayment led to the de Neufvilles’ bankruptcy in 1783.

Their homes and warehouse were sold. The de Neufvilles’ affluence, influence, and place in Dutch society were gone.

Jean de Neufville corresponded with George Washington in 1783, bemoaning “the ruin of credit of his house.” While some of the American loan had been repaid, South Carolina totally defaulted.

Washington responded in January 1784, “The disaster which happened to your house with which you were connected must be affecting to every true American, especially as your great zeal in the cause of liberty & your unwearied efforts to promote the interest of the United States are well known to the Citizens of the republic.”

Washington added, “I have the pleasure of being acquainted with your son.” If de Neufville had written to Washington, hoping to get some sort of favor, he received only pleasant words.

Opening a glassworks

Turning to the United States as the place to revive their fortunes, first Leendert and two years later, his father, Jean, and stepmother arrived in the United States. Here they became Leonard and John de Neufville.

In 1785, Leonard was in Albany County in a virtual wilderness on the bank of the Hungerkill on the edge of the pine bush west of Albany. On May 12, 1785, Leonard de Neufville signed an agreement with partners Jan Heefke and Ferdinand Walfahrt to open a glassworks in this location.

The site would provide sand for glass manufacture, pine to fuel the furnaces, and the Hungerkill’s steadily flowing water for use in the glass-making process or power equipment if needed. The potash needed in the manufacture of glass was readily available from local farmers who were beginning to clear trees from the surrounding countryside.

The probable motivation of the three partners was that, with the population growth and settlement of new areas in the new nation, there would be a demand for window glass.

De Neufville sadly underestimated the difficulties he would face in restoring his fortune by manufacturing glass in a wilderness spot two miles away from the King’s Highway, the main road into Albany. The connecting road was a narrow dirt track called the Schoharie Road. The Western Turnpike, which eventually provided a more direct connection, was years in the future.

It isn’t known where the three men got the capital — was it theirs or was it from silent American partners? — to build a glasshouse with furnaces and the necessary equipment. Money was given to Heefke to travel to German to recruit 24 or 25 glassblowers while in the meantime the glasshouse was being erected.

Their location was given the name of Dowesburgh or Dowesborough, the first of many names given to the hamlet of Guilderland.

By spring 1786, glassblowing could begin at the glasshouse with Heefke acting as the company agent and Walfahrt as the manager. Production consisted of small panes of window glass — measuring 6-by-8 inches and 7 by 9 inches — and of bottles ranging in size from small snuff bottles to large demijohns.

Native Americans living near the Wildehaus Kill at Dunnsville were paid to weave willow coverings for the demijohns — large glass bottles with small necks — to prevent breakage in shipment.

The glass was taken by ox cart over the Schoharie Road to the King’s Highway, then into Albany for sales there and for shipments to be sent downriver to New York City.

Their Albany agent was Wm. John Van Schaick who handled sales and shipping. Cash flow must have been limited as one of his letters related accepting two barrels of pork and 10 barrels of beef in return for a window-glass sale.

Jean, or John as he became known, followed his son to the United States, moving to Dowesborough in 1787. His optimistic letter to Colonel Clement Dibble of Philadelphia let him know that things were going well at the glasshouse, as they were able to match the prices and quality of imported British glass although he admitted the public considered the British glass to be superior.

He also noted that unfortunately the Hudson’s winter freezing delayed shipments to New York City, but in the meantime production was being stockpiled for spring shipping.

Bankruptcy

However, a year later a different picture emerged when John was visited where he was living in Dowesborough by Elkanah Watson. Watson was a prominent businessman, a founder of the State Bank of Albany and promoter of canals.

During the Revolution he had been in the Netherlands and France while in the employ of a Providence, Rhode Island merchant and was also involved in his own business there. While in Europe he apparently met the then-wealthy de Neufville and had kept in touch.

After his visit to de Neufville in 1788, Watson left a written commentary that he had “found him in solitary seclusion living in a miserable log cabin furnished with a single deal [pine] table and two common arm chairs, destitute of the ordinary comforts of life.”

Watson, who had grown progressively more affluent as he aged, must have been saddened seeing the reverses suffered by de Neufville.

Earlier in 1788, the three glasshouse partners — Leonard de Neufville, Jan Heefke, and Ferdinand Walfahrt — petitioned New York State Legislature for aid, justifying their request with the statistic that 30,000 pounds (dollars had not yet become part of our monetary system at this date) were being drained from the state by being paid to English glassmakers instead of being spent on state-made window glass.

Although their petition was ignored, the next year the partners repeated the petition. By the time the state finally came through with a loan, the glasshouse had become bankrupt under their ownership. Surviving letters tell of unfilled orders, lack of credit, and legal problems leading to the bankruptcy which seemed to have occurred by 1789.

Other investors took over the glassworks operation and achieved profitability until readily available fuel ran out in 1815 when the works were shut down permanently.

John de Neufville and his wife moved into Albany where he died in poverty in 1796. Leonard had a mental breakdown, supposedly one of several during his lifetime.

Likely the stress of trying to make a success of a glassworks in the wilderness was a factor in his final breakdown. He died in 1812 in a Pennsylvania institution.

After John’s death, the United States Congress agreed to award John’s impoverished widow a grant of $3,000 in recognition of her husband’s contribution to our victory in the Revolution.

Largely forgotten

Drivers on Foundry Road in Guilderland barely notice the historic marker, pointing out the approximate location of the glassworks that began there in the mid-1780s. The men who established it are obscure and their efforts met with failure. Leonard’s other two partners get no credit whatsoever.

Today, few know that the de Neufvilles played an important role in our victory over England in 1781 and seemed to be known to many of our founding fathers. Because of their support, the de Neufvilles lost their fortune, and in coming to America ended their lives in poverty.

Yet, they were among the first to settle in what is now the hamlet of Guilderland and, by establishing a glassworks and bringing in glassblowers, created a small community that has continued to grow.

While the de Neufvilles’ personal story was a tragic one, Guilderland residents can appreciate their contribution to the late 18th-Century history of our town.

The Enterprise — Melissa Hale-Spencer

Altamont’s Masonic Hall on Maple Avenue opened in 1913. Within a year, movies began to be shown on the second floor and, with some breaks, ran for four decades. The church next door, St. John’s, had been the site of Altamont’s first film entertainment, through a Bioscope in 1897.

Primitive systems of filming motion to be projected on a screen had been developed by the 1890s. Guilderland’s first opportunity to sample the new technology came in October 1897 when the St. John’s Ladies Aid Society sponsored a Bioscope entertainment two evenings in the Sunday School Room.

Advance publicity in The Altamont Enterprise claimed that the Bioscope, never before shown in the vicinity, was “the wonder of the age.” For an admission of 25 cents for adults and 10 cents for children, viewers could see the surging waters of Niagara Falls and President William McKinley on Inauguration Day.

But the main attraction was the New York Central’s Empire State Express filmed approaching at the rate of a mile a minute, making the onlooker “involuntarily scramble to get out of the way of the train. The wonderful realism of the picture makes the most unimaginative person shiver.” Front-row thrills were available for 35-cent reserved seats.

Noted in the next week’s Enterprise that the performances were “quite well attended and while the views were not brought out as clearly as wished for, owing to the operator being obliged to use gas instead of electric light, yet the wonder of the invention was fully demonstrated and the exhibition proved quite satisfactory.”

Their appetite for movies whetted, local filmgoers were able to see competing motion-picture technology when itinerant projectionists Hicks and Thomas Co. brought Edison’s Kinetoscope to the church a few months later. The audience must have been satisfied because the next week’s Enterprise judged that it was “the best in its line that ever visited our village.”

In 1903, at the Altamont Reformed Church, J.W. Achenbach was presenting a program billed as “The World’s Greatest Moving Picture Exhibition.” Viewers had the opportunity to see clips of Our Martyred President McKinley’s funeral, a Yale vs. Harvard football game, Little Red Riding Hood, a trip to the moon, and the Empire State Express at 80 miles per hour.

Attendees were guaranteed thrilling realism and no flicker or their money back. Admission was 25 cents for adults, and 15 cents for children.

Regular shows

The occasional motion picture was offered in Altamont and Guilderland Center over the next few years. With the opening of Altamont’s new Masonic Temple, regular, local moving-going became possible.

An April 1914 notice in The Enterprise announced to the public that Willard J. Ogsbury and Newton Stafford would offer an ambitious program of moving pictures, allowing viewers to see five reels for only 10 cents on Tuesday, Thursday, and Saturday evenings.

“First class,” and “giving general satisfaction” was the paper’s judgement the next week, noting the new venture had met “with good results as far as attendance is concerned.”

Quality improved quickly when within weeks a new lens was installed in their machine that projected a 9-by-12-foot picture on the screen, producing a larger and clearer image. In 1915, electrical lines were run into Altamont, allowing installation of a new electrical apparatus using an arc light that promised to show pictures “equal to any city theatre.”

Later that year, the eight-reel, big-budget spectacular “The Last Days of Pompeii” was shown by W.J. Ogsbury, now apparently the sole proprietor of the venture. Residents from Altamont and the surrounding area must have been entranced by scenes far from their everyday experience, watching fighting gladiators, chariot races, lions turned loose, and a vivid scene of the Mt. Vesuvius eruption engulfing Pompeii — all for 15 cents.

In 1915, a large notice appearing in The Enterprise advertised that the moving pictures were “Under the Management and for the Benefit of NOAH LODGE.” Five reels were to be shown regularly with an “expert operator in charge” on Saturday nights, for 10-cent admission.

By December 1915, shows were suspended due to lack of patronage, but must have been resumed at some point since, during the polio outbreak of 1916, a Board of Health order banning children under the age of 16 from attending public gatherings caused another suspension in moving picture shows at the Masonic Hall. “The management feels to continue the show under the present conditions would be unprofitable.”

The United States entrance into World War I was brought home to the local folks in 1918 when a movie benefitting the Red Cross was screened showing scenes of life in American training camps, activities of the army in France, and Red Cross personnel working behind the lines.

Charles H. VanValkenburgh, the theater manager, promised two reels of drama, two reels of comedy, and one reel of real life for 10 cents every Saturday night.

As the decade of the 1920s opened, movie-going had become established as popular entertainment for all ages. The Masonic Hall Theater, as it had become officially called, ran the longer features Hollywood had begun to produce.

Each week, the Village Notes column included the name of the next coming attraction, a synopsis of the plot, and listed those who were playing the leading roles.

Most of the films viewed no longer exist because, to the regret of film scholars, the material substance of early film has caused a huge number of them to deteriorate and crumble into dust in the cans where they were stored.

With Enterprise information, at least the names and plots survive of such long-forgotten movies as “The Night Horseman,” “Darling Mine,” “Whispering Wire,” “The Unknown,” or “A Stage Romance.” Occasionally, a film still considered a classic flickered across Altamont’s screen as when John Gilbert and Greta Garbo starred in the passionate romance “Flesh and the Devil.”

Talking pictures

“The Jazz Singer,” a 1927 movie that introduced the breakthrough of sound to audiences, changed movie history. Studios had been at first reluctant to adopt the new technology due to the high cost of new equipment to film the productions and then to theatres, which would have to refit with expensive new sound-projection machines.

But the audiences were clamoring for talking pictures, forcing the studios and theaters to move on. Most of “The Jazz Singer” was silent except for a few portions of sound recorded on discs that had to be played as the film ran, the operator carefully synchronizing the record to the film.

When “Saturday Night Kid” played in Altamont in December 1930, featuring Clara Bow’s “lovable, slangy, sloppy chatter,” Ray Rau handled the accompanying discs.

A brief announcement in June 1929 informed the public there would be no movies over the summer, though they were back in operation in September, managed by a party from Albany. In spite of the warning, “If Altamont people want their shows continued, they should support them by attendance.” By December, the unnamed Albany operator closed down the theater due to lack of patronage.

A week later, movies resumed under the management of Roy F. Peugh, who was joined by Ray Rau.

The issue of sound had reached a point where the decision had to be made: Close down or invest in new equipment to show sound-on-film productions.

In March 1930, a committee of Masons had been in Schenectady checking out a “sound outfit” there with the idea of running talking movies regularly. By December, it was announced that a talking-picture outfit was to be installed at once.

Finally, on Feb. 20, 1931, a front-page headline said “Altamont Sound Movies To Start With a Free Show.” Two Simplex projectors and a crystal-beaded sound screen were ordered by managers Peugh and Rau. The walls were padded with Celotex panels to provide the proper acoustics, all at a cost of $2,000.

Installed were seat cushions for everyone’s comfort with the seats tilted back one inch for better viewing. To operate all the new equipment, a second electrical power line had to be run into the building.

A public-inspection night was free, but the regular price of admission would now be 35 cents for adults and 25 cents for children. With the coming of warmer weather, patrons were assured not to worry about the heat since electric fans were now available.

Headlined “Talking Movies Big Success in Altamont,” The Enterprise reported the free demonstration night brought out 300 people who packed the hall, delighted at the perfect synchronization of voice and picture. Although at first only one projector was in operation that night, causing a delay between reels of “Cuckoos,” in time for the next Saturday’s showing the second projector would be in place for a non-stop performance.

Second life

Thus began the second life of Altamont’s little movie theatre.

The headline “Talking Movies Capture Altamont and Vicinity” reflected the enthusiasm the public from the village and the surrounding area felt about having talking pictures offered locally. Large audiences crowded the house.

During the Depression, the public turned to movies for escape and the modest admission cost at Altamont brought in a steady audience throughout the 1930s. Movies came to Altamont after their first-run showing in city theaters.

“Gone With The Wind,” one of the most successful and popular movies of all time, opened in 1939. Two years later, it finally arrived in Altamont for a two-day run. “Full Length Nothing Cut But The Price” read the half-page ad in The Enterprise.

During the war years, the theater provided much-needed escapist fare, but war-related films were often part of the schedule, some to boost morale as when the 1942 production “Our America At War” was added to the bill with the regular feature “Look Who’s Laughing.”

Others were far more serious; when and how to handle incendiary bombs was the topic of one shown to Civil Defense workers and volunteer firemen.

Movies continued through the 1940s and into the 1950s. Attendance had reached new lows by early 1957 and it seemed as if the show was over at the Masonic Temple.

In February 1957, an announcement appeared in The Enterprise that Jack Jalet, at the time a well-known Altamont resident, had the approval of the Altamont Business Association to manage the theater, being aware of “the need for entertainment in this village, especially for young people. Saturday matinees will be enjoyed by all.”

Jalet commented, “Hearing that plans were underway to remove the projectors from the Masonic Hall caused me to present a plan to bring back regular shows to Altamont.”

He proposed that each Saturday’s schedule was to include a two-and-a-half-hour matinée with the feature film and five to eight additional cartoons, then running an adult performance in the evening.

A week later, he wrote “An Open Letter to Teen Agers” in The Enterprise, requesting them to be quiet during the movies to allow the adults present to hear the dialogue. These customers would then return for future programs to help keep the theater open.

For a few weeks, longer movies were offered. However, in a blurb about the April 6 feature “A Yank in the RAF,” Mr. Jalet reported attendance was very disappointing and, unless more adults attended, movies would come to an end with the last show scheduled April1 13, a Dean Martin and Jerry Lewis comedy, “Pardners.”

Because The Enterprise ran no additional movie ads or mention of movies in the next few months, it seems the Masonic Hall Theater shows had come to an end.

Competition from TV, drive-ins, and more advanced film and sound systems in bigger city theaters put an end to our local show, just as happened to many small neighborhood movie theaters in towns and cities all over America at this time.

For over 40 years, the little theater had brought pleasure and entertainment to the people of Altamont and the surrounding area.

— Photo from the Guilderland Historical Society

The Case Tavern was one of the earliest of the Western Turnpike taverns and remained as a private home in the Case family until the 1940s. It burned in 1950. Its accompanying farm is now Western Turnpike Golf Course while the M and M Motel is located on the tavern site.

GUILDERLAND — The sight of a roadside tavern ahead meant an oasis where both weary travelers and their tired beasts could find respite and refreshment. In the 18th Century, very few taverns had been established in this sparsely populated area.

As years passed and traffic increased, it became obvious profits could be made from running a tavern, even if it were only a home’s front room or cellar where food and drink could be provided. Some were small establishments, while others were especially built as large taverns with ample room for overnight accommodations.

Palatines trekking to Schoharie created the Schoharie road, a dirt track road connecting the King’s Highway through what became Guilderland, Guilderland Center, and Altamont where the steep Helderberg escarpment had to be climbed to go on to Schoharie.

Guilderland’s first taverns appeared along this route, the earliest being Hendrick Apple’s tavern, which was noted on the 1767 Bleecker Map of the West Manor of Rensselaerwyck. In operation for decades, this tavern enjoyed local patronage as well as that of passing strangers and was the scene of Guilderland’s first town board meeting in 1803.

“Good moral character”

Apple’s tavern was one of many established along the Schoharie road. A list of tavern owners, having been judged “of good moral character,” who received licenses or permits in 1803 included Christopher Batterman in the hamlet of Guilderland where John Schoolcraft also ran a tavern although his name does not appear on this list. Nicholas V. Mynderse received a permit only, perhaps because his new building (now the Mynderse-Frederick House) was listed as a store, not a tavern.

It’s not known where the taverns that belonged to Nicholas Beyer, John Banker, Frederick Seger, Frederick Friedendall, and James LaGrange were located. George Severson’s Altamont tavern (now the site of Stewart’s) at the base of the escarpment had been in operation since the 1790s.

The licenses ranged in price from $5 to the $7.50 paid by George Severson. Henry Apple paid $9, which perhaps indicated fees depended on the quantity or perhaps varieties of liquor sold. Nicholas Mynderse’s permit carried no fee though a year later he paid $5.

A law had been passed by the Legislature of the State of New York on the first day of March 1788 entitled “An Act to lay a duty of excise on strong liquors and for the better regulating Inns and Taverns,” hence the “good moral character” qualification.

Another tavern owner, cited in J.H. French’s 1860 Gazetteer of New York, was Jacob Aker who ran an inn in Frenchs Hollow at the time of the Revolution. That seems to be the only reference to this tavern.

A second road running west from Albany through Guilderland out toward the Mohawk region was called the State road. The Guilderland section is today known as Old State Road.

Several men there received licenses at this time including Philip Schell, Peter Bowman, John F. Quackenbush, Jacob Totten, Abraham Truax, Wait Barrett, Benj. Howe, Frederick Ramsey, and John Wever.

The location of John Wever’s Tavern, in operation during the last quarter of the 18th Century, was known to be on the State road north of Fullers. In 1803, he met the qualification of “good moral character” and was permitted “to keep a public Inn or Tavern on the State road in the home where he now lives ….”

Pounds instead of dollars

Historian Arthur Gregg, having access to old documents relating to Wever, cited a 1792 receipt from liquor merchants Ten Eyck & Lansing of Albany for spirits purchased by Wever for his tavern: 6 shillings for 3 quarts of rum, 2 pounds for 5 gallons of wine, 1 pound for 3 gallons of Jamaica (rum?), 3 shillings for one bunch of segars and 1 shilling for1 pound of Bohea tea.

Old tavern account books recorded English denominations into the early years of the 19th Century. While the relatively new United States Congress had established the dollar as the unit of American currency and passed a coinage act in 1792, it took time before Americans in country places fully adopted the new federal money system.

Albany merchants must have had easy profits from supplying the multitude of country taverns in Guilderland and nearby towns, but with a shortage of specie they were willing to accept 21 sheppels of peas plus 3 pounds and 3 shillings cash from Wever in payment. (A sheppel was an old Dutch measurement.)

Great Western Turnpike

A few individuals received licenses for locations not clear to us today. Ezra Spaulding was on the Normanskill Road while Peter Taber was on the road to Schenectady. Gerritt G. Van Zandt was listed as being on the “new turnpike road,” the first of a large number of turnpike taverns along the route of the Great Western Turnpike.

During the later years of the 18th Century, William McKown, a tavern keeper on the King’s Highway between Albany and Schenectady, became acquainted with insider information that a group of investors planned to build a turnpike between Albany and Cherry Valley, an area attractive for new settlement.

He moved quickly to purchase a large tract of wilderness land on the proposed route of the new Great Western Turnpike. In 1793, when it was still wilderness, he built a large tavern there and shrewdly gave the investors financing the turnpike a right of way through his land, past the front door of his new tavern.

An adequate water supply was an absolute necessity for any tavern. Travelers may have been drinking liquor, but their animals needed water. McKown had a bountiful spring nearby and was also able to dam the Krum Kill in a few spots.

He cleverly used hollowed logs acting as pipes to bring a steady supply of water to his tavern and to the pens where animals were kept while their owners or keepers were at the tavern.

Entering a tavern, a man would find a variety of individuals in the room. Some were traveling for commercial reasons, others for personal reasons.

Certain large taverns would have had the regularly scheduled stagecoaches between Albany and Cherry Valley stop to change horses or spend the night. Other men were drovers who accompanied herds of sheep, cows, pigs or flocks of turkeys on foot to the markets in Albany.

Pulled by oxen and guided by teamsters, freight wagons came through, hauling loads of farm produce to market and hauling back commodities unavailable on the frontier. Local men also came in at times, and the air would be heavy with the smell of people and tobacco smoke.

Politics were great topics of discussion, debate, or argument. The Federalists and Democratic Republicans of that day definitely did not see eye to eye about policy or elected officials.

Local government meetings, political rallies, and voting all took place in various taverns. The few women who traveled for any reason would not have been in this mix of men, but in their own “ladies’ parlor,” away from the sounds, smells, and alcohol of the tap room.

When the Great Western Turnpike’s first section opened, it was the main road into southwestern New York and soon extended beyond Cherry Valley, carrying what for that day was heavy traffic of men, horse- or oxen-drawn vehicles, and a variety of beasts.

One author stated there were 62 turnpike taverns along the original 51 miles between Albany and Cherry Valley to serve the traveling public.

Going west in Guilderland, starting with McKown’s tavern in McKownville, a half-mile beyond was a tavern that would have been located just to the west of today’s McKownville Methodist Church. Known as Gibb’s Tavern, that may not have been its original name.

Possibly it was the one noted as being run by George Brown and/or Frederick Fallock. Or one of these men may have been the original owner of the structure later known as the Jackson tavern.

Moving on into the hamlet of Guilderland were Batterman’s and Schoolcraft’s taverns, which were also considered Schoharie road taverns. A mile beyond was Russell Case’s tavern, the next two places were run by men now forgotten, and another was at the house that until recent years stood opposite the Guilderland Town Hall.

Nicholas Beyer’s was next. Then came Traber’s, later called Fuller’s tavern. There was Gilbert Sharp’s and Jewell’s in the vicinity of Sharps Corners. Next came John Meyers, and then Simon Relyea.

At Dunnsville, there was John Winne’s tavern and store, Peter Gorman’s, Christopher Dunn’s and farther west a man named Slingerland ran a tavern. There may well have been additional taverns that have slipped through the historic cracks.

Costs

Assuming a traveler stopped for refreshment or for overnight lodging, what were the costs? Historian Arthur Gregg had access to an account book kept in the Severson tavern on the Schoharie road, the last stop before the arduous climb to the top of the escarpment

While travelers were the mainstay of big taverns such as McKown’s, locals also frequented taverns for news; to debate politics; in the case of Severson’s, to pick up mail; and, of course, quench their thirst.

An unnamed traveler stopping at Severson’s spent l shilling for a gill of whiskey (a gill is a quarter of a pint), 4 shillings for supper, 2 shillings to keep his horse, 1 shilling for his lodging for the night, 1 shilling for oats, and 6 pence for a gill of whiskey.

Mr. Lot Hurst came across with 16½ cents total for 1½ mugs of cider, 1 gill of whiskey, and 1 segar. The 1792 Coinage Act permitted half cents and many of the amounts charged included a half cent. John Wemple ordered a brandy grog for 12½ cents. There seemed to be no consistency in the prices charged.

Some of these taverns were also stores selling much needed goods that could not be produced on the farm. John Winne’s Dunnsville tavern/store sold items such as 1 pound of sugar for 12½ cents, a black tea pot for 35 cents, 5 yards of calico for $3.03, and 1 pound of candles for 25 cents.

Since a shortage of specie was common during this time, bartering was acceptable and Winne was willing to accept a cord of wood to equal $1, or 8 pounds of butterfor $1, or two dozen eggs for 18 cents, a day’s labor for 50 cents, 3 turkeys for 75 cents — all to be put toward merchandise available in his store.

End of an era

Taverns were reputed in their day to be good moneymakers, supposedly equal to two farms. With the opening of the Erie Canal in 1825 and the development of rail travel after 1832, the heyday of turnpikes and their taverns came to an end.

A few survived to become hotels such as the Dunnsville Hotel and the McKown Tavern, but for most an era had come to a close. With the passage of time, we no longer know where many of these taverns were even located and, one by one, Guilderland’s few old buildings known to have been taverns have disappeared.

— Photo from the Guilderland Historical Society

Meadowdale Station, once located next to the tracks on Meadowdale Road, was one of the Delaware & Hudson’s smaller depots. Notice the telegraph poles in the background. The National Telegraph Company had run lines between Albany and Binghamton along the railroad route.

Victory at Yorktown; ratification of the Constitution; George Washington’s death; the British invasion of Washington, D.C.; election of Andrew Jackson; outbreak of the Civil War; assassination of Lincoln — when and how did 18th- and 19th-century Guilderland residents learn of these events?