Glassworks along the Hunger Kill led to the birth of Hamilton, which the postal service later named Guilderland

— Photo from the Guilderland Historical Society

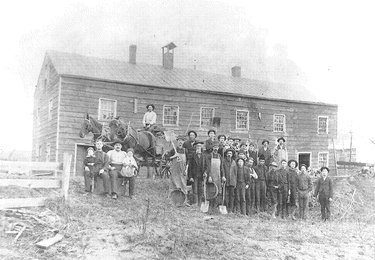

Workers at the foundry posed for a photo along with the draft horses that hauled finished iron products to the Fullers West Shore Railroad Station, returning with iron ingots to begin the manufacturing process. Sitting in front of the horses were owners Jay Newberry and George Chapman.

While thousands of drivers now pass through the hamlet of Guilderland daily, four centuries ago wilderness covered the area. Native Americans had worn a trail there leading south from the Pine Bush later followed by German Palatines in 1712 trekking to their new home in Schoharie.

As the 18th Century went on, other settlers followed the same route, settling in areas below the Helderberg escarpment in what is now the town of Guilderland. Within a few years, the trail developed into a dirt road known as the Schoharie Road.

This was the beginning of the hamlet of Guilderland’s history.

In the years prior to the Revolution, almost all of the town’s settlement was in the higher areas to the west, although a few Europeans did establish homes and a mill along the Hunger Kill close to its mouth with the Normans Kill.

Settlement really began in what is now the hamlet of Guilderland when, in 1785, Leonard de Neufville, a Dutch citizen, established a glassworks in the Hunger Kill ravine. Raw materials for glassmaking were readily available at this spot: a plentiful supply of water, sand, and wood for fuel. Window glass and bottles would be produced here with de Neufville hoping the new nation with its growing population building homes and other buildings would provide a growing market.

His father, Jean, and a number of German glassblowers joined him by 1787 in the tiny community they had named Dowesburgh. Conditions were difficult at first. A visitor to the de Neufvilles was appalled to find them living in “a miserable log cabin.” Conditions for the workers couldn’t have been any better.

And, to complicate matters, glass products had to be hauled into Albany via Schoharie Road and King’s Highway until 1800 when the Western Turnpike opened, providing a more direct route.

Improvement in living conditions came in 1796 when planning laid out what is now Hamilton Street and the route of the Schoharie Road shifted a bit to the west to run down Willow Street.

The little community now had the new name of Hamilton chosen to honor President George Washington’s Secretary of the Treasury Alexander Hamilton, a promoter of manufacturing in the new nation. Around this time, there were two taverns established adjacent to the Schoharie Turnpike, one operated by Christopher Batterman, the other by John Schoolcraft.

“Jedediah Morse’s Gazetteer,” published in 1798, remarked that in Hamilton were “two glasshouses and various other buildings with curious hydraulic works to save manual labor by the help of machinery,” calling it, “one of the more decisive efforts of private enterprise in the manufacturing line as yet exhibited in the United States.”

In spite of this favorable review, the glassworks had had financial ups and downs and changed ownership several times.

The Great Western Turnpike was being cut through in 1800 and, although charging tolls, would be an improved and direct connection between Albany and Cherry Valley, an area just being settled.

Once the Turnpike was completed by 1804, heavy traffic was rolling through the tiny community of Hamilton: regularly scheduled stage coaches; carriages; wagons pulled by ox teams; settlers moving west; and drovers bringing cattle, sheep, pigs and turkeys to market in Albany.

Blacksmiths and wheelwrights were needed with one or more established in Hamilton at an early time.

A few years later, the 1813 “Spafford’s Gazetteer” claimed the glassworks had an output of 500,000 feet of window glass annually. There were now 56 mostly small houses in the community.

Within two years however, the glassworks closed down because the plentiful fuel supply had run out in the nearby area and glassblowers and others involved with the glassworks such as Col. Lawrence Schoolcraft and his son, Henry Rowe Schoolcraft, moved on.

Other small-scale manufacturers moved into the ravine at various times during the 19th Century, including factories manufacturing woolen cloth, cotton batting, hats, and eventually an iron foundry.

By 1815, the Batterman and Schoolcraft taverns had operated for many years although it is not known when they closed. George Batterman, another member of the Batterman family, opened up a tavern on the south side of the new turnpike. His tavern was on a sizable piece of land and, to accommodate the animals that were brought along the turnpike, the property included barns, pens, and sheds.

A short distance to the west, Russell Case also opened a tavern although, when traffic was no longer heavy, it reverted to a family farm. Around the outskirts of the community, farms had been established and a member of the Batterman family had dammed the Hunger Kill to establish a grist mill just to the west of the village.

By now, the population had grown to the extent that the United States Postal Service opened a post office in what was then the most populous community in the town of Guilderland, assigning it the name Guilderland. If you’ve ever wondered why the hamlet came to be called Guilderland instead of Hamilton, that’s your answer.

Churches in Hamilton

Back in 1796, when Hamilton and Willow streets were laid out, an octagonal combination church and school building was also constructed. At first, various visiting ministers preached there, although usually it was a Presbyterian minister.

Finally, in 1824, the church formally became part of the Albany Presbytery, calling itself Hamilton Union Presbyterian Church. A Sabbath School was established and weekly prayer services were held.

Originally, the school which shared the building prepared boys for college, but after the 1812 state law setting up common schools, it educated boys and girls through the eighth grade. In 1834, the original octagonal building was removed and in its place a new larger church was erected.

The middle years of the 19th Century brought two other new churches to the community. A small Baptist church was erected in about 1840 on the south side of the turnpike. Within a few years, the Baptists left and a Catholic church took over the building for a short time.

After the Catholics left, the building remained empty until a temperance group called the Good Templars moved in and were active in the community during the later years of the 19th Century. Finally, the Order of Red Men also began to use the building. In later years in the 19th Century, it was usually referred to as Temperance Hall.

Guilderland’s Methodist-Episcopal Church, built on Willow Street in 1852, was the result of the growth of Methodism in Guilderland. A few years later, the church was jacked up and a cellar dug underneath with a parsonage purchased across the street.

It was also in these years that the Hamilton Union Church purchased its first parsonage to the east of the church, then, after a few years, sold it, replacing it by purchasing a home directly in front of the church.

Two grand homes and a grand hotel

The 1840s brought the community the construction of two beautiful homes. One was John Schoolcraft’s Gothic Revival summer home.

Schoolcraft, a local boy who had grown up in the hamlet, moved into Albany where he achieved great success in the business world and became friends with politically influential people. Located on the turnpike opposite Sloan’s Hotel, his new home sat on 10 acres stretching back from the road.

Farther to the east on the turnpike was Rose Hill, built in 1842 by John P. Veeder, which remained in family hands during the remainder of the 19th Century.

When George Batterman died, his tavern was left to his daughter and son-in-law, Henry Sloan, who then ran it until at some point in the 1840s it burned. When Sloan rebuilt, it had become a larger hotel, which became well known for its hospitality, attracting everyone from the governor and wealthy Albanians to ordinary travelers.

The hotel was often the scene of political rallies, both Republican and Democratic, and for donation parties for the Presbyterian minister.

For a time, the area was even called Sloan’s.

Prospect Hill Cemetery opened in 1854, having obtained 50 acres from John P. Veeder. It was one of the then stylish rural cemeteries in fashion at that time.

A decade later, its officials set aside an area of land where Civil War soldiers could be buried in a free plot. As the observance of Memorial Day became an important feature of 19th-Century life, the cemetery became the focal point of local Memorial Day ceremonies and had as many as 5,000 people there for the occasion later in the century.

Willow Street in the hamlet itself was the starting point for the parade to the cemetery.

A look at the small hamlet is provided by the 1866 Beers Map, which shows the Presbyterian, Methodist, and Baptist churches; Swann’s marble yard where gravestones were fashioned; a doctor, Sloan’s Hotel; a mill; a carriage shop; two parsonages; Weavers store; a hat factory; several houses; and a school.

The school had moved to a building on Willow Street separate from the Presbyterian Church in 1843.

As the years passed, the small 1834 Hamilton Union Presbyterian Church needed replacement. Taken down to make room for a new larger church, the new building opened in January 1887. The Meneely bell, which had been purchased in 1865, was rehung in the new steeple.

Foundry booms, then leaves

At some point after the publication of the 1866 map, the hat factory was gone, replaced by an iron foundry run by Wm. Fonda. Ownership then passed to two brothers-in-law, Jay Newberry and George Chapman, who quickly began to expand its capacity with replacement of the original building and the purchase of additional acreage of land.

Immediately successful, the foundry’s draft horses hauled finished iron products out the turnpike to the West Shore Railroad station at Fullers, returning to the foundry with iron ingots for production.

Employment increased steadily with 25 workers in 1886 and twice as many in the 1890s. The population of the hamlet certainly grew and the foundry workers’ wages brought prosperity for the businesses.

Newberry and Chapman seemed to have treated their workers fairly and paid wages on time. Sometimes they provided recreational activities for the men as well. Neither labor unrest nor strikes ever were a problem here.

One night in January 1890, flames erupted at the foundry causing the loss of important buildings, but these were quickly rebuilt. Although a year later George Chapman died at age 31, Jay Newberry continued the business.

However, being so far from a rail line was a definite handicap and Newberry began to look to relocate the foundry. His announcement in 1896 that he was moving the foundry to Goshen, New York to be on a rail line was a shock to the community. The foundry was put up for sale, but it took until 1900 to find a new owner.

By 1890, the school age population had grown to such numbers that a new enlarged schoolhouse was necessary. That September, the teacher and the children used the Red Men’s Hall as a temporary schoolhouse while the old Willow Street schoolhouse was taken down, a new foundation dug, and a new two-room school was erected on the same site.

Later that fall, a second teacher was hired. The new school was opened for students and their two teachers in January 1891 when they returned from Christmas vacation. Opinion in the little community was that their new school “is the best in the county outside the cities.”

As the years of the 19th-Century came to a close what had been a prosperous rural community was faced with uncertainty. Many residents had to choose whether to leave in search of other employment, or stay in their familiar surroundings while, in many cases, extended family members relocated to Goshen.

The question of what would become of the site of the foundry must be determined.

Next month, we will follow the second part of the story of the hamlet of Guilderland with its transition into the automobile age and suburbia.