— Painting by John R. Williams

Jacob Van Aernam, Revolutionary war hero, and his barn, still standing on Brandle Road, just outside of Altamont, was painted by John R. Williams of Knox for a Van Aernam descendant. The Van Aernam cemetery is still there, too. Jacob Van Aernam is waving to Sam, an enslaved person whom, family lore has it, saved Van Aernam’s life.

Most New Yorkers know that slavery once existed here, but few are aware that not only the wealthy, but a large number of ordinary New Yorkers benefited from the labor of enslaved men and women. For two centuries or longer, slaves were toiling on many of Guilderland’s farms or in local taverns, their names and labors long forgotten.

Within a short time after the Dutch established the Colony of New Netherland in the 1600s, Africans were imported, beginning a history of slavery in New York that lasted until 1827. In the colony, and after 1776 the State of New York, slaves were more numerous than in any of the other northern states in the new republic.

In 1771, shortly before the American Revolution, Albany County counted 3,877 Blacks, almost all of whom would have been slaves.

A glimpse of slavery and the contemporary attitudes of Albany’s white citizens were provided by Mrs. Anne Grant in her 1808 “Memoirs of An American Lady.” Having resided in Albany for many years in the last decades of the 18th Century, she had ample opportunity to observe life there, concluding that local slaves were “happy in servitude, being generally hardworking and loyal to their masters.”

According to her portrayal, physical punishments were rare, but for the few who were really wayward slaves, neglecting their duties, stealing, being disloyal or partial to alcohol, the threat of being shipped to Jamaica to work on the sugar plantations kept most of them in line, she wrote.

Slave ownership did not seem immoral or to have bothered the consciences of Albany County slave owners. In their view, religious beliefs did not preclude people from slave ownership and, since mention of slavery had appeared in the Bible, slave owners “had not the smallest scruple of conscience with regard to the right by which they held them in subjection,” Mrs. Grant wrote.

Her conclusion that “the slaves were usually faithful and true to their masters and mistresses, as aside from their being bond slaves and chattels, their lot was comparatively happy” was an opinion that would have been typical of most New York slave owners of the time.

By the mid-1700s, early settlers had begun to establish homes in the area of Albany County that eventually became the town of Guilderland. Arthur Gregg, our late town historian wrote, “The old settlers seemed to have easily absorbed the idea of slavery and took pride in the rapidity with which they could afford them.”

Jacob Van Aernam was a colonial settler known to have owned at least one slave at the time of the Revolutionary War. Van Aernam family tradition claimed that, while an enslaved person named Sam — only his first name is given — was working with Jacob Van Aernam in one of his fields, Sam became aware of a rustling sound in the brush and immediately alerted his master. Van Aernam quickly seized the gun he always carried with him in those troubled times and, thanks to Sam’s warning, managed to rout a stealthily approaching band of Tories.

With the ratification of the Constitution, the extent of slavery in Guilderland becomes more carefully documented by the decennial censuses beginning in 1790. With 3,929 enslaved persons and 170 free Blacks, Albany County had more slaves than any other county in the state except New York City.

While at that time Gulderland was still part of the town of Watervliet, familiar Guilderland names stand out among a much longer list of Watervliet’s population. Henry Appel, owner of the Appel Inn, owned one slave; Jacob Van Aernam owned three, and Barent Mynderse owned four.

The 1800 census enumerated 412 enslaved persons living in the town of Watervliet. At this time, Henry Appel, Frederick Crounse, and Jacob Van Aernam each possessed five slaves, while Lucas Veeder and Barent Mynderse each owned four. Many others owned one or two.

Barent Mynderse, like Jacob Van Aernam, had been a local patriot who played an important part in the Revolutionary War. He was born and lived as an adult in the Freeman House, owning a sizable piece of land there.

His son was Nicholas V. Mynderse, who built the tavern that is now called the Mynderse-Frederick House in 1802 and a year later was elected first town supervisor when Guilderland officially became a separate town.

In the 1790 and 1800 censuses, Nicholas Mynderse does not show up in the records, probably because he was still part of his father’s household. Only the names of heads of households were listed in early United States census records; other family members were listed by sex, age, and race. By the time of the 1810 census, he had died. The question of whether his father’s slaves helped to construct or serve in his tavern cannot be answered without further documentation.

The northern antislavery movement became stronger in the years after the Revolutionary War, leading to the other northern states abolishing slavery one by one. In New York after the Revolutionary War, the number of enslaved persons actually increased with 21,000 slaves in servitude in the late 18th Century.

Although some New York citizens were in favor of emancipation, freedom for the slaves came slowly with much opposition especially from rural areas. Manumission — an owner freeing his slaves — became a major divisive political issue of the day.

Gradual emancipation

Finally, in 1799, the New York State Legislature passed an act gradually freeing slaves. The complicated law stated slaves born before July 4, 1799 would remain as lifelong slaves unless freed by their owner. However, a male born after that date remained a slave until his 28th birthday while a female remained a slave until her 25th birthday, both serving their mother’s master.

Included in the 1799 slave legislation was the provision that babies born of slaves after this time must be registered with the state. Also included was a clause allowing masters to collect a stipend if slave babies were freed within a year of their birth.

As a result, these children were paupers, allowing the overseer of the poor to make them bond servants of the masters who were then paid a monthly fee of $3.50 for each. This explains why in our early town records the following notices are quoted in the Howell and Tenney 1886 “History of Albany County, NY”:

“I do hereby give notice that my Negro wench Dianna was, on the 20th day of May, in the year of our Lord 1802, delivered of a male child named Simon, and that I shall abandon the said child agreeable to the act in that case made and provided. Dated this 28th day of April 1803. Frederick Crounse”

Similar notices were given by Peter Veeder, abandoning his slave Susan’s female child named Gin, and John Howard, abandoning his slave Gin’s male child named Yeat. Henry Appel abandoned three babies, all children of his slave Maria, born between 1801 and 1803, two boys named Jan and Joe and a girl named Gin. And James LaGrange abandoned a male child named Jock, son of Phoebe.

This law was so popular with slave owners that by 1804 the state had paid out over $20,000, a huge sum at that time. The legislature quickly revoked that clause of the law.

Slaves continued to be legally bought and sold in the state until the final emancipation law of 1827. In the Guilderland Historical Society Archives may be seen a 1793 sales contract between Casper M. Halenbeek of Coxsackie who was selling a “certain Negro wench named Zann (Fann?) aged twenty two years together with her child named Maria nearly two years old soundly without any ailments or old disorder” to Hendrick Shavier (Henry Shave?) of the Town of Watervliet for 65 pounds (Americans frequently continued to use English denominations in the years shortly after the Revolution).

George Severson operated a tavern at the base of the escarpment on the Old Schoharie Road (now the site of Altamont’s Stewart’s Shop) with the help of slaves. A Severson family member remembered a story told of an enslaved woman named “old Gin,” spinning before the fire in the late 1700s in the basement of the tavern.

When George Severson died in 1814, all of his worldly goods were inventoried in preparation for a public auction. Listed between 6 brooms with an estimated worth of $.75 and 7 feather beds estimated to be worth $70 was “1 Negro wench estimated to be worth $70 and l Negro girl $40.”

A year earlier, Severson had purchased the approximately 37-year-old Nan for $100 from a Schoharie man; the bill of sale and complete inventory are found in Chapter XXVII of Arthur Gregg’s “Old Hellebergh.” At the auction, both Nan and the nameless girl were purchased by one-time town Supervisor Peter Van Patten for $191, higher than the inventory estimate. Being that he paid a higher price than the estimate, it is likely one or more persons also bid against him to own these two women.

Although it was illegal to do so, in the years just before the end of slavery in New York, slaves were often sold South where they were in great demand. It is not known if any slaves in Guilderland suffered this fate.

Death

As chattel or personal property, enslaved people were part of a deceased person’s estate and were very often passed down to heirs. Jacob Van Aernam’s 1812 will left his slave Sam, his protector during the Revolution, to his sons, John and Thomas, and to his single daughter, Nancy, while to his daughter, Lany, “my young female slave named Chris” and to his daughter Nancy “my youngest Negro slave named Gannet.”

When enslaved African Americans died, finally finding rest and peace, their bodies were interred in the individual family burial grounds on their owners’ farms that existed before large cemeteries were established.

Arthur Gregg mentions the Severson family cemetery where “the graves of slaves are marked with simple fieldstones.” As for the Crounses, “south of their own graveyard may be seen that reserved for the Crounse slaves after their toil was over.”

William Brinkman, an earlier Guilderland town historian, wrote that on the Lainhart farm “colored people are buried in the southeast corner of the plot.” Since the 1810 census lists 37 Guilderland residents owning 66 slaves, there were certainly many other family plots where slaves had been laid to rest over the decades that slavery existed in Guilderland.

Finally, freedom

The 1810 census shows that, in addition to the 66 slaves in Guilderland, there were 54 “free Negroes,” the term used to describe Blacks at that time. Many households had a combination of slave and free Blacks.

Matthew Frederick’s household had one slave and two free Negroes while Barent Mynderse had three slaves and one free Negro. A few residents, such as innkeeper William McKown and John Fryer, each had one free Black person in their households.

Slowly, slavery was dying out. In 1820, the number of slaves had dropped to 47 with 25 free Negroes in town.

Political agitation to totally end slavery continued with strong dissention between the Federalist and Republican parties until finally, under pressure from Governor Daniel D. Tompkins, in 1817, the New York State Legislature passed a law freeing all slaves including those born before 1799 on July 4, 1827.

As sort of a postscript to slavery in Guilderland, in May 1894, an announcement of the death of “old aunt Dinah Wilda, colored,” appeared in the Guilderland column of The Altamont Enterprise. It explained she had been born in 1800 and purchased as a 6-year-old by a grandfather of Dr. Abram DeGraff, Guilderland’s well known doctor.

She remained with the family after the abolition of slavery for three generations and, according to the writer, “was much respected by all who knew her and was always treated as one of the family.” She wasn’t living in Guilderland at the time of her death, but her body was returned to her original home, where her funeral took place at Hamilton Presbyterian Church and burial followed in the DeGraff family plot in Prospect Cemetery.

Later in the 19th Century, as descendants of the original slave owners looked back, their attitude would have been much the same as Mrs. Grant’s. Their ancestors’ slaves were treated kindly and were happy with their lot in life, they maintained.

Howell and Tenney described the institution as “mild” in Guilderland. We know better.

Just imagine yourself being in the situation of the enslaved, overworked Sam or Maria or Nan. Imagine the fear for her future of the unnamed young girl who was auctioned off or of that terrified little 6-year-old Dinah purchased by Dr. DeGraff’s grandfather — and judge for yourself.

— Photo from the Guilderland Historical Society

Ward’s Store on Route 20 in Guilderland was one of many stores in operation during the Great Depression. Not only did it offer food, but served as the post office and had gas pumps as well. Note the WGY sign about the entry. In recent years, the building was taken down for Guilderland Fire Department expansion.

Imagine a family of four seated at their dinner table, sharing one or two frankfurters sliced into a bowl of macaroni covered with a tomato soup sauce accompanied by a side dish of a can of green beans or corn. Sound far-fetched?

During the 1930s, such a meal would not have been unusual for a family headed by an unemployed breadwinner or one whose wages and hours had been cut. While not every family in Guilderland was so impoverished, there were others who were suffering.

The following notice appeared in the Village Notes column in the Nov. 4, 1932 Enterprise: “While the thoughts of many of our residents are on unemployment relief, it might be well to remind ourselves that there are many others in need of help at this time of the year. The Enterprise knows of one case, not far from Altamont, where a middle-aged woman, who is caring for her little nephew, is almost destitute.

“She has been unable to obtain work of any kind. If this notice strikes a responsive chord in the hearts of those who read it, the Enterprise will be glad to furnish the name of the person needing help — or the Enterprise will receive and dispense gifts received from our readers. The need for help is urgent.”

By 1932, the unemployment rate in the United States had risen to 23.6 percent and a year later hit an all-time high of 24.9 percent.

Examples of local charity for the truly destitute made its way into the pages of The Enterprise at times, often involving young people. A Dec. 1, 1933 headline read, “Local High School Pupils Bring Thanksgiving Cheer.” The story described the efforts of Altamont High School students who raised $30, allowing them to fill 11 baskets with chickens, vegetables, and fruit to be distributed to needy families.

The committee for the 1932 Sunday School and congregational Christmas party at St John’s Lutheran Church requested that attendees bring a donation to be given to the needy. Earlier, the church’s primary Bible Classes had run a food sale with proceeds dedicated to purchasing Christmas gifts and food for the needy.

The public was urged to “buy and help encourage the young folks in well doing.” A tremendous amount of charity was done quietly over those Depression years, much of the time individuals helping to assist friends or family members who were in dire financial straits.

Even for those steadily employed, average wages were low. Workers such as farm hands, waiters, and dressmakers earned under $1,000 each year at a time when the average annual wage was estimated to be $1,368. The Fair Labor Standards Act of 1938 set the minimum hourly wage at 25 cents.

Even though the 1933 dollar had the buying power of $19.61 in 2020 dollars, enabling the fortunate few who had high wages or salaries to live well, the average American found it challenging to meet everyday expenses, especially putting food on the table.

Home grown

Family farms, still very common in 1930s Guilderland, could easily supply their owners much of their own food. Even townspeople in local hamlets and the village of Altamont often had large backyard gardens and fruit trees.

For anyone without a garden, some local farmers, themselves trying to earn some income, opened farm stands. William Hartmann set up opposite the McKownville Methodist Church; his stand was open six days a week — even evenings. In Altamont, Charles H. Britton, a Parkers Corners’ farmer, offered his “full line of fresh vegetables each day” and at “very reasonable prices.”

Other farmers such as Oakley V. Crounse sold fruit, dairy products, chickens, and eggs from their own farms. Kolenska Dairy Farm in Guilderland offered both raw and pasteurized milk and would deliver.

Come winter, fresh fruits and vegetables were a rarity, forcing everyone to turn to canned foods, either grocery-store brands or for the lucky ones, home-canned fruits and vegetables. By mid- to late summer home-canning supplies were a common feature in supermarket ads running in The Enterprise.

The Super Market offered Ball quart jars at 62 cents per dozen and pints at 52 cents per dozen, while at Central Markets prices were 4 cents for one dozen jar rubbers, 21 cents for one dozen Mason jar tops, 9 cents for a large package of parowax, 23 cents for Certo and 62 cents for one dozen quart Mason jars.

If canning pickles were on the agenda, pure cider vinegar was 17 cents (plus jug deposit) and cans of spices were 10 cents each. In 1938, The Enterprise writer from Guilderland Center noted in her column, “Vlasta Drahos is again champion canner of this vicinity. She was awarded first prize in the 4-H department of the Altamont Fair for canned fruit, for tomatoes and tomato juice and second prize for vegetables.”

“These days of thrift”

Deciding what to feed the family was made easier for housewives who could turn on their radios for food programs that offered recipes and suggestions. On WGY, there was Food Talk with Col. Goodbody, WGY Household Chats, the Radio Household Institute or the A & P program. For years, the United States Bureau of Home Economics sponsored a radio show where “Aunt Sammy” discussed housekeeping and feeding the family.

By the early 1930s, the U.S. Printing Office had produced several hundred thousand copies of Aunt Sammy’s Radio Recipes, available free to help housewives through what the government called, “these perilous times,” “these days of thrift,” “this frugal period.”

Appearing periodically in The Enterprise were menu suggestions from Ann Page, “spokeswoman” for the A & P supermarket chain. Tactfully appealing to all levels of income, here is a sample of “her” suggestions: For a low-cost dinner, serve braised lamb shanks, potatoes, mashed yellow turnip, bread and butter, vanilla pudding with preserves, tea or coffee, and milk while for a medium cost dinner the housewife could serve chicken fricassee, boiled rice, carrots and peas, bread and butter, chocolate cream pie, tea or coffee or milk. A very special dinner suggestion was cranberry and orange-juice cocktail, chicken pie, browned sweet potatoes, creamed onions, green salad, French dressing, hot rolls and butter, jelly roll, tea or coffee or milk.

Even the most self-sufficient housewife or farm wife was forced at least some of the time to shop at a local grocery store or supermarket.

Both Empie’s Market in Guilderland Center and Ward’s Store in Guilderland were affiliated with the WGY buying network, actually named after the radio station, but not connected with it. The increased buying power of this large group of independently owned stores allowed the local WGY grocers to offer weekly specials and regularly advertise in The Enterprise.

Altamont had independently-owned stores such as Hudson Food Store, Altamont Cash Market, and Pangburn’s Food Store, although they may not have all operated during the same years. Altamont Cash Market offered a pound of soup bones for 5 cents, stew beef for10 cents per pound, stew veal for 10 cents per pound, lamb stew for 10 cents per pound, and butt or shank ham ends for 22 cents per pound.

Cash Store butcher Charles Ricci was selling a pound of shoulder veal for 25 cents or a pound of veal chops for 28 cents to those who could afford prime meat. These small stores faced stiff competition from two national chain super markets, the A & P and the Grand Union, both of which had expanded their chains into Altamont

Compared to modern supermarkets, these were relatively small stores but had great buying power and were able to offer lower prices than local independently-owned markets. To their advantage, the locally-owned markets offered credit to customers who didn’t always have ready cash and they would make deliveries. Neither the Grand Union nor the A & P advertised regularly in The Enterprise.

Two Schenectady-based supermarkets did seek to attract Guilderland customers, possibly because a certain number of local people worked at General Electric or other jobs in the Schenectady area and traveled back and forth. Advertising regularly in The Enterprise were The Super Market with two Schenectady stores on Broadway and Central Market, and the two local Golub stores that grew to become the Market 32/Price Chopper chain today.

Closest to Guilderland was their store at 2600 Guilderland Avenue, touted in their ads as “most convenient if you live in or near Altamont.” “Shop the easy basket way” meant serving yourself but, if you didn’t mind traveling a few miles and had cash to pay, a budget-minded customer could snag some real bargains.

Central Market’s clever merchandising included staying open until 9 p.m. on Friday and Saturday nights and assuring shoppers there were plenty of parking spaces. Quoted in one of its 1934 ads was, “For the past year my friends have talked about nothing but Central Market and their easy prices. Now I’m talking Central, too.”

A three-store Albany chain called Trading Port also appeared in The Enterprise, appealing to McKownville folks with the slogan, “Every day a bargain day, shop and save the basket way.” Its location was 1237 Western Ave. at the city line.

Unlike the local independent stores, both Schenectady supermarkets offered prices with half cents. Central Market was selling cans of fancy pumpkin for seven-and-a -half cents, a pound of Maxwell House coffee for twenty-four-and-a-half cents and genuine Long Island ducklings for nineteen-and-a-half cents per pound.

Some samples from The Super Market were pork loin roast for eighteen-and-a-half cents per pound, a package of Grape Nuts Flakes for nine-and-a-half cents and California sardines for seven-and-a-half cents.

Dining out

Dining out was another option that families could enjoy, although restaurant dining seemed rare and few restaurant ads ever appeared during those years. Scanning the local columns of The Enterprise shows a tremendous amount of visiting among friends and relatives, often with dinner or luncheon mentioned.

For families with some spare cash, church suppers offered the dual opportunity to socialize, and to dine out at a reasonable cost. In 1932, when the Ladies’ Aid Society of St. John’s Lutheran Church put on its annual chicken and waffle supper, approximately 200 attended.

The Village Notes column pointed out, “…while the patronage fell off fully a third from last year due to current conditions, the supper was reported a success and a considerable sum of money raised.”

The coming-events columns frequently mentioned church dinners. McKownville Methodist Church, Hamilton Presbyterian Church, Parkers Corners Methodist Church, and St. Mark’s Lutheran Church all had dinners or food sales of some sort.

For 75 cents in early October 1935, you could stop by the Hamilton Presbyterian Church for a chicken dinner with chicken, biscuits, dressing, mashed potatoes, buttered carrots, cabbage salad, jello, rolls, apple and pumpkin pies, and coffee on the menu.

A few weeks earlier, the Parkers Corners Methodist Church was charging adults 50 cents and children under 12 could eat for 25 cents. The Harvest Home Supper menu: roast lamb, mashed potatoes, corn, pickles, rolls, coffee, and jello.

At times, other groups such as the 4-H and Altamont Businessmen’s Bowling League also offered suppers as well.

Like the rest of America, some of Guilderland’s families sailed through the Great Depression easily and could take advantage of the depressed prices to live very well.

Most were forced to be very thrifty to manage to eat, pay the rent or property taxes, run their car and heat their house, while there were others in our town who suffered poverty, deprivation, and sometimes malnutrition.

For most Americans, the Great Depression years were a very trying time.

— Photo from the Guilderland Historical Society

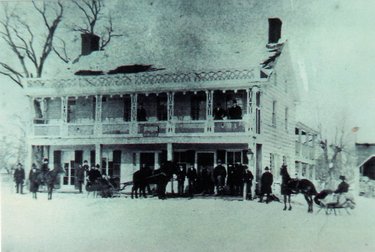

Imagine the stereographic or magic-lantern views of the coming Robbins Circus shown on the piazza of the Knowersville House (later called the Altamont Hotel). What a way to stir up anticipation in 1885! This building was set beside the railroad tracks facing Main Street. Today, a gas station and convenience store is on the site.

News in the 1880s and ’90s that a traveling circus was stopping in town created an air of anticipation and excitement among all ages. Normally, the daily lives of that era’s country folks were monotonously routine, making the novelty and glamour of the circus’s arrival an event to remember.

Advance news in The Enterprise in July 1885 that Frank A. Robbins Circus and Menagerie was about to appear not only stirred up interest in Knowersville (after 1887, the name was changed to Altamont), but in the surrounding hamlets as well. Knowersville, conveniently located on the busy D&H rail line, was the perfect spot for a one-ring circus to set up and attract paying customers from a wide area.

Using what was advanced technology of the time, the event was promoted with stereopticon views of the coming circus from the piazza of the Knowersville House. The exact location where the circuses that visited Knowersville/Altamont set up their tents and menageries was never specifically identified, but there was certainly much open land adjacent to the village at that time.

When the big day arrived, the village was packed with circus-goers “from near and far” filling village streets to view the circus parade. Circus parades were an American tradition acting as free come-ons, but the cost of admission of this or any of the other circuses over the years was never publicized in The Enterprise.

Following the Robbins’s circus parade were two performances, afternoon and evening, attended by large audiences. In the next week’s edition, The Enterprise editor commented approvingly that “it was the first time in our experience with a show of this kind in town, the program as advertised was carried out.”

Again in 1889, Frank A. Robbins Circus made a stop in Altamont, now with additional attractions including a Wild West hippodrome and a museum in addition to his circus and menagerie. Enterprise readers were advised, “Do not fail to visit this wonderful show … a good circus and an extensive collection of wild animals.”

With the arrival of the Robbins Circus, the village was described as “being in a flutter of excitement” with small boys as well as many of mature years out in force. The next week’s edition noted that the circus had come and gone except for a mound of earth in the shape of a ring … .”

Apparently the day they were leaving town, mention was made by departing circus workers that some reptiles had escaped. No one took it too seriously until one of Mrs. Wm. M. Lainhart’s family members encountered, what The Enterprise described, an “immense snake coiled up near the Old Schoharie Plank Road.”

After being alerted about this discovery, Jacob Van Auken dispatched the unfortunate serpent with an ax. When stretched out full length, it measured eight feet long, attracting many curious onlookers over the next few days.

Sad tale

Circus life in the small one-ring circuses that crossed rural America was fraught with insecurity and uncertainty. The expenses of feeding and paying performers and other workers, feeding animals, covering transportation costs, keeping up the conditions of equipment and tent, and providing a profit for the owner had to be met from ticket sales.

The visit of Rice’s Circus to Altamont proved to be one of the last chapters in the sad tale of a circus down on its luck.

The visit was scheduled for July 1887. The Enterprise announced that the advance car of J.H. Rice’s Circus and Menagerie had arrived, making preparations for a show later that week. The editor claimed, “The show is highly endorsed by the press and we have no hesitancy in speaking in its favor.”

The arrival of the Rice circus caused a stir in the village. Although the outfit had many wagons and other material, the condition of their tent was “torn and dilapidated.” Circus officials brushed it off, claiming the conditions were “due to being hit by a cyclone,” but The Enterprise’s snide comment was, “That gave them away.”

The performers carried on like troupers with the paper admitting many of the acts were “quite meritorious,” but unfortunately the audience attendance was rather small. Rice’s Circus moved on to Albany “where it was reported it was sold to Jacobs & Proctor, who give outdoor 10 cent shows.”

“The Circus Again” was an article appearing the next week continuing the sad saga and fate of Rice’s Circus after leaving Altamont. Setting up in Albany, the circus first suffered disaster when its elephant “Empress” nearly killed a circus-goer.

The circus, which had been operating at a loss, had hoped to “retrieve their fortune” on reaching Albany, but no luck. Manager J.O. O’Brien ordered a quiet street parade, no band playing, moving south out of the city, intending to head for Philadelphia.

Skipping town, leaving behind unpaid and angry creditors, the circus arrived in Coxsackie where the troupe gave a performance. They then, apparently on foot and in wagons, made it to Jersey City.

Here an employee named Edward Welch, went to court, seeking his unpaid salary and also charged “cruelty to dumb animals,” claiming the horses, camels, elephant, lion, and bulls had not been fed since they left Albany and that one of the camels died of starvation.

An arrest warrant went out for O’Brien, but, seemingly an expert on skipping town, he was nowhere to be found. The remains of his circus was moved on to Philadelphia, perhaps where it had originated.

Huge numbers of animals, both domestic and exotic, traveled with these circuses, and at that time their treatment was not an issue except among a very few. In 1907, a short article appeared in The Enterprise, illustrating concern for the poor treatment of circus animals.

“Trained By Cruelty” claimed that “animals as a rule were taught tricks through torture,” adding that some members of the circus community “speak with horror of the methods of some trainers.” Animal welfare was not an issue for most circus-goers and it was unusual to see reference to this topic in those years.

Circuses grow

One-ring circuses continued to stop in Altamont on and off for the next few years.1892 brought Chas. Lee’s Monster London Circus with acrobats, gymnasts, trapeze artists, a clown, and performing dogs and horses.

The circus was described as “strictly first class” with a “splendid street parade,” and as being “entirely free from fakirs, gamblers or other objectionable features.” Chas. Lee’s circus returned the next year with a show “better than many that charge twice the admission.”

Disreputable hangers-on or dishonest circus employees often used the honest and naïve circus-goers encountered at these rural stops as chickens ready to be plucked.

In 1908, after a visit by Frank A. Robbins Circus, an Enterprise article titled “Robbery and Flim-Flam Game” mentioned one “aged and respected citizen lost $200 to a “slick individual,” while a young man was flim-flammed out of $56 by the ticket seller.

Others were robbed of smaller amounts, making the promise of respectable behavior by circus employees in advance publicity a plus for potential customers.

In all the promotion of visiting circuses, there is never a mention of the cost of admission whether for one of the small one-ring circuses that visited Altamont or the really big shows that appeared in Albany. Certainly not everyone could afford to go to the circus, though the street parades were free for the public.

While in 1893 Sautelle & Ewer’s Circus set up in Altamont, playing to large crowds, a decade later Sautelle’s Circus was described as a “mammoth affair,” bypassing Altamont to set up in Albany. Now expanded into a two-ring circus and traveling on 26 railroad cars, there were the usual circus acts and menagerie.

New additions included the royal Roman hippodrome and a historical Wild West Show. The acts were “all new and novel and original,” many being described as “highly sensational.”

Not only was there a 63 horse and pony act, but the unique “earth’s only pony riding lion named Nero performing wonderful feats.” A mile-long street parade promised to be a brilliant pageant of lustrous chariots, dens of wild beasts, bands, a steam calliope and “more big things than ever was witnessed before in a street procession.”

Competition between the two huge circuses Barnum & Bailey and Ringling Bros. that were traveling from one large city to another forced each of them to become more elaborate each year. In turn, their shows put pressure on smaller circuses to expand or like Rice’s, be pushed into bankruptcy.

Albany and occasionally Schenectady or Troy became the setting for an annual visit of one or both of these big circuses. Hoping to attract large audiences, the circuses put out detailed publicity notices describing their new and novel attractions for that year, inserted in all the newspapers while railroads put on special excursion trains for patrons to travel at reduced rates to attend the circus.

At this stage, smaller circuses were relegated to performing in more outlying rural areas.

Using the 1912 Barnum & Bailey Circus’s publicity announcing their appearance in Albany as an example, here are the details of their fabulous show for that year. Their performance was now expanded with a cast of 1,250 characters; a grand opera chorus of 100 voices; an orchestra of 100 musicians; a 350-dancing-girl ballet; 650 horses; five herds of elephants; caravans of camels; and an entire trainload of special scenery, costumes, and stage effects.

There was to be a lengthy parade and their spectacle “Cleopatra.” The circus traveled on a train more than a mile in length and would cover 14 acres when set up.

There were 110 cages in the menagerie and over 2,000 wagons and other vehicles. This circus has nearly 1,500 employees, 700 horses, and nearly two-thirds of all the elephants in America.

Barnum & Bailey promised what you saw in Albany would be the same as the performance the audience experienced in Madison Square Garden. They guaranteed, “This is the greatest spectacular theatrical and circus event in the history of amusements in America.”

Both Barnum & Bailey and Ringling Bros. changed their spectacles annually plus added new exotic animals and acts to get audiences to return each year.

(Just an aside: With all those animals and all those people, can you imagine the unsanitary conditions left behind when the circus left town back in those days?)

Fair attractions

And what about the performers in the small fading or bankrupt circuses who didn’t have the talent or unusual act to be in the big-time circuses? By the turn of the 20 Century, county fairs were in their heyday and troupes of former circus performers found a new venue.

In 1908, Altamont fair-goers could see several free attractions including the Ethiopian Black Birds, Bilyck’s Educated Sea Lions, The Trained Chimpanzee, The Four Famous Dieke Sisters, The Double Jointed Midget, and The Famous Gila Monsters. Each year, similar attractions traveled the county fair circuit, becoming part of each fair’s attractions.

Circus-going in the later 19th Century and during a large part of the 20th Century was a popular pastime for those who could afford admission. In those times, very few ever raised concerns about the treatment of the animals or the working conditions of performers and other workers employed setting up or breaking down the circus on arrival and departure.

The free and lengthy and elaborate street parades created a spectacle for everyone. With the excitement and glamour, is it any wonder so many kids wanted to run away to join the circus and a few adults secretly wished they had?

Location:

— From the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention

Red Cross volunteers in Boston: Massachusetts had been drained of doctors and nurses due to calls for military service, and no longer had enough personnel to meet the civilian demand for health care during the 1918 flu pandemic. Governor Samuel Walker McCall asked every able-bodied person across the state with medical training to offer their aid in fighting the epidemic. Boston Red Cross volunteers assembled gauze influenza masks for use at hard-hit Camp Devens in Massachusetts.

— From the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention

Red Cross volunteers in Detroit: Motor Corps and Canteen volunteers from the Detroit chapter of the Red Cross take a break from delivering supplies to flu victims. To prepare Detroit for what was to come from the pandemic, the Red Cross and Department of Health nurses cooperated together for home visits, food preparation, and child care.

— From the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention

Open-air police court in San Francisco: As the number of influenza cases in San Francisco rose sharply, the City Board of Health issued a series of recommendations to the public on how to avoid contracting influenza including avoiding the use of streetcars during rush hour, avoiding crowds, and paying attention to personal hygiene. To prevent crowding indoors, judges held outdoor court sessions. The Board of Health recommended all services and socials be held in the open air, if they weren’t cancelled.

— From the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention

Ambulance duty in St. Louis: The Motor Corps of St. Louis chapter of the American Red Cross was on ambulance duty during the influenza epidemic in October 1918. The Red Cross motor corps recruited volunteer drivers and automobiles to supplement ambulances and chauffeur nurses from one quarantined house to the next. Through this volunteer system, approximately 40 nurses cared for about 3,000 patients who otherwise had no access to private nursing.

The normally pleasant days of late summer 1918 were overshadowed by an outbreak of Spanish influenza, initially affecting a naval training base near Boston, next a nearby army camp, then rapidly infecting Boston’s civilian population. Quickly reaching epidemic proportions and spreading out along the nation’s rail lines, wide swaths of the country were soon overwhelmed by the disease.

The disease originally surfaced in Spain in February 1918 as a somewhat milder form of influenza with widely scattered outbreaks over the summer, only to erupt in a second wave during the last weeks of August in a more contagious and virulent form. Not only was there a high death rate among the very young and old, unusually, a high mortality rate affected otherwise healthy 20- to 40-year-olds.

A tragic coincidence was, in late August, for the fifth year, World War I was raging in Europe. A huge military build-up had begun in this country after our declaration of war on Germany in 1917.

Since the United States had virtually no army at that time, training camps were immediately established, each housing 25,000 to 50,000 men — both volunteers and draftees — often crowded over capacity. Once training was complete, jammed troop trains transported the men to ports to be shipped to European battlefields in close quarters on troop ships, a perfect scenario for spreading the influenza virus.

Among these troops, there were many men from Guilderland and the surrounding area.

Local life as usual

As usual, life was good for most of Guilderland during August that year. Those fortunate enough to own an automobile were out on motoring trips. Others stayed close to home, visiting friends and relatives, attending church services, or socializing at meetings or events like the ice cream social at St. Mark’s in Guilderland Center.

However, it was noted in that community’s Enterprise column that, during the last week of August, five women were ill, though with no details. Otherwise, life seemed normal.

Endless local events were on tap to make September a very busy month. The Altamont Fair ran from Sept. 17 to 20 that year, on one day attracting 10,000 people. Guilderland voters gathered at the polls on Sept. 14 to vote on the local option to turn the town “dry.” A large turnout, including newly enfranchised women, cast their ballots at the only polling place at the town’s recently acquired building in Guilderland Center.

School openings, numerous church services and activities, meetings of Red Cross groups, family reunions, Saturday night movies at the Masonic Hall, the usual social calls all led to an amazing amount of social interaction among town residents. But only the Guilderland Center and Parkers Corners columns mentioned illness, again nothing specific.

However, in nearby Albany, influenza cases suddenly spiked during late September and it’s very likely many cases had begun to crop up in Guilderland unannounced in the local columns.

Most newspapers, whether weeklies like The Enterprise or city dailies, gave limited coverage of the epidemic, which by mid-September was raging not only in Boston or Philadelphia, a city that was particularly hard hit, but also in smaller cities like Albany where, by early November, 7,091 cases were reported.

Freedom of the press was limited during World War I. Federal legislation forbade any reports critical of or disloyal toward the government, anything unpatriotic, or anything that would hurt the war effort. Stiff penalties could be imposed. Papers tread carefully, fearing too much news about the epidemic would have a bad effect on morale.

Albany’s Health Officer seemed to believe it was not a serious epidemic, forcing Dr. Herman Biggs, the New York State Health Commissioner, to issue a letter to newspapers of the state on Sept. 27, 1918, asking them to warn their readership “to brace for the epidemic.” He also requested that physicians report cases of influenza and pneumonia in their locality. This message did not appear in either of the next two weeks’ editions of The Enterprise although anyone who read an Albany daily surely would have been aware of it.

Guilderland readers took notice on Oct. 4 when, at the bottom of The Enterprise’s front page, a report of a Coeyman’s soldier’s death from influenza and pneumonia appeared. That fall, he was the first of local soldiers in our immediate area to die of influenza rather than war wounds.

That same edition of The Enterprise reported that Earl Becker, stationed at the naval recruiting station in New Haven, Connecticut, came home to Altamont on a 48-hour furlough, and, having contracted Spanish influenza on his way home, was quite ill. He fortunately recovered and returned to duty.

Otherwise in Guilderland, that first week of October life went on as usual. At the Masonic Hall, a traveling stock group performed a different play each night for five successive nights, attracting large audiences. Church groups and fraternal organizations met, church services were held, and children attended school. Only the Dunnsville and Guilderland Center columns reported a small number ill, but with no mention of influenza.

Hit with a vengeance

The disease hit town with a vengeance during that week because, by the time the next week’s Enterprise was in the hands of readers, churches and schools had closed. At the bottom of page one, a short notice stated that, at the request of the Board of Health, no public gatherings could take place in Altamont for several days.

“Both of the churches will be closed all day Sunday, the movies, lodges, prayer meetings, Sunday Schools and society meetings will be discontinued on account of the prevalence of the Spanish influenza which has made its appearance here,” The Enterprise reported. According to the notice, only a few cases had been reported in the village and it was thought these rules would help to halt the spread of the disease.

Page five of the same edition carried a brief notice from the Surgeon-General of the United States Public Health Service that he had issued a publication dealing with the Spanish influenza, which contained all known available information regarding the disease. Anyone interested could send for the publication by mail.

In the meantime, there were already thousands dead in East Coast cities such as Philadelphia, New York, and Boston. In 1918, the federal government was not very involved with national health issues but, as the situation worsened, the Surgeon-General sent out a communique to newspapers across the nation.

Prominently headlined atop page one of the Oct. 18 Enterprise was: “Uncle Sam Gives Advice on the ‘Flu’” with the warning that “droplets” from sneezing, coughing, or even hardy laughter could infect others. It was the local officials, however, who actually stepped in to take action to prevent the spread of the disease and, in urban areas, also dealt with the huge number of deaths.

At this time, Guilderland Center’s correspondent reported, “The epidemic of grippe (the old-fashioned word for influenza) is so prevalent in our village there is scarcely a home which has not had someone ill.” Church services were cancelled as were meetings of the Red Cross, Christian Endeavor, and Sunday School lessons. The Liberty Bond Drive meeting with its out-of-town speaker also had to be cancelled because the speaker had the disease.

Although several McKownville residents had been stricken, it didn’t stop that community’s baseball team who “rung down the curtain on the season” with a dinner at Albany’s Keeler’s Restaurant. This must have taken place before Oct. 9 though, because the epidemic had become so critical in Albany that on that date everything was shut down as cases there mounted into the thousands.

Another complication of our involvement in the war was that, out on the Western Turnpike in Fullers, there were two couples under the care of Voorheesville’s Dr. Joslin. During October 1918, about 38,000 American doctors were either serving overseas — such as Guilderland Center’s Dr. Hurst — or at military training camps, placing an additional burden on the doctors remaining at home.

It was reported that, in one day that October, Dr. Joslin treated 58 influenza cases, obviously traveling far afield if he were paying house calls from Voorheesville over to Fullers.

Numerous names of influenza sufferers are mentioned in the various Enterprise columns from all parts of town, but the progress of one case described repeatedly was that of Millard Cowan, a well-known Altamont resident first reported suffering from influenza in the Village Notes column Oct. 25. He was under the care of Dr. Cullen and a trained nurse.

A week later, even though it was cited that the epidemic of influenza in Altamont had practically ceased to spread, the most serious case was Millard Cowan, “critically” ill for more than a week. Developing pneumonia as a complication, “for several days his life was in the balance. We are now informed that hopes are entertained of his recovery although it will be several days before he is out of danger of a relapse.”

The next week, Cowan was slowly recovering. “Of the many cases in this vicinity, Mr. Cowan’s was the most serious of all,” the columnist wrote. It was predicted he would be around again in a few weeks’ time.

Another week later, he was “recovering very nicely,” the columnist wrote, noting it was four weeks ago Thursday that he had come down with the illness. His nurse, Miss Hadley, left Monday, seeing he was considered out of danger. Thursday he sat up for the first time.

Cowan didn’t return to his job in Albany until the second week of January. In the meantime, his wife had received the tragic news that her brother on duty with the army in Europe had died of influenza and pneumonia.

Schools close

Schools closed at various times in various parts of town. Those that were noted suspending classes were Guilderland Center, Guilderland, Dunnsville, Meadowdale, Parkers Corners, and Fullers. Altamont’s school, which housed grades one through twelve, closed on Oct. 14.

Dr. Cullen ordered Altamont’s school to remain closed even though other activities in the village were allowed to resume. After three weeks, the school was permitted to reopen, but grades one and two and grades five and six (at that time two grades to a classroom) were dismissed on Tuesday for the remainder of that week due to sickness. Even Prof. Hook, the high school principal, had had the flu.

Flu kills soldiers

Into early November, Guilderland was fortunate that, while much of the population had had the influenza, there seemed to have been no fatalities here. However, it was reported in the Nov. 8 Meadowdale column that “a telegram was received here Saturday stating that Matthew Hennessey was seriously ill at Camp Wheeler, Ga.”

The next week, word came that Harry Mesick of Altamont “who was inducted into service about three weeks ago and sent to Camp Wheeler, Ga. with a number of other young men of this vicinity, was taken sick shortly after arrival, died last week. His body was buried near the camp. His sudden death came as a shock to his friends here, who deeply sympathize with his family.”

The next week, news came that “Matthew Hennessy died on Tuesday, November 5 at a base hospital in Georgia, age 21 years. His funeral was held at St. Matthew’s Church.” These two men and the Coeymans soldier were among the 43,000 servicemen who died in the influenza pandemic, more than the number of Americans who were killed in battle during World War I.

Winding down

During the month of November, there were still many local cases of influenza reported, but the number seemed to be winding down. December brought virtually no reports of new cases.

However, in January 1919, there were many new cases. Settles Hill farmer Walter Gray died early in the month. and a few weeks later Clarence Osterhout, age 34, died at his home in Altamont after being ill less than a week.

Then, the numbers dropped and by spring Spanish influenza seemed to have disappeared from town.

To this day, the actual origin of Spanish influenza isn’t definitely known — certainly not Spain. Some researchers claim China; others theorize it all began in Kansas.

Estimates run as high as 50 million people or more who died worldwide; of those, 675,000 were Americans. While Albany suffered over 450 deaths, Guilderland’s comparatively low mortality rate — and it’s possible there were additional deaths not listed in The Enterprise — was probably due to its rural character and cancellation of activities.

Location:

The Enterprise — Marcello Iaia

Clayton Ogsbury’s gilt-framed portrait hangs at Enterprise Printing and Photo at 123 Maple Ave., long the home of The Altamont Enterprise, which has since moved across the street to 120 Maple. Clayton Ogsbury was the brother of John D. Ogsbury who had owned The Enterprise.

Newly discovered veins of gold and silver in the western territories attracted hordes of fortune seekers in the years immediately following the Civil War. Joining the exodus west was David Clayton Ogsbury, a 22-year-old who had grown up with his brothers and sister on the Settles Hill farm worked by generations of Ogsburys since the 1790s.

Feeling there was little future for him in this area, the adventurous Clayt decided to relocate to the Colorado Territory in 1869. Before boarding the Albany & Susquehanna train at Knowersville, he made his goodbyes to his parents, brothers, and sister. Rev. William P. Davis, pastor of the Helderberg Reformed Church where Clayton had always attended services, had also come along to wish him godspeed.

Denver, Clayt Ogsbury’s new home, had become a bustling town within a few short years of its founding. Quickly obtaining employment, Clayt Ogsbury began to invest in mine shares. A few years before, gold and silver discoveries in the mountains of southwestern Colorado had led to the establishment of several small settlements in that area.

Rumors of rich silver lodes supplying amounts as much as 500 ounces per ton had reached Denver, inspiring the ambitious young Clayt Ogsbury to relocate to the rough mining town of Silverton, a community high in the mountains, reachable only by trails, some years cut off for months by heavy winter blizzards.

In 1877, before the winter snows blocked the mountain passes, Clayt returned to Denver where he began the rail trip east to visit his childhood haunts around Knowersville. He reconnected with family and friends, bringing with him a souvenir, an engraving of Silverton and the surrounding mountains.

Drawn from a recent landscape painting, the print would enable everyone back in Guilderland to visualize the spectacular scenery and mining operations of his new home.

On his arrival, family and friends, delighted to have him back in their midst, found a mature, self-confident, successful man, who impressed everyone with his demeanor. Assuring his father that he was now quite prosperous, Clayt promised to pay off the mortgage on the Ogsbury farm, handing over several gold nuggets to his elderly father with the promise of more to come.

The first documentary evidence of his residence in Silverton was a liquor license dated 1879, a common way to make a living in a mining town of that period. During the next two years, Clayt was also mining some claims in nearby Ophir with the colorful names of Little Dora, Empire, Cocktail, and Ajax.

Ogsbury named marshal

In Silverton, his reputation of being a sober, hardworking, responsible man of integrity led to his being named in 1880 as court bailiff. A year later, on May 9, 1881, Clate (as his name was always spelled in Colorado) Ogsbury was appointed town marshal of Silverton.

Almost immediately, he made his first arrest, a fugitive robber on the lam from another county. At the same time, he continued his mining ventures with a new claim called “Crown Jewel.”

Silverton in 1881 was a typical western mining town, its main street lined with a mix of saloons, dance halls, and gambling dens frequented not only by the locals, a rough bunch in themselves, but also by tough hombres passing through. The Diamond Saloon was perhaps the most disreputable of the lot, offering drinks and dancing with the “ladies” employed there, all under the watchful eye of “Broncho Louisa.”

An unsuspecting patron, unaware that the usual customers were the roughest element in the town, complained to Marshal Ogsbury after discovering he had been stripped of all his valuables. The marshal promptly arrested “Broncho Louisa,” who, after spending a night in jail, soon made her outraged feelings known to the regulars at her saloon.

By coincidence, riding into town late that same day were Burt Wilkinson, Dyson Eskridge, and an African American known as the “Copper-Colored Kid” — three cowboy members of the notorious Stockton-Eskridge gang. All three had a price on their heads, the result of misdeeds in Durango in a nearby county.

The Copper-Colored Kid was also wanted in Texas, where a $1,200 reward had been posted. First stabling their horses in a livery stable several blocks up the street, the three headed for the toughest dive in Silverton, the Diamond Saloon where the angry clientele was still seething over Marshal Ogsbury’s treatment of their “Broncho Louisa.”

Early on the evening of Aug. 24, 1881, Luke Hunter trotted into Silverton. He was the sheriff of La Plata County, where Durango is located, and he carried warrants for the arrest of Wilkinson, Eskridge, and the Copper-Colored Kid.

This man of no integrity and little courage let all and sundry know that he had the warrants, most likely to warn the outlaws to hightail it out of town, sparing him any unpleasantness. However, the action at “Broncho Louisa’s” must have been just too good because the three gang members decided to stay put.

Shot in the line of duty

When Hunter went to find Ogsbury to inform him of the warrants, the marshal wanted to get additional backup, but the sheriff, who may have thought the three outlaws would be gone by then, insisted that there would be no problems.

Hunter, Ogsbury, and a man named E.W. Hodges began to walk down Silverton’s main street. Approaching the Diamond Saloon, Ogsbury became aware of a man lurking in the shadows. As he peered to get a better look, there was the explosive sound of a shot.

Ogsbury crumpled, falling face forward with a bullet lodged just above his heart. When Hunter and Hodges turned Ogsbury on his back, he groaned. But as more shots were fired from the saloon, they quickly retreated without ever returning fire. Clayt Ogsbury died in the dusty street.

Cut off from their horses at the livery stable down the street, the three desperadoes fled on foot and were able to get out of town without having one shot fired at them. A short time later, they sent the Copper-Colored Kid back into town to retrieve their horses, but he was quickly captured, arrested, and put in jail.

The next evening, angry locals stormed into the jail, “overpowered the jailer,” and lynched the “Kid” in his jail cell. The local newspaper later reported the incident in racist terms.

Clayton Ogsbury’s funeral was attended by 500 people. Afterward, his body lay in state in the courthouse for several hours and then a huge procession followed it to the cemetery. All of Silverton’s businesses had closed in his memory.

That very day, a telegram arrived from Dunnsville, New York with Ogsbury’s family requesting the return of the marshal’s body. It was disinterred, embalmed, and the coffin taken over mountain trails to the nearest railroad to begin the long journey home, accompanied by Rev. Harlan Page Roberts, the minister of Silverton.

With the common belief in Silverton that Burt Wilkinson was Ogsbury’s killer, reward money reached the sum of $4,000 for his capture. Wilkinson and Eskridge had escaped, hiking on foot, finally getting shelter at a friendly ranch.

Ike Stockton, leader of their gang, had no qualms about “arresting” Wilkinson and turning him in for the reward money. Within 24 hours after being jailed, the locals “overpowered the jailer” and as they had the Copper-Colored Kid,the locals hanged him in his cell.

At about the same time, in early September, a solemn crowd of over 100 people gathered along the D & H tracks by the tiny Knowersville depot, waiting to pay their respects as the train carrying Clayton Ogsbury’s coffin pulled in.

The Helderberg Reformed Church was packed to capacity the day of his funeral when Rev. H.P. Roberts of Silverton, assisted by the church’s pastor Rev. Samuel Gamble, led the service. After the funeral, the crowd followed the coffin across the road, climbing the hill to the cemetery for burial. At his gravesite a stone was later erected with a carving of his marshal’s badge prominent on top where it stands to this day.

Settling his estate

In October 1881, J.H. Ogsbury and John Ogsbury, Clayt’s father and brother, showed up in Silverton to settleClayton’s estate. According to the San Juan County Historical Society’s archivist writing in 1986, the estate records are incomplete.

According to the late Arthur Gregg, Guilderland’s town historian, Ogsbury’s father had delayed going west until spring. When he went to Silverton, he took with him a “country justice of the peace” who was not competent to deal with the complexities of mining claims. Clayt’s father received only a few gold nuggets and enough from a bank account to pay off the mortgage on the Ogsbury farm.

Arthur Gregg would have known both John D. and his son, Howard, very well and would have gotten family information from them. Ogsbury family members claimed it was an incompetent lawyer (who very well may have also been a justice of the peace) because there should have been rich mining interests as part of this estate.

With the amount of lawlessness in that area at that time, it is very likely Clayton Ogsbury’s mining interests were taken by someone else before his family had a chance to establish their claim, losing out on what could have been a fortune.

John D. Ogsbury, Clayton’s brother, became the owner of The Altamont Enterprise and hung Clayton’s photograph and the engraving of Silverton that Clayt had brought with him when he visited in 1877 on the wall where he could see it as he worked at the press and where they remain to this day, a memorial to a man who died doing his duty.

Location:

— Photo from the Guilderland Historical Society

St. Mark’s Lutheran Church, dedicated in 1872, was located on Guilderland Center’s Main Street. Several times a year, it was the scene of the dinner where a radio broadcast was the draw to bring in a large crowd. Today the church is Centre Point Church.

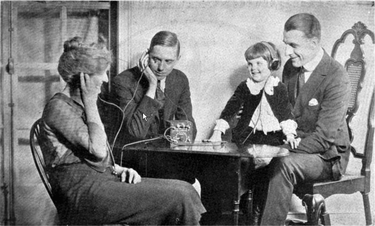

— Radio World Magazine, 1922

From a 1922 advertisement for Freed-Eisemann radios, an American family listens to a crystal radio. Since Crystal sets work off the power received from radio waves, they are not strong enough to power loudspeakers. Therefore the family members each wear earphones, the mother and father sharing a pair.

Radio first became a reality for the general public in November 1920 when Westinghouse station KDKA in Pittsburgh went on the air; its first broadcast was the news of Warren G. Harding’s electoral victory in that year’s presidential race.

General Electric in conjunction with the Radio Corporation of America launched Schenectady’s WGY in February 1922. Bitter competition existed between the two corporations, each intent on cornering the radio market to sell equipment to the millions of people eager to listen to this exciting new form of entertainment

Eventually GE and RCA made an agreement with Westinghouse to take over Westinghouse’s superior wireless patents in return for General Electric stock.

Having a powerful radio station nearby was the incentive for Guilderland residents to join in the national craze for radio. The Altamont Enterprise, recognizing local interest in the novelty, quickly added WGY’s weekly schedule to its pages.

Soon after, when the editor queried readers on the schedule’s value, he got a quick positive response, making it clear they appreciated knowing what was on the air that week. One Altamont listener felt, “It’s worth the price of The Enterprise to have this feature every week.”

The Guilderland Center columnist noted, “So many have installed radio outfits in their homes, and are glad indeed of the convenience of the weekly program. This is indeed an attractive feature of The Enterprise. Thank you, Mr. Editor.”

The popularity of radio spread so rapidly across the country that, by the end of 1922, WGY was one of almost 350 stations. Americans spent $60 million on radios and radio parts in 1922 and, by 1924, sales reached $358 million.

Radio purchasers were sometimes mentioned in local columns. Guilderland Center’s John J. Mann and Earl House, Altamont’s Walter Gaige, Guilderland’s Charles DeCoursey, or Dunnsville’s Charles Crounse and Jacob Becker, all installed radios along with the many others who were nameless.

The women of Altamont’s Colony Club devoted one of their sessions to the “up-to-date” topic of radio with presentation of talks on the history of radio and the topic “forecasts on broadcasts.” Entrepreneurs jumped on the bandwagon and began selling radios and radio parts and accessories, often advertising in The Enterprise.

The Enterprise also installed radio equipment to enable the newspaper to keep the community informed of important breaking events. The 1922 World Series could be heard at the Enterprise office as well as at the Altamont Pharmacy.

The Enterprise “Village and Town” column explained that the sporting editor of the New York Herald would be at the Polo Grounds reporting the games by Western Union wire to WGY’s wireless station in Schenectady, which then would be broadcasting the action to its listeners.

At Christmas that year, The Enterprise planned to use the apparatus to tune into the Santa Claus talks scheduled to begin on WGY on Dec. 18.

Generous Dr. Cullen

Dr. Archie I. Cullen, Altamont’s family doctor for many years, was a serious radio buff affluent enough to indulge in his passion. “Village Notes” told of his wireless apparatus being damaged by gale winds, when six feet of one of his 60-foot masts blew off. The doctor assured folks it was easy to repair since the mast was constructed to be raised and lowered.

Generous with his equipment and expertise, Dr. Cullen several times provided radio entertainment for others. The big attraction at Guilderland Center’s St. Mark’s Lutheran Church’s 1922 Memorial Day dinner was not the chicken, but the opportunity to hear a WGY radio concert broadcast with Dr. Cullen’s equipment and loud speaking horn.

Three hundred and fifty people turned out including a big crowd from Altamont. A short article the next week titled “Radio Entertainment” describing the evening commented, “This is the first entertainment of the kind the church has ever given and the first of the kind that most people have ever had the privilege of listening to.”

On another occasion, Dr. Cullen and another man spent hours setting up his radio outfit to allow Sunday School youth from Altamont’s Reformed Church to hear a program of music and vocal selections and a talk. That same spring, the Altamont Alumni Banquet attendees ate their dinner to music thanks to Dr. Cullen’s “receiving outfit.”

Altamont’s Leo E. Westfall and Stanley Barton were among 300 radio enthusiasts who drove to Union College where they attended the Capital District Radio Convention and banquet. Included in the program was a trip through GE’s radio department. Lester Sharp of Parkers Corners went to work in GE’s radio department early in 1923.

Two types of early radios

Actually, how did early radios work? There were two types, neither of which needed an outside power source.

In 1922, the United States Bureau of Standards released a publication called “Construction and Operation of a Simple Homemade Radio Receiving Outfit” detailing how any handy person could put together an inexpensive crystal set from materials easily obtainable, allowing even those of relatively modest means to join listeners across the country. Less than $10 bought all the components.

The late Everett Rau shared his memories of owning and operating a crystal set in his boyhood. Many years before, scientists had discovered that a crystalline mineral such as galena could pick up radio waves.

Everett recalled that the crystal was the size of a kidney bean. He said that you placed it in a conductive container with a wire connected to it and a circular object — oatmeal containers were very popular for this — around which you wrapped anywhere from 100 to 300 feet of insulated copper wire.

An antenna was needed as well. Everett mentioned his brother ran a wire out of the house and put it up a tree, but he found his metal bed springs served the purpose just as well.

In order to actually hear the broadcasts, you had to listen through a set of earphones with a wire that ran to a pin in the crystal. In most cases, a crystal set was capable of picking up broadcasts only 25 to 30 miles away, but on occasion was able to bring in a station from quite a distance.

Those who were more affluent could purchase and have installed more expensive radios that operated on battery power. Headphones were required, but it was possible to purchase loudspeaker horns that projected the sound into a room.

The Albany Radio Corporation advertised, “We have sets for every purse and every purpose from $5 to $1,000.”

Recharging batteries was a necessity, which a Clarksville garage advertised it could do. Probably other local garages did as well. One reference said radio batteries were interchangeable with car batteries and could be recharged by switching batteries, but that couldn’t be confirmed.

A 1927 Sears catalog offered a variety of radios with one price cash and a higher one if bought on installment. One example was $59.95, or $9 monthly for $65.95. Perhaps the craze for radios was one of the earliest examples of American consumerism.

Programs varied: Music, news, drama

Tuning into WGY brought a variety of programs. Music was extremely popular, introducing many people to classical music not only locally, but all over the United States.

One WGY piano concert featured works by Chopin, Brahms, and Liszt. WGY had its own orchestra and sometimes broadcast concerts from outside its studio.

One in 1922 originated from Union College and another came from Chancellor’s Hall in Albany where a huge chorus sang to an audience including Governor Al Smith. Vocal music was performed by sopranos, baritones, and tenors.

One night there was popular music, a program of old favorites, including ”On the Sidewalks of New York” and “In the Gold Old Summertime” while the orchestra played “Turkey in the Straw” and “When You and I Were Young, Maggie.”

Drama was another important phase of programming with either the WGY Players performing or sometimes a local dramatic society was brought in. One evening, a troupe of Troy’s Masque Community Theatre put on “The Wolf.” The first year on the air, the WGY Players acted in 43 plays with titles like “The Traveling Salesman” and “The Great Divide.”

Local talent was also featured. Altamont pianist Miss Margaret Waterman made two appearances, generating letters of praise from states as far away as Kentucky, Iowa, and Montana. Magdalene Merritt, poet of the Helderbergs, read a children’s story she had written called “The Gnome of the Evil Eye.”

Educational specials brought intellectual topics to many people who had never gone beyond eighth grade or read a book. One week in January 1923, for example, there was exposure to Japan in an evening of travelogues and music, and another where a full-blooded Quiche Indian would speak in his native tongue. His spoken language had aided archeologists in interpreting Mayan hieroglyphics and the program included a talk about Mayan civilization.

Health reports, special programs for housewives, weather reports and crop prices for farmers, correct time and church services were all presented on the air. Protestant church services prevailed, but there was also a concert of Catholic Church music sung by a 75-member choir originating from Our Lady of Angels Church in Albany and a New Year’s service from Temple Beth Emeth.

One man wrote to WGY from Trumansburg, a small town near Ithaca, that the Sunday service from Trinity Lutheran Church in Albany had been a comfort to his dying father. WGY generated regular press releases like this, sending them out to local newspapers with the hope they would be reprinted.

Public service

Service to the public was another feature that stations wanted to promote.

WGY was in the middle of a news story that made national headlines in 1923 when the 6-year-old son of Dr. Alexanderson, GE’s famous engineer working the field of radio and later TV, was kidnapped.

With no clues or leads, police were stymied until a man living in a tiny town outside of Watertown in Jefferson County picked up a WGY broadcast on his crystal set discussing the case. He remembered renting a camp to a couple with a young boy. Becoming suspicious, he took his boat out to the camp and managed to get a look at the boy.

Seeing a photograph of the lad in the Syracuse paper, he knew that boy was the kidnapped child. He called the sheriff, the boy was rescued, and his kidnappers were under arrest.

The coming of radio broadcasting changed Guilderland and America by broadening the horizons of millions of people and creating a national audience. Because a crystal set was so inexpensive and listening in was free, lack of wealth was little handicap. The intelligent programming of radio’s very early days gave way to soap operas and Amos ’N’ Andy, but that was another decade.

Location:

— Photo from the Guilderland Historical Society

Wm. D. Frederick’s Center House in Guilderland Center was typical of small rural hotels with a bar providing most of his profit. His 1887 account book, now at the Mynderse-Frederick House, shows that additional income came from the sale of cigars and tobacco. The entrance to Park Guilderland is on the site today.

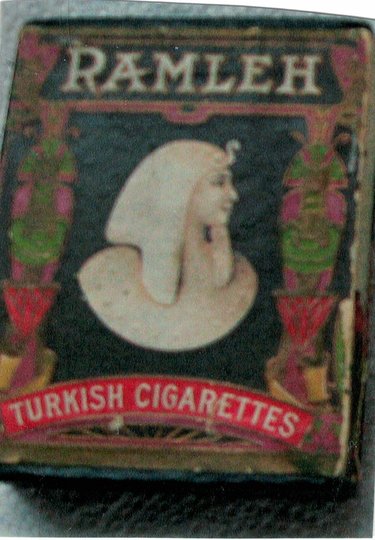

— Photo from Mary Ellen Johnson

Ramleh Cigarettes came in a beautifully colored box and was produced until 1911 when the name was reversed to Helmar because the name of a competing brand of cigarettes sounded too much like Ramleh. Joe Gaglioti, Altamont’s barber, advertised Helmar cigarettes for 15 cents a pack in 1921.

Tobacco has been a feature of American life ever since it was introduced to Europeans in the late 15th century. When presented to King James I in 1604 his judgment was: “hatefull to the Nose … dangerous to the lungs” with a “blacke stinking fume … .”

Unfortunately, most men found tobacco use a pleasurable habit, whether smoked, chewed, or inhaled as snuff. During the colonial period, it was known to be used in the Albany area, but we cannot document its presence in what became Guilderland during those years. However, by the end of the 18th Century, written references begin to surface.

The late town historian Arthur Gregg reprinted portions of old account books that he had the opportunity to examine. In the 1790s, Mr. Frederick Crantie (Crounse) listed among other items “9 lbs of sn’ff” and on another occasion 16 shillings for tobacco.

When the old Severson Tavern building was about to be demolished in the 1950s, Gregg got a look at Severson family papers. The tavern, once a busy stopping place on the Old Schoharie Road at the foot of the Helderberg escarpment (now the site of Altamont’s Stewart’s Shop), was run by Jurie Severson who kept careful accounts.

In 1813 to 1814, transactions included selling Jess Secord a “segar” for one pence, Mr. William Gardner segars for six-and-one-quarter pence, Mr. Lot Hurst a segar for one cent, and segars to Nad Groat for five-and-one-quarter cents.

Note that, in the early days of the Republic, English and American denominations were used interchangeably. Also among the Severson papers were recipes for medical treatments and among them was one for fever sores that included tobacco as an ingredient.

After Jurie Severson’s death, his son George continued to operate the tavern, recording in his account book at various times: snuff, 7 Spanish segars, and 2 lbs tobacco.

Another of our early town historians, William Brinkman, mentioned an 1816 account book probably kept by a merchant in Dunnsville who recorded the sale of ½ lb Pigtale, an early form of tobacco.

Civil War soldiers were fond of tobacco. Abram Carhart was a Guilderland recruit in the 177th New York Volunteer Infantry, a regiment assigned to the area of the Mississippi. His diary is now at the Mynderse-Frederick House in Guilderland Center. On May 16, 1863, Carhart recorded selling A. Fox, who promised to pay when back in camp, some tobacco for 5 cents, and two days later, sold to Billy (last name illegible) some tobacco for .50 cts. Shortly after, the unfortunate Carhart accidentally drowned in the Mississippi River.

Once The Enterprise began publishing in 1884, it becomes possible to survey tobacco’s use in our town through its local columns, ads, editorial content, fiction, humor, and articles. Among many Guilderland males, similar to American men in general, tobacco had a place in their lives.

Tobacco use among 19th-Century women in the Northeast was very rare until cigarettes became common in the 20th Century, and only in the 1920s do women begin to smoke in great numbers.

The earliest tobacco ads in The Enterprise were tiny one-line fillers mixed in with other information or listed in a weekly column called “Business Locals.” Men were urged to “Smoke the Pride of Knowersville, 5 cent cigars., “Try Gallop and Johnson’s Augusta 10 cent cigars,” or try “Old Honesty Cigars” manufactured by C.F.Dearstyne, an Albany firm.

These were only samples of many other cigars named. These and other one-line cigar notices pop up week after week. Later in the 1890s, some of the cigar ads were larger with the cigars actually pictured.

Male bonding

Through the newsy local columns between 1884 and the entry of the United States into World War I in 1917, cigar-smoking men were mentioned, especially on occasions of male bonding and jolly fellowship, reflecting the popularity of cigars during that period.

“Hornings” seemed to be a common masculine custom occurring either when the new bride and groom arrived home from their wedding trip or many times immediately after the wedding celebration itself. The couple could expect the local fellows to turn up making lots of noise as they did to D & H Conductor Gilroy and his bride when the guys treated them to an “old time serenade with the band being out in full force with drums, horns, guns and every conceivable noisemaking instrument.”

The raucous visitors were “thanked heartily with cigars.” Repeatedly, descriptions of hornings from all over Guilderland mention that cigars were passed out to the male noisemakers.

Male bonding was definitely the order of the evening after an 1895 meeting of the Altamont Hose Company when Mr. H. Van Schoick treated “the boys who used the weed with cigars from a ‘unique’ [quotations in the original] server, which we dare not say were the less enjoyed because of the manner in which they were ‘set up’.” We’ll just have to use our imaginations on that one!