— Photo from the Guilderland Historical Society

At the turn of the 20th Century, a popular form of snobbery for wealthy individuals was to call their mega-mansion summer homes “cottages.” Even though John Boyd and Emma Treadwell Thacher were a childless couple, they had many nieces and nephews including one who was named John Boyd Thacher II. This may be the reason that a large addition was added to the rear when they purchased the “cottage” in 1900.

For decades in the late 19th and early 20th centuries, late spring and early summer warm weather’s return brought several wealthy, prominent Albany families to the escarpment above Altamont to reopen their summer “cottages.”

Well known in their day, these affluent summer residents are long forgotten except for John Boyd Thacher whose name is attached to the nearby state park, although few know why or who he was or are aware of his association with Altamont.

A very wealthy man, Thacher’s affluence was derived from Thacher Car Works, founded in 1852 by his father in the north end of Albany. Manufacturing wheels for railroad cars including the New York Central System was a huge and very profitable business. As his father aged, Thacher and his brother became actively engaged in running the company.

Political involvement came next, a natural since Thacher’s father had served as Albany’s mayor during the Civil War years and after. A Democrat, John Boyd Thacher was first elected to the State Senate in l883 where he introduced legislation to construct a new capital building for one million dollars.

Next, he served as mayor of Albany in l886 when he organized a grand celebration on the occasion of the bicentennial of Albany’s city charter. After his term of office ended in l888, his involvement with politics continued as president of the New York State League of Democratic Clubs. He served a second term as Albany’s mayor in l896.

Attracting international attention, the Columbian Exposition, held in Chicago in l893, was a huge world’s fair attended by large crowds. Thacher became widely known when New York Governor David Bennett Hill appointed him to the commission to organize the New York State exhibit. He was also named national chairman of the awards committee for the exposition.

Interest in historical scholarship and research was another aspect of John Boyd Thacher’s personality. A discriminating collector of autographs, historical documents, manuscripts, and papers relating to the French Revolution, he was well known for his collection of l5th Century printed first editions called incunabula.

Much of his collection was donated after his death to the Library of Congress. In addition, he was the author of books on Shakespeare, Christopher Columbus, and a volume describing the evolution of maps depicting America during the early years of exploration. He made several trips abroad to do original research. At the time of his death in 1909, Thacher was in the midst of writing a book about the French Revolution.

Time in the Helderbergs

In the 1890s, John Boyd Thacher and his wife, Emma Treadwell Thacher, had begun to spend time in the Helderbergs above Altamont, their presence sometimes mentioned in The Enterprise. The date of his first visit isn’t known although an 1895 comment in The Enterprise noted that “John Boyd Thacher who has been spending the summer on the mountain near the village, has been nominated by the Democrats of Albany for mayor.”

An 1897 Enterprise article, “A Serious Runaway,” noted that John Boyd and Emma Treadwell Thacher had stayed “at the white cottage near the Kushaqua Hotel for the past several summers when describing a terrible accident involving a team belonging to Altamont liveryman Peter Hilton.

Just as Hilton was about to load some of Thacher’s luggage, the horses bolted, the runaways wrecking a buckboard owned by Judge Rufus W. Peckham, seriously injuring his two employees, and minutes later resulting in the death of one of Hilton’s horses. Thacher generously offered to pay for the buckboard, though no mention was made of the liveryman’s horse.

In November 1900, a news item reported that Thacher had purchased the late Paul Cushman’s summer home visible from the Kushaqua. Paul Cushman, an Albany merchant, had built the cottage in 1893, but sadly died there during the summer of 1895.

Thacher hired Albany contractors Feeney & Sheehan to do carpentry work on both the interior and exterior including the addition of a large extension. George Weaver, an Altamont mason, was employed to do the stonework.

In addition, Thacher intended to cut a private road beginning on Helderberg Avenue opposite Hellenbeck’s furniture store (now Fredendall Funeral Home) running up the gulch to his new home. Land had been purchased from George Severson for this purpose.

Altamont benefited economically from the demands for goods and services made by Thacher and other members of the summer colony above the village. Liverymen Peter Hilton and others were in demand to move people including the Thachers and their luggage for trips up and down from the depot before the automobile came into use.

Later Peter Hilton (though this may not be the same man as the liveryman) was the overseer at the Thacher summer property. Alvin Wagner replaced him after having earlier worked for Thacher doing projects at the cottage. He used materials purchased from Altamont’s Crannell Lumber Yard as was noted in The Enterprise.

Robert Thornton, who had recently established a stable at Altamont Driving Park and Fair Grounds, was in business training several well bred horses including a “handsome young horse belonging to Mayor Thacher of Albany.” This may have been “Nancy May,” Thacher’s horse that won a race run during an event of the Altamont Hose Company’s Field Day in 1896.

Thacher was also one of the group of summer cottage owners who formed a syndicate to buy the Helderberg Inn when there was concern it would fall into the wrong hands.

An 1897 article, “As Others See Us,” originally published in the Albany Sunday Press, reprinted in The Enterprise, included this line: “Not the least of Altamont’s charms is the delightful possibilities for social intercourse due to the presence of so many Albany families who occupy cottages there.

Among the list of summer residents, John Boyd Thacher’s name was included. However, if there were any local residents who may have had social contact with Thacher, there was never any word of it in print, unlike business contacts.

Preservation

One guest whose name did make the paper, although certainly not a local resident, was David B. Hill, former governor and former United States senator, a man very involved with Democratic politics. It was during Hill’s administration that land began to be set aside in the Adirondacks to preserve its wilderness. Perhaps Hill’s action had some influence on Thacher’s desire to preserve the area around Indian Ladder.

Thacher intended to continue his stay at his summer home as long as the weather remained warm, according to a note in an October 1906 Enterprise issue. He was always one of the last of the summer colony to return to the city, one of the “old Altamonters” as the writer referred to him.

October, when the autumn foliage was at its best, was according to Thacher, one of the most pleasant times of the year there. In his later years, Thacher settled into the routine of spending part of the year in Europe, adding to his collections while doing research; part of the year at his South Hawk Street home in Albany; and the summer and early autumn at his country home in Altamont.

Thacher began to take a real interest in the preservation of the historic and scenic area of Indian Ladder. At that time, much of the area around the top of the escarpment in the area of Indian Ladder had long been cleared and were hardscrabble farms that farmers were all too willing to sell.

A 1906 acquisition was detailed in The Enterprise when Thacher’s purchase included the C.F. Dearstyne farm along the top of Indian Ladder and a strip of land “some 60 acres in extent” of Simon Winne along the top of the mountain, this adjoining the Dearstyne property on the north. In addition he was in the process of negotiating for the purchase of a private road to the east end of Thompson’s Lake.

That same year, an Albany Argus article reprinted in The Enterprise, told that he had conferred with John M. Clarke, the New York State geologist, regarding his planned geological exploration of caves on the tract of land that Thacher had recently purchased. According to the article, this area was claimed to be “the richest and most interesting to geologists in this section of the country.”

This 1905 article already announced, “Mr. Thacher is anxious that this part of the mountain he owns shall be preserved from the ravages of man.” And, before his death, he and his wife, Emma Treadwell Thacher, had agreed that the land on the escarpment he had acquired be turned over to New York State. In the meantime, he allowed the public to visit the land he’d purchased.

Thacher died at his Albany home on Feb. 25, 1909. The Enterprise remarked, “Altamont loses another of her esteemed summer residents. He had been ill for more than a year past, being confined to the house most of the past summer while a resident here ….”

His widow continued to use the summer cottage for a few years. In 1914, she transferred to New York State the 350-acre parcel of the escarpment land, preserving a spectacular scenic and historic area combined with a huge number of fossils and deep caves.

It now became officially a state park and appropriately named John Boyd Thacher State Park. On the September 1914 day of the park’s dedication, Governor Martin Henry Glynn and the official party first arrived at the Thacher cottage where lunch was served before the group, accompanied by Emma Treadwell Thacher, went to the park for the dedication.

Finally, in July 2001, Emma Treadwell Thacher’s generosity in carrying out her husband’s wishes to donate this special area to the state for public use was recognized with the opening of a nature center named in her honor.

Eventually the Thacher cottage was sold to the Sewell family of Albany. After 1950, the cottage sat empty, abandoned, stripped of fixtures, and vandalized.

In the early 1960s, the property was purchased by the LaSalette Fathers whose seminary had been erected on the site of the old Kushaqua Hotel nearby. Wishing to erect a modern building on the site, the old cottage now described as “an eyesore” had to go.

The decision was made to remove it by burning it down as a firemen’s exercise. And so on Jan. 30, 1965, the “White House of Highpoint” came to a sad end. John Boyd Thacher’s last connection to Altamont was gone.

— Catalogue of the John Boyd Thacher collection of incunabula, a 1915 publication by the Library of Congress

John Boyd Thacher

For decades in the late 19th and early 20th centuries, late spring and early summer warm weather’s return brought several wealthy, prominent Albany families to the escarpment above Altamont to reopen their summer “cottages.”

Well known in their day, these affluent summer residents are long forgotten except for John Boyd Thacher whose name is attached to the nearby state park, although few know why or who he was or are aware of his association with Altamont.

A very wealthy man, Thacher’s affluence was derived from Thacher Car Works, founded in 1852 by his father in the north end of Albany. Manufacturing wheels for railroad cars including the New York Central System was a huge and very profitable business. As his father aged, Thacher and his brother became actively engaged in running the company.

Political involvement came next, a natural since Thacher’s father had served as Albany’s mayor during the Civil War years and after. A Democrat, John Boyd Thacher was first elected to the State Senate in l883 where he introduced legislation to construct a new capital building for one million dollars.

Next, he served as mayor of Albany in l886 when he organized a grand celebration on the occasion of the bicentennial of Albany’s city charter. After his term of office ended in l888, his involvement with politics continued as president of the New York State League of Democratic Clubs. He served a second term as Albany’s mayor in l896.

Attracting international attention, the Columbian Exposition, held in Chicago in l893, was a huge world’s fair attended by large crowds. Thacher became widely known when New York Governor David Bennett Hill appointed him to the commission to organize the New York State exhibit. He was also named national chairman of the awards committee for the exposition.

Interest in historical scholarship and research was another aspect of John Boyd Thacher’s personality. A discriminating collector of autographs, historical documents, manuscripts, and papers relating to the French Revolution, he was well known for his collection of l5th Century printed first editions called incunabula.

Much of his collection was donated after his death to the Library of Congress. In addition, he was the author of books on Shakespeare, Christopher Columbus, and a volume describing the evolution of maps depicting America during the early years of exploration. He made several trips abroad to do original research. At the time of his death in 1909, Thacher was in the midst of writing a book about the French Revolution.

Time in the Helderbergs

In the 1890s, John Boyd Thacher and his wife, Emma Treadwell Thacher, had begun to spend time in the Helderbergs above Altamont, their presence sometimes mentioned in The Enterprise. The date of his first visit isn’t known although an 1895 comment in The Enterprise noted that “John Boyd Thacher who has been spending the summer on the mountain near the village, has been nominated by the Democrats of Albany for mayor.”

An 1897 Enterprise article, “A Serious Runaway,” noted that John Boyd and Emma Treadwell Thacher had stayed “at the white cottage near the Kushaqua Hotel for the past several summers when describing a terrible accident involving a team belonging to Altamont liveryman Peter Hilton.

Just as Hilton was about to load some of Thacher’s luggage, the horses bolted, the runaways wrecking a buckboard owned by Judge Rufus W. Peckham, seriously injuring his two employees, and minutes later resulting in the death of one of Hilton’s horses. Thacher generously offered to pay for the buckboard, though no mention was made of the liveryman’s horse.

In November 1900, a news item reported that Thacher had purchased the late Paul Cushman’s summer home visible from the Kushaqua. Paul Cushman, an Albany merchant, had built the cottage in 1893, but sadly died there during the summer of 1895.

Thacher hired Albany contractors Feeney & Sheehan to do carpentry work on both the interior and exterior including the addition of a large extension. George Weaver, an Altamont mason, was employed to do the stonework.

In addition, Thacher intended to cut a private road beginning on Helderberg Avenue opposite Hellenbeck’s furniture store (now Fredendall Funeral Home) running up the gulch to his new home. Land had been purchased from George Severson for this purpose.

Altamont benefited economically from the demands for goods and services made by Thacher and other members of the summer colony above the village. Liverymen Peter Hilton and others were in demand to move people including the Thachers and their luggage for trips up and down from the depot before the automobile came into use.

Later Peter Hilton (though this may not be the same man as the liveryman) was the overseer at the Thacher summer property. Alvin Wagner replaced him after having earlier worked for Thacher doing projects at the cottage. He used materials purchased from Altamont’s Crannell Lumber Yard as was noted in The Enterprise.

Robert Thornton, who had recently established a stable at Altamont Driving Park and Fair Grounds, was in business training several well bred horses including a “handsome young horse belonging to Mayor Thacher of Albany.” This may have been “Nancy May,” Thacher’s horse that won a race run during an event of the Altamont Hose Company’s Field Day in 1896.

Thacher was also one of the group of summer cottage owners who formed a syndicate to buy the Helderberg Inn when there was concern it would fall into the wrong hands.

An 1897 article, “As Others See Us,” originally published in the Albany Sunday Press, reprinted in The Enterprise, included this line: “Not the least of Altamont’s charms is the delightful possibilities for social intercourse due to the presence of so many Albany families who occupy cottages there.

Among the list of summer residents, John Boyd Thacher’s name was included. However, if there were any local residents who may have had social contact with Thacher, there was never any word of it in print, unlike business contacts.

Preservation

One guest whose name did make the paper, although certainly not a local resident, was David B. Hill, former governor and former United States senator, a man very involved with Democratic politics. It was during Hill’s administration that land began to be set aside in the Adirondacks to preserve its wilderness. Perhaps Hill’s action had some influence on Thacher’s desire to preserve the area around Indian Ladder.

Thacher intended to continue his stay at his summer home as long as the weather remained warm, according to a note in an October 1906 Enterprise issue. He was always one of the last of the summer colony to return to the city, one of the “old Altamonters” as the writer referred to him.

October, when the autumn foliage was at its best, was according to Thacher, one of the most pleasant times of the year there. In his later years, Thacher settled into the routine of spending part of the year in Europe, adding to his collections while doing research; part of the year at his South Hawk Street home in Albany; and the summer and early autumn at his country home in Altamont.

Thacher began to take a real interest in the preservation of the historic and scenic area of Indian Ladder. At that time, much of the area around the top of the escarpment in the area of Indian Ladder had long been cleared and were hardscrabble farms that farmers were all too willing to sell.

A 1906 acquisition was detailed in The Enterprise when Thacher’s purchase included the C.F. Dearstyne farm along the top of Indian Ladder and a strip of land “some 60 acres in extent” of Simon Winne along the top of the mountain, this adjoining the Dearstyne property on the north. In addition he was in the process of negotiating for the purchase of a private road to the east end of Thompson’s Lake.

That same year, an Albany Argus article reprinted in The Enterprise, told that he had conferred with John M. Clarke, the New York State geologist, regarding his planned geological exploration of caves on the tract of land that Thacher had recently purchased. According to the article, this area was claimed to be “the richest and most interesting to geologists in this section of the country.”

This 1905 article already announced, “Mr. Thacher is anxious that this part of the mountain he owns shall be preserved from the ravages of man.” And, before his death, he and his wife, Emma Treadwell Thacher, had agreed that the land on the escarpment he had acquired be turned over to New York State. In the meantime, he allowed the public to visit the land he’d purchased.

Thacher died at his Albany home on Feb. 25, 1909. The Enterprise remarked, “Altamont loses another of her esteemed summer residents. He had been ill for more than a year past, being confined to the house most of the past summer while a resident here ….”

His widow continued to use the summer cottage for a few years. In 1914, she transferred to New York State the 350-acre parcel of the escarpment land, preserving a spectacular scenic and historic area combined with a huge number of fossils and deep caves.

It now became officially a state park and appropriately named John Boyd Thacher State Park. On the September 1914 day of the park’s dedication, Governor Martin Henry Glynn and the official party first arrived at the Thacher cottage where lunch was served before the group, accompanied by Emma Treadwell Thacher, went to the park for the dedication.

Finally, in July 2001, Emma Treadwell Thacher’s generosity in carrying out her husband’s wishes to donate this special area to the state for public use was recognized with the opening of a nature center named in her honor.

Eventually the Thacher cottage was sold to the Sewell family of Albany. After 1950, the cottage sat empty, abandoned, stripped of fixtures, and vandalized.

In the early 1960s, the property was purchased by the LaSalette Fathers whose seminary had been erected on the site of the old Kushaqua Hotel nearby. Wishing to erect a modern building on the site, the old cottage now described as “an eyesore” had to go.

The decision was made to remove it by burning it down as a firemen’s exercise. And so on Jan. 30, 1965, the “White House of Highpoint” came to a sad end. John Boyd Thacher’s last connection to Altamont was gone.

Location:

Over many decades huge numbers of Town residents have experienced Tawasentha Park’s rolling hills with its sweeping view of the Normanskill. Enjoying their recreational visit to the park, it’s the rare person who would stop to ponder that, like the other parts of the town, this spot and its environs must also have a history stretching back hundreds of years.

Imagine this scene 500 years ago. Silently, the Mohican hunters’ game-laden dugout canoe slipped through the clear waters of the wide creek bordered by vegetation and thick forest as they returned to their village on the river flats to the east.

With the arrival of the Dutch early in the 17th Century, the Mohicans began to be pushed off their traditional lands along the river that became known as the Hudson. No longer could they hunt and fish along this creek.

Archeological digs within our town along this waterway have proven indigenous peoples have camped, hunted, and fished at various spots along its banks in past centuries. Native Americans surely had their own name for this waterway teeming with fish and attractive to wildlife, emptying into the Hudson River to the east.

The Dutch establishment of the fur trade now brought Iroquois from the interior, their birch-bark canoes piled with furs navigating the creek as a route to Fort Orange. With the coming of the Dutch, the creek became known as the Normanskill after Albert Andriesen Bradt, a Norwegian who built a mill at the mouth near where it flowed into the Hudson River. Local Dutch settlers referred to him as “the Norman” leading to the waterway becoming the Normanskill.

Early in the 18th Century, the first Dutch settler known to have established a farm in Guilderland along the Normanskill was Evert Bancker, Albany merchant, mayor of Albany, and Indian Commissioner, who retired here to farm, living on this land until his death in 1734. Bancker was reputed to have often paddled a canoe up the Normanskill to visit his farm rather than traveling along Native American trails.

According to later town historian William Brinkman’s research, Bancker’s farm was situated across Route 146 from the entrance to Tawasentha Park. It is possible that some of what is now parkland was also part of his farm. Look for the state historic marker on the opposite side of Route 146 as you drive by.

Thoroughfare

In 1712, German Palatines, seeking a refuge in the Colony of New York, New Netherland having passed to the control of the English in 1664, were given permission to settle in the Schoharie Valley. Trekking through the wilderness and traversing a Native American trail after branching off from the dirt road through the Pine Bush known as the Kings Highway, they followed a route that later became known as the Schoharie Road.

They followed a route that crossed what is now Western Turnpike Golf Course, either cutting through what is now the park or passing nearby on their way to ford the Normanskill. The Palatines walked on foot on the narrow trail, but as years passed the route widened into a dirt road and for over a century was the approximate route used by most people traveling between Albany and Schoharie.

In 1849, the road was changed to connect more directly with the Great Western Turnpike when a group of investors laid out the Schoharie Plank Road to connect Schoharie with the Western Turnpike and Albany, improving the road with wooden planking. For this improvement, tolls were charged to travelers, there being a toll gate approximately opposite the entrance to the Tawasentha winter sports area parking lot.

And, for a few years after the Plank Road opened, there was a regularly scheduled stage coach passing by the farmland that eventually became Tawasentha Park. The construction of the Albany and Susquehanna Railroad through Altamont to Schoharie in 1863 put an end to the Plank Road and tolls, but the roadway continued to be used by local traffic, and eventually after some rerouting, was paved, now Route 146 familiar to us.

For generations, the hill to be climbed after crossing the Normanskill past the winter sports area was first known as Bancker Hill, later Buncker Hill.

Farmland becomes parkland

Fast forward to the 20th Century when this area of Guilderland was farmland and the Schoharie Road had become paved Route 146. Claude and Lucy Durfee produced fruit and vegetables on nearby farmland in the vicinity of Evert Bancker’s long ago farm, where they operated a roadside farm stand on Route 146.

Their son Alton Durfee grew up on this farm, spending many boyhood hours nearby swimming in “Buster’s Hole” along the Normanskill and roaming the surrounding area, now all part of Tawasentha Park.

Years later, Alton Durfee, who worked for General Electric, was living on Carman Road. Remembering his boyhood haunts, he had the vision of creating a recreational park there along the Normanskill. In the 1930s, others had had the same concept, hoping to create a campground, but after purchasing the property were unable to bring their plan to fruition.

By 1954, Durfee managed to acquire title to their 55 acres including his childhood swimming hole and several years later had the opportunity to purchase an adjacent 55 acre parcel.

A hard worker, Durfee, over the winter of 1955-56, built 50 heavy picnic tables at his father’s fruit and vegetable stand relocated on Carman Road where the family had moved. Alton Durfee Jr., a bulldozer operator, worked to clear land and build roads on their newly acquired Normanskill property. After much preparation, their park opened for business in 1957.

Alton Durfee Sr. originated the name Tawasentha Park. The word dates back to prehistoric times as the name of a Native American burial ground near the mouth of the Normanskiil where it flows into the Hudson.

Its translation is supposed to mean “Hill of the Dead,” a location that had special meaning for both the Mohican and the Iroquois tribes.

Nineteenth-Century poet Henry Wadsworth Longfellow, influenced by Guilderland native Henry Rowe Schoolcraft’s studies of Native Americans, used the term “vale of Tawasentha” in his well-known poem “Song of Hiawatha.” Longfellow described the vale as a “green and pleasant valley, by the pleasant water-courses” in his epic.

Surveying Enterprise notices, one can see Mr. Durfee’s new park opened at just the right time to fulfill the need for a local recreation area, attracting over the next few years not only Guilderland residents, but those of nearby towns.

It was an extremely popular spot for family reunions, church groups, fire departments and their auxiliaries, school classes, fraternal groups, Sunday school classes, Scouts, businesses — you name it and some sort of organization announced a picnic, steak roast, or clam bake at Tawasentha Park over the next few years.

Under Durfee’s ownership, many improvements and attractions were added to the park’s appeal. The Durfees advertised their park in The Enterprise in the early 1960s as the “Fun Spot of the Capital District” with acres of picnic groves “in the rolling hills and ravines of the beautiful and scenic Vale of Tawasentha.” Certainly advertising would have appeared in other local publications as well seeking to attract visitors from the whole Capital District.

The Durfees offered to book and cater organizations’ outings and claimed it was a perfect location for school picnics. Within a few years of opening, there was a pavilion, rides, games, and a snack bar. The park was open seven days a week, and Durfee family members worked a punishing schedule during the months the park was open.

The added attraction with the most appeal was Paddock Pools’ installation in 1964 of a $40,000 swimming pool, which was 95-by-108 feet in size. In addition to daily visitors swimming, membership for seasonal pool use was also offered for one price including the use of a members-only picnic grove.

With the pool open to the public daily, lifeguards were required. In 1965, an American Red Cross lifesaving course was offered for high school juniors and seniors who were strong swimmers and were interested in doing lifesaving work during the summer. At the conclusion of the 1967 course, 37 students had completed the course. Eventually, the town began to sponsor a Red Cross Learn to Swim Program for elementary school children.

One improvement the Durfees sought to add to their park was the establishment of a regulation Go-Kart track for Go-Kart Association racing approved by the United States Go-Kart Association Inc. A public hearing was held in September 1961.

There was neighborhood opposition and the application was rejected. Alton Durfee applied again in January 1952 when it was again rejected by the town’s zoning board. However, park ads noted Go-Kart riding was allowed in the park, but there were no races.

The Durfees’ park was a huge success, but administering it meant they were putting in 90 to 100 hours a week operating the busy park during the months when it was open. By 1967, Alton Durfee began to think seriously about selling it.

Town park

Fortunately, Guilderland voters had elected forward-looking town Supervisor Carl Walters, who obtained a two-year option on the property. At that time, the price quoted was $295,000 and the town board gave its approval assuming that aid would be coming from both the state and federal governments.

The two-year time period was used to apply for governmental aid to pay three-quarters of the cost, leaving the town with about $73,000 to cover. This would result in a tax rate increase of 21 cents per $1,000.

Mention a tax-rate increase, no matter what the cause, and there will be people opposed. Not all Guilderland residents were thrilled about taking on the cost of owning a town park and swimming pool.

A group calling itself the Guilderland Civic Association claimed that it had collected 1,000 signatures on a petition calling for a public vote on the proposal. The town board rejected the petition.

Letters to the Enterprise editor reflected the opposition, some with arguments for a town referendum. One asked why the town wanted to take over the cost of a park when it was already available to the public at no cost to the taxpayers while another couldn’t understand why the town didn’t buy cheaper land in another part of Guilderland if it wanted a park.

The final closing was April 4, 1969. Tawasentha had become Guilderland’s town park, thanks to the foresight of Supervisor Walters and the town board members.

Since that time, additional land has been added to the park and there are many more attractions available to the public, including hiking trails, tennis courts, the band shell, community gardens, a climbing barn, the winter sports area, and a headquarters for the town’s Parks and Recreation Department.

Indeed, it is Guilderland’s gem, the latest chapter in the long history of that spot in our town.

Rising in wetlands near Duanesburg, the Normanskill flows 45.4 miles downstream through the towns of Guilderland, New Scotland, and Bethlehem to its confluence with the Hudson River.

Native Americans called the stream Tawasentha or “place of the dead,” a name inspired by a sacred native burial ground near its mouth. Here they found abundant food supplies in its pristine waters and along its wooded banks, their presence proven by the numerous archeological remains found nearby.

Change came with the arrival of the Dutch in the early years of the 17th century. When, in the 1630s, Albert Andriessen Bradt established a mill at the creek’s mouth, the stream became known to European settlers as Norman’s Kill due to the Norwegian ancestry of Bradt, called the “Norman.” With the advent of the fur trade, the waterway became a major Native American trading route to Fort Orange where Albany is today.

Sometime before his death in 1734, Evert Bancker, the former Albany mayor and merchant, came up the Normanskill to establish what was likely the first farm in Guilderland. It was located along the creek approximately across from the entrance to modern-day Tawasentha Park. (A state historic marker denotes the place.)

He was followed by settlers such as Jacob Vrooman and Abraham Wemple who also established farms on the fertile lands along the waterway in the years before the American Revolution. Eighteenth-Century settlers were described as “of the Normanskill” in the absence of a more specific address.

After the Revolution, the fertile soil produced huge quantities of broom corn. Later farmers switched to hay, oats, and rye.

Frenchs Hollow

The waters of the melting Ice Age glacier had cut through bedrock to create a ravine that by 1800 had become known as Frenchs Hollow. Named after Abel French who, having taken advantage of the water power, had begun operating grist and saw mills in this location by the end of the 18th Century.

The grist mill remained in operation here until the early 20th Century. French’s early textile mill failed, replaced by Peter K. Broeck’s larger textile mill, erected nearby.

After the factory failed, the empty building became used for social gatherings until the turn of the 20th Century. The hollow itself was a place of natural beauty where generations of Guilderland residents fished, swam, and picnicked.

Watervliet seeks clean water

During the first decade of the 20th Century, typhoid had become an increasingly serious health issue in the city of Watervliet as the result of contamination of the city’s water supply. Watervliet’s water source was then the Mohawk River near Dunsbach Ferry, water which had become more impure as the upstream cities and industry expanded.

Searching for a replacement source of safe, pure water, in 1912 or 1913 the city fixed on the Normanskill in Guilderland where it would be practical to dam the Frenchs Hollow ravine. In addition, the area to be flooded behind the dam was relatively inexpensive farmland that could be acquired by eminent domain if necessary.

The Watervliet City Council agreed to purchase the land projected to be about 700 acres necessary for “not less than $477,000 or more than $562,000.”

November 1913 brought news in The Enterprise that surveyors were working at Frenchs Hollow because of Watervliet’s plans to locate a dam there. Yet the next summer, the project did not seem final when the Enterprise stated, “The City of Watervliet is again agitating the question of securing a new water supply from French’s Mills.”

A 1914 map entitled “Map of Watervliet, NY & Vicinity showing proposed Municipal Water Supply from the Normanskill at Frenchs Mills” was published. Watervliet taxpayers seemed to be objecting because of the high cost of securing water privileges and acquiring land, while the Watervliet Hydraulic Company, apparently a private entity supplying Watervliet’s water from the Mohawk, was also opposed.

A major expense had been added to the project when the New York State Conservation Department insisted on a requirement for the project that a filtration plant had to be constructed in addition to the dam and the infrastructure needed to pipe the water from the reservoir to the city of Watervliet. The cost of the whole project was estimated by the Enterprise’s editor to possibly run as high as $500,000.

The next year, 1915, brought another surveying crew who put up at Borst’s Hotel in Guilderland Center. Once Watervliet had acquired the old French property at the hollow, officials next purchased the nearby farms of Richard Van Heusen and Herman Vincent just outside of Guilderland Center.

A few months later, the notices of auctions scheduled to take place at their soon-to-be vacated farms for the dispersal of their farm equipment were advertised.

Construction underway

By then, the contract to construct a concrete dam 35 feet high at the hollow had been awarded to a New York City firm and work had begun by 1916. A notice of a man’s death on the West Shore tracks identified him as a “laborer on the construction work of the new reservoir for the City of Watervliet at Frenchs Hollow.”

Considering that, except for steam shovels and possibly dynamite, other work had to be done with hand tools, this was a major construction project that would take many months. The derelict factory building was demolished and a pumping station built on its site. The dam seemed to have been completed by 1917 at the latest.

Acquisition of more than 600 acres of land along the Normanskill and the Bozenkill, a major tributary, was necessary. Land purchases were still being negotiated in 1916 when the Enterprise editor commented that the price of farmland “has taken a big jump lately on account of the building of the new Watervliet Reservoir and dam.”

His update noted that some farms had been acquired or were about to be acquired. In the area which would become the upper end of the reservoir, a farmer named John Moore planned to relocate to a farm at Parkers Corners and at least three members of the Sharp family lost all or part of their ancestral farms.

Holdouts

However, members of the Woodrich family, the last owners of the historic Wemple farm in Fullers, were not about to be forced to give up their approximately 56 acres plus without a fight.

Designated the “Wodrich Estate” in the Enterprise’s two mentions of this dispute, Guilderland historian Arthur Gregg later identified the last owner of the historic property as Richard Woodrich.

The family seemed to be from out of town, seeing as they had not only hired two Albany lawyers, but additionally a New York City law firm to fight the proposed acquisition or possibly the price the Watervliet officials offered to pay for their land. Another lawyer represented the property’s tenant.

To settle the dispute, the Albany County Court appointed a three-man committee including William Brinkman of Dunnsville to view the property and take testimony. The matter went to the New York State Supreme Court where the Watervliet Water Board requested the condemnation of the Woodrich property.

With the city having the power of eminent domain, the Woodrich family didn’t stand a chance. The final outcome of the case received no mention in the Enterprise. In the 1930s, Gregg mentioned that the Woodrich Estate received $16,000 for 60 acres with the family retaining that part of the property along Route 20.

Writing in “Old Hellebergh,” Chapter 18, Gregg offered a poignant description of the demolition of that treasure of Guilderland’s heritage, the 18th-Century Wemple homestead:

“…The house was built by the Vroomans in 1780 out of very large, extra sized brick made right there out of the clay from the bank near the barn. Some of you witnessed the destruction of this solid old house at the construction of the reservoir twenty-five years ago, and marveled at its workmanship. The farm was known at various periods as the Wemple, the Sigsbee, the Myers Farm, and, at the time of the flooding, belonged to Frederick Woodrich.”

The town of Guilderland recently refurbished an historical marker to denote the site.

Election Day 1918 found Frederick J. Van Wormer seeking re-election as Guilderland town supervisor. A Republican Party advertisement characterized him as a “scrapper” for having taken on the city of Watervliet, managing to get the city to restore the damage done to town highways in the process of construction of the dam.

Also, never mentioned, but pipes had to be laid across town land and Route 20 to bring the water to Watervliet. In addition, the state of New York was forced to build a new higher iron bridge at the upper end of the reservoir due to the rising water levels at the point of the Normanskill’s flow into the reservoir where the Osborn Corners-Schenectady Road crossed it.

Now Route 158, the road had already become a state route at the time of the dam’s construction.

What right did Watervliet have to come into Guilderland, build a reservoir here ,and force local farmers to give up their farms? Obviously an agreement was made with the Guilderland Town Board in 1912 or 1913, but the details are unavailable.

Riparian rights?

In the years after 1960, when Guilderland’s rapid growth sent town officials on a quest for additional water supplies, the Watervliet Reservoir was again in the news. A statement by Guilderland Town Supervisor Carl J. Walters in 1977 announced that the town was limited by law as to how much water it could purchase from Watervliet.

He claimed, “This limitation of 2,000,000 gallons per day was set many years ago when Watervliet purchased the reservoir from the town. Hindsight tells us that the sale of the water supply was not a prudent move by the local officials at the time.”

The late Fred Abele, a very reliable local historian, focused on a different aspect when he claimed in a 1984 “McKownville: News and Comment” column that Watervliet had retained riparian rights dating from the time of the formation of the town of Guilderland in 1803.

(In 1788, the state of New York divided the entire state into towns; the town of Watervliet included most of what is now Albany county as well as most of what is now Niskayuna in Schenectady county.)

Apparently, when the town of Guilderland was created from the town of Watervliet, the water rights did not automatically pass to the new town. Noting he had been a member of the townwide Water Advisory Board for a number of years, perhaps Mr. Abele had access to information not generally known.

This legal point may be the reason why the Guilderland Town Board members of 1912 or 1913 acquiesced when the city of Watervliet announced its intention to create a reservoir in the midst of our town.

Today, a portion of Guilderland’s water supply comes from the reservoir. In addition, a hydroelectric plant generates power on the site. Perhaps, in the long run, it has worked out for the best for both Watervliet and Guilderland that the reservoir was created on the Normanskill.

— Photo from the Guilderland Historical Society

This is a view of the grist mill demolished in the 1920s and the covered bridge just beyond it. Both were gone by the early 1930s. You are looking downstream. The old factory building would have been down a bit beyond the bridge. This photo was most likely taken not long before the old mill in disrepair was razed.

A century or more ago, Frenchs Hollow would have been a familiar landmark to just about everyone in Guilderland, most of them having actually visited the scenic spot on one or more occasions. Today it is probable that the majority of Guilderland’s 37,000-plus residents have never even heard of the place, much less visited it.

Melting waters from the last Ice Age’s glacier carved through bedrock to create a narrow ravine. An ever-flowing creek later named the Normanskill followed the contour of the land to establish a streambed between the narrow banks. Evidence of Native American activities in this area have been uncovered by archeologists.

Here the rushing waters had the potential for water power, a key resource needed for early 18th-Century settlement, making the area attractive for a small number of Guilderland’s early settlers. The 18th- and early 19th-century history of the hollow is fragmentary.

Certainly by 1800 the spot had become known as Frenchs Hollow or Frenchs Mills due to the entrepreneurship of Abel French who had used the Normanskill’s water power to establish a saw mill, grist mill, and a cloth factory. Peter K. Broeck set up a woolen factory in 1795 as well.

Workers settled there, but Frenchs Hollow never was considered one of the town’s hamlets, lacking a one-room school, post office, church, or even a store. Guilderland Center or Fullers served the needs of Frenchs Hollow’s residents.

Revolutionary times

A tavern run by Jacob Aker, otherwise unknown, was supposed to have been in the hollow at an early period. Was it a meeting place for Revolutionary War Patriots?

According to French’s 1860 Gazetteer of New York State, to celebrate the good news of Burgoyne’s defeat at the Battle of Saratoga in 1777, at the top of the hill across the Normanskill a hollow chestnut tree was filled with a barrel of tar and set ablaze.

Another story associated with Burgoyne and Frenchs Hollow was recorded in an 1880s composition by a schoolgirl descendant of the Chesebro family who lived on the old Wemple farm not far west of the hollow.

It seems equipment carried by the defeated British forces was confiscated and brought south to Albany. Somehow one of these items, an oversized copper kettle with a “huge faucet as big as a man’s wrist” at the bottom, was obtained by Abel French.

French thought he’d find a use for it in his cloth factory, but eventually tossed it out into the lumber yard of his saw mill. A quarter of a century earlier, the girl’s grandfather as a schoolboy had measured the abandoned kettle, reporting it to be five feet deep and six feet across.

Changing uses

Early in the 19th Century, Abel French’s original cloth factory burned and the large brick building seen in late 19th-Century photographs was erected in its place. Supposedly the building wasn’t sturdy enough to accommodate later, heavier machinery so that it could no longer be used for manufacturing or weaving.

It is also likely that by the mid-19th Century, competition from other areas had an effect as well. The grist mill continued to operate into the early 20th Century because buckwheat and rye were important farm crops grown on Guilderland farms at that time. Locals called the buckwheat flour ground here “pancake timber.” The building was taken down in the early 1920s.

After Abel French’s death, the family continued to own the mill and factory building, leasing it out to others. Elijah Spawn and Son ran the grist mill and rented out the factory for social occasions, the scene of many a large gathering during the last decades of the 19th Century. However, it was still owned by the French Estate, a term used in The Enterprise.

Frenchs Hollow was located off of the Western Turnpike and the Schoharie Road, later called Schoharie Plank Road. Dirt roads connected to these main routes gave access to the mills there and today are designated Frenchs Hollow Road and Frenchs Mills Road.

It is no longer possible to access Frenchs Hollow from Route 146 by car as it once was because the Frenchs Mills Road railroad overpass is closed while the bridge over the Normanskill at the Hollow is now restricted to cyclists and pedestrians.

The Normanskill had to be bridged, but information about the earliest bridge is unknown. However, in 1869, a “spring freshet” washed out whatever bridge was there.

A Haupt style covered bridge, with a span of 62 feet, 8 inches, was built on the original stone abutments; this covered bridge is seen in many old photos. According to his descendants, Henry Witherwax was supposed to have constructed the trusses on open land near Fullers Tavern on the Western Turnpike, and then skidded them down to the Normanskill.

Twentieth-Century traffic took its toll and, in 1924, a motorbus’s rear wheels broke through the planking; it took five hours to get it unstuck. In 1933, the now inadequate covered bridge was demolished, replaced by a bridge that has been in turn judged inadequate and closed to motor traffic in 1987.

“Modern” technology encroached on Frenchs Hollow in 1865 when the Saratoga & Hudson Railroad was laid out, linking the New York Central tracks in South Schenectady with Athens, a village on the Hudson. Crossing the ravine at Frenchs Hollow was a major engineering and construction project for the time when a wooden trestle was built on stone abutments to support the tracks.

This first railroad was unprofitable, but the route was taken over by the New York, West Shore and Buffalo Railroad in 1883. Rebuilt more than once since that time to carry heavier and longer trains, the railroad trestle at Frenchs Hollow carries numerous, lengthy CSX freights daily and has never been out of use since the 1880s.

Social gatherings

During the 19th Century, Frenchs Hollow became a popular destination for social events, both indoors in the otherwise unused factory building and outdoors. It was a tradition for many years that the Sunday schools from the town’s churches join together there for a Town Picnic.

A popular spot at Frenchs Hollow, mentioned often in The Enterprise once it began publication in 1884, was Volkert Jacobsen’s two islands where there was a fine spring, spacious grounds, and plenty of shade. The exact location is unknown today, but the islands are probably now under the waters of the reservoir.

Elijah Spawn, who owned a farm there, also had a grove available for picnics. Food, ice cream, and baseball games were key features of the Sunday school picnics and, in 1889, it was estimated that 2,000 kids, parents, and friends attended with the Knowersville Band, and the Guilderland Center and Guilderland Drum Corps furnishing music “to the delight of all.”

In the 1890s, A.F. Spawn apparently remade his farm located on “the rapids” and likely under the waters of the reservoir today, into “Hillside Cottage,” a mini resort with a large tent adjacent and “Entertainment Hall,” probably the old factory building.

Guests, some traveling from nearby cities, others from nearby local hamlets, came to hear Sunday afternoon preaching or other entertainments in the tent or to attend dances in the “Hall.” All these activities were recorded in the Guilderland Center’s Enterprise column, although by the late 1890s mentions were no longer made of Hillside Cottage.

The old factory building, having been leased by Elijah Spawn and Son in the 1880s, had been repurposed into a venue for group gatherings. As early as the 1840s, before any of the town’s Methodist churches were built, Methodists had camp meetings at Frenchs Hollow, although they may have had open-air meetings rather than using the factory building.

A hugely popular event took place there the summer of 1887, just one example of the entertainments at Frenchs Hollow. It was given by the I.O. of G.T. (the International Organisation of Good Templars) of Guilderland Center where at 3:30 p.m. there was a baseball game, then a peach supper at reasonable cost, and an evening’s dramatic and musical program including two elocutionists from Amsterdam, and the Fullers Cornet Band and the Guilderland Center Boys Drum Corps to provide the music.

Let’s not forget that most arrived by horse and buggy and attendees were assured “two competent hands have been engaged to take care of the horses.”

A once well-known local poet, Magdalene LaGrange used one of these dinners followed by entertainment as the subject of a lengthy 120-line narrative poem composed in the 1880s entitled “The Drill.”

Beginning with, “An old factory three stories high, a basement below…,” it recorded the scene of one of these dinners with “The sandwiches, biscuits, pie and ham/ The cake, the preserves, the jelly and jam…” and told of the entertainment, describing a broom drill performed by “Twelve young ladies dressed in white/ Composed the drill we saw that night … The tall sweet leader’s name was Nell…” to the tune of “Bonnie Doon” played by a cornet band.

Both Guilderland Center’s Helderberg Reformed Church and St. Mark’s Lutheran Church made use of the building which Spawn advertised as “a large and commodious space” on two floors with “ample accommodation for horses.” The two churches alternated putting on suppers and entertainments there on Decoration Day (Memorial Day) for many years.

Finally, in 1901 the Reformed Church Ladies Social Union announced that the annual supper and entertainment would be at the church parlors in Guilderland Center, noting “for several years the old factory in Frenchs Hollow has generally felt to be unsafe and is generally felt that no considerable body of people should gather in the building.”

Factory demolished

The old factory building remained empty and decrepit until 1917 when it was taken down as part of the construction of the Watervliet Reservoir.

In 1917, the Watervliet Reservoir construction dammed the Normanskill after the city of Watervliet purchased much farmland in the area of Frenchs Hollow. As part of the reservoir project, the old factory building was removed and in its place a pumping station was built.

In the 20th Century, the hollow continued to be an outdoor recreation area for both children and adults. After the turn of the century, Sunday school picnics were more likely to be organized by individual churches, mainly Guilderland Center’s and Altamont’s.

Try to imagine the excitement of the 10 Altamont lads from Mrs. David Blessing’s Sunday school class who were crammed into Mr. Montford Sands’s touring car one summer day in 1908 to motor to Frenchs Hollow for a picnic.

Other picnickers over the years included Boy Scouts, Camp Fire Girls, and junior 4-H girls who were practicing campfire cooking. Hot-dog roasts were almost always mentioned as being on the menus. It was also a popular spot for adults to picnic informally and for decades the Normanskill provided a swimming hole attractive to all ages.

Over the centuries, Frenchs Hollow has evolved from what must have been an excellent hunting ground and fishing waters for Native Americans to a prosperous early American settlement based on water power.

During the 19th and 20th centuries, the scenery attracted local folks as both an outdoor and indoor recreation spot. Once the mill, covered bridge, and old factory buildings were gone in the 20th Century, it was no longer so charming, but the popular swimming hole remained and that’s what many of today’s Guilderland’s residents associate with Frenchs Hollow.

Editor’s note: When writing about local social history, it’s important to examine the ugly parts as well as the heroic parts. In this column, Mary Ellen Johnson takes an unflinching look at a racist form of entertainment that Enterprise reports show was both unquestioned and popular as late as the 1950s.

During the 19th Century, minstrel shows were professional performances presented in theaters where paying audiences were entertained by white actors in blackface who sang, danced, and performed variety acts and comedy. Sometimes Black performers also participated.

The premise was to satirize and ridicule Black culture by imitating and exaggerating their dancing, manner of speech, supposed ignorance, and music. Today this type of performance would be considered outrageous and racist.

It simply wouldn’t be done, but until the 1960s and beyond the majority of Americans had little problem enjoying entertainment featuring this racist representation of Black Americans.

Since 1884 when it first began publication, The Altamont Enterprise has been the chief source of information about the social history of Guilderland and the surrounding towns. There are 771 references to minstrel shows in the paper’s digital index, proving minstrel shows were a highly popular and newsworthy form of entertainment, not only in Guilderland, but in all the local areas covered by the newspaper.

The last professional minstrel show to appear on Broadway in New York was in 1909. Before this time, references to minstrel shows in The Enterprise were rare. One of the paper’s earliest editions ran a short piece reprinted from some other publication titled “Actors in Burnt Cork” in which “two noted minstrels speak on different styles of fun” in what would now be unprintable racist terms.

Occasionally during these early years there was the opportunity to view touring Black performers locally. The Fullers Station correspondent reported in1889 that “a colored minstrel troupe with a donkey” had traveled through, stopping at the local one-room school to perform, noting that the people who attended agreed it was “well worth the price of admission.”

At the 1902 Altamont Fair, a “genuine colored troupe” was hired to perform “the latest Negro specialties.” A decade later, a “big colored company” put on “Way Down South in Dixie” at Altamont’s Masonic Hall, a show featuring “genuine southern scenes, dances and melodies.”

An early local exposure to a minstrel show occurred in 1894 when a group of Albany amateurs traveled to Altamont, performing at Union Hall on Maple Avenue. The evening’s proceeds were to benefit the Fresh Air Fund, beginning the tradition in this area at least, that raising money for an organization became the reason for future minstrel shows to be scheduled in the area.

When the Hamilton Union Church reported on the success in1922 of the minstrel show it put on at the old “town hall” in Guilderland Center, $83 had been taken in at the door. Obviously it had been a popular attraction.

Before 1920, there were few mentions of minstrel show performances, although the Altamont Athletic Association advertised one in 1914. As time went on, minstrel shows were noted in The Enterprise more frequently. Altamont’s Colony Club used “home talent” in 1920 for its show while a year later Guilderland Center Fire Department members were planning to perform at the old “town hall.”

Radio influence

Was the increasingly frequent mention of local groups in the 1920s putting on minstrel shows tied in with the popularity of movies and that new medium radio? Al Jolson appeared in blackface in several movies, the most famous being “The Jazz Singer,” a smash hit.

During the era’s silent movies, there was much stereotyping of Black culture in the same vein. Locally, WGY’s radio programs were listed weekly in The Enterprise. For the week of May 18, 1922 listed among the station’s offerings were:

— Introducing Some Darktown Humor;

— Georgia Minstrel Boys;

— Male Quartette: I Wish I Was in Dixie; and

— Humorous Dialogue: William Jackson & Washington Lee.

After going on the air in 1928 “Amos ’n’ Andy” quickly became the nation’s favorite radio comedy with two white actors playing two African-American men who had moved from the country to Chicago to start the Fresh Air Taxi Co. It lasted until the early days of TV in 1953.

Many white Americans saw nothing wrong in these comic characterizations of the Black community because racism was so prevalent in American life during these decades.

During the next three decades, groups from all over Guilderland and other area towns volunteered their time and talent to produce minstrel shows to amuse their neighbors and at the same time raise funds for their organizations. Several local churches, fire departments, clubs, and civic groups got into the act, sometimes giving repeat performances in different locations.

The minstrel show as a community activity and entertainment flourished until the civil rights movement and changing attitudes made this kind of performance untenable.

Three-part form

The Enterprise articles announcing upcoming minstrel shows almost always placed the advance publicity on the front page. In the publicity notices, terms were mentioned such as endmen and olios, unfamiliar to later generations.

The Altamont Entertainers Guild presented a minstrel show and olio in 1948. The audience applauded and laughed loudly at the endmen’s jokes and antics. A 1946 production put on by the Altamont Fire Company featured endmen named “Charcoal, Debris, Embers and Smokey.” Others in the cast included “Amos, Andy, Bones, Evelina, Heliotrope, Mandy, Rastus, Sambo and Violet,” all singing old-time musical numbers.

There was a three-part form to traditional minstrel shows. First, the full ensemble sat in a semicircle with Mr. Interlocutor in the center and blackface comedians at either end. These were the endmen who spoke in colloquial Black speech while Mr. Interlocutor used an exaggerated, elegant pattern of diction, both getting the comedy rolling.

After an intermission, the olio followed with a variety of songs and acts and a speech by one of the endmen poking fun at the issues and political figures that could be personalized to fit the community.

After a second intermission, there was another piece with the two endmen playing two Black buffoons, a country bumpkin type and a city slicker know-it-all who is easily tricked.

Local groups of differing sizes and talents may have followed their own pattern, but the basic element of characterizing Black culture remained the same. Many traditional minstrel songs reflected the image.

Some went all the way back to Stephen Foster’s melodies, while other were like the 1890s hit about a Black woman unable to choose between two suitors entitled “All C**** Look Alike To Me.”

A 1930 production put on by the Altamont Lady Minstrels not only had a cake walk contest, but songs by a sextet made up of “Turpentina, Vasolina, Listerina, Benzina, Gasolina and Energina.”

Friends on stage

The great attraction to the public was seeing their friends and neighbors in the cast and figuring out “who is who” was noted when the Goodfellowship Minstrels announced their show to be performed at Altamont’s Masonic Hall, promising it to “Be the Hit of the Season” in 1924.

Often it wasn’t that the comedy itself was all that hilarious, but the incongruous situation of a church elder, proper matron, or local businessman doing the nonsense involved.

The Guilderland Center Fire Department’s 1953 minstrel show with a cast of 40 assured the prospective audience “When you see Clyde S……. doing a ballet with Ormond B…. you will have tears rolling down your cheeks,” both men being well known in the community at that time.

This particular show was performed two nights in Guilderland Center, after which it was announced, “the Center Dixie Minstrels to Hit the Road,” giving two additional performances of two nights each in other locations.

Were these shows popular? A 1934 headline promoting an upcoming minstrel show said it all: “Advance Sale of Tickets Indicates a Capacity House.”

By the end of the decade of the 1950s, the Civil Rights Movement and growing sensitivity about the treatment of America’s Black population led to the end of the local minstrel show.

Today, reading this description of the traditional minstrel shows performed in our own town makes us cringe, but it surely illustrates how this facet of racism was part of the fabric of life during the first half of the 20th Century. No longer acceptable, minstrel shows have been relegated to our past social and racial history.

— From the Guilderland Historical Society

This pre-1927 photo of the original entrance to Guilderland Center as it was before the overpass was erected shows poles carrying electric lines down the main street. Residents living along the side roads waited for years for lines to reach their neighborhoods.

“De-lighted” was the general consensus when, at 4:37 p.m. on Jan. 20, 1916, electric current flowed through wires strung into Altamont by way of Voorheesville and Guilderland Center. Local folks were well aware of the convenience and superiority of electric power, eager to simply flip on a light switch.

After all, articles about the wonders of electricity had appeared in The Enterprise and other publications for decades and most townspeople at one time or another had hopped the train for Albany or for a holiday excursion on one of the local railroads to experience it for themselves.

However, much as with internet cable today, utilities such as the Municipal Gas Company of Albany would run electric lines only to sites where they could profitably reach a cluster of many potential customers in a small area. Altamont, and to a lesser degree Voorheesville and Guilderland Center, fit the bill and the company decided to connect with the line already reaching as far out of Albany as Slingerlands.

Initially, the Municipal Gas Company’s proposal to bring electric power to Altamont met with resistance due to the village’s own gas works. However, when the Albany Company arranged the sale and removal of the gas plant and streetlamps to a Coeymans’ man for $2,200 (approximately $56,100 in 2022 dollars) the franchise to bring in electric lines and put up streetlights was then awarded to the gas company by the Altamont Village Board.

With the agreement finalized, poles began to be set along the main road between Slingerlands and Altamont, about 15 per day on most days, covering about one-half mile daily. In anticipation of the power being turned on within coming weeks, many Altamont buildings including the Altamont Hotel, the Altamont Pharmacy, National Bank, The Enterprise, and several private homes were being wired for electricity.

Once the power would be turned on, gas production would cease, giving Altamont residents the choice of either wiring for electricity or reverting to kerosene lights.

Many homeowners opted to wire their homes as quickly as they could contract to get the job done, their names appearing week by week in the local columns for Altamont and Guilderland Center. The Reformed Churches in both Altamont and Guilderland Center and Altamont’s Lutheran Church immediately wired for electricity.

The cost of Guilderland Center’s Helderberg Reformed Church and parsonage was $500 (approximately $12,750 in today’s currency) and within a year was paid for.

Jesse Cowan and A.J. Manchester were the two Altamont electrical contractors who seemed to be doing almost all the wiring in Altamont and Guilderland Center and a few years later in the hamlet of Guilderland when power finally reached that section of town.

When Altamont’s 75 new streetlights came on, it was noted that the results surpassed residents’ fondest expectations. Previously, Altamont’s village streets had been dimly lit by 35 acetylene gas lamps provided by the Altamont Illuminating Company. Lit at dusk, they were extinguished at 10 p.m. except on moonlit nights when they remained dark.

In Guilderland Center, home and business owners who could afford wiring also immediately began investigating getting electric water pumps installed, allowing them to have running water, indoor plumbing, and flush toilets — no more hand pumping water or trips to the outhouse.

Altamont already had had a municipal water supply for years. The mention in the Guilderland Center column a few years later that one woman was “pleasantly surprised” with a birthday gift of an electric washer shows how delighted people were with these new labor saving devices.

A notice in The Enterprise alerted folks with newly wired buildings that their insurance would be void if they did not attach a “standard electricity permit” to their policy.

Innovations abound

Lighting was not only a boon to electrical contractors. At least two local young men became electrical engineers and left town to work for large companies.

The Enterprise had a bonanza selling ad space to contractors; the Municipal Gas Company of Albany, which ran large ads tempting consumers with all kinds of electrical appliances; and to Albany department stores — W.M. Whitney’s had a special sale on a set of lighting fixtures, enough for a six- to seven-room house, a $45 value for $29.95 (which would be $763 today).

Even the Altamont Pharmacy had begun to sell small appliances and electrical supplies including Christmas lights.

Schenectady’s General Electric plant was booming, providing employment for many local young men whose names were mentioned in the columns covering the different areas of town. Several times in 1917, G.E. actually placed help-wanted ads in The Enterprise, seeking office boys, young women between the ages of 18 and 30 needed to operate sensitive drill presses and do small assembly work, and young men with high school training.

Exciting innovations began to pop up. At a Christmas party at the “old town hall” in Guilderland Center, the “little tots” were mesmerized by the Christmas tree “bespangled with decorations and electric lights.”

In Altamont, a lighted sign advertising Forest City paints appeared in Lape’s Paint Store window. And at the Masonic Hall the 10-cent ($2.55 today) silent movies were now shown using the “new electrical apparatus,” which was “equal to any city theatre.”

Gaglioti’s barbershop boasted a lighted barber pole in front with not only interior lights but an electric massage machine. The pharmacy may have had a new electrical machine for shaking malted milk drinks, but topping that was the new corn-popping and peanut-roasting machine that was run, heated, and lit by electricity at Keenholts’ newsroom, a really big attraction for the curious.

Almost no one would argue that electricity was not an improvement over the past, especially when each year at the Altamont Fair all sorts of appliances and labor-saving devices were on display and demonstrated.

But installation, including wiring, fixtures, revision of insurance policies, and monthly utility bills, required a degree of affluence. Not every church could afford to do it immediately — Guilderland Center’s Lutheran Church took until 1920 and St. Lucy’s Church in Altamont was wired in 1922 when other renovations were being done.

Altamont’s high school building was finally wired in 1921 after taxpayers had voted it down once in spite of power having been available since 1916.

High demand, slow progress

What about other areas of Guilderland? One of Albany’s electric trolley lines ran out to the border of McKownville by the turn of the 20th Century, but no information could be uncovered telling just when power lines began to be extended along the Western Turnpike.

Since a 1918 letter to The Enterprise from “a citizen” mentioned electric lines had been installed to a point on the turnpike one mile east of the hamlet of Guilderland and stopped there, obviously by then McKownville had electricity.

It was only in 1920 that the mention of Guilderland individuals and the foundry installing electric wiring appeared in Guilderland’s Enterprise column.

There was such demand for power in the populated areas south of this part of New York State that in 1922 the New York Power and Light Company decided to run powerful transmission lines through Guilderland, carrying electric current from north of the Mohawk south into the Hudson Valley, its path cutting east of Dunnsville and continuing south across Guilderland into New Scotland.

The Enterprise’s Dunnsville correspondent gave a detailed description of the 70-foot-high transmission towers set 600 feet apart in an 18-foot square base of concrete seven feet below ground. To this day, transmission lines are still running along this route through Guilderland although today they are gigantic descendants of the originals.

It took over a decade after power originally reached Altamont and Guilderland Center for electric lines to reach out to Fullers and Dunnsville. Finally, in the spring of 1927, it was announced that poles were being set in along the turnpike.

Although in 1924 the Guilderland Town Board expanded the franchise to erect poles and erect power lines on all town roads instead of being limited to the main roads, the power company wasn’t interested and those living off of the main roads continued to use kerosene lights, scrub clothes over a washboard, pump water by hand, head out to the outhouse in all kinds of weather, and carry a lantern to the barn.

If you had the money, you could purchase one of the electric generators such as the “Silent Alamo Lighting Plant” or the “Delco-Light” using a gas engine and dynamo to generate current for your house and barn. The cost was $250 (which would be $6,375 today) less 5 percent if paying cash.

Even when electric lines were run along your road, if your house happened to be set back in a lane requiring two or three additional poles to carry the line into your house, utility companies usually expected the homeowner to pay the cost of these poles, an extra expense some families were unable to afford, delaying the convenience of electricity.

It took the Roosevelt administration’s push for rural electrification to get power companies to extend their power lines out to more sparsely populated rural areas with the Rural Electrification Act of 1936.

At long last, the New York and Light Company, the successor to the Municipal Gas Company, began to wire up the outlying areas of Guilderland.

One two-mile line along “Crounse Road,” from its description probably now called Hawes Road, would be serving eight new customers, seven of them farms. A year later, 10 homes and farms along Meadowdale Road got power.

And finally, 22 years and two miles from Altamont in the last area of town to be electrified, in 1938 Settles Hill residents could finally turn on the lights.

— From the Guilderland Historical Society

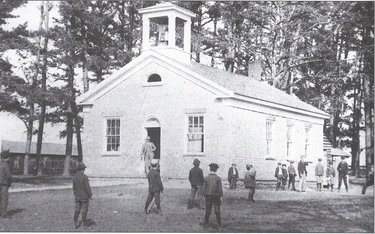

Boys at Guilderland Center’s Cobblestone School enjoyed an active game while their male teacher looked on from the doorway. Girls, who had little opportunity for active games, were probably observing from the sidelines. Both were expected to be quietly working at their seats during class time until it was their turn to go up to the teacher to orally recite their lesson.

— From the Guilderland Historical Society

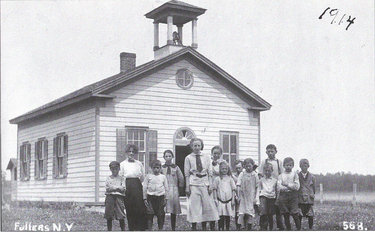

Anna Anthony posed with her students at the Fullers School. Teachers were expected to teach all grade levels with recitation and memorization considered an important part of a child’s education in the early 20th Century. Anthony, sixth from left, attended a summer session at the Oneonta Normal School after graduating from high school. That fall, at the age of 18, she was paid $15 weekly to teach at the Dunnsville School.

Life for rural Guilderland children in the early years of the 20th Century was still limited to travel by horse and wagon or train. Electricity and telephones were not yet available in their community, seeing a movie was a rare occurrence, and most children of that era had a very distinct memory of the first time they ever actually saw a car.

Children of 6 or 7 began attending one of Guilderland’s one-room common schools, although by then population growth in the communities of McKownville and Guilderland had led to the expansion of their schools to two rooms with a teacher in each room.

Altamont was by this time a Union Free School District, opening its impressive new building for grades 1 through 12 in 1902. Most of the town’s children never went beyond eighth grade, being competent enough with their common school education to farm or perform most of the jobs available at that time.

If they passed the seventh- and eighth-grade Regents (standardized tests are nothing new) to be awarded an eighth-grade diploma, there would be a special commencement ceremony.

In 1913, all eighth-graders who qualified from the “rural schools of the Town of Guilderland” graduated together at Guilderland ‘sPresbyterian Church. Quite an impressive ceremony, it opened with a prayer, followed by songs, declamations, readings, addresses, awarding of diplomas and a benediction — in all, 37 items. For parents it must have been a proud evening as each graduate had some part in what was a very lengthy program.

Altamont’s eighth-grade graduation took place in the Assembly Room of their new high school.

Special events

Certain special events of the school year relieved the monotony and were looked forward to with excitement, especially each school’s annual Christmas celebration when a special program was put on for the whole community.

Dunnsville school’s 1909 Christmas program brought out a standing-room-only crowd which heard songs, instrumental music, readings and recitations that were “carried out with intelligence and spirit,” bringing repeated cheers from the audience. The schoolroom had been decorated with a large Christmas tree in one corner.

Community Christmas gatherings and programs to which the public was invited would have gone on in all the schools in the town each year. The end-of-the-year school picnic was another tradition looked forward to by all the “scholars,” as they were always referred to in The Enterprise.

Challenges for teachers

Evaluating teachers? Regents results, the special events put on at school for the community, and their control in the classroom told people a great deal about their children’s teachers.

Discipline? Anna Anthony, as a new young teacher in Dunnsville, noticed all the children observing her closely one day and, when she eventually pulled open her desk drawer, there lay a dead mouse. A real rodent phobic, she managed to keep her cool, pick it up by the tail, drop it in the wastebasket and get on with her lesson.

But one young woman teacher at the Gardner Road School was overwhelmed by big, bad farm boys jumping out of the windows, falling off the recitation bench, in general creating chaos and preventing any learning from taking place. She was quickly replaced by a strong, tall Altamont High School senior boy who was given a temporary teaching certificate and a guarantee of his diploma to take her place and finish out the year.

Order was quickly restored when, at his arrival, he threatened to knock their heads together and legally could have done just that. Corporal punishment was the rule in those days in school or at home.