Before long, our door bells will be ringing, set off by excited, impatient, costumed children whose “trick or treat” is a demand for free candy. In the meantime, some wary homeowners fear older, mischief-making teens may pull a “trick,” resulting in vandalism in the neighborhood.

It hasn’t always been like this because Halloween was only established in Guilderland and surrounding rural towns in the last decades of the 19th Century, before becoming a popular event by the 1920s.

It all began with the prehistoric Celts in Ireland and Scotland where Samhain was the beginning of their new year. It was looked upon as a day when the dead came back to visit the living, things supernatural were about, the future could be foretold, and mischievous behavior was accepted.

When Christian missionaries came to convert the pagan Celts, they wisely allowed the Celts to keep many of their old customs as long as it didn’t conflict with Christian teachings. With All Saints Day the next day, All Hallows Eve became Hallowe’en.

With the huge influx of Irish in the 1840s and after, the name and tradition was brought along to the United States. The Scots added the happenings with the wearing of costumes that night. The customs took some time to reach out to Guilderland and other rural towns where there were few Scots or Irish.

Using the local columns of The Enterprise as a reference to get an overview of the appearance of Halloween in Guilderland, I followed the establishment of the holiday as part of the town’s cultural fabric.

In the years from 1884, when the local paper began publishing, to 1889, there is only one reference to Hallowe’en and that in a piece of fiction set in Scotland called “Spells, or No Spells.”

Guilderland was slow in joining the festivities because, while from 1890 to 1899, eighteen mentions of Hallowe’en show up, almost none of them relate to Guilderland. Feura Bush in Bethlehem reported all sorts of pranks and there were a few parties in other places.

The only mention for Guilderland was in the State Road (Parkers Corners area) column in 1895, which reported, “The ground was covered with beautiful snow, which made it quite difficult for the young men to perform their bag of tricks.”

Obviously the tradition of big boys having “fun” on Hallowe’en had spread. Guilderland Center’s St. Marks Church had a pumpkin-pie social scheduled on Hallowe’en, and there may have been a few private parties, but the town seemed otherwise quiet.

Hallowe’en happenings begin to pick up with the first decade of the 20th Century. Several churches planned Hallowe’en-night socials or suppers during these years.

Albany, home to a large Irish population, was the scene of a Hallowe’en Carnival that was an attraction to many in surrounding towns. With frequent local rail service, in 1905, Altamont “furnished its full quota of visitors to the Hallowe’en Carnival in Albany Monday and Tuesday,” The Enterprise reported.

This was not the only part of town represented there, and surely observers must have returned with ideas for future Hallowe’ens here in town.

During this time, private Hallowe’en parties given in Guilderland were beginning to be mentioned in Enterprise columns. One was at the McKownville home of William J. Knoles in 1906 when guests arrived “each arrayed in costumes representing the spirit of Hallowe’en.

Jack-o’-lanterns and pumpkins decorated the house, the first mention of jack-o’-lanterns in Guilderland. Masks or costumes were noted in two other party descriptions. However, in general, if there were other Hallowe’en activities, they weren’t noted in the local columns of the paper.

Mischief abounds

Hallowe’en’s other aspect was pranks and mischief, and at least some of Guilderland’s youth really took to that.

At different times during this decade, there was a complaint from Guilderland Center, relief from State Road near Parkers Corners that “that the young people … enjoyed themselves visiting the neighbors, but did no damage,” a comment from Fullers that Hallowe’en had come “with its usual gaieties and mischief” and word from Altamont that the boys should mind that their pranks are “amenable to law.”

It was obvious to Altamont residents one Nov. 1 that the “spooks and goblins had been out in force” the night before. Probably because in Altamont many homes and businesses were clustered closer together than in other parts of town, that’s where the most mischief seemed to have taken place.

With the coming of the decade of the teens, Hallowe’en had really begun to catch on with children becoming increasingly involved in Hallowe’en activities. A party at Guilderland Center’s cobblestone school for the “scholars” was given by their teacher, but this may have been an unusual event as school parties were almost never mentioned at this time.

A Meadowdale girl’s birthday party had a Hallowe’en flavor with decoration of witches and broomsticks. Girls who were members of the Altamont Reformed Church’s Laurel Band really got into the spirit with a party featuring jack-o’-lanterns, witches, black cats, ghosts, shrieks and groans, a skeleton, and a chamber of horrors.

Probably some adults had as much fun putting that together as the girls did being frightened. Another party brought out children dressed in many funny costumes, playing games and enjoying pranks.

There was growing popularity for adults to attend private parties, often featuring Hallowe’en decorations, costumes, games, and “stunts.” In the hamlet of Guilderland one year, parties were “numerous” with “groups of masked revelers everywhere on the street.”

Social Clubs such as the Fortnightly Club of Parkers Corners or Altamont’s Colony Club used Hallowe’en themes for meetings or parties. Hallowe’en events continued to be sponsored by churches.

Parkers Corners Methodist Church’s Social offered a seer to read fortunes and the opportunity to have your photo taken, probably for people in costume while, in McKownville, the Methodists were offering a prize for the best costume.

The evening’s activities now went beyond private parties and involved the wider community. Altamont’s children were on the streets “costumed as ghosts, spirits, elves, clowns, and various other characters.” This was very likely true in other parts of Guilderland as well.

Pranks continued to the delight of the older boys and to the aggravation of the adults. In 1910, the Altamont Village Board appointed Frank St. John as Police Officer just before Hallowe’en, using the occasion to warn the pranksters that “wanton injury to property or cruelty to dumb animals” would not be tolerated.

On more than one occasion during those years, pranksters entered the Settles Hill one-room school and created messy disorder.

The roaring ’20s

With the arrival of the roaring ’20s, Guilderland folks really got into the spirit of the holiday. Events, whether private or church-sponsored, seemed to have become more elaborate with masquerade encouraged by having prizes for the funniest or the best or prettiest or most comical costumes.

With the popularity of Halloween dances growing, there was a 1929 Mardi Gras affair (yes, it was for Hallowe’en) featuring dancing to the Castle Club Orchestra and prizes for the best costumes at Altamont’s Masonic Hall.

Children had more activities to choose from. Fullers children enjoyed a party at their one-room school, but there’s no way of telling if it was a one-time event or if children were having parties in school as a regular thing. In those one-room schools, much depended on the individual teacher.

Over 100 costumed members of Altamont’s Lutheran Sunday School were treated to a supper at the church followed by stunts such as whistling “Yankee Doodle” after eating a dry cracker. The party-goers ducked for apples and pinned the tail on the donkey.

Girls in the Laurel Band dressed as “rubes,” ghosts, witches, Indians, gypsies, and even “vamps.” Children were mentioned going door-to-door in Altamont.

The pranks!

Then the pranks! A 1920 front-page news story carried a report to Altamont taxpayers from the school board.

“On the night of October 30th last the Altamont High School building was forcibly entered and certain depredations committed to the indignation and disgust of our taxpayers. The Board was shocked by the deplorable conditions they found.”

The names of the young men were discovered and apparently the leniency of the board toward the perpetrators caused much community anger. Justifying themselves, the board members claimed, since no material damage had been done, they hesitated to bring public disgrace on the boys, and no apology was required. Might these have been the sons of some of the most prominent people in the village?

Hallowe’ens of the 1930s began with the most famous of the Altamont pranks, still talked about more than 80 years later! The boys removed half of a hundred shutters from houses along Main Street, mixed them, and then lined them up around the fence of the village park.

Part of an auto body was resting in the bandstand, while on the roof of a refreshment stand behind the A&P, a wagon was perched. Soap decorations were on many a window.

Sadly, someone’s fence was taken down and broken up. Surely pranks were taking place all over town, but the village seemed to have had the worst problem.

An exasperated taxpayer, addressing an anonymous letter published in The Enterprise to Mayor Martin in 1934 demanded that something be done about the older boys and the damage they do on Hallowe’en.

By the mid-1930s, an attempt was made in Altamont to defuse the situation by having Hallowe’en parties at school. “There were spooks and hobgoblins in the children’s annual observation of Hallowe’en,” the paper reported.

In the classrooms, there was ducking for apples, pinning the tail on the donkey, and fortune-telling. The whole idea was, if children celebrated in “a quiet way” in school, they will be taught the lesson of respect for other people’s property.

That was apparently the inspiration for those classroom parties we all remember. Whether classroom parties ended the mischief is another question!

Adult parties and socials continued to be scheduled, but for a change there were commercial venues such as the Air-O Dance Hall, which had opened in 1930, where a Masquerade Dance with prizes and novelties and music by the Five Aces was scheduled for Hallowe’en that year.

War dampens Merriment

The coming of the war in 1941 put the damper on Hallowe’en festivities, except for children, and resumed slowly after the war’s end.

In 1949, the Altamont Kiwanis Club began the tradition of community groups becoming involved in providing Halloween activities with a party, inviting all children to the Masonic Hall, beginning with a parade originating in the village park led by Altamont’s fire trucks and the Altamont High School band.

Children received noisemakers and at the hall there were prizes, refreshments, and, for the older children, movies at 9 p.m. It was a smashing success with 100 or more children taking part and the scene of overexcited children with noisemakers at the hall was described in the next week’s paper as “bedlam.”

Within two years, the Guilderland Center Civil Club and Guilderland Center Fire Department also began the tradition of an annual Halloween party.

However, the 1950s brought us the Halloween we remember and remains today. In 1950, the words “trick or treat” came into use.

A Disney Hallowe’en cartoon about Uncle Donald Duck’s three nephews — Huey, Louie, and Dewey — was called “Trick or Treat,” supposedly the origin of the familiar Hallowe’en demand.

Also at that time, candy manufacturers began Hallowe’en advertising in a big way and with that, modern Hallowe’en had come to Guilderland and all of America.

Location:

One of the most valuable Depression-era make-work programs of the New Deal was the Historic American Buildings Survey, or HABS, which recorded buildings across America, ranging from impressive urban structures to small buildings reflecting historical or regional significance.

The survey served the dual purpose of creating employment for architects, draftsmen, and photographers who would use their expertise recording antique buildings that in many cases by the 1930s were rapidly deteriorating or vanishing completely.

This mammoth project documented with photographs and drawings approximately 40,000 of the nation’s historic structures including six in the town of Guilderland.

After architect Charles E. Peterson proposed that a survey be done of American’s antique buildings in 1933, the National Parks Service established HABS in cooperation with the American Institute of Architects and the Library of Congress.

The Historic Sites Act, passed by Congress in 1935, formalized the Historic American Buildings Survey with a provision stating that the federal government would “secure, collate and preserve drawings, plans, photographs and other data of historic and archeological sites, buildings and objects.”

Professionals involved in carrying out the survey were guided by field directions established in Washington, D.C. For large or very important buildings, a combination of photographs and drawings with additional historical data was recorded while for simpler structures the HABS “short format” sufficed with one or more photographs.

Guilderland’s sites were photographed, but elsewhere both in the city and county of Albany, drawings as well as photographs were made such as those recording the Watervliet Shaker site.

Photographer Nelson E. Baldwin visited Guilderland on two occasions in 1937 to take both interior and exterior pictures of the buildings chosen to be recorded.

Fortunately so far that winter there had been very little snow in January when Baldwin visited the Freeman House in Guilderland Center, the Severson house in Altamont, the Case Tavern on Route 20 near the hamlet of Guilderland, and the “old Indian fort” now usually known by the name of the current owners as the Yezzi house on Foundry Road.

A few months later, in May, Baldwin returned, this time to Altamont to photograph the old Severson Inn, now the site of Stewart’s and the Crounse homestead on the Altamont-Voorheesville Road.

It was disappointing to find no coverage in The Altamont Enterprise of the survey or of Baldwin’s activities at that time. A brief article in July 1937 did note that the Old Friends Meeting House at Quaker Street near Duanesburg, which had been included in the Schenectady County survey, had received a certificate from Harold Ickes, the Secretary of the Interior, declaring that the building possessed “exceptional historic or architectural interest … being worthy of careful preservation.”

In 1937, all of the Guilderland buildings were private homes and it is not known if their owners received similar certificates. An advisory committee of the Historic American Buildings Survey had chosen the 700 buildings to be photographed in 16 counties of New York State and it seems very probable that Guilderland Town Historian Arthur Gregg was involved in the choices in Guilderland.

This magnificent collection of photographs and drawings is kept in the Library of Congress and is easily accessible by computer because it has been digitized. The photographs are copyright- and reproduction-free with acknowledgement to the Library of Congress.

The following are photographs taken by Nelson E. Baldwin on his visits to Guilderland in 1937 and are shown on the Library of Congress website. There are additional photographs that are not included here.

Crounse House

Frederick and Elizabeth Crounse were among the very first settlers in Guilderland, arriving at their farm in the shadow of the Helderbergs in the mid-1750s. The house that Baldwin photographed in 1937 was built circa 1803, probably adding to or replacing an earlier, simpler structure. Note that historic interior features were recorded as well as with this photograph of a key, lock, and hinge in the Crounse house. The house is on Route 156, the Altamont-Voorheesville Road, marked in front by a New York State historic marker.

Case Tavern

It was claimed that the Case Tavern was built in 1799 by Russell Case shortly before the Great Western Turnpike opened. It remained a popular tavern until turnpike traffic declined with the development of railroads. After this, it became the Case family homestead, sheltering eight generations until it was sold out of the family in 1946. The building burned in 1950 and today is the site of the former M & M Motel. The Western Turnpike Golf Course is on land that had been the Case farm adjoining the tavern. The rear views of these historic houses were also photographed.

Severson Tavern

A residence when this photo was taken in 1937, the building was originally George (Jurrian) Severson’s (Severtse’s) tavern on the Old Schoharie Road, a rest stop for weary travelers who were about to climb the escarpment on their way to the Schoharie Valley. Dating to the 1790s, the tavern was open for business at least by 1795 when Severson received a liquor license. At his death in 1813, it was the scene of an auction when his two enslaved females were sold there for $191. The tavern business dried up for his descendants in the late 1840s when the improved Schoharie Plank Road changed the route through what later became Altamont and travelers no longer passed by the tavern door. Sadly, Altamont’s most historic building was demolished in 1956 to make way for an Esso Gas Station, which in turn was razed to be replaced by the Stewart’s Shop on the site today.

Severson House

The Seversons were one of the oldest families in Guilderland, settling here in the mid-1700s. According to the 1767 Bleecker Map of the Manor of Rensselaerwyck, the Severson family was already in this location on what is now Brandle Road in Altamont. By the time of the American Revolution, at least one section of this house had been constructed by George/Jurrian Severson; it was one of the first houses erected in the area of Altamont. Note that in both interior and exterior photographs either an assistant is holding a measuring rod against the building or it is simply propped against and interior feature. In 1937, the original fireplace still retained the crane needed to hold kettles for cooking.

Freeman House

Built circa 1734, the Freeman House is considered the oldest frame house in Guilderland. It probably had been enlarged since the original section was built in the 1730s. Today called the Freeman House, it was shown as being owned by a Robert Freeman on the 1767 Bleecker map of the Manor of Rensselaerwyck. In the years after the American Revolution, it became the home of Barent Mynderse, one of our town’s leading Revolutionary War Patriots. Edward Crounse was the owner of the house and large farm that went with it in 1937. In the front view of the house, the hump of the roof of the back addition, is in actuality a part of the huge barn that stood nearby. At that time, the house was covered with synthetic brick siding, now removed, restoring the house to its original siding. It still retains its Dutch door, but the front stoop has been removed. A state historic marker is in front of the house on Route 146 in Guilderland Center.

The Old Indian Fort

According to the late town historian Arthur Gregg, the house is designated on a 1690 map as an Indian fort. While it is difficult to make out the detail, there are two narrow slits, one on either side of the chimney near the peak of the roof, that were bricked up in 1937. Perhaps at one time, when they were open, they were meant to allow the inhabitants to fire down on attackers. The house stands back from Foundry Road in a lane and isn’t visible from the road. It is considered the oldest house in the town of Guilderland and, from the late 1700s until about 1960, it descended in the Tayler-Cooper-Nott family. In the 1940s, a member of the Nott family did extensive renovations, which completely changed the look of the house from the photograph.

Location:

— Photo from the Guilderland Historical Society

Fullers with a smaller population than Guilderland Center had a much larger depot due to the business acumen of Aaron Fuller. The little community called itself Fullers Station from the time the station was built until 1897 when the name was shortened to Fullers.

— Photo from the Guilderland Historical Society

Guilderland Center’s modest railroad station was small for the size of the community. Edmond Witherwax, whose father was the station agent at the time this postcard view was made, posed for the photographer. Hurst’s Feed Mill is in the background across the street.

— Photo from the Guilderland Historical Society

A West Shore train approaches the Cobblestone Crossing, now called Stone Road. Probably because of the low volume of traffic there in the 1920s, the Public Service Commission decided against building an overpass there. Today it is still a grade-level crossing with gates and warning lights. The 1920s’ overpasses over the tracks at Old State Road and Frenchs Mills Road are now unsafe and closed to traffic.

Numerous lengthy freight trains rumble through daily, unnoticed by drivers using Guilderland Center’s Route 146 overpass, although a few may spot the trains crossing above Route 20 on the trestles at Fullers. Only a railroad buff would realize that for over 170 years trains have been passing over the same route through Guilderland.

The 1860s railroad boom brought significant adjustments to the lives of Guilderland residents when the Albany & Susquehanna Railroad was laid down through Guilderland Station (later called Meadowdale) and Knowersville (renamed Altamont) in 1863. Two years later, the Saratoga & Hudson Railroad was built through Fullers and Guilderland Center.

The Albany & Susquehanna became the Delaware & Hudson Railroad, a very busy and profitable line. In contrast, bankruptcy quickly put an end to the Saratoga & Hudson.

Robber Baron chicanery brought about the construction of a line called the New York, West Shore & Buffalo Railroad, a parallel route to rival William H. Vanderbilt’s profitable New York Central. Originating in Weehawken, New Jersey, it then ran along the west shore of the Hudson and west to Buffalo, having the potential to deliver a severe economic blow to Vanderbilt.

The old Saratoga & Hudson roadbed through Guilderland Center and Fullers became part of this new rail line.

The first train traveled through in 1883, and the line went into official operation on Jan. 1, 1884. Soon after operation began, fares were slashed in a rate war with the New York Central, duly noted by the Fullers correspondent of The Altamont Enterprise.

Fares were back to normal by August, but the fledgling railroad had gone into receivership. When the owner of the Pennsylvania Railroad was rumored to be interested in acquiring the bankrupt line, giving him the potential to undercut the New York Central, the threat forced Vanderbilt to acquire it. After becoming a division of the New York Central, the line was then simply known as the West Shore Railroad.

When new depots were constructed, Aaron Fuller was supposed to have convinced management to erect an elaborate station at Fullers, reputedly costing $6,000. There was certainly a noticeable difference between that depot and Guilderland Center’s, whose residents considered it “inadequate for the business that is done there.”

In 1887, the old track of the Saratoga & Hudson from South Schenectady to Fullers was improved to connect the New York Central main line with the West Shore to draw off freight. The tracks crossed what is now Carman Road and the Western Turnpike to connect with the West Shore, giving Fullers two separate railroad crossings.

A single track crossed the Western Turnpike just east of Fullers Station Road while the double-track West Shore crossed at grade level where the trestles are today. Fullers Station got a freight house a year later. The building was once used as a depot in Voorheesville; it was taken apart, hauled over to Fullers Station, and re-erected by station hands the same day.

New switches and additional sidings were installed at both Fullers and Guilderland Center. At first, a wooden trestle crossed the Normanskill at Frenchs Hollow, but that was rebuilt as a sturdier metal trestle to handle the increased rail traffic. The New York Central invested a great deal of money in operating this division, which also included Hudson River ferries necessary to transport passengers from Weehawken, New Jersey to New York City.

Economy boosted

Once regular rail service was established, the economy of the two hamlets and nearby farms was boosted. Working on the railroad provided new job opportunities for engineers, conductors, brakemen, firemen, station masters, and telegraphers.

Local columns in The Altamont Enterprise often mentioned the names of men who worked for the West Shore. Occasionally, men were hired on a temporary basis, such as the local men who earned $1.50 a day shoveling huge snow drifts left by the Blizzard of ’88 off the West Shore tracks.

The nameless, poorly compensated railroad workers were gangs of Italians from nearby cities who were hired to do the backbreaking pick-and-shovel jobs of maintaining tracks and roadbeds.

The West Shore benefited farmers by providing a way for them to market their oats, hay, and rye straw. Middlemen at the depots paid them for wagon loads of hay and straw, pressed it into bales, and arranged to have it loaded into freight cars and shipped to market to supply the thousands of horses in nearby cities.

October 1888 saw Aaron Fuller loading 33 cars at his Fullers Station hay barn while Clute and Tygert received 40 tons to be shipped. W.T. DeFriest advertised that he would pay $16 per ton of rye straw delivered at Guilderland Center or Fullers Station. In later years, tons of apples were shipped out.

New businesses and commercial development occurred near each depot. In both places, hay barns were erected near sidings. At Guilderland Center, a new hotel, feed mill, and coal house were erected near the depot.

For decades, the West Shore ran ads in The Altamont Enterprise, requesting information from local hotels, boarding houses, and farm families anxious to host summer boarders from the city, offering free listings in special booklets or brochures called “Summer Homes,” which could be perused by patrons seeking vacation accommodations to fit their budgets.

These summer visitors contributed much extra income to Guilderland’s farmers and hotel keepers from the 1880s to the 1920s with the railroad hoping summer visitors would board a West Shore train to get to these vacation destinations.

Wide horizons

If the coming of the West Shore had a major economic impact on Fullers and Guilderland Center, it also broadened the horizons of their inhabitants, or at least those with the cash to take advantage of the opportunities offered. Excitement and adventure beckoned when almost immediately the railroad began advertising one-day excursions.

The first excursion in September 1885 was to Saratoga over the old line into South Schenectady, arriving in Saratoga at noon, returning in the early evening. A year later, there was an excursion south down the Hudson to Iona Island near Bear Mountain in the Hudson Highlands, which was so popular that 75 tickets were sold in Guilderland Center alone and the train hauled 11 coaches for the day’s outing.

As time went on, longer and more expensive excursions were available to destinations such as Washington, D.C. or New York City. Chicago’s 1893 Columbian Exposition attracted numerous visitors from Fullers and Guilderland Center traveling there with an agent provided by the railroad to point out interesting sights along the way.

Because Ravena had a high school, it became possible for students from Guilderland Center and Fullers and other communities along the West Shore to commute daily to high school. In those days students had to pay for their own commute. Early in the 20th Century, the cost of the round-trip commute to Ravena from Fullers was $7.50 a month.

Drawbacks

Having the West Shore in their midst brought problems as well as advantages to the area. Almost immediately, it was found to be fatally dangerous.

As soon as trains began running over the new rail line, Fullers’ farmer Jacob Pangburn opined to a neighbor that one of these days someone is going to get killed by a train. Shortly after that, the unfortunate farmer was trying to get his cow off the track as a train approached. He was instantly killed when seven cars passed over him.

As the years went by, this was the first of many graphic, gory reports of deaths on both the West Shore and D & H tracks. Often at crossings someone may have been inattentive or their horse was spooked at the sight and sound of a train leading to fatal results.

Guilderland Center was a particularly dangerous crossing because of limited visibility. Sometimes pedestrians walking the tracks as a shortcut or if intoxicated were fatally hit. Many a sad tale appeared in local Enterprise columns over the years of deaths along the tracks, sometimes sadly including railroad employees. One Guilderland Center trackman was killed by a train in reverse.

A sporadic nuisance often caused by trains during the dry season were the brush fires caused by sparks given off by the locomotives. When farmer Volkert Jacobsen’s woods near Fullers burned, he lost valuable timber and nearly lost his outbuildings. Really tragic was the burning of Lorenzo Cornick’s uninsured home near Fullers “consumed by flames probably caused by sparks of a West Shore engine.”

All of these generalizations would have also been true of the communities of Meadowdale and Altamont along the D & H line, except that the D & H was a very busy and successful rail line so that, by the end of the 19th Century, 10 local trains ran back and forth between Albany and Altamont daily.

By contrast, the West Shore was not nearly so successful and provided inadequate service. Its route bypassed Albany and it was only years later that the line leased tracks from the D & H, allowing it to get in and out of that city.

In 1893, about 500 residents of several local towns along the West Shore signed a petition protesting cutbacks in the number of trains, chiefly because of curtailed mail delivery. By 1906, residents of Guilderland Center, spearheading an effort to improve service, set up a committee headed by W.B. Mynderse to appeal to the Public Service Commission to do something about the single daily local train each way that was not scheduled to make any kind of connection to reach Albany or Schenectady.

Apparently the committee was successful because schedule changes were announced by connecting a few passenger cars to regularly-scheduled freight trains, enabling passengers to make connections.

Autos replace trains

The headline of a 1916 Altamont Enterprise article, “Auto Travel Hurts Railroads,” sounded the death knell of local passenger service. The proliferation of automobiles, autobuses, and improved roads led to a major decline in passenger traffic, while trucks affected freight hauling. By the mid-1920s, local passenger service in this area was ended on the West Shore.

With increased automobile traffic, grade-level collisions with oncoming trains became a serious problem with much loss of life. One of Guilderland’s worst accidents occurred in 1919 when an out-of-town driver pulled directly in front of two coupled locomotives at the Guilderland Center grade-level crossing, resulting in demolition of the car and deaths of the driver and passenger.

Soon New York State began to force railroads to build overpasses or underpasses to end these fatalities. In 1927, the West Shore built the overpass in Guilderland Center and the underpass on the Western Turnpike at Fullers where two trestles carried trains overhead. The two depots were removed at the same time. The gravel used to raise the level of the tracks in Fullers came from Guilderland Center, loaded on rail cars and hauled to Fullers.

The New York Central fell on hard times after World War II, eventually merging with the Pennsylvania Railroad to become the PennCentral, causing the West Shore to lose its identity. Later, the old West Shore route through Guilderland Center and Fullers became part of Conrail and is now CSX.

Ironically, years ago, the D & H had far more passenger service and was a much busier freight line than the West Shore. Today, only a very few freight cars pass through Altamont weekly while endless freights pass over the old West Shore tracks through Guilderland Center and Fullers.

Location:

— Photo from the Guilderland Historical Society

Witbeck’s Hotel, originally the old McKown Tavern, stood on the Western Turnpike until it burned in 1917. The porches would probably have been added by William H. Witbeck. In the early 1970s, when King’s Service Station, which then stood on the site, was excavating for a new underground tank, part of the original foundation and burned timbers of the old tavern were found. Today, Burger King stands on the site.

— Photo from the Guilderland Historical Society

The Country Club Trolley Line reached out into Guilderland soon after the Albany Country Club opened, making McKownville easily accessible to the city, which probably helped to make McKown Grove a popular destination. The trolley also contributed to McKownville’s beginnings as an Albany suburb. Buses replaced the trolley line by the 1920s.

GUILDERLAND — A century ago, it would have been a rare Guilderland resident who was unaware of the Witbecks. The Witbecks vied with the McKowns as McKownville’s best-known family and played a very active role in community life for several decades.

Today, there is no reminder in McKownville that the Witbecks ever lived there, except that their name appears on deeds to property on certain McKownville streets.

Originally from Rensselaer County, the Witbecks surfaced in McKownville when William H. Witbeck leased the old McKown Tavern and surrounding acreage in 1884. When William McKown built the tavern in the 1790s, he also acquired a parcel of 113 acres, all of this sometimes being referred to as the McKown Tavern and Farm. The tavern was well supplied with water brought from dams on the Krum Kill put in by William McKown.

After 1884, the McKown family was no longer actively involved, and the old tavern became known as Witbeck’s Hotel. William H. Witbeck was listed as “farmer and hotel” in an 1888 Guilderland directory. The Witbeck name began to be mentioned often in The Altamont Enterprise as the hotel keeper became involved with community affairs.

A baseball fan, Witbeck began to sponsor a team. An 1897 notice in the newspaper announced, “The Witbeck baseball club will give a picnic and field day at McKown’s Grove Saturday, August 14th. There will be dancing in the afternoon and evening. Joe Marone’s orchestra has been secured. In the afternoon there will be athletic sports including a ball game between Witbeck’s and Slingerlands. A good game may be expected.”

Witbeck’s sponsorship of a hometown ball team certainly added to social life in the hamlet for many years and brought much good will as well as thirsty players and spectators to his hotel.

Another sport that became popular in the 1890s was cycling. In 1898, Witbeck began to lay out a cycle path from his hotel to the Albany line and another from the Albany Country Club to his place, providing a service for the wheelmen as well as the potential of thirsty customers for his hotel bar.

Public events sometimes took place on the grounds around the hotel, attracting a crowd; some from the crowd surely imbibed at Witbeck’s. In August 1895, the Tenth Battalion left its Albany armory, marching as far as the field adjoining Witbeck’s Hotel where the soldiers camped overnight. That evening, they performed a drill followed by “a fine concert” played by the regimental band and “witnessed by a large crowd.”

Another occasion noted in The Enterprise was the jolly crowd of “nearly 200 persons” who assembled at the hotel before marching nearby to serenade a newly married couple just returned from their honeymoon, a common custom in those days.

Although considered an astute businessman and well known in Guilderland, Witbeck never ran for office. Instead, he worked behind the scenes being very involved in local Republican politics in a day when Guilderland was dominated by the Republican Party.

He used his influence to organize and chair the nominating caucus to choose local candidates who did run for office. His hotel was always one spot where the town’s tax collector would set up to collect taxes when they were due.

Another of his local activities for many years was to serve as president of the Town of Guilderland Protective Association. This group inserted notices in The Altamont Enterprise under his name, offering a reward of $25 for the arrest and conviction of anyone stealing personal property from a member of the Guilderland Mutual Protective Association.

After Witbeck’s death in 1935, William A. Brinkman, on behalf of the board of directors of the Guilderland Mutual Insurance Association of the Town of Guilderland, inserted a notice mourning his loss and referring to Witbeck as a “faithful and wise counselor who was always ready with his time and advice.”

Benjamin Witbeck

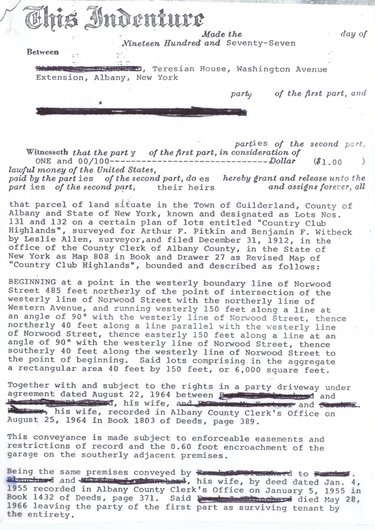

William H. Witbeck, who was the father of several children, became closely involved in business with his son Benjamin and Benjamin’s business partner, Arthur F. Pitkin. In 1907, William had purchased the hotel and, five years later, he gave title of the Witbeck Hotel and farm to his son Benjamin and his business partner, Pitkin.

Change had come to that area in the 1890s when the Albany Country Club purchased a large area of farmland near McKownville to create a posh country club where the uptown campus of the University at Albany is now located.

Soon after, a trolley line was run along the old turnpike approximately to the current entrance to the university, making it possible to commute back and forth from downtown Albany. Being adjacent to an exclusive country club, the Witbeck property had become much more valuable.

When they took over ownership, the first thing B. Witbeck and Pitkin did was to have the land surveyed by Leslie Allen and laid out in streets and lots. These streets became Norwood, Glenwood, Parkwood, and Elmwood Streets.

This proposed residential area was named “Country Club Highlands,” probably the first named development in Guilderland. A 1913 note in The Altamont Enterprise mentioned “two new houses are going up near the car line.” One of these was being built by Benjamin Witbeck.

Fire company forms

Around McKownville at this time, people began to discuss the need for fire protection. After holding an initial meeting at the two-room McKownville School, a petition was circulated, and with the resulting show of support, on April 18, 1916 a group of men met at the Witbeck Hotel to organize a volunteer fire department.

Within three weeks, Benjamin Witbeck was a member of a four-man committee to begin investigating the purchase of fire equipment. The next year, the McKownville Fire District was established, and by 1918 the department was incorporated. During the two-year period leading up to incorporation, William H. Witbeck had served as chief of an ad hoc fire company and was one of the signers of the original charter.

In 1918, Benjamin Witbeck supplied a Graham Paige car to tow the two-wheeled fire cart with its attached chemical tank. In the early days of the fire company, the department’s first apparatus was housed in a carriage house, part of the Witbeck Hotel complex, while a steel locomotive tire hanging in front of the hotel served as the community fire alarm.

Between 1918 and 1929, William H. Witbeck was a fire commissioner, and Arthur W. Witbeck, another of his sons, was a line officer. At the July 1918 Firemen’s Field Day at McKown Grove, Mrs. Arthur Witbeck took charge of the Ice Cream Booth.

Ironically, as a fire company was in the process of being organized, during the early hours of a night in the first week of October 1917, Witbeck’s Hotel went up in flames at a loss of $20,000. The three people asleep in the hotel escaped as the hotel “burned like tinder” and was quickly destroyed in spite of a bucket brigade of neighbors.

Another building on the property then substituted for meetings and tax collection and for many years operated as a small eatery after Prohibition went into effect.

Village of Witbeck?

With the numerous Witbecks so prominent in McKownville at this time, a petition circulated to drop the name McKownville, create a new identity for the hamlet, and rename it Incorporated Village of Witbeck. Opponents to the name and the establishment of village government hired lawyers to take the case to court in March 1917.

The case was known as “The Matter of the Incorporation of the Village of Witbeck, Out of Part of the Town of Guilderland.” Those opposed claimed that Benjamin Witbeck had circulated the petition for his father.

Initially a hearing was held before Town Supervisor F.J. Van Wormer with the opponents bringing along their attorneys Bookstein and Dugan. Described in The Altamont Enterprise as “a lively session,” Van Wormer declared the petition was a valid one in spite of the claims of the opposing attorney and comments by residents who were against the idea. At this, “the Witbeck clan was jubilant.”

Apparently, this whole idea had been hotly disputed in the McKownville area for months, becoming increasingly bitter as time went on. The matter didn’t end with Van Wormer’s decision.

Attorneys Dugan and Bookstein appealed to the County Court on the basis of failure to put down a $50 deposit at the time the petition was filed and furthermore had left out the word “adult” in the petition

The Witbecks had secured representation by hiring Attorney John J. Haggerty. The county judge’s verdict was to declare the petition invalid, stating a new petition must be circulated before incorporation could be considered.

The Altamont Enterprise commented that several of the original signers had now changed their minds, realizing that a village government would mean increased taxes, making it unlikely that the Witbecks would succeed. Even if they had managed to file another petition, the question would then have to be put to a vote and the opponents were not planning to give up without a fight.

This setback did not bring an end to their involvement with the community. William McKown had dammed the Krum Kill early in the 19th Century to provide water for his tavern. Beginning in 1910, William H. Witbeck set about improving the old McKown water supply, an effort that led in 1922 to the establishment of a private water company offering a steady water supply.

Using McKownville Reservoir, water lines were laid down to supply homes while the fire department paid to establish fire hydrants that remained in use until 1949.

In 1926, Pitkin and Benjamin Witbeck formally set up the Pitkin-Witbeck Realty Company to continue building houses on the streets they had laid out years before. The trolley line ended operations the year before, but had been replaced by a bus line that extended out as far as Fuller Road allowing residents to continue commuting to Albany

Houses in Country Club Hills were individually built, being of substantial construction and stylish architecture.

Early in March 1935, William H. Witbeck died at age 76 at his Western Avenue home, survived by his four sons. The Witbeck family, headed by William H., played a huge role in the late 19th and early 20th centuries in shaping McKownville into what The Altamont Enterprise described in an article at the time of his death as “one of the most attractive residential communities on the outskirts of Albany.”

Location:

— Photographs from the Guilderland Historical Society

Few women took up driving in the early days since automobiles had to be cranked to start. Here a member of Dr. Cook’s family posed in an early automobile, date and model unknown, and she may have been one of the few spunky females locally who learned to drive at that time. The Cooks summered on the farm that is today Altamont Orchards.

Martin Blessing’s cry, “Hurry out! A horseless carriage is coming by,” alerted family members to rush out front of their farm on the turnpike in Fullers. Frightened by the commotion, his small daughter peeped out from behind her mother’s skirt as the strange contraption rolled by.

Anna Anthony, recalling this event in her old age, never forgot her first sight of a car. Perhaps it had been the Locomobile Steamer Arthur Barton, living on a farm a few miles west on the turnpike, remembered as his first car, describing it as “a whooshing, bouncing carriage-like affair careening ‘madly’ down the old plank road in a cloud of dust and steam.”

Even those who had not yet seen an automobile were aware of their development after reading articles such as “The Horseless Carriage” published in a September 1899 Enterprise. As the first decade of the 20th Century unfolded, more and more attention was given to local automobiles and their owners in the pages of The Enterprise.

Owning a car in that era was not for the faint of heart. City folk seemed to become car owners before those in more rural areas and it seems out-of-towners were the first to pass through Guilderland. In 1904, Mr. and Mrs. Tompkins of New York City stopped by in Altamont while on their way to their summer home near Berne, disgusted that rain delayed them in the mid-Hudson area when the normal running time between New York City and Albany would have been only 12 hours.

A year later, they arrived with another couple in a second car headed for Berne. When, as they climbed the steep hill out of the village (now Helderberg Avenue), the Tompkins’ auto stalled, its brakes failed, and the car began rolling backward. The wife jumped out, and the husband ended up partly overturned against an embankment.

Neither were injured, the car was righted, the engine was cranked up, and these hardy motorists were on their way.

That same year, George Crounse was intending to visit his sister Mrs. E.H. York of Guilderland Center, when his car’s engine died in Gallupville, causing the humiliation of having to hire a farmer and team of horses to tow him to Altamont where he had to telephone to Albany for “a professional” to come out to fix the problem.

Not only was driving an automobile an adventure, it was an expensive one!

Early automobiles had to be hand cranked to start (electronic starters were in the future); had limited horsepower; were forced to travel for miles on wretched roads, causing frequent flat tires; and, outside of cities, there were very few places to buy gasoline or find mechanical help. A few of the very early cars operated on steam power, which had its own set of problems.

The identities of the very first car owners in Guilderland are unknown, but by 1906 drives by Altamont’s Charles Beebe and W.H. Whipple were noted in The Enterprise. There were surely others. “Auto parties” were noted at that time, passing through on their way to enjoy the amenities of the Helderberg Inn.

Sands sales

Eugene and Montford Sands got it right when they stated, “the automobile is here to stay” in one of their Sands Sons’ advertisements. Already successful Altamont grain and coal merchants, the two entrepreneurs opened an auto agency in 1907.

An early offering included, for $275, a Success runabout (a two-passenger open car) featuring a “powerful” 4-horsepower engine with wheel steer (several very early cars had tillers for steering); for $600, a Federal runabout with a 15- to 18-h.p. engine; or for a big spender willing to part with $1,250 the Model, a 2-h.p. two cylinder automobile with a removable rear seat that could carry five persons — “a wonder for the price.”

During the early automobile years, there were many companies manufacturing cars with brands that within a few years were out of business, making the brands unfamiliar today. Among the automobiles acquired by local men were Reo, Overland, Locomobile, Columbia, Brush, and Great Western.

Sands advertised others such as the Success and Model and it’s assumed that they were purchased by local drivers. Fords and Buicks were also locally owned as well.

By 1908, the popularity of the automobile was firmly established, appearing on local roads with increasing frequency. Sands Sons cleverly whipped up enthusiasm for the new technology not only with announcements and advertising in The Enterprise, but by exhibiting automobiles at the Altamont Fair where the brothers touted the merits of the new 1909 Great Western five-passenger touring car to over “200 prospective” buyers during Fair Week.

The Village and Town column in The Enterprise announced that Messrs. Clickman acquired one of them. Earlier in May 1908, the two car salesmen had focused attention on the trophy won in Menands, their Great Western coming in first for the fastest time its class for five-passenger, $1,250 cars in a steep hill-climbing contest.

Soon they were promoting a new $1,600 Great Western 30-h.p. model, which had the advantage of being converted into a gentleman’s roadster by detaching the tonneau and substituting a rumble seat. Their sales pitch ended with, “Watch out for this car as it will create a stir among auto enthusiasts.” And the really affluent man with an extra $3,500 could drive away from their dealership in a 50-h.p Great Western.

Aware that only a limited number of local men were wealthy enough to purchase a large touring car, Sands Sons introduced a two-passenger Brush runabout, claiming the runabout not only had gas mileage of 25 to 40 miles, but that a woman could drive it easily.

These two car salesmen assured prospective buyers this “very neat and easy running car” was capable of climbing any hill in the area, announcing an Albany dealer had plans to drive a Brush up the Capitol steps. New York State authorities put the kibosh on that publicity stunt and it never happened.

Many years later, it was recalled that sometimes the Brush ran well, other times the engine made a hill climb sputtering, “I think I can, I think I can, I thought I could, I thought I could ... I can’t!”

Erecting a big tent at the 1910 fair, Sands Sons continued to push the Brush, assuring would-be buyers that, if they made a purchase during Fair Week, the Sandses would give them a “special figure.” Current Brush owners were invited to use the tent as their fair headquarters.

Two people who at some point purchased Brush runabouts were Eugene Gallop, who was the mailman on a rural route, and Irving Lainhart, who delivered groceries in his Brush until 1918 when he traded it in for a Ford.

In addition to selling cars, Sands Sons also advertised that they had supplies of batteries, lubricating oils, gasoline, etc. for automobile owners and chauffeurs.

Dangers and delights

Automobile owners of the era were a versatile group, changing their own tires and dealing with simple mechanical problems, but for things more serious a mechanic was needed.

The demand was quickly met in 1907 when Mr. James Bradley opened up shop in the rear of Lape’s Paint Store in Altamont, advertising himself as an experienced mechanic who could repair automobiles.

At this time, Guilderland’s large population of upset, unhappy horses (and their owners!) were usually terrified when approached or overtaken by these noisy, smelly behemoths, especially since the roads were very narrow, putting car and horse in close clearance of each other.

Guilderland Center’s F.C. Wormer ended up painfully, but not seriously, hurt when his horses, spooked by a passing car, took off, dumping the unfortunate F.C. in the road.

As Dr. Fred Crounse was driving his auto to Meadowdale, he began passing Cyrus Crounse whose skittish horses became so terrified by the car, they rushed toward it and one ended by jumping on part of the car, “smashing some of the fixtures on the driver’s side. A few dollars in repairs made the machine as good as new,” but no mention was made whether they were Dr. Crounse’s dollars or Cyrus Crounse’s.

As automobiles proliferated, another problem became obvious. As early as 1907, the Guilderland Center correspondent wanted to know why there was no speed limit out in the country, claiming that the previous Sunday morning “there came tearing down through the Centre an auto at a velocity of speed that would put a western cyclone to blush,” showering people on their way to church with dust and grit and endangering the children.

On another occasion, an auto driven “wildly” through Guilderland Center struck and killed Seymour Borst’s pet dog. Again a call was made for more strict laws against those “speed fiends who rush madly down our streets.”

Automobiles had become a permanent part of childhood experience. Marshall Crounse, 9-year-old son of Dr. and Mrs. Fred Crounse, ran in front of a car while on vacation with his parents in Florida and was knocked down with at least one wheel rolling over his legs just below his hips. Miraculously escaping serious injury, Marshall was fine by the time of his family’s return to Altamont.

Ten other children had a more positive experience when Mrs. David Blessing, their Sunday School teacher, arranged for Montford Sand to cram all 10 into his big touring car for a drive to a picnic at Frenchs Hollow.

The danger of fire became evident. A very expensive touring car driven by summer-cottage owner Gardner C. Leonard’s chauffeur burst into flames a mile-and-a-half east of Altamont.

The chauffeur threw himself out of the car just in time, for when the fire was out, the only thing left were the two front wheels. The frames of those early cars were of wood, causing them to burn rapidly once the gasoline was ignited.

When another auto fire destroyed a vehicle on the Western Turnpike in what is now Westmere, it was noted the owner had insurance.

“Death in Auto Accident” headlined the most tragic fire in 1911 when Mrs. William Waterman, out with her husband for a drive near Altamont’s Commercial Hotel on Main Street, suddenly screamed she was on fire. Her light summer clothes quickly blazed up, resulting in her death the next morning.

Although The Enterprise said the cause of the fire was gasoline, the car itself didn’t burn. Many years later, a recollection of the incident claimed the car was a Locomobile Steamer, an early car where paraffin or naphtha provided the fuel for the fire to heat the water to make steam to power the automobile. These impractical cars quickly went out of production.

One August 1911 morning, William Whipple, driving the Sands’ autotruck, pulled out of Altamont carrying Montford Sand in the passenger seat. While traveling down “church hill” past the entrance to Fairview Cemetery (now Weaver Road), the autotruck encountered two women approaching in a horse-drawn buggy.

The skittish horse panicked, jumped into the ditch, and overturned the rig, throwing the women out. Seeing their plight, Sand immediately leaped out of the autotruck, stumbled and fell, striking his head. Unconscious, he was carried back to his Altamont home where he died hours later.

The automobile by 1911 was an everyday part of local life whether for pleasure or for work. The dangers of automobile ownership had already become apparent and it was a tragedy that Montford Sand, one of the brothers who did the most in the very early days to popularize the automobile in Guilderland, died in an automobile-related accident.

— Photo from the Guilderland Historical Society

Guilderland Center’s service flag hung on a special frame above the fire department’s locomotive ring that once called out the community’s firemen to fight a fire. It stood just outside the firehouse in the “old town hall” building on the main street, now Route 146, opposite the Cobblestone School.

— Photo from the Guilderland Historical Society

Some historically minded person not only snapped these photos to record the parade and dedication of Westmere’s Honor Roll, but in addition jotted explanatory notes on the back side of each snapshot. Marching in their dedication parade on Route 20 in 1943 were the Westmere Fire Department Ladies’ Auxiliary and the local Boy Scout troop.

The spring of 1942 found the United States at war with Japan and Germany. Japan, rapidly expanding its empire in the Pacific, was seemingly unstoppable.

The Japanese had not only had battered the American fleet at Pearl Harbor months before, but by early April had forced the surrender of American troops at Bataan in the Philippines, followed a month later by their taking Corregidor. Coming closer to our mainland in June, the Japanese landed in the Aleutians off the coast of Alaska.

In Europe, Adolf Hitler’s armies had occupied most of the continent and were sending endless bombing raids in an attempt to pound Britain into submission. Hitler’s June invasion of the Soviet Union was rapidly advancing. With ever worsening news from abroad, these were dark days for Americans.

In August 1940, with the threat of war looming, President Franklin D. Roosevelt called reservists and National Guard members to active duty, and that September Congress passed the first peacetime draft in our history, for men between the ages of 21 to 35.

By the spring of 1942, every community saw large numbers of its young men volunteering or being drafted. As the war went on, the draft expanded its classifications.

Local families whose sons and sometimes daughters were in the military hung rectangular service flags in a window, the blue stars representing their family members in the military and, as the tragic toll of war mounted, gold stars for family members killed in the war.

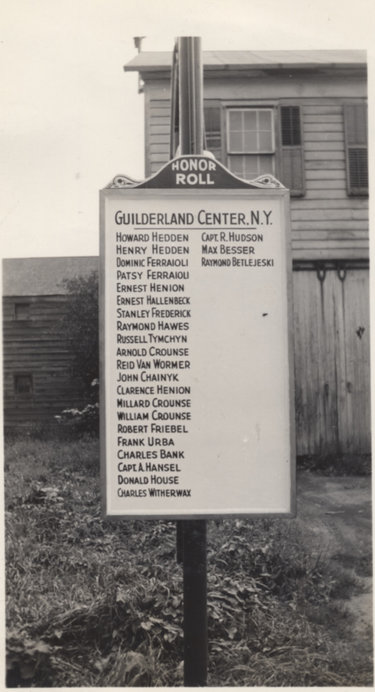

Communities, feeling the absence of so many of their young men and wanting to recognize their service, began displaying service flags and erecting wooden plaques or honor rolls in a public place for all to see. The honor rolls listed the names of all the local men and the occasional women who were in the armed forces.

Private Orsini MIA

as Altamont honors servicemen

The May 29, 1942 Enterprise had two front-page headlines, one reading “Honor Roll Plaque To Be Placed in Park, Plan Parade, Addresses,” while adjoining it was the lead headline “Altamont Man In Corregidor Area, When Island Fell/ War Dept. Waits Word From Japanese For Names of Prisoners Taken.”

The young Altamont man was Private Millard Orsini. Scheduled for June 21 in the park, the committee had already begun planning a parade and dedication ceremony, including all ages and groups, particularly recognizing the mothers of servicemen by seating them at the front of the dedication ceremony.

With the fate of the young Orsini serviceman hanging in the balance, Altamont’s dedication was probably the most emotional of all the local dedications.

On dedication day, the parade started from the fairgrounds down Grand Street to the Main Street, right on Lincoln Avenue, over to Western Avenue and then across Maple Avenue past the reviewing stand there and over to Depot Square and the park. Along the route, all the homeowners had been requested to display their American flags.

Four divisions marched in the parade, the first including Grand Marshall John Walker, a World War I veteran who had fought with the British and was a member of the Helderberg Post American Legion, followed by the ceremony speakers, village trustees, color guard, the British Empire War Veterans Kiltie Band, American Legion and its auxiliary, Red Cross members and their ambulance, Army jeeps and their representatives.

The second division had the Altamont Fire Department members and auxiliary and other groups. The third division was headed by the chief air-raid warden and included the Altamont High School Band, air-raid wardens, and fraternal and civic groups. The fourth division was led by the chairman of the local Boy Scout committee, leading Boy Scout and Girl Scout units.

Once at the park, the large honor roll plaque was unveiled and dedicated. It listed 52 names with space for additional names to be added as the war continued.

The ceremony began and ended with invocation and benediction by Altamont’s two Protestant ministers with additional words from a LaSalette priest. A local woman sang “America,” followed by a welcome from the village mayor.

The actual dedication was led by Margaret Rickard and Ken Orsini, assisted by Margaret Orsini, Mary Rau, and the color guard. After the president of the fire department read off the names on the honor roll, General Ames T. Brown was the principal speaker. Mothers of servicemen were presented with service pins at the end of the ceremony.

Hamlet has plaque

on church lawn

July 1942 brought other honor-roll dedications in Guilderland’s communities.

Hamlet of Guilderland residents gathered on the lawn of the Presbyterian Church for the dedication of their honor-roll plaque, listing the names of 26 men in that election district. Both the plaque and a service flag with stars representing the 26 men had been erected on a corner of the Magill property next door to the church.

Today we know this as the Schoolcraft House, but the Magills lived there for many years in the 20th Century. There was no parade, but a dedication service was held in front of the plaque.

Opening the program, the orchestra of the Federated Sunday School played a march, followed by an invocation given by the Federated Presbyterian Church’s Rev. DeGraff and two solos, “America” and “Recessional” were sung.

Guilderland Center’s Rev. W.D. Worman of St. Mark’s Lutheran Church offered a prayer, then remarks were made by Aaron Bradt, a Spanish-American War veteran, and Rev. DeGraff offered a prayer.

The Home Bureau presented to the community a service flag that was accepted by Guilderland’s fire chief. To one side of the honor-roll plaque had been erected a flag pole to hold an American flag with the service flag hanging horizontally.

Next, many community organizations marched to the honor-roll plaque: Boy Scouts and Girls Scouts, a color guard, Sunday School children carrying flags, relatives of servicemen, Home Bureau members, the Red Cross, the Order of Red Men and their Pocahontas auxiliary (this was a fraternal organization based in the hamlet).

Next, the director of the Girl Scouts, assisted by her brother-in-law, a naval storekeeper third class, unveiled the honor-roll plaque. A Boy Scout presented the American flag and a Girl Scout presented the 26-star service flag, which were then raised by a member of the Order of Red Men. The ceremony concluded with Rev. Worman offering benediction.

Parade starts

Guilderland Center ceremony

The next weekend, Guilderland Center dedicated a service flag sponsored by its fire department. The event began with a parade headed by the 50-piece Roesselville Band (this high school preceded Colonie Central High School).

As he had been in Altamont, World War I veteran John Walker had been invited to be Grand Marshall.

In front of the Cobblestone School, an invocation given by Helderberg Reformed Church’s Rev. James Moffit was followed by a solo of “America,” a welcome, then the guest speaker Past Commander of the Albany County American Legion, followed by a few words from Fr. Dillon of LaSalette Seminary.

The main address was made by Col. John Chambliss, the officer in charge of the Voorheesville Holding and Reconsignment Point (the official name of the Army Depot).

Then the service flag was presented and the names of those on the roll of honor were read, a bugle call to the colors sounded out, and the audience recited the Pledge of Allegiance. The flag was formally accepted for the community.

Then auxiliary members of the Guilderland Center Fire Department presented service pins to mothers of servicemen and the dedication service culminated in the singing of “The Star Spangled Banner” and a benediction offered by Rev. Worman of St. Mark’s Lutheran Church.

In Westmere: A promise to

‘have a good America waiting’

The community of Westmere dedicated its own honor-roll plaque in June of 1943, recognizing the 90 men from that fire district serving in the armed forces with a parade on Route 20 and a ceremony at the Westmere firehouse.

It was noted that this was the first time in history a parade had been held in Westmere.

One of the speakers was the Albany chairman of the Joint War Veterans’ Advisory Board who looked to the future saying, “Let us promise those men in uniform that we will have a good America waiting when they return … .”

The president of the Albany Chamber of Commerce also spoke, warning the present war is “an all-out struggle for our way of life.” Reverend Carothers had opened the ceremonies with a prayer and town Supervisor Earle B. Conklin of McKownville also spoke.

Honor rolls grow

In Altamont, July 4, 1943 was marked with a parade and rededication of their honor-roll plaque, which was so filled with names that two side panels had to be added to provide space to list nearly three times the number of the original names.

The list given in The Enterprise article included one man who had died in service; one woman; and, next to Millard Orsini’s name: “held prisoner by the Japanese according to report of the International Red Cross.”

One of the seven Orsini brothers who fought in World War II, Millard survived the war and came home to Altamont. The American flag he fashioned as a prisoner of war, risking his life to do it, is now displayed at Altamont’s Home Front Café.

Two flag poles had been donated, one for an American flag and the other for a service flag erected on each side of the now expanded plaque. A man volunteered to repaint the weathered names on the original plaque and add the new names.

The rededication ceremony was similar to previous ones with clergy, civic groups, the Altamont High School Band, and officials taking part. Later that year and again in 1944, notices appeared urging anyone knowing of an armed-forces member from that vicinity not listed to make officials aware so his name could be added.

In 1944, Guilderland Center folks were raising money to enlarge the service plaque, while in Guilderland the Home Bureau was raising money to get new flags and enlarge its honor-roll plaque. If McKownville had an honor roll or service flag, there seemed to be no mention of it in The Enterprise.

These patriotic dedication parades and ceremonies served not only to honor and support the men and women in the armed forces, but also to raise morale on the home front. As members of the community came together, the ceremonies fueled their determination, no matter their ages, to do what it would take to win the war.

Location:

— From Mary Ellen Johnson

This engraving of an oil well illustrated a share of the French Creek Petroleum Company, incorporated in New York State in 1865. It illustrates an oil derrick, probably much like the structure erected on the Severson farm in Knowersville in 1886. In the place of the oil storage drum shown, there would have been a shed to protect the engine from weather. This stock was made out to Annie Trainor, a young Irish servant girl who worked for a wealthy family in West Haverstraw, New York during the 1860s. Probably it was a gift given to her from the family, but unfortunately the company was no more successful than the Armstrong Company was in Knowersville. Mary Ellen Johnson, Annie Trainor’s great-granddaughter, still owns the share of stock.

Once upon a time, a tiny village dreamed of a natural-resource discovery that would lead to growth, development, and prosperity. The Dec. 12, 1885 Knowersville Enterprise headlines summarized it all: “A Great Scheme, A Plan Which May bring Untold Wealth to Knowersville, Hunting For Natural Gas Wells Among The Helderbergs.”

Imagine the astonishment, excitement, and probably skepticism and controversy in the little hamlet when Mr. W.H. Granby, representing the Pennsylvania Gas Company, showed up in town to announce that the company intended to drill at the base of the Helderbergs for oil and natural gas, chiefly gas.

Based on their theory that the Knowersville area was directly east of that part of Pennsylvania where gas and oil had been found only 26 years earlier, the company, also known as Armstrong & Co., proposed to lease local mineral rights to five- or six-thousand acres. The proposed leases included a nominal sum to be paid to the property owners, including the promise of “a fair percentage of the profits.”

To prevent any rival companies from drilling nearby wells in the event of a productive well being discovered, the company felt it necessary to lease such extensive acreage from the local farmers.

Enterprise Editor J.D. Ogsbury noted the many advantages that would occur with gas’s discovery. Property would be quadrupled in value, then followed by extensive development in the area, raising the population to “more desirable proportions.”

The nearby cities of Albany, Troy, and Schenectady would demand this “wonderfully cheap new fuel” and much of the money they spent for it “will find its way into the opulent pockets of the sturdy farmers around us.” Ogsbury couldn’t imagine why any landowner would refuse to sign one of the leases. He concluded by quoting in detail the favorable opinions of prominent men in the community, all in favor of signing the leases.

By the end of February 1886, Mr. Granby returned after having obtained leases to 10,000 acres northwest of Catskill, now prepared to sign up landowners in the Knowersville area. The Enterprise added, “The company, we learn from various sources, is most reliable, and we are well satisfied that no one need hesitate a moment to execute a lease with them … With a gas well in successful operation in Knowersville there would be such a rush of manufacturers to this place as would give it a large city’s growth in a very few years.”

By early March, mineral rights to two- to three-thousand acres had been obtained from farmers coming in to sign leases, but “some are holding back” (italics in the original). Pressure began to be put on the skeptics who refused to be rushed into such a big decision.

Trying to push them, the newspaper claimed only the Pennsylvania Company had the capital to finance the $8,000 it would cost to drill the well and the $100,000 capital to utilize the gas if it were discovered.

Within a few weeks, Mr. Granby announced that considering almost all the land needed had been leased, the order for drilling equipment had been put in. However, there were still a few stubborn holdouts refusing to sign, and increased pressure was put on the reluctant signers. The Enterprise warned that the company might abandon its efforts as a result of their unwillingness to commit.

The next week’s edition was relieved that “Mr. George Dutcher, after standing out some time, leased his farm to Mr. Granby and so have others since our last issue,” giving his company control over 5,511 acres. At this stage, Mr. Granby was busy negotiating for timber necessary to build the drill framework.

Two weeks later, Mr. Granby’s efforts were rewarded by additional leases being signed. The drilling equipment and timber were on order. In the meantime the drilling site had been selected.

Earlier, The Enterprise had speculated that the drilling would take place either at the base of Indian Ladder or in Alexander Crounse’s gully, but finally the part of the Severson farm just back of the village was selected as the drilling site (in the area of present-day Severson Avenue). Early May was the target date for drilling to begin.

Impatience was growing the next week when Mr. Granby was called out of town to meet with gas-company executives and confer with the men who would be doing the drilling. Returning, he assured locals that the materials for building and operating the derrick would soon reach Knowersville. Enterprise readers were told “next week” would see real activity begin.

Next week became two weeks, but finally the lumber having arrived, was unloaded from the (railroad) “cars.” Skilled workmen were due to arrive any day, then “in two or three days.” Finally, at the end of May, Mr. Granby and his workers were preparing to really get started, but unfortunately the rig iron and other materials were still in transit.

Early June brought great excitement as at last the derrick was erected. A carload of drilling components had come and drilling was expected to begin in days, but first it was necessary to build an engine house to protect the machinery from the weather. All that was needed now was the engine.

Drilling had not yet begun when, in the last week of June, Mr. Granby announced that he had discovered a spring two miles from Knowersville that he refused to identify more closely. He claimed to have noticed traces of sulphur, bailed out the spring, inserted a pipe down a few feet, lit a match and “we soon had a tiny flame of gas.”

Drilling begins, hopes high

Singed leaves and branches were displayed as proof for skeptics. Soon after this teaser, the engine, drills, and four skilled “drill men” arrived. Work could finally begin! It was now the end of June.

The arrival of the big day soon found the workers drilling through solid rock. At press time, The Enterprise reported they had drilled down 100 feet still pushing through solid rock, but soon another complication interfered with progress.

In 1886, the engine powering the drill was a steam engine requiring a steady supply of water. Quickly it became necessary to sink a second well in an attempt to find an additional water source. As it was, water was being carried in by the barrelful, slowing drilling considerably. The water problem dealt with, drilling resumed, reaching a depth of 300 feet.

“Gas At Last, A Big Flame Is Burning In The Ravine” were the excited headlines in the July 17 Enterprise. At the depth of between 500 and 600 feet, a vein of gas was struck that flamed up in the nearby ravine where Mr. Philley’s picnic grounds were located, “a novel and interesting sight and justly caused considerable excitement among our townsmen … .”

The drillers themselves were surprised at finding gas at such a depth and intended going down to 1,500 feet, seeking a stronger flow of gas. Editor Ogsbury bragged, “…it is now reasonably certain that Knowersville is destined to become the centre of a great gas producing region.”

Drilling continued to a depth of 1,300 feet in the quest for the sand rock where drillers could expect to locate gas. A week later, a depth of 1,600 feet had been reached, but having run out of rope, drillers were forced to wait for the arrival of additional rope to allow them to get down to 2,200 feet.

In the meantime, State Geologist Professor Hall made the pronouncement that any gas found so far was useless marsh gas (methane), and no supplies of natural gas would be found. The Enterprise pooh-poohed this, calling Professor Hall’s comments, “bosh.”

With the arrival of additional rope, drilling reached 1,900 feet, but it was slow going, half the progress as formerly. The drillers were not yet discouraged, having run into similar rock stratum elsewhere.

Next, the gas company was forced to make further investment to repair the derrick, replacing the original wheel with a much larger one that “greatly supplements the power of the engine, and they are ready for heavy drilling.”

After two months of unsuccessful drilling, it was now the end of August. A week later, a report that one of the shafts connected to the derrick’s large “band-wheel” had broken, resulting in suspension of drilling for several days.

It was no surprise that The Enterprise reported people in the vicinity were getting discouraged with the unsuccessful well, but quoted the highly experienced crew boss who said, “he was losing confidence in the present well, he was confident that there was an abundant supply of gas within a short distance.” But mid-September brought fresh encouragement when the drillers got through the black rock, hitting gray “lime rock” at a depth of almost 2,000 feet.

Drilling stops, dreams die

Three weeks later, drilling activity at the well had stopped. Knowersville’s dreams of growth, wealth, and importance came to an end shortly afterwards.

News spreading in the village and vicinity that the well would be exploded attracted people to the site of the well to witness the event. A slight jar was felt and, as expected by the drillers, this last-ditch effort brought no sign of gas.

The 12 empty cans with glycerine remnants were then taken back to the woods to be exploded. “The report was terrific” and at first onlookers thought it was from the well itself, but were disappointed. The company then moved on to the Knox farm of James Finch to try again.

The only benefit to come from the gas exploration was that the farmers who had leased their land to the company earned a rental payment of 12 ½ cents per acre, paid in early November by Messrs. Armstrong, Hindman & Co. who then dropped the leases.

The Enterprise was forced to return to reporting more mundane events in the little village, which grew and prospered at a slower rate than if their natural gas dreams had come true!

Location:

Key to the Knowersville section of the 1866 Beers Map of Guilderland: l. Bozen Kill; 2. House of Dr. Frederick Crounse; 3. Knower Homestead; 4. Hotel of James Keenholts (Inn of Jacob Crounse on the State Historic Marker); 5. Hotel (Was this one later run by Jacob Crounse as competition for James Keenholts who was now in the original Crounse Inn?); 6. Store (probably the one run by Jacob Crounse containing the post office); 7. Blacksmith shop; 8. Probably a wheelwright shop; 9. Albany-Schoharie Plank Road, originally the old Schoharie Road, now Route 146 until it branches off to the right as Schoharie Plank Road; and 10. Modern day Gun Club Road. Note that by 1866 the railroad had been in operation three years and buildings had begun to appear west of the original Knowersville.