Tell the truth, even if it means standing alone

After President Jimmy Carter died, the Museum of Political Corruption in Albany wanted to honor him, said its founder and president, Bruce Roter.

In 2017, Roter had received a handwritten note from Carter when he sought responses for a book on ethical leadership.

“His message was simple, yet powerful,” Roter told the crowd of about one-hundred that filled a lecture hall on April 16 at the University at Albany.

“The root of ethical leadership is to tell the truth,” Carter wrote.

That message, which Roter posted, resonated with Asha Rangappa and ultimately brought her to the university last month to share her thesis on the mechanics of complicity, which she has been working on for the last nine years.

She described herself as a former FBI agent who likes to find patterns as she did conducting foreign counterintelligence investigations, and also as a “gatekeeper for the legal profession” as she worked for 12 years as the dean of admissions at Yale Law School.

“Complicity,” said Rangappa, “is both a pattern of behavior and an organizational system.”

She explained why people become complicit in misconduct and corruption in the hope her listeners would apply that framework to their own lives and organizations.

As she spoke, we thought of a recent story we had published on school bullying and of a series of stories we wrote last year on issues a public library faced with unfounded charges of racism. We believe some of the remedies Rangappa suggested would be applicable to those and to other local issues The Enterprise has covered.

Further, she made applications to the ramifications of complicity for democracy, something now confronting all of us.

Rangappa started her lecture by projecting familiar faces of people in the national news, among them: Elizabeth Holmes, the biotech entrepreneur who founded a seemingly miraculous blood-testing company but was convicted of fraud; Derek Chauvin, a police officer convicted of murdering George Floyd, kneeling on his neck as Floyd cried out, ‘I can’t breathe”; Jeffrey Epstein, “a billionaire who ran the sex trafficking Ponzi scheme”; Richard Sackler, president of Purdue Pharma, developer of OxyCotin, sued for his role in the opioid epidemic; John Geoghan, a priest accused of molesting 150 boys, murdered in prison; and Christopher Duntch, a Texas neurosurgeon who maimed dozens of patients before his license was finally revoked.

“These are the least interesting people to study,” said Rangappa, “because these individuals are entirely predictable and they're also likely beyond rehabilitation.”

What does interest her is the “supporting cast of characters” that allowed them to continue their behavior for so long. She created a taxonomy for that cast that spans sectors of society including corporations, government, religious institutions, sports, and academia.

Rangappa depicted it as an inverted pyramid with a very small “corrupt core” perched atop its wide base. That wide base is made up of “active enablers.” Beneath the enablers are a swath of “amoebas,” and finally at the bottom, the small pointed tip, are the “truth tellers.”

Those in the small, corrupt core are, broadly speaking, motivated by power, said Rangappa. “These people typically do not have a functioning moral compass … Their reality is what they create ….,” she said. “They are very vindictive and will use their power to keep people in line, and require unconditional loyalty.”

Sometimes active enablers are loyal to a person; other times, to an institution — like a cardinal trying to protect the reputation of the church by reassigning a molesting priest, or a hospital quietly passing along a doctor who botches surgeries to protect a hospital.

Rangappa also diagrammed a “pyramid of choice,” where two people have a chance to cheat on an exam critical to their advancement. The one who chooses to cheat comes to rationalize that “everybody cheats.” That justification then informs his next choice.

“So you can either strengthen your moral compass or you can start going astray,” said Rangappa.

In recruiting individuals for counterintelligence work, she said, candidates would be asked “for some small favor” and the FBI would “wait to see if they reported it.”

“My job as an agent was just to help them continue to feel like this was their own choice and that there was nothing wrong with what they were doing,” she said.

In the end, Rangappa said, “The person who cheated does not think that they’re a bad person.”

Active enablers are driven by opportunism and ambition and “quickly come up with a rationalization that will comport with who they believe themselves to be … a good person, ethical, morally upstanding.”

Rangappa listed “hacks” for moral disengagement: justifications like the end justifies the means; euphemistic labels: “enhanced interrogation techniques” sounds better than “torture”: advantageous comparison, choosing something not as bad; displacing or diffusing responsibility as in “I’m just doing my job”; or reframing the effects by minimizing consequences, for example, saying slaves were treated well, or dehumanizing victims as cockroaches or snakes, or attributing blame to the victims.

She mentioned doctors aggressively pushing OxyCotin prescriptions, and showed a video of police officers walking by a prostrate protester — one officer briefly stopped as if to help, but then hurried on with his fellow officers.

“The bystander effect is when people take their cues from social norms and are heavily influenced by what the group around them is doing,” said Rangappa.

Rangappa finds the amoebas, the shape-shifters, the most fascinating. “They conform to whatever is around them,” she said, whether it is strong ethical norms or pressure in the other direction.

“The motivation here is self-preservation … I want to keep my job, I want to keep my social status, I don’t want to stand up, I want to keep my tribe.

“They are more aware of the choices to be made but they are paralyzed by fear, specifically the fear of retaliation, expulsion from the group, which conforms with the demand for loyalty.

“Their coping strategy is to look the other way,” said Rangappa.

Finally, there are the truth tellers, said Rangappa, going over their characteristics, including: a duty to speak the truth, to be frank and tell all they know, to speak despite the risk, often facing danger; a duty to higher principles rather than to a person or institution or tribe; a sense of agency, believing that what they say will make a difference; a high degree of empathy — they cannot justify wrongdoing to others by minimizing it; and they are willing to pay a price, to lose something they hold dear.

“I believe that, apart from the most pathological people, truth tellers can be made. And the people who were even actively complicit can be reformed,” said Rangappa.

She gave the example of Oscar Schindler, the German industrialist and member of the Nazi Party, who started out wanting to make money but over time developed awareness and willingness to change and took action to save the lives of over 1,000 Jews during the Holocaust.

“How do we flip the system around and make it one that’s led by truth tellers?” asked Rangappa. “And how do we incentivize and nudge amoebas specifically? I think active enablers can become truth tellers.”

First, she said, you need a clear code, a set of rules on how people in a particular organization or country should behave. Second, you need an enforcement mechanism that ensures compliance with the code by monitoring, investigating, and determining violations and imposes penalties for them.

Finally, you need a channel for sunlight, an avenue that allows for transmission of information or violations of the code to reach the enforcement mechanism.

One of these three components is missing when you see a system of complicity, said Rangappa.

These three are vital not just for organizations but for individuals, she said. On the individual level, said Rangappa, “Your code is your principles, your values, your beliefs. Your enforcement mechanism is your conscience,” which can make you uncomfortable as you feel guilt or shame or remorse or regret.

“Then the sunlight gets to the courage piece of this,” she said. “The truth tellers — what they are doing is actually bringing things out into the light.”

Applying the model to a democratic government, Rangappa said the code is our laws, the enforcement mechanism is our independent judiciary, and our sunlight is our civil liberties — the free press, the right to protest.

In modern dictatorships, said Rangappa, military coups are out; legal coups are in. “We now have authoritarian systems that use the law as a veneer to maintain the pretext of legitimacy …. Called electoral autocracy, it’s basically a paper democracy ….

“Active enablers and amoebas are placed in positions of power, and investigations, prosecutions, and court decisions are used to punish opponents,” she said, noting, there is retaliation against truth tellers and information channels are controlled. “Basically, the truth-telling is punished.”

Rangappa said, “I don’t really have good news on this front at this moment.”

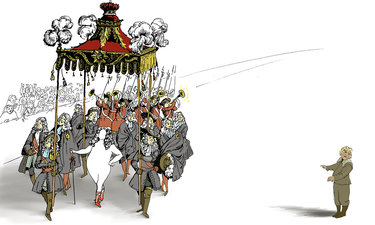

Nevertheless, she gave us a way forward — to flip her taxonomy triangle upside down: “Principled leadership” is the small core at the top, replacing the “corrupt core,” and it is perched atop a wide base made up of truth tellers. Amoebas still make up the middle — “they’re going to go in the direction of least resistance” — but the tiny pointed tip at the bottom is made up of “active enablers.”

Getting to that inverted triangle with the truth tellers at the top won’t be easy because as Rangappa noted, “We are in a place where we have lost the transcendent principles that bind us.”

To transcend our current political polarization is tough with splintered media espousing separate views as truth, but we need to agree on certain essential values.

Going back to our founding documents — the Declaration of Independence, the Constitution — would be a good starting place.

A constitutional scholar, Julie Novkov, dean of the University at Albany’s Rockefeller College of Public Affairs and Policy, who introduced Rangappa, said, “I study institutions and how they interact, and we have seen our national institutions struggle to respond to this crisis.

“Ultimately, we are finding that it is up to us — ‘We the People,’ of the Constitution — to meet this moment with knowledge, integrity, and energy.”

All of us are, no doubt, amoebas in some aspects of our lives but each of us needs to make an effort — even in small ways — to step outside our comfort zone, perhaps step away from our tribe, to confront what we’re afraid of losing, to do what our conscience tells us is right.