Play time is essential to students’ learning

A child’s work is play.

Play is how children learn about themselves and how to make their way in the world — how to lead, how to follow, how to imagine a future, how to get along with others, how to empathize, how to make rules and break rules, how to be human.

Last year, the United Nations created a new International Day of Play, June 11, citing global research that roughly three-quarters of children don’t believe adults take play — and how it can help them learn — seriously; close to 80 percent say adults do not think play is important.

Last week, Melinda Person, president of New York State United Teachers, hosted a press conference to push state legislation that would study recess at schools.

Person brought her son, a Guilderland third-grader, to the event.

“This is the first time he’s ever asked me to come to a work event,” she said. “And honestly that says everything because our kids, they know what they need … They’re telling us loud and clear that they want more time to play, more time to be kids, to run, to imagine. Somewhere along the way, us adults forgot about how important it is.”

Jude Person stepped to the microphone himself to say, “I think we should have more recess, not just when there’s extra time, but every day, no matter what. Even just 15 more minutes a day would make a huge difference for us. When I come back to class, my brain feels ready. It’s like pressing a reset button. Without enough recess, my brain feels tired and slow.”

His classmate, Cartier Appiah, added, “When I play tag or Gaga ball, I feel strong and good about myself.”

Senator James Skoufis, a Democrat from Orange County, has proposed a bill for a statewide study of recess practices in kindergarten through sixth grade to identify disparities and gaps in recess time.

“If you want physically fit kids, you need recess,” said Skoufis at the May 20 press conference. “If you want emotionally developed kids, you need recess. If you want kids who are capable of interacting and being social, you need recess. And, yes, if you want kids who are able to go back to a classroom and feel energized and refreshed … you want more recess.”

He concluded, “The first step is we’ve got to collect the data.” The ultimate goal is to require schools to allot children 30 minutes a day for recess.

The experts who spoke on May 20 emphasized those same points.

Early childhood educator Teresa Marie Anna Bello noted that, in the 1970s, children enjoyed on average 90 to 120 minutes of recess each school day but now many districts have cut back or eliminated recess. Citing a 10-percent improvement in academic performance at schools that have recess, Bello said, “Recess is not just a break; it is learning in disguise.”

Maria Gonzalez, a Rochester school psychologist, cited “an alarming increase of mental-health disorders in our children that have reached epidemic levels. Our kids are not OK,” she said, noting that, in neighborhoods were “violence is very real,” many children cannot play outside.

Lydia Rivera-Warr, who lives in inner-city Rochester underscored that point, describing how her 5-year-old daughter was playing outside with other neighborhood kids when she witnessed a drive-by shooting.

“What should have been a peaceful and joyful moment turned into something traumatic,” said Rivera-Warr. “That fear stayed with her. It stayed with all of us after that.”

Besides the improvement in schoolwork, Gonzalez said of play, “Children learn about patience and conflict resolution by negotiating and learning to compromise. Children learn to wait their turns, an extremely important skill to have when so much in our society promotes instant gratification. We need to let children be children.”

Melinda Person said that even kids in suburbia, where safety isn’t an issue, are less likely these days to go outside to play with “screen addiction and social-media addiction.”

Person spearheaded NYSUT’s successful campaign earlier this year that ended with the governor’s proposal for a bell-to-bell ban for students’ use of cellphones in school, which will go into effect in September statewide.

Governor Kathy Hochul started her statewide “listening tour” on the issue at Guilderland in the summer of 2024 and came back to Guilderland’s Farnsworth Middle School in January to launch her campaign for a statewide smartphone ban.

We admire Person’s pluck and think she is right on both issues.

But what is needed is a sea change in our societal values — values that cannot be legislated.

Schooling across our nation has become test-driven. In 2002, federal legislation dubbed No Child Left Behind focused on raising test scores, leading schools to cut play time for instructional time.

In 2009, with the Common Core initiative, education shifted from a whole-child approach to a more narrow focus centered around passing standardized tests, partly to maintain standing with the Department of Education.

Anthony D. Pellegrini, a recess proponent, in The American Journal of Play summarized the argument like this: Test scores are declining, and so given the limited number of hours in the school day, it makes sense to eliminate or minimize a practice that is trivial at best and, in any case, antithetical to more serious educational enterprise.

According to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 40 percent of school districts reduced or cut recess altogether since the early 2000s.

Guilderland’s superintendent, Marie Wiles, who has worked as an educator for 37 years, said that when “accountability measures” — even judging teachers based on their students’ test scores — became prevalent, “lots of things started to take a back seat to, honestly, reading literacy scores and math scores. A lot of content areas started to get short shrift as well.”

Wiles cited Jonathan Haidt’s best-selling book, “The Anxious Generation: How the Great Rewiring of Childhood Is Causing an Epidemic of Mental Illness.” A social psychologist, Haidt argues that the combined trends of over-protecting children in the real world and under-protecting children in the virtual world have led to the current crisis.

“Not just in schools but in their lives in general,” Wiles said, “[children have] less opportunity and freedom to just play, make up their own games and play with their friends and not have structured activities that begin and end at a certain time with rules and lots of adult supervision.”

Wiles contrasted that with her own childhood where she was free to play outside till the streetlights came on “and no one really was monitoring the games we made up, which were fun and sometimes the tool for problem-solving and how you get along with your neighbors and all of those skills that seem to be lacking and are in need of development these days.”

Currently, only nine states require recess in elementary schools according to the National Association of State Boards of Education: Arizona, Arkansas, Connecticut, Florida, Missouri, New Jersey, Rhode Island, Virginia, and West Virginia with Washington and California deliberating bills.

Even in states with laws that mandate recess minutes — from 20 to 50 — there is no system of accountability for adherence, or even a system that collects data to track how schools implement these policies. Many schools simply don’t comply.

At Guilderland’s five elementary schools, teachers take their students outside to play for 20 to 30 minutes daily “at the teacher’s discretion,” said Wiles, whenever it best fits their schedule, weather permitting.

Several times this past school year, Robert DiPasquale, the parent of a middle schooler, spoke to the school board about the need for recess. His son, who was new to Farnsworth Middle school, DiPasquale said, had “no opportunity to meet his other classmates.”

Farnsworth doesn’t have a playground, Wiles noted, but, she said, “Many teams over the course of the day will take kids outside to one of the courtyard areas.” At the high school, she said, although there is no recess, students “have plenty of opportunities to engage in lots of activities like our interscholastic sports and extracurricular clubs and our music programs.”

Wiles also said, “I don’t feel like the job of the legislature is to define the school day. I think that should be up to local control.”

She noted that Farnsworth Middle School on its own banned cellphones from bell to bell, which “transformed the school day,” making students more engaged with each other and their work while also curbing discipline problems.

Wiles thinks Guilderland would have adopted the ban on its own without the state law “because we know it’s the right thing to do, not because we have to.”

Commitment is starkly different from compliance.

That was the problem with the handed-down regulations on teacher evaluation based on test scores and with the emphasis on tests themselves. Schools were forced to comply without necessarily being invested.

While we support Senator Skoufis’s bill to study recess practices statewide — it will raise awareness about its importance and the lack of equity — we see irony in legislating play.

Not only is it unenforceable as is evident in the states that have adopted such legislation, if it is to work, the school districts implementing play time have to see and embrace its value or the law will be eschewed.

Part of the sea change that is needed is to trust local districts and their teachers with the freedom to educate children as they see fit.

“I am a fan of play,” said Wiles. “I’m a fan of students having fun in their classrooms and finding that learning is fun.”

So are we. And so is UNESCO, the United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization, that specialized agency of the United Nations with the goal of promoting world peace and security through international cooperation in education, arts, sciences, and culture.

UNESCO has a global Happy Schools Initiative, grounded in both science and philosophy, that recognizes happiness as both a means to and a goal of quality learning.

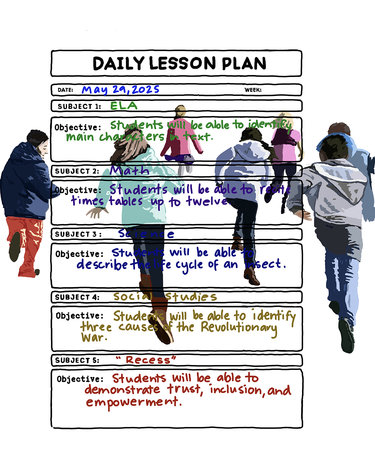

It’s about far more than recess. We believe “recess” itself needs a new name since the word means a break from learning when, as those at the May 20 press conference made crystal clear, play time is an essential part of learning.

The Happy Schools framework rests on four pillars — people, process, place, and principles — and has a dozen criteria for integrating happiness into schools.

The principles are based on trust, inclusion, and empowerment.

If school time is not focused on preparing for a test but rather based on these pillars for happiness, teachers can engage students in discussion and discovery — in playing with ideas that will sustain them for a lifetime.