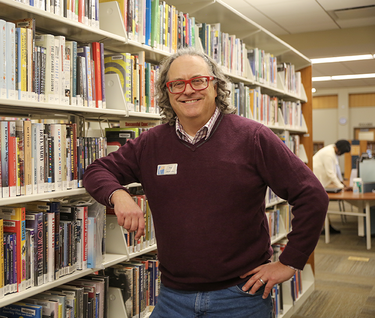

Proud of an expanded and revitalized library, Wiles is passing the baton

GUILDERLAND — “I’ve been sprinting for 10 years,” said Timothy Wiles, who will be retiring on Feb. 2 from directing the Guilderland Public Library.

“In the last year, I tried to jog through this job a little bit, and it’s a complicated, complex job and you can’t jog at it. So it’s time for someone else to sprint.”

A decade ago, when he left a job he loved in charge of research at the Baseball Hall of Fame in Cooperstown, Wiles said he wanted a chance to be a director. This week, he told The Enterprise, “As I hear you reflect my own words back to me, I realize how much I’ve matured in the last 10 years because now I sort of don’t want to be the director.”

He recalled an interview with a famous European actor that he’d recently run across. The actor was asked if he wanted to direct. “He said, ‘Oh, absolutely not. I don’t want to direct. Directing is like being Christopher Columbus. You’ve got to have three ships with all these different experts and you have to keep them all working … I just want to tell a story,’” said Wiles.

Wiles himself, at age 59, has a number of stories he would like to tell.

While directing the Guilderland library he’s continued to do “a steady stream of baseball research and writing for paid clients,” which he plans to do more of.

But he hasn’t had time to write poetry and personal essays.

“I have a series of sort of extraordinary, interesting stories and opportunities that occurred to me while I was working in the world of baseball,” he said.

He gave the example of being “knocked out cold by the Secret Service” during a Baseball Hall of Fame induction ceremony.

President George H.W. Bush had been sitting in the front row at the 2003 ceremony when Wiles performed his rendition, complete with uniform and bat, of “Casey at the Bat.”

Afterwards, Bush came backstage with four Secret Service agents. “He came striding across the 10 or 12 feet between us with his hand outstretched,” Wiles recalled. “And I got up from my chair to shake his hand, and I just happened to be holding my baseball bat …. The next thing I knew, I was waking up flat on my back on the ground.”

What impressed him, Wiles said, “is how incredibly skilled these people are at defending the president.” He expected, after being knocked out, to be sore and out of sorts, he said, “but they’re so good at what they do that it’s like it never happened … I woke up the next day feeling fine.”

Wiles has written “mostly baseball poems” but plans to expand on that. He has signed up for The Stafford Challenge, which starts on Jan. 17 and requires participants to write a poem every day.

“William Stafford is deceased but was one of my teachers in college,” said Wiles. Stafford, who published 65 books of poetry, was known for writing every day.

“Writers write,” said Wiles, adding that he is looking forward to the discipline of writing a poem each day as “a good way to transition from one life to another.”

He plans, too, to do some public-service work as a volunteer and to rejoin the charitable fundraising arm of the library, the foundation of which he was president before he became the library’s director.

“One thing that is in almost everything I write for personal satisfaction is a sense of humor and bemusement,” said Wiles. “I don’t like to think of myself as anything other than just a regular guy that happens to, in the baseball sense, have kind of wandered into some extraordinary experiences.”

He also said, “I’ve also felt that I might have a memoir in my 1970s childhood, which of course was very, very different than the lives that children live today.”

Wiles was taken with Amy Krouse Rosenthal’s “Encyclopedia of an Ordinary Life,” which he came across at the Guilderland library. “She might have an entry on the color blue or lasagna … each of them from her life,” he said.

Wiles grew up in Peoria, Illinois, the son of an accountant father and a piano-playing mother who treasured books. They lived in an early suburb, in a house built in the 1930s at the corner of Stratford and Avalon streets — “two great literary traditions,” he noted earlier.

Wiles recited the vaudeville question: Will it play in Peoria? His hometown, he said, was “a representative cross slice of America — it’s right in the middle.”

“Playing in Peoria” will be the name of his memoir, he said.

“Back then,” he said, “kids did not have a schedule and they didn’t have a chauffeur. What they did between waking up and going to sleep was largely unknown by their parents.”

Wiles got up at 4:30 a.m. to deliver newspapers, which he said few kids do anymore. He recalled the TV had three channels and the telephone was attached to the wall.

He plans to write his story with humor in “contrast to how kids live today.”

Wiles went on, “I have no idea if I will ever reach publication,” but, he said he believes the stigma is gone from print-on-demand services and his memoir “would be something handy for my son and any potential grandchildren to let them know where they came from.”

His son, Ben, is now 16, a junior at Guilderland High School. The family had moved to Guilderland when Marie Wiles, Tim’s wife and Ben’s mother, became Guilderland’s superintendent of schools.

Tim Wiles was commuting an hour-and-a-half each way to his job in Cooperstown and, as Ben was at T-ball age, he said, he wanted to be home more for his son.

“The irony is,” Wiles said this week, “I did not realize at the time that being a library director means going to a lot of evening meetings so I probably could have stayed at the Baseball Hall of Fame and spent just as much time with my son.”

Still, he has no regrets, Wiles said, and turned down a second interview with the Chicago Cubs, his team, which was setting up an archive.

“As a family, you always want to be together,” he said.

Wiles’s last day as the library’s director will be Feb. 2. On that day, his wife will be reading from her recently published book — “Lessons from the Bard: What Shakespeare Can Teach Us about School District Leadership.”

“She looks at five of the most frequently taught plays,” he said, “and finds examples that will be useful to principals, superintendents, board members and teachers in the lessons and language of those plays.”

A decade at GPL

When Timothy Wiles was hired, in January 2014, Christopher Aldrich, who chaired the library’s board, described him as a collaborator who builds consensus, a “people person … passionate about the role of the public library and its mission to educate, entertain, and inform the citizens of the community.”

Aldrich also said, “Tim views problems not as obstacles but as challenges.”

“When I took over in 2014, the staff morale was very low and customer service was really bad,” said Wiles this week. “And the building itself was in awful shape and the board had kind of put all their energy into that 2012 expansion effort, which was, you know, beaten at the ballot box, 3 to 1.”

Wiles went on, “I was brought in to kind of repair the relationship between the library and the community and to work collaboratively … I think I was able to do that.”

One member of the six-person selection committee, Wiles said, thought that since his experience was with a museum library he lacked the skills to run a public library.

“The other five people said to her, ‘Yeah, we know how to run a public library. We need a vision person who can restore our place in the community.’ And so that’s what I tried to do and what I hope people would agree that I did. But now that the renovation is done and the library is, I think, in excellent standing in the Guilderland community, there’s no real vision to implement.”

Wiles concluded, “What they really need now is someone who is familiar with day-to-day library operations … someone who can keep the trains on time — and that’s not my specialty.”

Wiles went over a long list of accomplishments he is proud of during his tenure.

Probably the most prominent is shepherding through an $8.8 million project, which expanded and upgraded the library, in the midst of the pandemic.

The project broke ground in October 2020 and was finished 11 months ahead of schedule and under budget.

The library accomplished this by extending the pandemic closure for longer than some other local libraries, which caused some complaints as the original plan had been to keep the library open during the expansion.

In late 2020, library trustees briefly considered furloughs for some staff but abruptly dropped the notion following a week of tumult in which a handful of protesters holding signs that said “No Furlough” and “Thank You GPL Staff” stood in front of the library on Western Avenue, and a half-dozen letters supporting library staff were published in The Enterprise.

At their December meeting in 2020, the trustees formally offered their “thanks and commendation to the library staff for their work during very difficult times.”

Wiles noted that the library got a new roof and a new loading dock before the renovation and expansion project started.

Wiles recalled when the architect first visited Guilderland’s library, built in 1992, “He said to us, ‘You walk into the lobby of your building and you could be in Rochester or Poughkeepsie or Indianapolis. There’s really nothing here that says Guilderland in any way.’”

Wiles worked to rectify that and noted the “gigantic photo of the Helderberg escarpment that greets you right as you come in the front door,” the original fireplace mantel from the late 18th-Century Fullers Tavern, and the entryway from the now-demolished home built by Altamont’s first doctor before the Civil War.

Wiles also noted the popular cow statue that was donated by the Gruelich family and once stood atop their Guilderland store.

Wiles is still seeking information on — and especially a photograph of — the Westbrook Women’s Club that founded Guilderland’s first library; the library’s newest meeting space is called the Westbrook Room.

An Enterprise account says that women in the club’s library committee “campaigned door to door and received 900 books and a $5 donation for a stamp pad and cards to charge out the books.” The library opened in one room of the Guilderland Elementary School in 1957; for the first six years, the staff was entirely volunteer.

The library moved five times because of insufficient space before having its permanent home constructed in 1992 after it became a public library with elected trustees and the power to levy taxes.

The latest renovation, Wiles said, “dramatically expanded services to children and teens.”

A public survey showed the number-one priority was a café, Wiles said, which opened on Aug. 30.

“We acquired a third parking lot … the whole building is more efficient and safer,” he said. The library has a sprinkler system for the first time and “the cleanest air in town for a building our size.”

The fish tank — Wiles’s idea — is “a very nice, relaxing amenity for both kids and adults,” he said.

The electronic sign out front, next to busy Route 20, he said has promoted programs to the community.

All materials now have chip identification, he said, adding, “This allows us to be a lot more efficient.”

Kids love feeding books into the conveyor-belt system, he said, and adults appreciate the ease and privacy of self-checkout, which between 60 and 70 percent of patrons use.

Wiles said his “absolute favorite comment card in the 10 years that I got here” was in a woman’s florid handwriting. She wrote, “When I’m standing at the counter, checking out books, I really don’t want the clerk to say to me, ‘You have a book that’s overdue called, "Can this Marriage be Saved?"’”

“We brought in $1.3 million in grants during my 10 years that was all used for upgrades and renovations to the building,” said Wiles. “That’s literally more than I made in my tenure.”

Wiles is also proud of the partnerships the library has formed with community groups, ranging from the Guilderland Food Pantry to the Guardian Society.

And, during his tenure, he has been a steadfast proponent for unfettered access to knowledge.

“I feel strongly,” Wiles said this week, “that what makes America great is freedom. And so I just happened to post on my personal Facebook page the other day … a page from the Orlando Sentinel of 673 books that have been removed from teachers’ classroom libraries in that county in the last year … books that kids no longer have access to.”

He recalled that one of just a handful of complaints during his tenure at Guilderland was about a movie the library has.

“I sat down and watched the movie,” he said, “and then discussed it with the person complaining and … managed to show them that there was another way to interpret the movie other than how they were, and that it was actually more of a cautionary tale than a celebration of sexuality.”

Wiles concluded, “We really shouldn’t be talking about one book or one movie or even 673 books or movies. We should be talking about access to books and movies and if we want to live in a country where they restrict that access, there are countries like that, their names are China and Russia and Nazi Germany, and that’s not us.”