Commemorate in a way that fosters repair

Serving as a municipal historian is an important job. Jack McEneny has been nominated by Albany County’s executive and approved by the legislature’s personnel committee to be county historian, a post he held earlier, but a post that has been vacant for years.

We believe McEneny is a good choice. Although he is best known for his work as a legislator — first at the county level and then as a state assemblyman — we believe he is at heart an historian and a teacher.

He co-authored a book on Albany; directed the state’s urban cultural parks program; was instrumental in saving Albany’s oldest building, the Quackenbush House; and initiated an archeological project in Albany. We’ve written about all these things over the years.

But what most stays with us was his work more than three decades ago with a program initiated by Berne-Knox-Westerlo teachers called The Arts Connection. The program paired students from rural Berne Elementary School and Giffen Memorial Elementary School on South Pearl Street in Albany.

“This is a good opportunity for us to all know our neighbors for a change,” said Helen Lounsbury who spearheaded the program and has since retired as an elementary school teacher in Berne.

McEneny, who had taught kids at Hackett in Albany, told us at that time of teaching children about history: “I take the approach that all of us are detectives. The good ones solve the mystery.”

He noted that, at age 3 or 4, kids naturally ask, “Why?” But, he went on, “After a while, in school, they stop asking why. It may be that they’re looking to the teacher for an answer. It may be social pressure … I want to teach them to learn by asking. We have to keep them at it.”

McEneny used what he called “flashback history” to teach the students, taking the known and working into the unknown. For example, he had the students search for houses in Albany’s South End that looked different: They discovered that Cherry Hill and the Schuyler Mansion had been big working farms until “the city gobbled up the farms.”

In the country, McEneny had the students look at the Lutheran Church and the Dutch Reformed Church right across the street from each other in Berne. The “detectives” thereby learned about the waves of immigrants that settled the Hilltowns.

McEneny himself had spent his boyhood summers on Warners Lake as his mother, before him, had summered in a Hilltown boarding house, recalling an era when Native Americans would camp in the woods and sell their baskets.

“We want to show them every community is different and unique, just like they are,” McEneny said at the time.

He had the children, the detectives solving mysteries, work in groups, explaining, “That way, they learn no one person has the answer. A synergy develops in the group. There’s a give and take and, in the end, each member learns more than he would have alone.”

The Albany County Legislature’s Personnel Committee that met in late July to unanimously approve the county executive’s recommendation to appoint McEneny had some give and take.

Legislator Mark Grimm, a committee member who represents part of Guilderland, asked how critical the paid post is if it had been vacant for seven or eight years.

“You just broke the law,” McEneny responded. New York is the only state with a law mandating that a historian be appointed for every municipality.

The state defines four responsibilities for the appointed historians: research and writing in books, magazines, or newspapers; teaching and making public presentations; historic preservation; and organization, advocacy, and tourism promotion.

McEneny spoke of the dignity of the post and the need to bring town and city historians across the county together.

He also gave a history lesson as the 250th anniversary of the American Revolution approaches in 2026 on the importance of the Battle of Saratoga in which Albany County figures like General Philip Schuyler and Thaddeus Kościuszko, the Polish military engineer, played a part. Both of those men did “all the preparation work, the nuts and bolts that had to be done,” McEneny said.

He likened the Battle of Saratoga’s role in the Revolutionary War to the Battle of Gettysburg in the Civil War. “It was the turning point. It made the difference. It gave us hope and eventually brought the country back together,” McEneny said of Gettysburg.

“The Battle of Saratoga,” he said, “had a European, well-trained army, perhaps the best army in the world and, at that point, a somewhat rag-tag civil-for-the-most-part militia got together and defeated a professional military that had been the model of the world,” said McEneny, noting that, after the victory at Saratoga, “We got recognition from the Dutch, from the Spanish, from the French ….”

He said that, if local people — “those that had little to lose but also those that had everything to lose” — had not “put their lives on the line …we would not have had this nation.”

McEneny told the committee that he is distressed to see a trend of people saying “let it go” when it comes to celebrating the 250th anniversary.

This prompted Grimm to ask McEneny what his feelings are on the recent removal of Schuyler’s statue from in front of Albany’s city hall.

“The same thing I told the mayor three years ago,” McEneny responded, referencing Mayor Kathy Sheehan who, in the midst of the Black Lives Matter fervor following the murder of George Floyd, had said the statue would be moved; some city hall workers said it made them uncomfortable to walk by it every day.

“I think it’s a very poor idea,” McEneny went on. “I thought it was not fair to our veterans. It was not fair to our heritage. No one supports slavery, certainly not in this day and age.”

Here is where we sharply disagree with McEneny.

In this day and age, there is a strong racist movement that is openly trying to rewrite or at least recast history. Florida, for example, has decided to teach in its schools that slavery in America was of “personal benefit” to some of the people who were enslaved.

Florida’s newly adopted academic standards for social studies state, “Instruction includes how slaves developed skills which, in some instances, could be applied for their personal benefit.”

Say what?

Africans were stolen from their native lands, chained for horrible journeys across the sea, and forced to work against their will for so-called white “masters.” Any “skills” they may have developed were not used for their personal gain. Rather, their labor enriched their owners and in fact fueled an entire economy from which they gained nothing.

Not only were individuals bought and sold like animals, their children were born into slavery and families had no rights to stay together. The repercussions from these horrors are still playing out today.

A statue glorifies someone — literally puts him on a pedestal.

No sign saying that Schuyler was one of the largest slaveholders in the area would justify the statue’s placement in front of a public hall for a city of citizens that includes many who are descendants of slaves whose labors increased the wealth of the city, the county, the state, and the nation — with no just returns.

Removing the statue from that prominent place in the city is not erasing history. People can still read and learn about Schuyler’s role in the Revolution and his other accomplishments. His mansion stands nearby, as the Berne and Giffen elementary students learned three decades ago; it’s a state historic site and visitors can learn there about all Schuyler did as well as about the people he enslaved.

History is about more than the men who fought in wars. We would urge our new county historian to be inclusive as he goes about his work of exploring and amplifying Albany County’s history.

McEneny needs to take the approach he did with the schoolchildren from the Hilltowns and Albany three decades ago. We need to explore our past like detectives and ask, “Why?”

Guilderland’s newly named town historian, Mary Ellen Johnson, for example, has been doing the copious research needed to uncover scant original documents in hopes of placing an historical marker that documents the contributions of enslaved people to the prosperity of the town.

If we must have monuments, we like the kind that President Joe Biden announced on July 25, which would have been Emmet Till’s 82nd birthday. The Chicago boy was 14 in 1955 when he visited family in the Mississippi Delta where he was accused of flirting with a white store clerk.

Emmett Till’s cousins and friends, who were present at the scene, disputed the claim. Four days later, he was pulled from his bed, kidnapped, and brutally murdered by at least two white men. Three days following his abduction, on Aug. 31, 1955, his mutilated body was pulled from the Tallahatchie River.

His mother, Mamie Till-Mobley, insisted on an open-casket funeral. “Let the world see what I have seen,” she said.

The Emmett Till and Mamie Till-Mobley National Monument will be in three sites: in Chicago, where he had lived; in Mississippi, where his body was pulled from the river; and at Tallahatchie County Second District Courthouse in Sumner, Mississippi where the trial of Emmett Till’s murderers began on Sept. 19, 1955 in a segregated courtroom.

“An all-white jury wrongfully acquitted Emmett Till’s two killers after just over an hour of deliberation,” the White House account states. “Both killers later admitted their crimes to a leading magazine in an interview for which they were paid. No one was ever held legally accountable for Emmett Till’s death.”

We cannot undo past wrongs but, if we acknowledge them and learn from them, perhaps we can avoid repeating them.

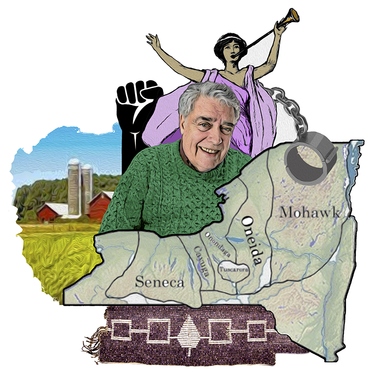

We wrote on this page two years ago of the first comprehensive study of monuments in the United States in which the Monument Lab surveyed 50,000 monuments. The audit names the top 50 individuals recorded in U.S. public monuments. Not surprisingly, the vast majority are white men. The list includes just three women — Joan of Arc, Harriet Tubman, and Sacagawea — and only five Indigenous or Black people.

Our nation’s founding was on stolen Indigenous lands, the audit notes, and much of our country’s foundation was built by enslaved laborers. “Monuments,” the report says, “serve as places to harness public memory and acknowledge collective forgetfulness as twin forces holding up this nation.”

The audit, in which the lab’s research team spent a year scouring almost half-a-million records of historic properties, found that the monument landscape is overwhelmingly white and male, the most common features of American monuments reflect war and conquest, and the story of the United States as told by our current monuments misrepresent our history.

One of the report’s calls to action is to support a profound shift in representation to better acknowledge the complexity and multiplicity of this country’s history. Another is to reimagine commemoration by elevating stories embedded within communities that foster repair and healing.

We have written often about Underground Railroad Education Center — in the reclaimed Albany home of 19th Century abolitionists Stephen and Harriet Myers — and also about the Rapp Road Historic District, a living piece of African-American culture, a neighborhood with homes hand built by Black people who came here during the Great Migration, some with descendants still living there.

Buildings in both of these cases serve as monuments through which we can understand often overlooked or misunderstood parts of United States history.

The current story told by most of our nation’s monuments misrepresents our history. Monuments, the lab report says, play an outsize role in shaping historical narratives and shared memory. “They also can erase, deny, or belittle the historical experience of those who have not had the civic power or privilege to build them,” the report says. “Where inequalities and injustices exist, monuments often perpetuate them.”

The same can be true of celebrations of historical events. As Albany County gears up for the 250th anniversary of our nation’s founding, let us look beyond the well recognized Founding Fathers and war heroes.

Maybe we could focus on the influence of the Iroquois and the cohesion of their confederacy. Or perhaps we could explore the role of local women in the Revolution. Or we could look at the Battle of the Normanskill through an African-American’s eyes as Guilderland’s Aaron Mair has.

A blue and gold roadside marker along Route 146 in Guilderland highlights the Aug. 11, 1777 battle but, says Mair, “What the historic marker doesn’t say and what locals don’t know, is that their ancestors’ freedoms were defended in part by African-American patriots who were part of the 1st Rhode Island Regiment.”

What else don’t we realize? Let’s use that synergy of exploring together that McEneny invoked for city and country schoolchildren three decades ago when he stated, “No one person has the answer.”

“We want to show them every community is different and unique,” McEneny said, “just like they are.”