In wildness is the preservation of the world

We’re writing this in the midst of a heat wave. Many parts of the world on this Thursday, July 21, are hotter than we are here.

In London, the temperature is over 100 degrees Fahrenheit in a city that normally has temperatures in the 70s this time of year. Many homes, like most of London’s subway system, aren’t air-conditioned. The Victorian Hammersmith Bridge had to be wrapped in silver insulation foil so it wouldn’t collapse. Airplanes couldn’t land because of damage heat did to the runways.

Fires raged in Greece and France as well as Spain and Portugal, forcing people from their homes.

This isn’t fair. The European Union has done more to cut greenhouse gasses, developing wind and solar power, than any other developed nations — including the United States.

But that is exactly the problem. It will take the entire world to rein in climate change because the blanket of carbon dioxide emitted on one side of the globe affects places that haven’t contributed to it as much on the other side.

Most unfair of all is that undeveloped places, like the drought-stricken Horn of Africa, produce just a tiny percentage of emissions worldwide yet suffer disproportionately. People are dying.

“People like the elderly, lactating mothers and children, they are dying silently in their homes. They just succumb to hunger,” Jino Bornd Meri, a local government leader in Uganda, told Reuters.

The United States needs to lead on this — our nation is one of the worst offenders — if the world has any hope of succeeding.

We understood the anger in the press release we received from our congressman, Paul Tonko, on July 15, following Senator Joe Manchin’s assertion he wouldn’t support climate and energy provisions as part of the Democrats’ reconciliation package.

This of course followed our Supreme Court’s decision on West Virginia v. EPA that limited the Environmental Protection Agency’s ability to regulate carbon dioxide emissions.

As we’ve written on this page before, legislators need to act when courts don’t follow the will of the people. The executive branch can only do so much as President Joe Biden’s plan to invest $2 billion in the Federal Emergency Management Agency shows. Reacting to a disaster after it happens is too late.

The will of the people is clear.

A 2021 study from Yale shows there is not a single state in our nation where a majority of adults think climate change is not happening. Nationwide, 72 percent believe it is happening.

In Albany County, that number is 78 percent; statewide, it’s 79 percent.

The majority understand that global warming is caused largely by human activity, and that, not only is it affecting the weather, but it is harming plants and animals and will harm future generations.

The Yale study also shows that 72 percent of Americans believe carbon dioxide should be regulated as a pollutant while a strong majority say Congress, local officials, and citizens should do more to address global warming.

“To say I am frustrated by the news last night does not do this feeling justice. I’m furious …,” said Tonko on Manchin’s withdrawal. “Generations to come will inherit a less livable world with a more extreme climate because of today’s inaction.”

But it’s not just Manchin. It is all of our Republican representatives.

How can anyone, in good conscience, watch the word burn and not try to save it?

On July 18, at the start of the United Nations Climate Dialogue in Germany, U.N. Secretary-General António Guterres called for a “renewables revolution” and said, “Nations continue to play the blame game instead of taking responsibility for our collective future.”

He warned, “Greenhouse gas concentrations, sea level rise and ocean heat have broken new records. Half of humanity is in the danger zone from floods, droughts, extreme storms, and wildfires.” Guterres outlined a stark choice: Collective action or collective suicide.

We choose action. If our government won’t help us, we need to help ourselves.

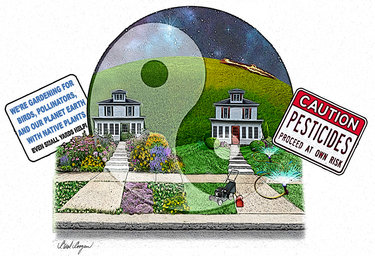

The Yale study pointed to local officials and we call on them now — more ardently than we did on this page a month ago. We urged our town leaders then to do what other towns have done in the United States — support initiatives for native plants to replace manicured lawns.

In Appleton, Wisconsin, for example, which participated in No Mow May, researchers there found “No Mow May homes had three times higher bee richness and five times higher bee abundances than frequently mowed greenspaces.”

Attitudes were changed in Appleton as the tall grasses grew in May 2020. “A post-No Mow May survey revealed that the participants were keen to increase native floral resources in their yards, increase native bee nesting habitat, reduce mowing intensities, and limit herbicide, pesticide, and fertilizer applications to their lawns,” the study said.

A monoculture lawn that is heavily manicured with frequent mowing, and chemically managed is not what is best for the long-term health of our planet. Climate change exacerbates the problems of shrinking biodiversity. It is not the best use of limited water resources, and even letting grass clippings decompose on a lawn can more than make up for the carbon being released.

We heard from Guilderland resident Joan McKeon last week. She plans to organize a workshop to educate neighbors on the worth of native plants. We sent her a list of native plants we published more than 15 years ago, favorites of Laurel Tormey Cole.

“The whole idea of native plants is there is no soil amendment, no additional watering after the first year, no fertilizing, no nada,” Tormey Cole told us back then. A native-plant garden doesn’t even require the usual fall cleanup. “I leave everything up,” she said. “The seed heads will spread their seeds. The wind and snow will topple stuff down.”

Tormey Cole also gave philosophical reasons for liking native plants. She likes growing natives that are endangered or threatened. They fill a niche in a complex ecology humans have yet to fully understand.

And she had another prescient thought: “One of the things that’s going to become an issue in the coming decades is water,” she said. “You put a native plant in the ground for appropriate soil and sun or shade. You water it for its first season … After that, the plant doesn’t need to be watered.”

Sean Mulkerrin has written another story this week on Altamnt’s precarious water situation — the village water supply has plummeted to levels not seen in four decades.

McKeon was inspired to write to us because a neighbor had scrawled an unsigned note, telling her to mow her lawn, saying, “It’s a disgrace to the neighborhood!” McKeon correctly responded that the disgrace is the crime against nature from chemically fertilized lawns.

Her letter reminded us of a book another Enterprise subscriber, Judy Slack, loaned us after reading last month’s editorial: “Nature’s Best Hope: A New Approach to Conservation in Your Yard.”

In “Nature’s Best Hope,” ecologist Douglas W. Tallamy tells of a woman with a naturally landscaped yard so harassed by her neighbors that she leaves. “She had triggered their belief that anything other than a lawn is a low-class product of neglect rather than an artfully designed garden or an attempt to share the land with other living things,” he writes.

Tallamy envisions an upcoming “Age of Ecological Enlightenment,” which he calls the only option left for humans to remain viable. If each American landowner converted half of his or her lawn to productive native plant communities, he posits that ecosystem function would be restored to the current 20 million acres of wasteland — lawns.

We know a society can’t change its sense of aesthetics overnight but local officials can lead the way.

That’s why we were disappointed that the town of New Scotland — a town that has been a beacon of sensible planning to encourage clustering and leave open space — has proposed a law that would make it unlawful to “maintain weeds, grass, or other vegetation to a grow to a height of over 10 inches for over 45 days” or “permit the accumulation of dead weeds, grass, or brush for over 45 days.”

The law has a carve-out to allow No Mow May but misses the larger point that long grasses, native plants (which are often termed weeds) and cut grass left where it falls is healthy for the environment.

New Scotland resident Marsha Carlson has written us a spirited letter this week, pointing out that this year’s Best in Show at the Chelsea Garden Show in the United Kingdom, “looks like hundreds of local gardens in our community, yet according to this law they are slated to be fined and made illegal.”

The winning garden used native British plants in a rewilded landscape, with beavers as its centerpiece, a mammal that has been reintroduced after centuries of being absent from the British landscape.

This reminds us of the importance our yards can play not just for pollinators but for creatures of all kinds.

Today, July 21, the International Union for the Conservation of Nature named the migratory monarch butterfly as endangered. We are all familiar with the beautiful orange and black butterflies that once seemed so common in our yards and gardens.

Year after year, we write about and picture the students at Guilderland’s Farnsworth Middle school who grow the native milkweed in their garden to feed the monarchs and then release them for their annual flight to Mexico.

Let’s take this as a symbol, a call to action to make our yards a haven for the wild things before they disappear.

We know it can be done. It’s worked for other species, other important symbols. The bald eagle, the symbol of our nation, was near extinction before the DDT that thinned its eggs was banned in 1972. We now regularly thrill to the sight of these magnificent birds.

Right in our own backyard, the Karner blue butterfly was on the path to oblivion before a concerted effort of governments, citizens, and scientists reversed its course, giving the butterfly a chance to flourish again along with the native lupin that supports it in the pine bush.

We human beings have such hubris and we understand so little about the natural world we are destroying.

The Karner blue butterfly, for example, has a symbiotic relationship with the black ant. Its cocoon secretes a sweet, sticky substance that the ant covets, and so the ant protects the cocoon from predators, even going so far as to carry a cocoon to its nest for the winter, returning it in the spring.

It’s time for us to realize that human beings, too, can have a symbiotic relationship with nature. There’s a reason parks flourish in cities; we humans crave natural spaces.

But, beyond that, the natural world — and even what we can recreate of the natural world in our own yards — sustains not just us but other species on this planet we share.

This heat wave we’re all enduring, as are others in many places around the world, should make us aware we are part of something larger than ourselves and we are at a moment where we must collectively choose action over suicide.