Besides spreading joy, a pool in the Helderbergs could save lives

Since the pool at John Boyd Thacher State Park was closed in 2006, we have consistently called for a replacement.

We are thrilled this summer to have heard from Enterprise readers making a similar call.

Timothy J. Albright of Meadowdale, who has known and cared about the park since he was a boy, wrote a long letter on Aug. 4, “We citizens got nothing to replace our pool at Thacher; it’s needed as climate warms.”

He named the many state parks with pools and cited the population of over 1 million for the Capital Region. “Let’s agree,” wrote Albright, “Thacher Park is the closest, most significantly recognized state park to the New York State capital city of Albany and is only about 12 miles from the city. Thacher Park has easy access from the city and is revered by many as a remarkably special place.”

He notes, “The Helderbergs and Thacher Park have always been the cooling retreat from the urban areas of the Mohawk and Hudson valleys because of the elevated topography.” This includes the Thachers themselves — Albany Mayor John Boyd and his wife Emma Treadwell Thacher, who donated their Helderberg land to the state after her husband’s death.

Albright argued, “With summers getting hotter and Thacher Park having historically had a pool, it’s an appropriate attraction and not a detraction. Admission fees will offset maintenance costs. Snack bars properly run and managed can profit.”

During this summer’s heat wave — July was the Earth’s hottest month ever — we reported on state swimming venues, like the campground at Thompsons Lake, now a part of Thacher Park, being kept open for longer hours. People living in homes without air-conditioners or working outdoor jobs needed relief.

Of course, we continue to maintain that the underlying cause of climate change has to be our top priority — our use of fossil fuels has to be curbed. And the federal government has now given us the incentive, with generous tax breaks, to do that by switching our home heating systems and the vehicles we drive to those that are less harmful.

The heart of Albright’s letter is that he feels betrayed by our state government. We don’t disagree.

The Olympic-size pool, which had served for more than half a century, was leaking, and the public was promised it would be replaced with a complex including a new bathhouse, a 7,000-square-foot “leisure pool,” a free-swim area, a large and looping waterslide, and a 3,000-square-foot spray pad with shallow water in the shell of the old pool. Half of the cost was to be covered by a grant from the Federal Land and Water Conservation fund.

We wrote on this page in 2007, in an editorial called “We’ll sink or swim together,” that the pool had been closed for two seasons with no plans for replacement.

“This is a shame,” we wrote then. We reiterated our coverage of the fanfare when the state’s Office of Parks, Recreation and Historic Preservation announced that Thacher would be the first state park in New York to get a waterslide, part of a $3 million project to renovate the pool complex.

That was under Governor George Pataki’s administration. When we checked back on why no new complex was forthcoming. The new spokeswoman, after Eliot Spitzer had been elected governor, told us, “When the new administration took over and looked at the needs of various parks,” the initial plan didn't look feasible.

A state park pool shouldn’t be a political football. It fills an important need not just for the rural area where it is located, which has no other public pool, but also for the larger Capital Region.

We tried again on this page to make the case for a pool at Thacher Park a decade ago, in 2013, when the park was developing its first master plan. While we praised much of the plan, we criticized the proposal to use the former pool site for a “challenge course” with ropes, cables, and obstacles.

The course, which would “invite participants to confront their fears in a controlled situation,” would be operated by “park personnel who will receive training from professional challenge course instructors,” the plan said.

We asked then: If the point of the “challenge course” was to draw visitors, why not rebuild the pool, which was a centerpiece of the park for decades?

We argued then that it would be more worthwhile to train park staff to teach swimming — although Red Cross-trained volunteers used to do a good job for no pay — than it would be to train them to run a challenge course.

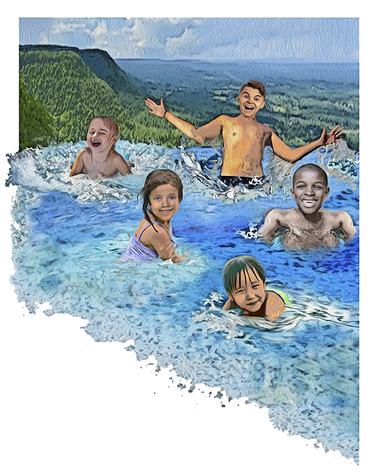

We didn’t care, and still don’t, about a waterslide or a $3 million playland. What is needed is a safe and available place for children and grownups to gather, to learn how to swim and to enjoy each other’s company in the beauty of the Helderbergs.

The pool was part of an economic engine in the Helderbergs. Generations of Hilltown residents worked at the Thacher pool — as ticket-takers, in the concession stand, in the locker rooms, or as lifeguards. The attraction drew thousands to the park, spilling over to help fuel the local economy.

The old pool also fulfilled a, perhaps unintentional, social function. It was one of the few places in the rural Hilltowns where children of different backgrounds — rich and poor; black and white; bused in from the city, driven in from the country — swam and played together.

This week, we’re publishing a letter from a former Guilderland resident who was inspired by Albright’s letter to share a crystal-clear memory from her childhood.

Vicki Meade writes compellingly of the day, when she was 6 years old, that her father held her in the Thacher Park pool. “Dad’s arms hold me tight and I notice how light I feel, how the bright sun and cloudless sky add to my sense of buoyancy,” she writes.

Meade urges, “It would be nice if, in the future, another little girl could go there with her family, play in the big blue pool with her dad, and hold onto a shiny memory that lasts a lifetime.”

Meade’s letter led me to plumb my own memories. Like Meade’s father, I once held a child, a Fresh Air summer visitor, in my arms in the Thacher Park pool.

She had never been in a pool before. Her body was stiff against my own and I could feel the shivers running through her but, over time, as I stood holding her in the warm sun, I felt her relax and, as she leaned back to look at me, a smile spread over her face.

But, unlike Meade’s crystalline moment, most of my Thacher pool memories are a blur, spanning generations. I went to the pool as a child with my mother and sisters many, many times; as a teenager, I taught children to swim in the pool’s cold waters; as an adult, I brought my own children to the pool.

All of this made me realize its importance, beyond the sentimental memories, beyond the good times and meaningful relationships, even beyond the economic boost the pool gave the region.

Teaching people to swim can be a matter of life and death.

The statistics are sobering. According to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, more children ages 1 to 4 die from drowning than any other cause of death. For children ages 5 to 14, drowning is the second leading cause of unintentional injury death after motor vehicle crashes.

Across the United States, the CDC reports, there are an average of 11 drowning deaths per day. In addition to the 4,000 fatal drownings daily, there are another 8,000 nonfatal drownings — for an average of 22 each day.

For every child under age 18 who dies from drowning, another seven receive emergency-department care for nonfatal drowning, the CDC reports. Nearly 40 percent of drownings treated in emergency rooms require hospitalization or transfer for further care compared with 10 percent for all unintentional injuries.

The drowning injuries that don’t kill can cause severe brain damage that may result in long-term disabilities such as memory problems, learning disabilities, and permanent loss of basic function — a vegetative state.

These risks are real and present every time a kid is tempted on a hot summer day to jump into an untended swimming pool or pond or river or swimming hole.

Maybe it’s because we had to report on another drowning this week but we state with urgency once more: Having a pool where people can safely learn to swim would be a wise investment for the state.

— Melissa Hale-Spencer, editor

I wish we could put some pressure on our politicians to get the pool back. On different forums, I read comments by New Scotland residents who would love to cool down in a pool or bring kids. Or even learn to swim...Tawasentha is not for outsiders, The Elm pool in Delmar is strictly for residents of Delmar, and the Bozenkill is for Altamonters only. That is how I understand it. That leaves us with nothing...Sad.