Latest hiccup for Voorheesville Quiet Zone: $50K in annual maintenance

— From the California High-Speed Rail Authority

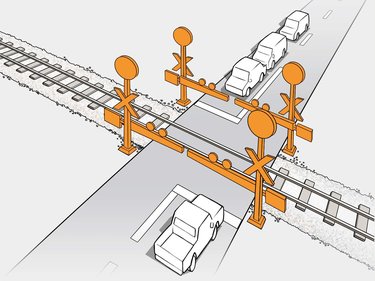

Installing four-quadrant gate systems at Main Street and Voorheesville Avenue would allow engineers to not have to blow their whistles as they travel past the two crossings because the quad gates are designed to block all lanes of traffic on both sides of the track. CSX says annual maintenance of the gate systems would be $50,000 and is looking for Voorheesville and Albany County to foot the bill.

VOORHEESVILLE — Voorheesville’s decade-long quest for a Quiet Zone — so train horns don’t sound in the village — has hit another snag.

It was just a year ago that CSX and Norfolk Southern were tripping over one another, as they planned to route mile-long, double-deck trains through Altamont and Voorheesville, to pick up both villages’ tab on the expensive rehabilitation costs associated with the deal the two freight carriers struck as part of CSX’s $601 million acquisition of Pan Am Railways.

But now, nearly 12 months after it rescinded its objection to the deal, Voorheesville finds itself in roughly the same position it did in December 2021, with the Quiet Zone project appearing to be back on track, only now Voorheesville could be looking at $50,000 in annual maintenance costs for the two safety gates it has been seeking for a decade.

The way the railroad crossings on Main Street and Voorheesville Avenue are currently configured, the 35 trains rolling through the village each day — with some taking as long as 18.5 minutes to do so — according to the most recent Federal Railroad Administration data, from December 2020, have to blow their whistles as they pass through.

Installing four-quadrant gate systems at Main Street and Voorheesville Avenue would allow engineers to not have to blow their whistles as they travel past the two crossings because the quad gates are designed to block all lanes of traffic on both sides of the track.

But it’s not all doom and gloom.

“It does feel like at this point things are breaking loose,” Voorheesville Mayor Rich Straut told the trustees at their Nov. 22 meeting.

There are meetings being had. Contracts are being rebid. The sides agree on most things. It’s just that the $50,000 request for maintenance came out of nowhere, Straut said.

History

In November 2020, CSX reached an agreement to acquire Pan Am Railways and its subsidiaries and their 1,200 miles of collective track. Norfolk Southern owns a 50-percent stake in one of the seven subsidiaries, Pan Am Southern.

As part of the deal, CSX agreed to let Norfolk Southern bring back into service its currently unused tracks along Prospect Street and merge them with CSX’s rails that pass over Main Street to run two trains a day between Massachusetts and points west of Voorheesville.

The village raised its objection to the Surface Transportation Board and laid out a number of concerns it had and then entered into discussions with CSX and Norfolk Southern.

“A big part of that has been the fact that it was disrupting the efforts that have been ongoing for about a decade to establish a Quiet Zone,” Straut said in December 2021, as he announced all sides had come to an agreement in the matter.

Throughout the process of getting the project underway, there have been questions about funding it and who owns it. The gates would sit on county land. And, since the beginning of the process, Albany County has been the lead applicant when applying for state money.

But the type of money the county received, from the state Dormitory Authority, requires it to be used on an asset, two four-quadrant gate systems, that Albany County would have to have some type of ownership of or an extended lease interest in.

CSX typically owns the gates and charges the municipality to install and maintain the system. Here, Albany County and Voorheesville lucked out on two fronts: Norfolk Southern and CSX agreed to pay for nearly everything related to the crossings at Main Street and Voorheesville Avenue, while the ownership issue, about which Straut said in September 2021 that CSX “seemed agreeable” with the county owning the gates and the freight carrier maintaining them, appeared to be settled when the question was raised again by resident Steve Schreiber at the Nov. 22 board of trustees meeting.

Two agreements

There are two agreements for the Quiet Zone: one largely settled for construction and one that nobody saw coming for maintenance. There is still no signed agreement between the county and CSX, but the mayor said he expects something to come together in the next several weeks.

Straut sounded optimistic, telling Schreiber the contract for engineering services would also be rebid.

The county legislature in March 2021 awarded Saratoga Railroad Engineering a $131,440 contract for design and inspection services, but that was put on hold with CSX’s attempt to takeover Pan Am.

“They feel that enough time has gone by that they need to re-solicit the engineering for the county’s portion of the design,” Straut said.

When the village agreed to withdraw its complaint with the Surface Transportation Board last year, in return it received separate commitments from each company: CSX would continue to cooperate and assist in the ongoing design work, while separately the carriers both agreed “to advance the survey and design work for the Quiet Zone project.”

Then in “one of the most significant aspects” of the agreement, as Straut put it in April, CSX said it would keep construction costs to its August 2016 estimate of approximately $288,000. Norfolk Southern, in addition to agreeing to absorb up to $125,000 of additional Quiet Zone-related costs, is incurring all costs related to construction of its Main Street crossing and CSX connection.

The county received $340,000 to pay for the project in 2018.

Currently, “it seems to be” that “the biggest stumbling block now in connection” with the agreements “is the cost of the maintenance,” said village attorney Rich Reilly.

When asked by Schreiber who would foot that cost, the village or the county, Straut said what’s been discussed is shared responsibility. “But we haven’t gotten into specifics yet.” Straut said he has a call next week with CSX to discuss the costs. “I’ve expressed my concerns about maintenance costs three times to CSX,” he said.

With Norfolk Southern and CSX willing to shoulder what could end up being expensive construction costs, the question of who would pay for upkeep came as a surprise. “That came out of left field because there was no mention of maintenance” in the December 2021 agreement between the village and freight carriers, Straut said, because “I would have thought that would have been kind of laid out at that time.”

The maintenance figure is somewhere in the neighborhood of $50,000 per year, Straut said during the Nov. 22 meeting. The Enterprise reached out to CSX for an explanation of the maintenance costs, and received the following statement in response: “As discussions are ongoing with the village of Voorheesville, we cannot provide comment on project cost estimates at this time.”

Comparable costs?

Two of CSX’s peers offer estimated maintenance costs far below that of the Florida-based freight carrier. Union Pacific on its own website puts its annual maintenance between $4,000 and $10,000. While archived versions of Norfolk Southern’s site show the same cost for maintenance of a quad gate.

The city of Plymouth, Michigan in June 2015, ultimately had to abandon its attempt to install multiple Quiet Zones across the city, but not before the municipality examined the cost of maintaining seven of CSX railroad crossings at an estimated cost of $50,000 per year, or about $7,150 per crossing per year.

The Michigan study was based on the experience of a Texas municipality that chose a lower-cost two-gate option for its nine installations, which had $50,000 in annual maintenance costs.

More recently, in May 2021, the city of Monroe, Washington, estimated its annual cost for a four-quadrant gate maintained by BNSF, the country’s largest freight-carrier by bank account, would be between $15,000 to $25,000 annually.