Not everything flying over schools needs regulation

Leaders of the schools we cover frequently say their top priority is safety.

This is admirable. Students cannot learn and teachers cannot teach in an environment where they feel threatened. The quest for safety touches all aspects of school life — from properly inspected school buses to educating students on the harm of racist or sexist slurs.

And, of course, hovering over all schools these days is the worry about school shootings. Although school shootings loom large in the popular psyche, the annual percentage of youth homicides documented as occurring at school is generally around 1 percent of the total number of youth homicides.

The solution to both the 99 percent of youth killed at home or on the streets and the 1 percent killed at school is the same: gun control. Other nations don’t allow such slaughter of their youth.

So we were empathetic when we learned from Senator Neil Breslin’s chief of staff that the Bethlehem Central School District has requested a law to prevent drones from flying over schools. Like everyone else, we want to keep our youth safe.

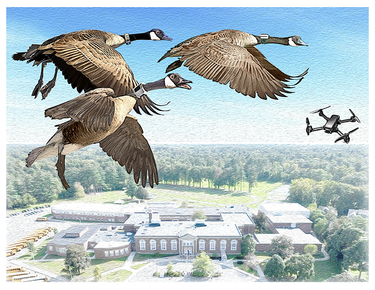

We had printed a short story in our Oct. 19 edition, “FAA: Drones allowed to fly over schools,” about a drone, on Oct. 12, flying over several public schools in town — Slingerlands Elementary, Eagle Elementary, and the Bethlehem Central High School — causing reports to the police.

Bethlehem officers responded and located the pilot who provided his Federal Aviation Administration credentials and explained he works for CoStar Group, a commercial real estate company.

According to the FAA, the Bethlehem Police said, the drone pilot has the legal authority to fly the drone over schools as they are not designated “no fly zones.”

Bethlehem Police asked the CoStar Group to notify them and the school district “regarding future activities that require them to fly over school grounds.”

That seemed to us like a wise response on the part of the police, handling any worries that might arise at the schools while still allowing the FAA to keep airspace navigable.

Then a press conference was held with the county sheriff, and local police and politicians as Assemblywoman Patricia Fahy touted the proposed legislation.

“Drones are innovative tools, but state regulation of them is virtually nonexistent,” says Fahy on her Facebook page. “This legislation will provide parents, teachers, and school administrators peace of mind while protecting our students’ privacy and safety.”

Drones are, indeed, innovative tools. They were developed by the United States and Britain during World War I, known as unmanned aerial vehicles or UAVs. The name “drone” started being used in the 1930s after a British model was named the DH.82B Queen Bee. UAVs were used by the military for training and target practice until the Vietnam War when they were widely used for reconnaissance.

But their rapidly-growing uses far exceed military deployment. Aside from the aerial photography the real-estate company was doing — and which The Altamont Enterprise also does as do many news organizations — drones are used by first responders on search-and-rescue missions, are used to send aid to hard-to-reach places during disasters, and are used to help control forest fires.

Drones have revolutionized agriculture, safely surveyed mining structures, helped with conservation efforts, monitored construction projects in real time — the list goes on.

It makes sense to have one nationwide agency — the Federal Aviation Administration — oversee the piloting of drones just as it oversees the piloting of planes. To have a patchwork of regulations — state by state or city by city — would make airspace difficult to navigate.

Enterprise reporter Noah Zweifel, in a front-page story last week, looked into the efficacy of the newly proposed bill.

The FAA, in a statement to The Enterprise, suggested that this law would overstep into the administration’s jurisdiction.

“The FAA is responsible for the safety of our National Airspace System. This includes all airspace from the ground up,” the statement read (emphasis theirs). “While local laws or ordinances may restrict where drones can take off or land, they cannot restrict a drone from flying in airspace permitted by the FAA. We prohibit drones from flying over designated national security sensitive facilities like military bases, national landmarks and certain critical infrastructure such as nuclear power plants.”

Breslin’s chief of staff told Zweifel that changes would be made to the bill before the January legislative session while Fahy’s chief of staff said the assemblywoman stood by the bill as proposed, referring to a document published by the FAA that says some exceptions will be made for “privacy-related” restrictions over schools, parks, and other areas considered sensitive — though it does not say outright that these laws are permitted in all cases.

Instead, the FAA document says that any such law “would more likely be permissible because of its lesser impact,” relative to, say, a town- or city-wide ban.

“For example,” the document reads, “a privacy-related ban on [Unmanned Aerial Systems] operations over an entire city would very likely be preempted because it would completely prohibit UAS from using or traversing the airspace above the city and impede the FAA’s and Congress’s ability to safely and effectively integrate UAS into the national airspace.”

Elsewhere, the document says, “Restrictions on how UAS are utilized (i.e., conduct) instead of where they may operate in the airspace would more likely be consistent with Federal preemption principles.”

When reached for clarification and questions about the pre-emption process, which is how the FAA overrides conflicting local laws, an FAA spokesperson referred to the same document.

Fahy’s spokesman said, “We are discussing exactly this with the FAA.”

It is not clear to us how this law, if passed, would make schools safer nor how it would be enforced.

“Like you, we are also not entirely familiar with what drones can do,” Bethlehem Superintendent Jody Monroe told The Enterprise. “That is why they pose an unknown threat and why it makes sense that there should be some rules regarding their use around schools …. At the same time, we are responsible for protecting student privacy. The use of drones and aerial photography without authorization is an invasion of that privacy.”

Most schools these days have cameras filming students and staff, even on school buses. If the worry is that drone photography could be used to case a school for a shooting, we would note that cell-phone cameras are so ubiquitous that anyone inside or outside a school could film without being noticed.

Monroe concluded, “The fact that there are no laws to help prevent this counters everything we strive to do in the name of safety. If signed into law, a measure like this one could offer a level of protection for schools that does not currently exist.”

One of the posts on Fahy’s Facebook page touting the bill asks, “Why is this an issue.” Thomas Gammel asks, if it is an issue, “why can they be allowed to be used over my home or place of business.”

We’ve heard accounts of people being bothered, and even frightened, when commercial airliners were new and flew overhead. Others, though, flocked to the outside of airports with their lawn chairs to watch for hours the modern miracle of human flight.

One man’s nuisance is another’s thrill.

Drones are here to stay and their uses are becoming more prevalent.

Asked about concerns with drones, Bethlehem Deputy Police Chief James Rexford had some honest answers. One known concern, he said, is that drones can provide a live feed of activity at a site, which makes it potentially more useful for surveillance than a program like Google Earth, which allows people to look at static satellite imagery of virtually any place in the world, including schools.

When asked how the law would be enforced, Rexford said his understanding is that “new drone devices must have a device on them that allows them to be tracked.”

Although he said he was “not that familiar with this technology,” he assumed the tracking mechanism would be used for identifying the drone and operator. “I cannot answer how this device would be useful if the drone is already gone prior to the arrival of law enforcement,” the deputy chief concluded.

We believe our local police have their hands full without having to chase down drone pilots flying over schools. Our youth need support in many ways — this one seems to us a distraction from more important needs.

If the bill were to become law it would, of course, apply across the state, affecting rural areas where drones are used to survey forests and dust crops as well as cities where we believe police can better spend their efforts preventing gun violence.

Remember, 99 percent of youth homicides occur outside of schools. The public’s limited resources for police service and protection would be better spent elsewhere.