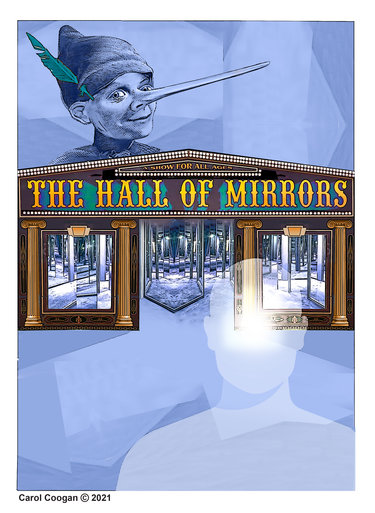

Searching for the truth in the Hall of Mirrors

Our governor did not mince words last week. She didn’t say that “misinformation” was standing in the way of some people getting vaccinated against COVID-19.

Kathy Hochul said one of the identified reasons people aren’t getting vaccinated “is that they are believing the lies on social media.”

Lies.

She went on, “It’s dangerous, it’s misleading, and it puts people at risk and it’s hindering our entire battle against COVID because people are reading this.”

We’re in the business of truth-seeking. It’s not an easy business.

The pandemic has laid bare many problems in our society. One of them is the problem of how most of us get information.

With the coronavirus, having the right information can be a matter of life and death.

It’s difficult because the scientific understanding of a new disease is ever-evolving so the public-health recommendations are changing, too.

It’s hard to keep up with the emerging research, much of it released before it is peer-reviewed.

Every week, we hear at The Enterprise from people who are confused or angry or upset about what they’ve heard or read.

So we applaud the state for launching a campaign, #GetTheVaxFacts, last week to set the record straight on some of the most frequently misunderstood aspects of COVID0-19 or its prevention and treatment.

On its website, the state urges each of us take four steps to stop the spread of misinformation:

— Verify before sharing; don’t share something on social media, until you’ve checked if the original source of the information is trustworthy;

— Be cautious when it comes to sensational headlines and images;

— Get the full story; misinformation often “cherry-picks” or elevates a small piece of a story in order to mislead or alarm you; and

— Amplify trustworthy sources in your community; help to spread good information by sharing what is accurate.

These are worthwhile steps to take on any subject.

The site then goes on to explain and, citing reliable sources, debunk some of the most common “myths” circulating about COVID-19: that the vaccine can cause infertility or that its development was dangerously rushed.

We’ve heard these very falsehoods as we go about our work of trying to fairly cover local news.

Someone in an angry crowd at a Guilderland School Board meeting shouted at a teacher using the word “vaccination” that she shouldn’t call it that; she should call it “experimentation” instead.

Someone on a local anti-mask Facebook page posted advice to others on how she got her daughter out of her college vaccination requirement because it would affect reproduction.

On Sept. 29, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention issued a dire health warning urging pregnant people to get vaccinated – sharing the startling news that 97% of pregnant people hospitalized due to COVID-19 were unvaccinated, the #GetTheVaxFacts site reports. Sadly, outcomes including preterm birth, neonatal events, and stillbirths have been reported among unvaccinated pregnant people who contracted COVID-19.

It may seem that COVID-19 vaccines were developed with unusual speed, the site says, but in fact, there are years and even decades of research that went into developing the vaccines and no steps were skipped in clinical trials that all other vaccines or drugs seeking FDA authorization must go through. The site goes on to detail those steps.

Earlier this year, Vivek H. Murthy, the United States surgeon general, put out an advisory on confronting health misinformation. In it, he said the unprecedented spread of information — including both news and health guidance as well as rumors, myths, and falsehoods — have been called an “infodemic” by the World Health Organization and the United Nations.

He makes a distinction between “misinformation” often spread unintentionally, and “disinformation,” which is spread intentionally to serve a malicious purpose.

Murthy notes that health misinformation is not new; it has reduced the willingness of people to seek effective treatment for cancer and heart disease among other conditions. But, in recent years, he says,misinformation has spread at unprecedented speed and scale.

Misinformation spreads quickly on social media platforms because it is often framed in a sensational and emotional way, because engagement rather than accuracy is rewarded on these platforms, and because algorithms that determine what users see often reinforce a misunderstanding through repetitions.

“More broadly,” Murthy writes, “misinformation tends to flourish in environments of significant societal division, animosity, and distrust.”

So here we are — in just such a place. What do we do about it?

Murthy outlines action plans for various parts of our society.

For schools, he advocates strengthening evidence-based programs that build resilience to misinformation and to set up metrics to assess progress in information literacy as students are taught how to find truth.

Murthy urges health professionals to engage with their patients to understand their beliefs and values, to listen with empathy, and to correct misinformation.

Journalists are advised to recognize and correct misinformation as well as to proactively address the public’s questions, to provide context, to use a broad range of credible sources, and to be careful that headlines and pictures inform rather than provoke.

Technology platforms are told to strengthen the monitoring of misinformation, to evaluate internal policies and be transparent with the findings, and to protect health professionals and journalists from online harassment.

Government is asked to modernize public health communications, and to promote educational programs that help people distinguish evidence-based information from opinion and personal stories.

The list goes on. We’ve included this much — although we advise each reader to review the entire document with its 62 footnotes — to see what role you can best play, what need you can best fill.

We, as journalists, find Murthy’s action plan relevant to what we do, not just in our coverage of the pandemic, but in our coverage of all local news.

And, for us, that is the value of his advisory. It is rooted, of course, with what has been amiss in dealing with the pandemic. But, really, the flow of accurate information is critical for the good health of any society, particularly a democracy.

Murthy writes in an opening statement, “Limiting the spread of health misinformation is a moral and civic imperative that will require a whole-of-society effort.”

That means each one of us must participate. And if you are not part of one of the groups for which Murthy has outlined an action plan, take heart: You still have an important role to play.

For our society, our democracy, rests on the shoulders of each individual. “Before posting or sharing an item on social media ...,” writes Murthy, by way of example, “we can take a moment to verify whether the information is accurate and whether the original source is trustworthy.”

Murthy also advises, “When talking to friends and family who have misperceptions, we can ask questions to understand their concerns, listen with empathy, and offer guidance on finding sources of accurate information.”

These are simple steps that can become worthwhile habits if we make use of them, much like the guidance offered in the state’s campaign.

We at The Enterprise don’t want to have to report the COVID-19 death of another unvaccinated Albany County resident. It hurts our heart and weighs on our soul.

We, each one of us, need to work together on this. And we need to start now.