The common good starts with respect for individuals

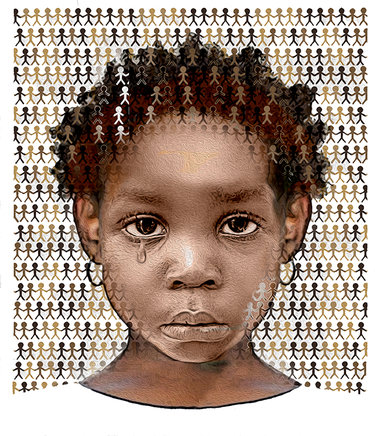

Guilderland is not unique. Racism is everywhere in our society. That doesn’t mean it should be tolerated. Each of us should work, as the Guilderland schools are, to combat racism. You have to recognize a problem in order to solve it.

On Friday, Oct. 14, at a football game — Guilderland was playing Christian Brothers Academy in Colonie — the Red Sea was in the bleachers it is for every game. Named after the school color, the Red Sea is a cheering section for any student who wants to join.

We remember a foreign-exchange student talking about the joy of being immersed in an American experience by shouting for the school team as part of the Red Sea. Supporting fellow students on the field, being part of something larger than yourself can be wonderful.

But, at that game, wonder was replaced with something else: hate or cruelty or lack of awareness, depending on who you talk to.

The Red Sea has different dress themes for the games. On Oct. 15, the theme was “black out” and everyone was, according to the school principal’s account, asked to dress in completely black clothes. Some students painted their faces black.

While students painting their faces white for an earlier “white out” theme would have caused no concern, this is different. Blackface has a long and ugly history in the United States. White people spread racial stereotypes in the 19th and early 20th centuries as they painted their faces black to perform as “darkies” in minstrel shows.

On Saturday, the school principal, Michael Piscitelli, emailed a letter to parents, also posted to the district’s website, saying that administrators on duty at the game asked the students in blackface to leave the bleachers, addressed them about their actions, and directed them to wash off the face paint in the bathrooms.

“Although the students may have done this as part of the theme,” Piscitelli wrote, “we understand how upsetting it was to see students dressed up in this manner and Guilderland does not tolerate any type of discriminatory behavior.”

After receiving the principal’s email, one parent wrote to The Enterprise, “I am tired of the racism at this school district. For years my child has endured countless acts of varying degrees of racism.”

On Monday, Oct. 17, about 100 Guilderland students staged a walkout. In an email to GCSD Families, also posted to the district’s website, Superintendent Marie Wiles and Matthew Pinchinat, the district’s director of diversity, equity and inclusion, wrote that the incident at the football game was a “culminating moment for students, prompting the need for them to discuss discriminatory issues and injustices.”

The letter went on to say the district will not tolerate racism and that it celebrates the diversity that defines it. On the day of the walkout, Wiles and Pinchinat said, “Students expressed to district and building administrators the hurt, anger and frustration they feel due to the injustices they have experienced.”

Guilderland is now on the right path. It is acknowledging racism and working to combat it. This wasn’t always true.

Racism no doubt exists in schools across the United States because it is prevalent in our society. What matters, what can make a difference in students’ lives, is a school’s response.

Over the decades, The Enterprise has covered a number of racial incidents at Guilderland in which students and their parents felt the district was not responsive — several came to public notice only when lawsuits were filed.

One case centered on teacher John Birchler, in the midst of a discussion on the harm of name-calling, asking the only Black student in his classroom, Elizabeth Graham, “Liz, why not tell us what it feels like to be called a n---er?”

“We can all feel relieved,” said the teacher when the suit was dismissed and such discussions could continue.

Later, as a college student, Graham wrote a letter to the Enterprise editor saying of Birchler, “It was like having a bleeding gun wound. He shot the gun and hit me. Yet he found it amazing that I was bleeding. He was sorry that I was hurt yet found nothing wrong with shooting the gun at me.”

At age 20, she wrote that, at 16, living in an “all-white community,” she had never been called a n---er. “If he made this association so quickly, did the rest of my teachers? Did the rest of my friends? And what about my peers, coaches, neighbors? They were all white. In a town that I had felt so secure in, I suddenly felt isolated and alone solely because I am Black, an irreversible characteristic,” Graham wrote.

She also wrote, “Though now, with a much stronger sense of self, I am still in the process of that healing. I ask that my community would first recognize the problem and then to mentally and spiritually join me in the healing process. Few things are done overnight. Purging racism from one’s mind is not one of them….”

A decade later, in 2006, the Guilderland school district again felt relief when this time a federal judge dismissed a suit claiming racial discrimination.

The suit, brought by Garrett Barmore, stemmed from a 2003 incident in which two African-American students got into a fight in the school cafeteria with a white student who called them “n---er.”

The two African-American students — Barmore, who was 17 at the time, and his friend Andrew Dillon, who was 18 — were both charged with disorderly conduct, a violation, and third-degree assault, a misdemeanor. The white student, Jordan Peceri, was not charged in the incident.

Barmore’s lawyer, Paul Wein, said that, after the arrest, Barmore received death threats on his home computer; using the screen name “Death to Darkies,” the sender’s messages included white supremacist rhetoric.

“There’s a totality of circumstance … the failure to address racism at the school,” said Wein at the time. “School administrators did not do their job and they tried to make the victims pay the price for their own failure.”

The judge assessed $9,500 in court costs against Barmore, to be awarded to the district. Peggy Barmore, Garrett’s mother, told The Enterprise at the time that the district offered to reduce that amount if her son signed an agreement, stating he would not talk to the press; he did not sign.

He talked to us and we wrote his story. We thought it might bring about change.

What did bring about change in Guilderland was the nationwide racial reckoning that followed the murder of George Floyd. Wiles and other school leaders listened to a half-dozen Guilderland graduates, all of them Black women, talk about the racism they had experienced while students in the district.

“If we do not seize this moment to make real changes, shame on all of us …,” Wiles told us in the summer of 2020. “We’re at a watershed moment in our country. George Floyd and what happened to him just woke people up. Great numbers are starting to see there really is systemic racism that we haven’t been really appreciative of.”

She also said, “This is more than just about Guilderland Central School District .… The conversation has to extend to our larger community. I welcome everyone to be courageous and dive in ….”

School board members were passionate about pursuing changes in curriculum, policy, and staff training and recruitment. The board created a new administrative post, DEI director, and filled it with a popular teacher, Pinchinat, and appointed a DEI committee.

In 2021, after two racist incidents — racist words were written on a library book at the high school and written passes were circulating among middle school students, giving the holder of the pass permission to say the N-word — Pinchinat started an initiative called “DEI: A Space for You,” where students could fill out forms to get support.

The DEI committee met on Wednesday, Oct. 19, and discussed the blackface incident and resulting walkout. With social media “sparking” what happened at the football game, Pinchinat said, the rally that followed centered on stories — stories of students’ pain, stories of students being marginalized.

Pinchinat, who is Black, said it was impossible to listen to the stories and not be moved. He stressed that the struggles are not new and go back to experiences students had in elementary school.

“How do we move forward as a community and how do we move forward as a district?” asked Pinchinat.

Wiles said smaller forums will be set up so students can share their experiences.

“This is really an example of how adults can fail students,” said Seema Rivera, a committee member who is also the school board president. She said some people “might live in a bubble” and concluded, “I personally believe this was setting up students for failure.”

Rivera told The Enterprise later that adults should not assume students are “aware of what is OK” but rather should teach them, for example, about why blackface is offensive. People have a right to be mad at the school district, Rivera said, but she gave the school credit for addressing the issue.

Rivera, who graduated from Guilderland in 1997, said she “definitely saw some racism as a student.” She noted that students now are more socially aware and “given more voice” — and also that the district is now more diverse.

According to the State Education Department, the Guilderland school district has 190 African-American students, or 4 percent; 181 Hispanic students, also 4 percent; 647 Asian students, or 13 percent; 3 Native American students, or 0 percent; 169 multi-racial students, or 4 percent; and 3,617 white students, or 75 percent.

Maxine Alpart, a student on the DEI Committee, said, “I feel like our school is very divided right now …. You can’t have a civil conversation.” She added, “Sometimes, I just want to get to class.”

Alpart is one of two students who organized the first anti-hate rally at Guilderland High School, in May 2021. She said at that rally — in which students shared a lifetime of hurt — that the term “Wasian,” which means white Asian, had been used many times to exclude her from both groups.

Pinchinat, then a history teacher, helped organize the rally; Wiles and Piscitelli attended as did other administrators and school board members that first year and the following year as well.

In our culture, Alpart said at the rally, racism is brushed off as schoolyard teasing, which invalidates the experience. “We need to educate teachers," she said, "on how to provide safe spaces for students before they get hurt.”

Alpart, at Wednesday’s meeting, was pressed by other committee members about what was dividing students — race, culture, socio-economics?

One member asked if the division was between some students feeling the blackface incident was a big deal while others felt it was not. Alpart concurred, defining the division more precisely: “‘It’s a harmless mistake’ versus ‘they knew what they were doing.’”

She went on, “This was like a tipping point … The small thing that gave people the strength or motivation to say something.”

Alpart, who has worked with school activists on projects including the anti-hate rallies, said, after the blackface incident, she heard from people whom she’d never heard speak out before.

Tibisay Hernandez, who chaired the DEI Committee meeting, said that the straw that broke the camel’s back may not be the intention but it is important to acknowledge the impact. “If we don’t confront these issues, they are going to continue to happen,” she said.

Wiles then spoke about the equity teams in each of the district’s seven buildings and the work they are doing with Progressive Partners. Also Natalie McGee, chief executive officer of Progression Partners, is giving workshops and “equity walks” at each building to understand the “climate and culture” as action plans are developed.

Later, as the committee members discussed a book they are all reading — Amber O’Neal Johnston’s “A Place to Belong” — Hernandez said of our society’s lack of acknowledging racism, “You’re being gaslighted by an entire society.”

“Some of the microaggressions feel like getting mugged … The rage of it comes to you, years later,” said Hernandez, adding that she could understand why Guilderland High School students were now relating experiences from elementary school.

Rivera said that conversations she had after the blackface incident were “eye-opening” because some parents said their children would have understood not to wear blackface and why while other parents said their kids wouldn’t know that.

So, yes, a school is not an island. Racism is all around us. It takes a larger community to combat it. Racism, like charity, begins at home.

It may not be intentional — but it still hurts. Hernandez said she underlined this sentence in Johnston’s book: Children follow our example, not our advice.

Committee member Elizabeth Floyd Mair said it is not doing children a service to teach them “we’re all the same deep down …. It’s important to look at race and talk about it …. It should be acknowledged and respected.”

Maybe it’s not either-or, a choice — but both. Yes, we are each individuals and our race helps define us. But we are also part of humanity at large — and must respect other people as such.

Committee member Louis Zuoguang Liu said, when he was trying to correct his second-grade son’s habits, his son said, “Everyone is different.”

Liu said, “I was raised in a society where everyone was asked to follow the discipline.” That his son emphasizes differences worries him a bit.

Hernandez responded with a story about her own young son. When he doesn’t want to go to bed at his set bedtime, she asks him how that serves the entire family, to have him grumpy in the morning when everyone needs to get on their way.

So, yes, we are each individuals with our own needs but we are also part of a larger society and need to serve the common good.

Wearing blackface, whether intentionally harmful or not, was hurtful.

The school district is wise to seize this moment and, as it has, inform the community so we can all work towards respecting one another.

We can finally answer the call Elizabeth Graham made nearly a quarter-century ago: “I ask that my community would first recognize the problem and then to mentally and spiritually join me in the healing process. Few things are done overnight. Purging racism from one’s mind is not one of them ….”