Two new Americans talk about their stories

ALBANY — Abdi Nor Iftin, a Somali refugee in Kenya, won a green card to emigrate lawfully to the United States in the diversity visa lottery, but first he had to survive violence and near-starvation to make it to his embassy interview three months later.

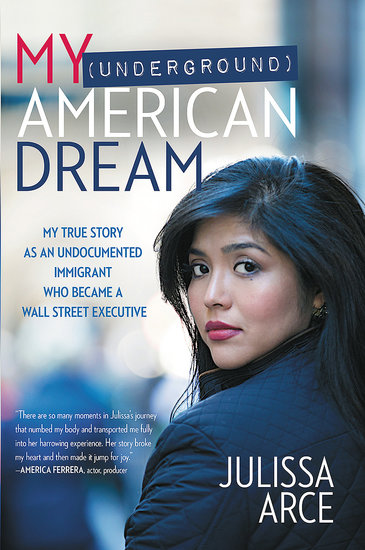

Julissa Arce was brought to the United States as a girl of 11 by her parents, undocumented immigrants from Mexico. She worked long hours helping her parents keep their business afloat and, at the same time, made it to university and then to a position as an analyst at Goldman Sachs, all while harboring the secret of her precarious legal position.

Each has written a book, taking a personal look at the hot-button topic of immigration. Both Iftin and Arce will appear at the University at Albany on Saturday, Sept. 29, to speak on a panel called “New Americans,” from 2:45 to 3:45 p.m. in the Campus Center ballroom, as part of the Writers Institute’s Albany Book Festival.

Also on the panel will be two more authors, Gold Star father Khizr Khan, speaking about his book, “An American Family: A Memoir of Hope and Sacrifice,” and Maeve Higgins, host of the hit podcast “Maeve in America: Immigration IRL” and the author of “Maeve in America: Essays by a Girl from Somewhere Else.” The panel will be moderated by memoirist and teacher of memoir writing Marion Roach Smith.

Both books are about people who overcome challenges through determination and luck to make their voices heard. As Arce writes, “I know I’ve made it because I’ve earned the right to question the system in which I live. I’ve made it because I’ve earned the right to have my voice be heard.”

Arce’s shadow life

Julissa Arce’s book opens with her having a panic attack over the impending start of her job, straight out of college, as an analyst at Goldman Sachs, because she knows it will mean being fingerprinted, and submitting false identification documents.

“Everything I’d done in my entire life, every accomplishment, every dream could disappear the moment I walked through those doors,” she writes.

But she isn’t caught. She performs well under pressure and rides the fast track to responsibilities unheard of at Goldman Sachs for a first-year analyst.

Meanwhile, she has no driver’s license and needs to show her Mexican passport each time she goes out for drinks with colleagues, hoping that they won’t notice. And she lives in fear, since her visa has long-since expired, that her bosses will ask her to make a quick visit to the company’s London office.

Julissa Arce came to the United States when she was 11, brought by her parents, and then lived for many years in the shadows of undocumented immigrant status, rising to a position as an analyst on Wall Street.

Eventually Arce marries, which brings her a green card, and she simply resubmits her now-legitimate paperwork to her company’s human-resources department, which doesn’t question the new Social Security number.

She leaves Goldman Sachs to start her own travel website, goes back to work briefly for another financial firm, and then decides that, more than trying to become rich, she wants to try to help other undocumented immigrants and, she writes, “change the conversation on immigration in this country.”

She now writes full-time, she told The Enterprise, and also continues to work for a scholarship and mentorship fund she co-founded and now chairs, the Ascend Educational Fund. The fund provides scholarships to students irrespective of their immigration status.

She told The Enterprise that most of the students in the program are undocumented immigrants, but some are the first-generation children of two immigrants to the United States.

She also hosts a podcast called “Defining Us,” through Crooked Media’s Crooked Conversations series, exploring issues related to the accomplishments and struggles of Latin American people in the United States.

Watching the turn that the national conversation about immigration has taken in the last couple of years, while “frustrating and painful,” Arce said, has also been “energizing” and has given her added impetus to continue the work she does.

“The work is not done,” she said simply.

People often ask her, she said, why she didn’t come out of the shadows earlier. She said that this is a frustrating question, based in the idea that undocumented immigrants are just too lazy to do the work to become a citizen.

She said that there is currently no path to citizenship — without a national DREAM Act — for children who didn’t choose to come to this country but were brought here by their parents, who have grown up here and know nothing of their native country.

Arce told The Enterprise that the millions of undocumented immigrants in this country provide the federal government with massive amounts of money without ever receiving services from it. Taxes taken out of undocumented immigrants’ paychecks every week, intended for the Social Security fund, will never come back to them; the amount that these workers paid into this fund over the last decade is $100 billion, she said.

Likewise, undocumented immigrants in the United States pay between $10 and $12 billion a year in state and local taxes, she said. She writes in her book, “I wondered sometimes how to reconcile that with the idea of ‘no taxation without representation,’ which I’d been taught in my American history classes.”

Iftin’s journey from Somalia

Iftin was born to parents who had been proud nomadic herdspeople in the Somalian bush until drought and war forced them in 1977 into the capital of Mogadishu, where Iftin was later born, according to his memoir, “Call Me American.”

Like all Somalis, Iftin does not know his exact birthday, but he estimates he was born in about 1985, which would make him 33 today, and he selected June 20 as his birthday when he needed one for his Kenya refugee registration forms. To Somalis, Iftin writes, “There are only two days: the day you are born, and the day you die. Everything in between is herding animals.”

Iftin grows up listening to his mother’s spellbinding stories of facing down hyenas and lions to protect her many goats and camels, but in Mogadishu his family faces very different, more constant threats. The eruption of civil war when he and his brother are children of about 6 and 7, and their sister young enough to be wrapped on their mother’s back, makes them leave their home on foot, fleeing the hostilities.

Their family splits up, their father going into the bush alone, since he would make the family a target for soldiers. Along the way, the children and their pregnant mother see death everywhere: Stray dogs chew on dead bodies in the street; a soldier casually shoots a hostage in the head as they pass by; and badly injured people simply lie down to die, since the hospitals have been destroyed.

They are taken in by a relative whose home in Mogadishu is intact. Abdi and Hassan must go every night to fetch water, when the snipers lining the road who shoot at people for practice would be unable to spot them.

Soon after she is born, Abdi’s baby sister, Sadia, dies a slow and painful death of hunger and thirst, since their mother has no drops of milk to give the child, and Abdi and his brother bury her in the front yard.

By about late 1992, a semblance of normalcy returns to the city as people move into abandoned houses. Abdi begins hanging out at a makeshift movie shack whose owner shows VHS tapes of American films like “Terminator” and “Rambo.” By watching them over and over, Abdi starts to learn English phrases, consisting largely of curse words, he writes, like “I’ll be back,” “Get the f--- out of here,” or “Motherf-----, my name is Abdi American, I am a powerful man. Be careful.”

He adorns his room with torn movie posters from the ruins of the local cinema, and goes by the nickname Abdi American. He despises the madrassa his mother forces him to attend to learn to memorize the Koran, coming to prefer hip-hop and boom boxes to religious strictures. He longs for the day when Rambo and the Terminator will come to Mogadishu and blow to smithereens all the heavily armed zealots.

Their younger sister, Nima, is married off at 14 to an older man, and clan militiamen and strict Islamists vie for control of the city, with the Islamists forcibly recruiting young men for training. Abdi’s brother flees for Kenya, hoping, like other refugees, to go on from there to Europe or the United States.

Amid the unrest, international journalists start coming to Somalia and Abdi Iftin, now 22, argues his way into a heavily guarded building to meet one of them, a Pulitzer Prize-winning BBC reporter, Paul Salopek.

This is the start of his work as a reporter-on-the-street from Somalia, recording on a small tape recorder in his room. His work — for which he could easily be killed — then expands, to include an American public radio show called “The Story.”

Of his life in Somalia, Iftin told The Enterprise, “I don’t think there’s one day that I never feel fear.”

Later, he joins his brother in a refugee camp in Nairobi, Kenya, and they try every avenue they can think of to get a visa to go overseas.

Life in the refugee camp is better than Somalia for the brothers, until an attack by the Somali Islamists of al-Shabaab in a Nairobi shopping mall causes the country’s president to crack down on Somali refugees and demand their deportation. Kenyan police begin roaming the projects, which Iftin told The Enterprise were “spooky” and “empty,” looking for Somalis.

Iftin told The Enterprise that the government of Kenya had decided not even to try to separate terrorists from refugees, but simply to equate all Somalis with the radical Islamists whom he had left his native country to escape.

Eventually, Abdi and Hassan hear of the “diversity visa lottery,” through which 155,000 people from countries around the world are selected for a chance to apply for 55,000 American green cards. In 2013, they and all their friends apply, as do about 8 million to 15 million people in the world each year.

But before Abdi can make it to his embassy interview three months later, in hopes of becoming one of the one-in-three to actually get a green card, he must collect an array of official documents — including one from the very Kenyan police who are hunting for Somalis like him. He and his brother spend the three months holed up in their apartment in the deserted refugee area, nearly starving, with Abdi sneaking out only when he desperately needs to, to try to obtain the documents.

Through a combination of determination, grit, and luck, Abdi eventually gets the visa and makes it to the United States, where he now lives in Portland, Maine and works as an interpreter, helping newer Somalis with doctors’ visits and court appearances.

Iftin plans to live in the United States permanently, and to begin the process of applying for citizenship next year, when he will be eligible, having lived in this country for five years.

He has spoken with immigration officials numerous times and been assured that he would be allowed back into the United States if he went home for a visit, but he is not taking any chances, because of the Trump administration’s ban on allowing anyone from Somalia to enter the country.

Iftin hopes that, in the coming years, with a new administration, the ban against Somalis may be lifted and he may be able to apply for family members to join him in the United States.

He is aware that the Trump administration is contemplating doing away with the diversity-visa lottery. He believes that putting an end to the lottery would play into the hands of radical Islamists, by slamming a door in the face of desperate and hopeless young men like himself, sending them into the relative protection of ISIS, or al-Shabaab, or Boko Haram.

Iftin says simply, “The lottery saved my life.”