In 1917, New York City bid farewell to 25,000 National Guard Troops with massive parade

More than 400,000 New Yorkers served in the military during World War I, more than from any other state. In observance of the war’s centennial, the Division of Military and Naval Affairs is issuing releases noting key based on information provided by the New York State Military Museum in Saratoga Springs, which The Enterprise will run from time to time.

****

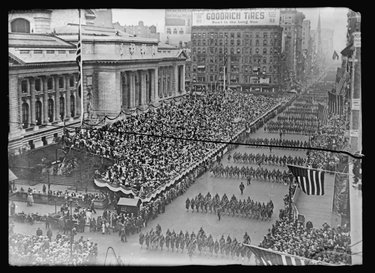

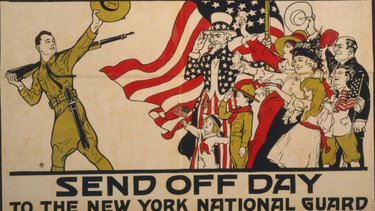

Before they walked down the gangplank onto French soil in April 1918; twenty-five-thousand New York National Guard Soldiers walked down Fifth Avenue in August 1917 so New York City could say goodbye.

On Aug. 30, 1917, hundreds of thousands of New Yorkers lined a five-mile route from 110th Street to the Washington Square Arch as the 27th Infantry Division paraded down the street.

There were so many marching soldiers, The New York Times reported, that it took five hours for the parade to pass by.

After being federalized on July 15, 1917 New York Army National Guard members remained at their armories, being issued equipment, undergoing medical checks, shoeing mules, and beginning to train for war.

The units also continued final recruiting efforts to bring their companies and regiments up to full strength. Local men were urged to go to war with their friends and neighbors instead of waiting to be drafted or enlisting in the Regular Army.

In Saratoga Springs, for example, Louis Dominick decided to join the local National Guard company at the last minute instead of enlisting the “depot company” the Army had established for the county. Dominick’s decision meant the regular Army recruiters were now one short of their goal of 50 soldiers for the county, The Saratogian reported.

While the Regular Army officers who were orchestrating mobilization wanted the soldiers to move into field camps quickly, the New York National Guard argued that it made more sense to use its armories for the mobilization process instead.

“These measures could be taken in a much more efficient manner in the great armories of New York State than they could in open fields, while commands were endeavoring to make camp with ranks augmented by many recruits and without military property adequate for their strength,” Major General John F. O’Ryan, the 27th Infantry Division commander, wrote after the war.

Initially, O’Ryan was told that his division — destined to be known as the 27th Division but still being called the 6th Division by the Army — would be training at Camp Wadsworth in Spartanburg, South Carolina and was slated to move in early August.

With this early August departure date in mind, New York City’s movers and shakers began planning for a big farewell parade. Initially the parade was set for Thursday, Aug. 9, 1917. But on Aug. 6, the division learned that Camp Wadsworth wasn’t ready yet.

The big parade was put off.

“If we lined the sidewalks of New York with the relatives of the soldiers — mothers, sisters and so forth, all crying and bidding goodbye to the boys — then the troops remained here for a week, maybe two weeks, the whole big impressive parade would become ridiculous,” New York City Mayor John Purroy Mitchell, told The New York Times.

The delay in moving south was probably a good thing, The New York Times also reported, since the soldiers of the 27th Division were still short of equipment and the units needed to be consolidated.

The men of the 71st Infantry Regiment, for example, were spread out in small elements over 700 square miles of upstate New York, The Times reported. It would take 30 hours to concentrate the unit, the paper said.

On Aug. 23, O’Ryan was informed that the division would move south beginning in early September and the big parade in New York City was back on again. Only now the festivities would include a dinner for 24,000 New York National Guardsmen as well.

Regiments from upstate New York were moved down to Van Cortland Park. Other regiments camped at Pelham Bay Park, Prospect Park in Brooklyn, and Bay Ridge, Brooklyn. Three coastal defense regiments — soldiers trained to man the forts that still protected New York City in 1917 — were on duty there.

On Aug. 28, Mayor Mitchell hosted a dinner at the Hotel Biltmore for O’Ryan, his division staff, and unit commanders. On Aug. 29, a committee of 100 Prominent Women played hostess at the camps around the city as the rest of the New York National Guard troops enjoyed “farewell rallies around feast laden boards,” in the words of a New York Times reporter.

“Only a town like the City of New York could seriously undertake a hospitality of such magnitude,” O’Ryan wrote.

The big parade kicked off at 10 a.m. on Aug. 30.

Members of soldiers’ families were given a special pass that allowed them access to the west side of Fifth Avenue from 110th Street south to 59th Street. Locations at the Plaza Hotel, the Pulitzer Memorial, and Madison Square were also reserved for soldiers’ families. Each soldier got four passes for his family members.

The New York Police Department was geared up to handle an expected two million spectators with 4,000 officers under the command of nine inspectors stationed along the parade route. Chief Inspector James Dillon, the officer in charge of the parade, issued an order forbidding the public from using “boxes, barrels, chairs, camp stools or settees of any kind” while watching the parade.

The Police Department Band led the parade, which allowed all the regimental bands to march with their parent organization.

First in line was the 22nd Engineer Regiment. The regiment’s A Company had already been ordered to Yaphank on Long Island to build a camp which would eventually be occupied by the newly formed 77th Infantry Division. Its D Company was already in South Carolina helping to finish Camp Wadsworth.

The rest of the regiment was due to get on a train after the troops marched past the reviewing stand at the Union League Club, and head south to help finish up construction of the post.

At the reviewing stand, Mayor Mitchell, former President Teddy Roosevelt, and other state and local dignitaries waved and greeted the troops.

The marching troops remembered cheering crowds, with people waving flags and shouting themselves hoarse, while “bombarding” the troops with “candy, chewing gum and all kinds of fruits, cigars and cigarettes.”

Most of the troops in the parade finished their march and went back to camp to wait for their turn to go to Spartanburg. The men of the 102nd Ammunition Train, for example, finished up marching in late afternoon and then boarding an elevated train to head back to camp.

A New York Times writer called the parade: “A thrilling, stirring sight!”

“File upon file, hour after hour, of well-set, clear-eyed, determined men, some young and yet to be hardened in training camps, others, and many of them, made fit already by experience to take up their final training in the fields and trenches behind the battle lines in France,” The New York Times said.

“We have never faced such a war as this, we have never had such an Army as we now have in the making,” The Times added.

For the next couple of weeks, the big parade of Aug. 30 was replicated several more times on a smaller scale as individual regiments left New York for Spartanburg.

The 7th Regiment's march to the train station on Sept. 11, 2017, for example, even included a second march past the Union Club for a sendoff by New York City’s great and good.

With the parade and send-offs behind them, the soldiers of the 27th Division adapted to their new home in South Carolina and began to learn the art of soldiering in the 20th Century. There would be much hard fighting in France ahead in 1918.