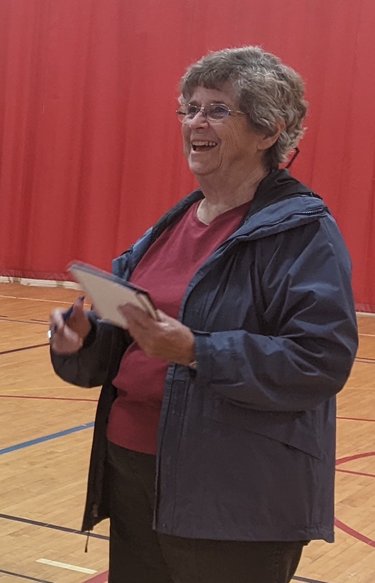

Slack to resign from Guilderland School Board after a lifetime of supporting kids

GUILDERLAND — Judy Slack has contributed to the Guilderland schools for over four decades.

At age 80, she has decided to step down from the school board with nearly two years left of her three-year term.

“I’ve done enough,” she said this week. “Enough is enough.”

She also said, “I’ve had a good life.”

Slack has spent that lifetime supporting others — babysitting in her youth, becoming a teacher as a young adult, raising her own three children as she worked for decades as a teaching assistant in the Guilderland schools, and finally serving on the school board for 16 years.

She started thinking about resigning from the board after undergoing knee-replacement surgery, causing her energy to flag.

Her resignation will take effect on Sept. 11, just after next month’s school board meeting. Over the summer, she talked to the superintendent about resigning, Slack said, and they agreed that fall would be the best time “to find a good candidate” to replace her.

The post is unpaid but elections were hotly contested in 2022 and 2024. The last time Slack ran, in 2023, none of the three incumbents faced a challenge. Slack hesitated to run again, saying she was gathering signatures to run but wouldn’t pursue another term if a suitable candidate arose.

“I love this district,” Slack told The Enterprise this week. “And I’m proud, proud, proud to have been a part of it.”

All three of her now-grown children — Julie, Sarah, and Tom — are Guilderland graduates and Slack has said that, growing up, they had varying educational needs, all of which were met at Guilderland.

A through-line in Slack’s life has been caring for children.

She grew up in Ithaca, one among seven siblings. Slack had two older sisters and four younger brothers.

Her mother, trained as a nurse, was a full-time homemaker and her father was a salesman for what became Agway.

“I was the babysitter,” said Slack — not just for her brothers but for the neighbors. She knew how to “keep their kids doing things and cheerful.”

“We didn’t have a lot of money,” Slack said of her family, “but I always had enough because I babysat all the time … Back then, you could get a dollar’s worth of gas and drive the car for as many miles as your parents would let you so you didn’t have to have a lot.”

Slack always loved school. “I wasn’t a great student — I was having too much fun. But I loved, loved school. I loved going to school and being around people — that’s always just the way I’ve been.”

Passionate reader

Slack’s favorite teacher was Elizabeth Whicher, who taught English.

“I decided if I could help a kid learn to love something like she helped me love reading, then that would be what I wanted to do. So I was sort of following her lead.”

In the summer before Slack’s senior year of high school, Whicher’s husband committed suicide, leaving her a widow with four children. Shortly after, another English teacher at Slack’s school also committed suicide.

“But she was always there and up,” Slack said of Elizabeth Whicher. “She was wonderful, loving, gentle, and had a good sense of humor.”

At an open house early in Slack’s senior year, Whicher told the parents of her students that she wished, instead of giving homework assignments, she could instead just require students to read for a half-hour each night.

“My parents told me that, so I went to school the next day and said, ‘That would be great.’ And so our assignment then was we got to read for half an hour every night …Doing that every night, you know, you do begin to love it.”

Slack’s favorite book, which was newly published at the time and has since become a classic, is Harper Lee’s “To Kill a Mockingbird.”

“I love Atticus,” she said of the lawyer in the fictional small southern town where the book is set, similar to the town where Lee grew up. Atticus Finch defends a Black man wrongly accused of raping a white woman.

The story is told by Scout, Atticus’s daughter. “I like the goodness of the characters … I just love them; I feel like I know them,” said Slack. “And I like the growth of Scout from being a little kid to what she has to witness and how she grows through it.”

Slack taught the book when she herself became a teacher. And more recently, in 2017, when she took a cross-country trip with her grandchildren, she read it to her 12-year-old grandson.

“Coming back through Nebraska, you know, where it’s just endless cornfields, I read ‘To Kill a Mockingbird’ to my grandson and he just loved it. When he went back to school in the fall, his teacher had the kids write a report about a book they read over the summer; they had to tell the pros and cons of the character they liked most.”

“I would write about Atticus,” her grandson said. “But there were only pros about him. There are no cons.”

Becoming a teacher

Slack went to Russell Sage College in Troy where she majored in English. She called it “a perfect fit for me.”

Slack continued her babysitting, including for one of her professors, and was struck with the seriousness of one of her favorite teachers, Russell Barker.

“In one class, Dr. Barker asked two students just a very simple question about what was going on in the book, and they hadn’t read that night’s assignment. He picked up his books and he crossed his arms in front of him, holding the books, and he looked at us and said, ‘Get out.’

“And we all kind of looked around, and he said, ‘Get out. The purpose of this class is to discuss what you’ve read and, if you haven’t read it, I have nothing to say to you.’”

The students did as they were told and left the classroom. “It was awful. We all just were in shock … Nobody ever missed an assignment again,” Slack recalled.

She did her student teaching at Troy High School and then got her first full-time teaching job there.

“I loved it. I loved the kids,” said Slack. “After I’d been there a month or two, one of the students, a brother of a girl I had in class — he was big, a Black kid on the football team — came up to me and said, ‘Listen, Miss Bonney, if anybody gives you a bad time, you tell me. I’ll take care of him for you.’”

“How can you not love that?” asked Slack.

At age 22, in 1966, Slack was earning $4,800 a year. “That’s not even $100 a week,” she said. “I was living at Russell Sage as a dorm counselor so I didn’t have any housing expenses or food costs.”

After her first year of teaching, she worked in the summer in an Upward Bound program at Union College. “It was to help needy students hopefully get into college,” she said.

After her second year of teaching, she was asked to be the assistant director of Upward Bound so she left Troy High School to do that.

Meanwhile, through her brother who had been a student at RPI, she met Joe Slack, an RPI student who would become her husband.

“We got married just before the end of his senior year,” said Slack.

He had majored in engineering and then taught math and science courses at Berne-Knox-Westerlo while Slack taught English courses at BKW.

“Yesterday, we were at a picnic with the kids — I still call them kids; they’re all retired grandparents now — but we’re still friendly after more than 50 years,” she said.

Making a difference

Slack stopped teaching when she became pregnant with her first child, Julie, who just turned 50.

The Slacks settled on Leesome Lane in Altamont, in a house built by Joe Slack.

Judy Slack started volunteering in the Guilderland schools until she became employed by the district as a teaching assistant; she did that job for 24 years.

“Being a teaching assistant was the perfect job for me,” said Slack. “You don’t have a huge salary but you get to work with kids all day, you make a difference, and then you come home and at the end of the day, you don’t have all the work that a teacher has.”

She went on, “I’ve helped teachers do a better job just by being there, helping take care of kids who otherwise would take too much of the teacher’s energy.”

One of the students she had taught at BKW had a child at Lynnwood Elementary School when Slack was working there as a teaching assistant.

“The first thing she said to me was, ‘I still remember “To Kill a Mockingbird” … It’s the best book I ever read in my whole life.’”

When Slack’s oldest child, Julie, was in the sixth grade, she came home from school one day and told her mother, “I’d like to go to the board of education meeting tonight and represent the views of sixth-graders.”

“She didn’t like it because the teachers were doing work to rule,” Slack recalled. “And I thought, if my daughter said she wanted to go to board of education meetings, maybe I ought to start going myself.”

And she did. Slack would regularly attend meetings, listening intently from the gallery.

When Julie was a senior in high school, said Slack, “she started going to the board and telling about what was going on at the high school — and that tradition is still carried on.”

Once Slack retired, she ran for the school board and has served for 16 years.

Asked what she is proudest of in all those years, Slack said, it is hiring Marie Wiles as the district’s superintendent.

“What a difference she has made in terms of the district and what people think of it …. Everybody gets along much better than when she came on. There was some real turmoil and it took awhile to calm that down. The staff respects her a great deal and so does the community at large.”

Slack also thinks the district’s initiative towards diversity, equity, and inclusion over the last several years “makes a huge difference.”

She primarily sees her role on the school board as having been a supporter of the district.

“I love to go to events that the students are doing …. I always volunteer to be on committees so I can get to know the people in the community and the teachers and just to feel like I’m part of what’s going on,” she said.

“I’m no longer working, so this is my job. I love seeing the kids with their joy and enthusiasm and I love hearing their concerns.”

Slack cited an example of students speaking to the board about having a menu for school meals that better serves different ethnicities of students.

“We learn from them,” said Slack of the students, “and make things better for them.”