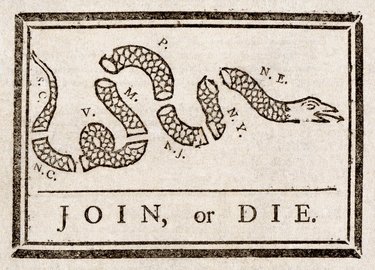

History teaches us the value of compromise

Good governance requires compromise. This is true at every level in a democracy.

Looking at the compromises involved in the very formation of our nation can be instructive even when considering local governance.

Created in 1777, the Articles of Confederation and Perpetual Union established a “firm league of friendship” among the 13 states, once colonies, that had formed a new nation. Delegations from each state were members of Congress, with each state getting one vote, but consequential decisions required a unanimous vote.

This paralyzed the government, rendering it ineffectual. If everyone has to agree, nothing moves forward.

Hence delegates from each of the 13 states save Rhode Island convened in Philadelphia to draft a constitution that would create a government with enough power to act nationally without so much power that fundamental rights would be at risk.

In our Constitution, powers that are not assigned to one of the three branches of government — legislative, executive, and judicial — are reserved to the states.

As the framers of the Constitution hammered out the formation of the legislature, two plans emerged: the New Jersey plan, favored by the smaller states, which gave each state a single vote, and the Virginia plan, favored by the larger states, which based representation on the population of each state.

The Great Compromise gave us the system we still have today with two houses: the Senate where each state, regardless of size, has two representatives, and the House of Representatives, where the number of legislators is based on a state’s population.

But more compromise was needed to create a functional government.

Once the Constitution was written, 39 of the 55 delegates signed it with many of the refusals because of the lack of a bill of rights. The Constitution had to be ratified by nine of the 13 state legislatures.

As the debate over ratification raged on, two factions emerged: the Anti-Federalists in opposition and the Federalists who supported adopting the Constitution. A major sticking point was that the Constitution had no list of basic civil rights.

Ratification in several states depended on the adoption of a bill of rights. In what became known as the Massachusetts Compromise, four states ratified the Constitution on the premise that a list of rights would be added.

The 12 suggested amendments, winnowed to 10, were based on the Virginia Declaration of Rights, the English Bill of Rights, the writings of the Enlightenment, and the rights defined in the Magna Carta.

The Bill of Rights was adopted by the First Congress in 1789, becoming the bedrock of individual rights and liberties in the United States of America.

With this history in mind, we can see how compromise at all levels of government can move things forward.

A recent local example can be seen in the twice defeated Berne-Knox-Westerlo school budget. After the first defeat of a budget that went over the state-set levy limit, requiring a supermajority vote to pass, the governing school board had one more chance.

Had the board cut the single position that pierced the cap, a school resource officer added late in the process, we believe the budget would have passed on the second try in June, requiring just a simple majority vote.

Of the 19 school districts in New York state that had budgets voted down in May, BKW was the only one that suffered a defeat in June; it was also the only district that still went over the state-set levy limit.

Had the governing board been willing to compromise, we believe the district would not have had to make well over half-a-million-dollars in cuts for the next school year.

That’s a tough lesson to learn and we hope other local governing boards will take note. In a compromise, both sides will not get everything desired but each will get something.

With that in mind, let’s look at the project proposed for a brownfield site in Guilderland.

Thirteen acres of land spread across five separate tax parcels between 2298 and 2314 Western Ave. have long plagued the town. Four different developments have been proposed for the site but the cost of cleaning up toxic waste left by a defunct dry-cleaning business has stymied those plans.

The contaminants have affected the groundwater and a tributary of the Hunger Kill.

The current proposal, by Guilderland Village LLC, is for a Planned Unit Development, to be called Foundry Square, with expensive housing and retail space in two four-story buildings.

The Guilderland Town Board, which will have final say on whether or not the project moves forward, was cool in its reception of the first presentation in May.

Neither the proposed height of the buildings, four stories, nor the number of units proposed, 22 units per acre, are allowed by Guilderland’s zoning, but in seeking a Planned Unit Development, the developer is able to ask the town board to approve both requests because PUDs do not have set limits on height or density.

The developer made the case that, in order to afford the cleanup, estimated at $2.5 million, as well as needed traffic improvements, he would need the increased density.

Currently, 10 percent of the proposed units would be for workforce housing to accommodate, say, teachers or police officers, while several board members requested a higher percentage for workforce housing.

As a newspaper, we’ve frequently pointed out the need, on this page, for affordable housing and congratulate Guilderland on recently becoming certified as a Pro-Housing Community, making it eligible to apply for state grants to increase affordable housing in town.

But is it wise to hamstring a developer who is willing to take on a problem that affects many current residents — toxic waste?

Ten-percent workforce housing looks to us like a step in the right direction as other developers in town have offered none.

The largest issue here is the brownfield that continues to pollute, as it has for decades, the land and water in central Guilderland.

We were concerned when we learned the developer’s plan is not to remove the contaminated soil but rather to use an oxidation process to neutralize it. Enterprise reporter Sean Mulkerrin delved into the matter and wrote a primer on how the oxidation process would work to clean up a brownfield.

We are convinced that Guilderland’s planning board and town board should consider this as a viable option to a problem that has plagued the town for too long.

In March, Theresa Bohl had addressed the town board about the properties as she is the “inherited major shareholder of Charles Bohl Inc., which is 2298 through 2314 Western Avenue — everyone’s favorite property,” she said.

Bohl noted that her family hadn’t been the cause of the pollution, having bought the dry cleaners in 2011 to satisfy a potential buyer.

“Since 2013, I have been working with DEC and trying to get that site remediated … Everyone has kind of passed so I’m left holding the bag,” said Bohl. “We have spent over a million dollars remediating the old gas-station site.”

She went on to say that the corporation that owns the properties, Charles Bohl Inc., is bankrupt and owes $1.5 million to a lender. “The property is selling for less than that and I stand to get zero out of it …,” said Bohl.

She went on, “I personally am paying the taxes, $55,000 a year, just out of family pride. My family has been here since the 1920s and we built a lot of what is in this town. And through that poor judgment of buying that dry cleaner, we’ve really been kind of pulled through the mud with it.”

Bohl said the current “quality buyer” interested in the properties has “full eyes open.”

“This is kind of our last hurrah,” said Bohl.

In May, Bohl wrote a letter to the editor, saying, “Either this site is remediated and redeveloped or will we now do what any other person would have done years ago and declare bankruptcy and abandon the property and leave it to the taxpayers to pay for the remediation.”

We believe her estimate is correct that the site will be abandoned for at least a decade more as the county goes through the courts and the process to repossess the property.

We would urge both the developer and the town board to compromise so the project can move forward.

Yes, the town board should hold firm for the interest of Guilderland residents.

But, just as the BKW Board should have asked, does adding a school resource officer outweigh the many other valuable programs that may have to be cut, we believe the town board members should ask themselves: Does upping the 10 percent of workforce housing in the proposed new complex outweigh the chance to clean up this long-standing blight in town?

Compromise is the best way forward.