How would oxidation work to clean up Master Cleaners brownfield?

— From the Environmental Protection Agency

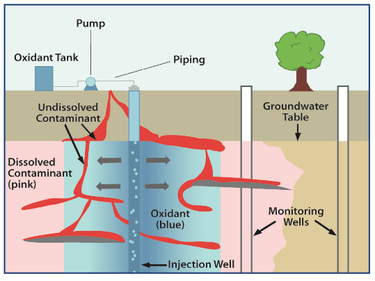

One process used in decontaminating brownfield sites is in-situ chemical oxidation, a process that typically involves the installation of wells at different depths in the affected area and pumping a chemical down the well, rendering the decontaminant inert. The process is under consideration to be used on the former Master Cleaners site on Western Avenue.

GUILDERLAND — The engineer for the developer looking to decontaminate and build 285 apartments at the corner of Western Avenue and Foundry Road recently told the town’s planning board how it would make that happen.

In late May, Daniel Hershberg told board members that the contamination plume runs through the center of the former Master Cleaners building, “then loops around and goes all the way down to the stream course at the back.”

A project memo submitted to the Guilderland Town Board by Town Planner Kenneth Kovalchik says the contamination “has already impacted a tributary of the Hunger Kill and is in close proximity to the Hunger Kill and residential properties along Foundry Road.”

The dry-cleaning operation was in business from 1956 through 1996. Albany County took title to the property in 2001, following a tax foreclosure. It was then purchased in September 2011 by current owner, Charles Bohl Incorporated.

Previous testing of the site found its “primary contaminants of concern” to be “chlorinated volatile organic compounds (VOCs), particularly tetrachloroethene (PCE), trichloroethene (TCE), and their breakdown products. PCE and TCE, widely used in fabric dry-cleaning, are non-flammable, colorless liquids at room temperature that evaporate easily into the air and emit an ether-like odor.”

Chlorinated solvents, like PCE and TCE, “are considered hazardous chemicals that are historically known as recalcitrant compounds that are exceedingly difficult to remediate unless the conditions are ideal for remediation,” according to the federal Environmental Protection Agency.

The solvents are known as “dense non-aqueous phase liquids” (DNAPLs), which are heavier than water, meaning they sink instead of float, which can make for a more difficult clean-up.

Recently, Guilderland Village, a limited liability company from the development team behind the luxury senior-living facility Hamilton Parc, became the latest in a line of developers looking to build at the site. The company is seeking approval from the town board to build two four-story buildings consisting of 285 apartments: 171 two-bedroom units and 114 one-bedroom units.

The site was added to the state’s list of designated brownfields in 2016.

A planning and development term used to describe previously-developed land that is currently unused or underutilized, brownfields are often former industrial or commercial properties that may be contaminated due to their past use.

The state defines a brownfield as any real property where a contaminant is present at levels exceeding the soil cleanup objective or other health-based or environmental standards, criteria, or guidance adopted by the state’s Department of Environmental Conservation, which said the former Master Cleaners site posed a significant threat to the public health and environment, and that cleanup of the soil and groundwater is required.

In May, Hershberg said to decontaminate the 13 acres of land spread across five separate tax parcels between 2298 and 2314 Western Ave., Guilderland Village LLC, “could always excavate all the dirt and truck it off-site, but this stuff is now 15 feet in the ground and it runs into a clay layer,” Hershberg said. “So we have to excavate all that area down to 15 feet deep and truck that off the site, which is neither economically feasible nor desirable. We’ll have all those trucks running back and forth across the streets to the places to dump them.”

Kovalchik’s project memo states, “Chlorinated solvents are present in soil and groundwater at depths up to 15 feet below grade. Groundwater is present at shallow depths ranging from 1 to 6 feet below grade depending on the season and location. There is a distinct confining clay layer at the site ranging from 11 feet to 15 feet below grade that appears to be limiting the vertical migration of contaminants.”

In-situ oxidation

So, rather than truck the contaminated soil off-site, Hershberg told the board on May 22, “We’ll use some chemical method. Oxidation is probably the way we’ll do it.”

Oxidation, he explained, is where “you put chemicals down that oxidize the chemicals in the ground, and that makes them inert. Then the problem goes away,” he said before adding, “I can’t commit to that plan yet because we still have to get the environmental review.”

Known as in-situ oxidation, the process typically involves the installation of wells at different depths in the affected area. Once the chemical is pumped down the wells, it spreads into the surrounding soil and groundwater where it mixes and reacts with contaminants.

In cases where the affected area has very low permeability, the oxidizing agent may be injected into the ground using a probe, about three-quarters to an inch-and-a-half in diameter, that is rotated or pushed into the ground while the oxidizing agent is inserted into it at low pressure.

The typical decontaminant used for chlorinated solvents is permanganate, a manganese compound known for its strong oxidizing properties.

Although outcomes are exclusively site specific, one federal study that examined 235 contaminated sites found those that used permanganate, saw a median reduction at about 84 percent.

Following treatment, contaminant concentrations can begin to creep back up or “rebound,” necessitating the need for another treatment, which is not an uncommon occurrence. Rebounding occurs when an oxidant doesn’t reach all of the contamination, and can take several weeks to months to detect.