Taser fired at traffic stop

A Facebook video of a New Scotland traffic stop, shown by local television news shows and picked up by the liberal activist news service Alternet.org with the headline, “Cop can’t wait for his backup to arrive so he could needlessly tase a nonviolent man,” has raised questions about the danger of traffic stops for officers and about the rights and responsibilities of both police and civilians.

“You never know what’s on the other side of that door,” said Altamont Police Chief Todd Pucci. “That’s why night is probably the scariest time to stop a car.”

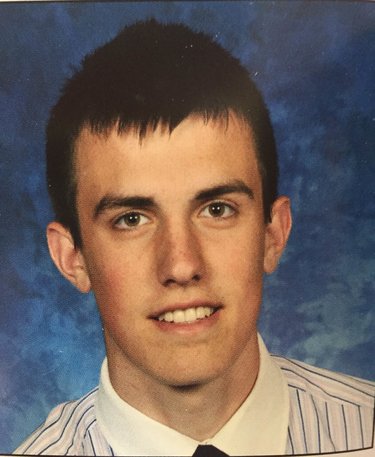

The Facebook video was made on June 21 at about 2 a.m. when New Scotland resident Christopher Dimmitt, 22, was stopped by Albany County Sheriff’s Deputy Philp Milano for speeding. The encounter, in Dimmitt’s own driveway, quickly escalated into a tense series of commands that went unheeded and questions that went unanswered, as well as repeated threats from Milano that he would tase Dimmitt.

The encounter ended after another officer arrived on the scene, at which time Milano tased Dimmitt and then arrested him on a number of charges: four misdemeanors — second-degree obstructing government administration; driving while intoxicated, first offense; driving with a blood alcohol content of .08 percent, first offense; and resisting arrest, and two infractions — speeding, and illegal signaling.

The Albany County Sheriff’s Office has completed its investigation of the use of force in the June 21 stop and concluded it was within agency standards and guidelines, said Chief Deputy Michael Monteleone of the Professional Standards Unit.

The criminal charges are still pending against Dimmitt in New Scotland Town Court, where he is scheduled to appear on July 16.

The Facebook video taken by a passenger in Dimmit’s car, Eric D. Weinstein, is hard to interpret — shaky, filmed facing the flashing lights of the police car and from an awkward angle behind Dimmitt and Corey Hughes, another passenger. The video starts at 1:52:46 am, more than 30 seconds into the verbal exchange among Milano, Dimmitt, and Hughes.

Much clearer is the video from the police car’s dashboard camera provided to The Enterprise by the office of Albany County Sheriff Craig Apple. The dashcam video, posted on the Enterprise website with this story, shows the entire encounter from start to finish. The most crucial part of the video is the first four-and-a-half minutes, from the time when Milano first speaks, at 1:51:55 a.m., through the tasing, at 1:56:21 a.m.

Dashcam view

The dashcam video shows Dimmitt and Hughes refusing numerous times to follow Milano’s commands to get back into the car. They say they haven’t done anything wrong, and that there is no reason to order them back into the car.

The video also shows Milano taking a confrontational stance from the very beginning, quite possibly before Dimmitt has any idea that this is even a traffic stop. Milano threatens to tase Dimmitt within the first 15 seconds of the encounter, and fails to state his reason for being there — that it was a traffic stop and that Dimmitt had been speeding — until almost three minutes into the heated encounter.

The sheriff’s video also shows that, when Milano tased Dimmitt, Dimmitt had his arms raised at the elbows, hands at about shoulder level, and was not advancing at all, and Hughes had his hands, with fingers interlaced, on his head. The deputy never touched either young man, and made no effort to take them into custody without tasing.

Milano, Dimmitt, and Hughes all declined to comment for this story.

The dashcam video shows Dimmitt’s car go by in the opposite direction on a two-lane road in the dark and rain, and Milano making a three-point turn to follow it.

Milano’s reason for turning to pursue the car, Dimmitt’s arrest report states, was that he had estimated Dimmitt’s speed at 50 in a 35-mile-per-hour zone; “the actual speed of the vehicle was confirmed to be 47,” the report says. According to the report, Milano had been traveling east on Krumkill Road, in the vicinity of Hilton Road, when he made the three-point turn.

On the dashcam video, Dimmitt’s car goes down a hill, out of sight, and very soon afterward —beyond the range of the camera — pulls into Dimmitt’s driveway at the intersections of Krumkill and Normanskill roads in New Scotland. This intersection is just 0.3 miles from the intersection of Hilton and Krumkill, where Milano first saw Dimmitt’s car.

Milano then reaches the driveway and pulls into it. He writes in the arrest report that it was at this point that he turned on his lights, although it is hard to tell, in the black-and-white video, just when the police car’s flashing lights are turned on.

The arrest report says that Milano saw the vehicle pull into the driveway, “failing to signal appropriately.” The report continues, “I activated my emergency lights and pulled behind the vehicle to initiate a vehicle and traffic stop.” So it would seem that Milano did not activate his car’s flashing lights until pulling into the driveway.

At that point, Dimmitt and passenger Corey Hughes are climbing out of their car. There is nothing defensive or combative in their posture; they look a little tired. They look like people who have just realized that there is a police car in the driveway, and who have no idea why.

They are greeted, when they get out, by Deputy Milano commanding them, off camera, over and over, to get back into their car. They look surprised. Dimmitt asks, “Why do I have to get back in the car?”

Milano says, “Get back in the car, or I’ll tase you.”

Dimmitt says, again incredulous, and this time with a bit of a laugh, “You’ll tase me?”

Hughes raises his hands, but neither young man makes any move to get back into the car. In fact, Hughes takes a few steps forward, but he still looks to be at least about 10 feet from Milano. Dimmitt is probably about 6 feet away from Milano. Neither is advancing towards the officer.

Dimmitt again says, “Give me a reason to get back in the car; I didn’t do anything wrong.”

Milano says into the radio that he has his Taser on two of the subjects, and that they are refusing to get back into the car.

Hughes says, “No, we’re not refusing. We’re just standing.”

Dimmitt again says, “I’m not a threat. This is my house.”

Milano, for the first time, says something that could indicate that he feels outnumbered: “I’ve got two of you that need to get back in the car now.”

At 1:53:31 a.m., Hughes says, “I dare you to tase me.” He has his hands up above his head. He gestures toward the police car — presumably toward the dashboard camera — and says that all of this is being recorded, and adds, “Dude, I’d love to see it.”

Hughes moves sideways towards Dimmitt, telling Milano to put the sight on his chest instead and to tase him rather than Dimmitt. Moving a few steps closer to Dimmitt has brought Hughes a few steps closer to Milano, but he still has his hands above his head.

Milano tells them both to step back, and Hughes does, to his original position. This is when the third male passenger — Weinstein — gets out of the car, holding up a cell phone, starting to record the encounter from about 6 feet behind Hughes.

Hughes says, “Can I ask why you’re pulling us over?”

Milano is talking on the radio, saying that there are five people total at the stop, and that two of them are out of the car and refusing to get back in. He says that he has his Taser on them.

Dimmitt says, with a mystified expression and an irritated tone, gestures toward his house, saying, “There has to be a reason. This is my home. I’m home.”

Milano says, “We’re gonna stand just like this, till my backup comes.”

Weinstein, holding the camera, says, “Sir, can I ask you why you have your gun pointed at my buddy?”

Hughes pivots his torso back around toward his friends, and someone says to Weinstein, “No, you get back in the f---ing car.” (It seems to be Hughes who says this to Weinstein, although since Hughes’s face is not visible, and Milano is off-camera, it is hard to tell.)

Dimmitt says, “I want to know why you have a stunner pointed at me.”

Milano says, calmly, “Because you’re refusing my commands right now.”

Hughes asks Milano several times for a reason, and Dimmitt tries to calm down his friend. Milano advances toward them, Taser pointed at them, and yells, “You need to just shut up right now, OK? There’s five of you, and one of me. I don’t know what you guys are doing. You need to just shut up right now, OK?”

This is the first time Milano appears on the camera. Only one part of the officer is visible: his hands holding the Taser outstretched.

Hughes asks why the police car’s lights are on, and Milano says, “I need to control the situation.” Hughes asks, “What is the situation?”

Milano finally, at 1:54:48 a.m. — almost three minutes since Milano first ordered them back in the car — offers a reason, saying, “He was speeding, OK?”

Hughes asks several times what Dimmitt’s speed had been, and Milano says to Hughes, “You’re a passenger; it doesn’t matter.”

Dimmitt again tells Hughes to stop talking, and Milano orders Hughes to get back in the car. Hughes refuses, hands on head, saying, “I’m going to stand right here.”

Milano says, “We’re just gonna stand here till my backup comes.”

Hughes says, “I know you’re just trying to do your job.”

Milano says, “Then why you gotta give me a tough time?”

Hughes denies doing so. Milano adds, “I don’t need five people surrounding me, OK?” (In fact, there are three young men out of the car, and two young women inside the car. All three young men are near their own car and in front of the police car. The women do not get out of the car until later, when asked to by Milano and his backup. Milano is never at any point surrounded.)

Hughes corrects him: “There are three guys right here, and we are not threatening you.”

Dimmitt adds, “At all.”

Milano says “I don’t know you,” as if to say that he doesn’t know what to expect from them.

Hughes yells back, “I don’t know you either.”

Dimmitt tries again to calm down Hughes, saying, with a shrug, “I didn’t do anything wrong! It’s no big deal.”

The encounter continues in this vein, with commands and refusals, until Milano’s backup, Sergeant Philip White, arrives, four-and-a-half minutes after the encounter begins.

At that point, Milano yells, “Get down on the ground, or I’m going to tase you” and, about half a second later, tases Dimmitt. (In between the command and the refusal, Dimmitt says “No!” quietly but indignantly, so it is clear that he was not going to comply, although he also was not given any time to comply.)

Police view with civil liberties counterpoint

Asked why Milano started out at a high pitch of intensity and took such a long time to answer Dimmitt’s and Hughes’s questions about why he was there, Chief Deputy Monteleone supplied a possible reason — that Milano believed Dimmit was trying to evade him.

He said, by phone, “Having not been there myself, I don’t feel that I can second-guess exactly how he explained what he explained to the operator and those passengers. I believe, based on the information that we received from him, that, as he passed that vehicle and turned on it, the vehicle that they were in, seemed to be taking measures to avoid being stopped.

“And I think he probably was under that assumption at the time that he did make the stop, based upon the quick up the road — I’m not sure if they stopped for the stop sign at the end of that road or if they didn’t — and then quickly down, jog in next to the house, and then the car’s kind of parked not just in the driveway in front of the house, it’s in alongside of the house, so as to be kind of out of sight of the roadway.

“If you drove down the road you probably wouldn’t see that car, based on the way they positioned it. So I think his sense of what was going on there was probably keyed up, higher than it would be if it was a simple traffic stop that had no other extenuating circumstances. But obviously he was concerned, very early on in the stop, that there was something out of the ordinary and that he had reason to be concerned.”

The Enterprise asked Sara Dimmitt, who wrote a letter to the Enterprise editor criticizing Milano, if her brother had seen the police car and was trying to evade it, and she answered, “He pulled into the driveway of his home, and I can't think of a worse way to evade a sheriff, if that's what someone is trying to do. So no, he wasn't trying to evade him.”

Melanie Trimble, executive director of the New York Civil Liberties Union’s Capital Region chapter, had this view of Milano’s intensity: “Well here’s the deal. You don’t know what happened on the side of the cops. And they’re going to probably say that they had gotten a call that a bank had been robbed, and that the car fit the description or whatever … If there indeed was an emergency, then you can understand the police officer’s behavior. If there was no emergency, then that type of thing ought to be explained and investigated by the Sheriff’s Office.”

Asked his opinion of the encounter overall, Monteleone said, “Well, I can say that I was able to see the initial traffic stop, or the attempt at a traffic stop. I was able to see that, upon being stopped, the occupants of the vehicle exited without having been asked to do so, and then refused to sit back in their vehicle after being ordered repeatedly to do so. So I feel that they were ultimately charged accordingly, based upon their own actions.”

Asked if he thought Milano might have responded differently if the driver had been alone, Monteleone said, “I think it would have been less of a risk for the officer conducting the stop, if he had one, a sole operator, getting out. He could focus his attention strictly on that operator, and it would probably not have been as scary for the officer conducting the stop, certainly, because he wouldn’t have to divide his attention on driver, passenger, the third passenger that got out was behind the front seat passenger, and ultimately we could see that he was using a cell phone to record, but, given the darkness, the rain, and all the things going on, having a third person pointing something at you from behind somebody else, it was scary stuff. Absolutely was.”

Monteleone also indicated that he, watching the dashcam video, was mystified as to why Dimmitt kept repeating that he was at his home. “It didn’t appear that the driver (thought he) needed to comply,” he said, “no matter what the reason was, due to the fact that he felt he was ‘home,’ or had gotten home. It was like a ‘home base’ type of thing.”

The Enterprise asked Monteleone if Milano had had an obligation to announce that he was there on a traffic stop. “In a normal traffic stop, it is standard for the officer to advise the driver why they were stopped. You’re not just there to write somebody a ticket; you’re also there to possibly educate them as to why they were stopped.

“Sometimes people have no idea why they were stopped. Going a little bit over the speed limit, or they may have a headlight out, so yes, we, as a general rule, will advise the operator, ‘Look, the reason why I stopped you, sir, ma’am, was because of this: Your speed was this, or you didn’t stop at the stop sign, or your headlight or taillight is out, or your inspection sticker appears to be expired.’ And that way the operator knows right off the bat, ‘OK.’ And though the operator might not always agree with the reason that they’re given, at least they understand why they are being detained or pulled over.”

Monteleone then contrasted the “normal traffic stop” with this incident. In this case, he said, the officer didn’t have a chance to engage in a normal discussion that he would usually have with a driver who was seated in the car. “We have two people challenge him by getting out and then refusing to re-enter and sit in the vehicle; now we have a whole different situation,” he said.

Initially, according to Monteleone, “You had at worst — other than the fact that the driver was intoxicated — you would have possibly a vehicle traffic violation, which might or might not have resulted in a uniform traffic ticket being issued. When you escalate that by failing to comply, resisting or flatly refusing instructions that you’re given, you’re raising the situation from a normal routine traffic violation to potentially a criminal matter, and that’s where things change up.”

Trimble was asked if police are supposed to tell you the reason for a stop. She said, “Well, it depends upon the level of danger that they’re facing. If they are in pursuit of some guy that’s just killed a couple of people, and they think it’s you, the energy is there. They’re going to be jumping out of the car. They aren’t going to want you to ask any questions. They want you down on the ground, on your face, you know? They have a right to do that, as police officers. However, if there’s no emergency, and they’re simply pulling you over, and you’re asking why, then they should understand that this is not an escalated situation, and they need to behave appropriately.”

Trimble continued, “Police officers are supposedly trained to handle very difficult and tension-filled situations. And, if they can’t even handle the fact that somebody’s getting out of the car saying, ‘Why the hell did you stop me,’ that’s a real problem. Police officers should be able to handle such a minor question.”

Monteleone was asked if tasing was appropriate in this case, when Dimmitt was refusing to comply but not resisting physically or aggressively; when both Dimmitt and Hughes had their hands up; when Milano’s backup had already arrived, which should presumably have made it easier to control the situation; and, finally, when Milano had still never even touched Dimmitt or physically tried to take him into custody.

Monteleone said, “He’s not required to physically wrestle with somebody prior to deploying the Taser; that’s how the Taser falls in the use-of-force continuum. So just because he doesn’t get into a shoving match with this guy, doesn’t preclude him from using a Taser if he feels, based on the circumstances, that the person is not compliant, has not been compliant, and doesn’t intend to comply.

“You have a 6-foot-plus individual, and the other individual, on the other side of the vehicle, was at least that size, or larger. They were bigger, younger people … (The officer) determined that the Taser was the safest way to get compliance from the driver and take him into custody.”

Trimble’s answer was different. She had not seen the video, but it was described for her in detail, with all of the threats about tasing and all of the refusals to comply. The question put to her was: Is simply disobeying an officer’s commands grounds for being tased, if a subject is not threatening the officer in any way, not approaching, not drawing a gun?

She said, “We believe that the conditions under which a police officer should be using a Taser is just short of where he would use a gun. Now, if somebody refuses to get to the ground, is he willing to kill that person? If the stop is not legitimate and there’s no cause.”

She added, “I dare say that, if there was no reason for the stop, and no suspicion in the inner workings of the sheriff’s department to stop these people, then this was an overreach by the police officer, and that person should not have been tased.”

She concluded, “The only way to deal with this behavior on the part of police officers, right now, is to file a complaint with the Albany Sheriff’s Department. Make sure that the incident is investigated, and the officer will be either re-trained, or suspended, or punished, if he’s not following procedure. I haven’t looked at the Sheriff’s Department’s procedures on Tasers. We will certainly be looking at that.”

She added that the Albany County Sheriff’s Office has always been “very responsive to complaints and making sure that their officers are behaving properly.”

Monteleone was asked how much training deputies receive in interpersonal communication and de-escalation. He said, “They’re trained in the academy in interpersonal communication skills. I don’t know the exact number of hours.”

And after that, on the job?

“There is in-service training that is usually on different topics every year. I don’t know exactly the number of hours that officers receive in that.”

The Enterprise asked Monteleone about the procedure for making a formal complaint. He said that the first step would be for the complainant to contact the department’s emergency communications center, which is open 24 hours a day, and advise the dispatcher that he would like to make a personnel complaint. The dispatcher, he said, would take the name and information and schedule an interview with the station commander or a unit commander at headquarters. The complainant would be interviewed and fill out paperwork documenting the complaint, which the sheriff’s office would then start to investigate.