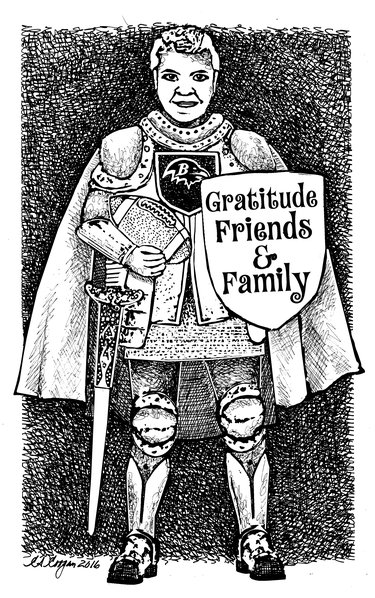

Portrait of a brave boy grown to manhood

Austin Carter was bullied in a public way this month — with an expletive-laced Facebook post in which a schoolmate threatened to shoot him. The effect was magnified with media coverage.

But Austin will not be cast in the role of a victim. He’s lived with autism all his life. Yet, he is not someone to pity. With the help of his family and his school, he has bravely embraced the world and its many challenges.

He agreed to talk to us about how the public bullying affected him. But we came away with a whole lot more. We came away with a reverence for the strong bond between Austin and his mother, Stephanie Carter. She wouldn’t believe it when, as a young parent, she was told her son would probably never learn to talk.

Austin talks now, with a low quiet voice. And he speaks words that show a wisdom beyond his 15 years.

Mostly, we were impressed by his honesty, his telling of truths even when they might not be flattering to himself.

In recording Austin’s story here, we hope our readers will see the brave young man that we do, and will also understand the supports that have shaped him — a friendly village cop, a caring teacher, a best friend, a loving family.

These are the threads of a tapestry too strong to unravel with the ugly words of harassment.

Austin starts by talking about one of his favorite things — sports. He likes to play basketball and football. He’s on the Unified team at Guilderland High School.

The basketball season has just ended and he earned a varsity letter. He’s proud of that.

“I like to play a lot,” he said. “I like it when I make baskets and I like to be able to pass the ball to my teammates.”

His Unified teammates have been important to him lately.

After the Facebook post was made public, after the classmate who harassed him was arrested, Austin’s teammates told him they have his back. That made him feel better. “One of my basketball buddies told me how angry he was.”

He remembers the anger and hurt he felt when he first saw the post. When he describes it, his usually calm voice has a catch in it.

Austin was upstairs in the bedroom in his Altamont home when he read the post on his phone. “When the text popped up on Facebook, it made me nervous and really upset,” he recalled.

He came downstairs and showed it to his mother and stepfather.

They had tried to get help when he was bullied before but to no avail. Recently, he and his best friend, Jay, had been playing football in Keenholts Park. The friends are inseparable in their free time — last summer they went to the Altamont Fair together every day the fair was open. Austin especially liked going on the rides, eating fried dough, watching the racing pigs, and feeding the tall giraffe in the circus tent.

The football they tossed around that day in Keenholts Park was brand new. Austin had saved up for it, starting with Christmas money, and earning the rest through household chores. He loves football — watching games every Sunday — and can recite names and positions of players past and present with uncanny accuracy.

His favorite player is Ray Lewis, number 52 for the Baltimore Ravens, now retired. “He was a great linebacker. He could sack quarterbacks,” said Austin of his favorite player. But, beyond that, “He had the energy to get the Ravens’ defense fired up.”

The two friends were tossing around the prized new football when other boys started mocking Austin. “They were laughing because of my voice,” he said.

“We tried to address that,” said Austin’s mother. “The school said it didn’t happen on school property so there was nothing they could do….The police said there was nothing against the law.”

The football, which had been thrown in the bushes, has never been found although Austin and his parents have searched for it.

After he saw the threat posted on Facebook, Austin stayed home from school. Austin had always liked school. His favorite subjects are social studies and math. He’s proud of being able to do multiplication and division in his head — no calculator needed. And the reason he likes social studies, he said, is, “I like learning about the whole world and what goes on.”

“The next week, it was better for me to go to school,” he said. That’s because, after the arrest, Austin’s tormentor was told he had to stay away from Austin. “The plan is the police said, he can’t talk to me, look at me, or text me.”

Austin is grateful to the police. He sees them as protectors and wants to be like them. He has wanted to be a police officer since he was little. As a boy, he was befriended by Patrick Thomas, an Altamont officer. “He would protect our community around Altamont,” said Austin. “He knows what’s going on. When I was a little kid, I met him and he proved how nice he was.”

“I think it would be hard,” Austin said of being a policeman. “But it would be a good job for me.”

When he was younger, Austin was afraid to speak up if he saw others being hurt.

Austin said he had witnessed others being bullied when he was in middle school. He speaks with utter honesty. “I just walked away from it and ignored it,” he recalled. “I was scared…I got nervous, if I stood up for someone, I would get bullied more.”

Not everything in middle school was bad. His all-time favorite teacher, Colleen Ryan, was at Farnsworth Middle School. Austin nominated her for Teacher of the Week, an honor she won, Stephanie Carter said.

“She always has a smile on her face,” said Austin. “She’s always been kind and made me focus on work at school. She’s proud of me when I tell the truth and am honest.”

With his name in the news, Austin has decided he can make a difference.

Since he’s been through the excruciating pain of being threatened so harshly and felt the warmth of support from his friends and family, Austin said, “I want to help people because it’s the right thing to do. It’s important so less and less people get bullied.”

“He wants to be strong and get past this and move on,” his mother said.

“It’s the right thing to do,” Austin repeated.

“I don’t want anything about Austin to change, because he didn’t do anything wrong,” said his mother. His schedule at school shouldn’t be changed to avoid the bully, and he shouldn’t have an escort at school, she said.

“He has worked so hard to be independent at school, to navigate on his own,” she said. “Let the bully have an escort. Change his schedule.”

As Stephanie Carter spoke, we were reminded of Golda Meir, Israel’s prime minister a half-century ago. When Israel was considering a curfew on women to help end a series of rape, Meir argued that it was the men attacking the women; if there were to be a curfew, it’s the men who should be forced to stay home.

We’re convinced that Stephanie Carter’s stance is part of the reason Austin doesn’t see himself as a victim. She’s also teaching him about continuing to care for others even when they have caused you pain.

Although she feels anger at the boy who bullied her son, Carter said, “Kids that do the bullying, something is missing in their lives. I hope he gets the help he needs.”

As our interview comes to an end, we ask Austin if we’ve missed anything important. Ah, yes, we have — gratitude.

“I want to thank all my family and friends who helped me through his,” Austin says.

His little sister, Madison, pats him on his shoulder as he talks.

— Melissa Hale-Spencer