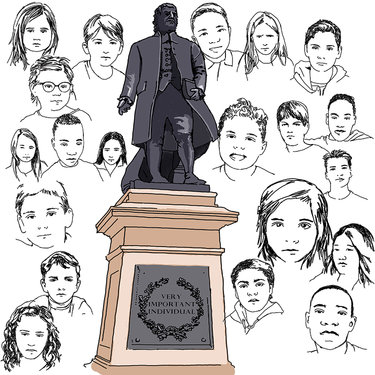

Protect all children as your own

Last month, I stripped the worn finish on an old drop-leaf table that had served as my desk in what had been the newsroom at 123 Maple Avenue in Altamont.

A century ago, Howard Ogbury had lived there.

He was the fifth and youngest child of John D. Ogsbury and, after becoming a junior partner in 1920, had taken over The Altamont Enterprise, serving as its editor and publisher, when his father died in 1943.

Since Howard was born in 1895, I figured he must have been nearly 50 then.

He worked at the paper, living over the presses until he died in his apartment in 1977. I know very little about him.

As I worked applying three coats of a hand-rubbed finish to his table, I imagined him eating there or maybe doing some late-night editing there in the days before editing was done on computers.

We are trying to preserve pieces of the newspaper’s history as we work in the building that has been its home for more than a century.

For a short while, I smiled when I saw the shine on the old table put to new use.

But then I got a phone call that shook me to the core.

A man, now in his eighties, who had worked at The Enterprise when he was a boy called from another state where he has lived for decades.

He grew up on a farm on the outskirts of Altamont and drove a tractor there when he was only 11.

At The Enterprise, he earned a dollar an hour, he said. It was the 1950s so that dollar had the purchasing power of 10 today.

The boy worked in the cellar where the old press still is today, unused. He melted down the lead type that had been formed into letters to print the paper.

“Howard would be at the Linotype,” he said of the machine that forms the letters of lead.

He’d say, “Give me a kiss.”

When the boy did, it led to other things, he said.

“Anybody who worked there had to know Howard did these things. He came on to every boy … He would bring you to his apartment upstairs and do crazy things.”

The man said it was “hard to explain” how he felt as a boy. “At that time, you’re coming into puberty … There was some pleasure and some guilt.”

He never told anyone. No one talked about those things then, he said.

Asked if he couldn’t tell even his parents, he said, “If I had, my Dad probably would have shot him.”

He also said, “I was ashamed to tell.” He thought it was something that he shouldn’t have done. “I should have run away,” he said.

Although he got married at 17, he said he later divorced. “It was my fault,” he said of the divorce.

Asked if the divorce had to do with what he experienced as a boy, he said, “It did. It did. It did … It’s due to what happened in Altamont, New York.”

Fifteen years ago, as he and his brother were talking about The Altamont Enterprise, he learned his brother experienced the same thing with Ogsbury when he, too, was a boy working at The Enterprise.

But they hadn’t known it until they were both old men. His brother has since died.

Few people are alive from that era to confirm the man’s account but it has the ring of truth.

This reminded me of other stories I’ve written over the years on the sexual abuse of children.

I wrote several years ago about a 1974 Guilderland graduate who claimed she was sexually abused as a sixth-grader by her teacher, Roderick Buckley. She told us it made her lose her trust in teachers.

When she was middle-aged, she was sitting around her sister’s pool with some friends when talk of Buckley came up. She learned that her sister, who is seven years older than she, as well as another friend at the gathering had suffered the same thing she had from Buckley as a sixth-grader at Fort Hunter Elementary School, she said.

“Oh, my gosh,” the alumna said, recalling her reaction upon learning she had not suffered alone as she’d thought.

“He would call us up to his desk at the front of the room,” she said, describing a big, gray metal desk. “All the girls wore dresses then. He would rub the back of your legs and up your bottom,” she said.

After we posted that story, Leo Muzzy, who was two years ahead of the alumna, called from Oregon to say he had seen, as a Fort Hunter student, the sort of abuse she described.

“I’m a witness who tried to do something to stop it,” said Muzzy.

He said he first heard about Buckley’s behavior as an 8-year-old when older boys were laughing about it in the boys’ bathroom saying, “Mr. Buckley feels up the girls.”

After Muzzy saw one of the targeted girls sobbing in Buckley’s class, he went to the principal’s office; he told Muzzy the girls should come forward, Muzzy recalled.

The girls did not want to come forward, Muzzy said, and he got in trouble for broaching the matter.

Figures in power, like a publisher who is an employer or a teacher and principal have a responsibility to protect the children in their care.

And the rest of us have to do what Muzzy did as a child: Tell when we see abuse to have it at least investigated.

We hope we have clawed our way into an era, with brave survivors speaking out about the crimes that wrenched them as children, where we adults are more mindful of children’s safety and our duty to protect it.

Why am I writing this?

Because it’s something we need to be willing to talk about, and our children need to be willing to talk about.

And maybe, as Muzzy did, another reader will come forward, making the man who suffered as a boy feel less alone.

I have spent a lifetime trying to seek the truth, even when it is difficult to acknowledge.

I have written on this page that the Catholic Church should let the victims of sex abuse tell their stories. We should do the same.

I like to think of our newspaper as a source for good, giving readers the information they need to keep our democracy strong, helping people to understand one another, bringing the community together.

If our own history at The Enterprise had a man at the helm who abused his position, that needs to be acknowledged.

We hope printing these words brings our caller some peace.

— Melissa Hale-Spencer, editor