The path to healing means allowing terrible truths to be told

We have followed Richard Tollner’s story with the Catholic Church for years now — and the latest chapter saddens and enrages us.

Tollner, who lives in Rensselaerville, worked without pay for more than a dozen years to help make the Child Victims Act into law in New York State.

We called for the passage of that act on this page and celebrated here when it became law, extending the statute of limitations for civil suits alleging sexual abuse.

Tollner had profound personal reasons for fighting for a chance for himself and others to have their day in court.

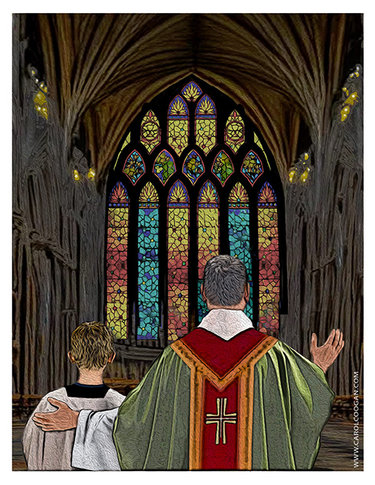

He told us how, when he was at the tender age of 15 and 16, he was sexually molested by a priest he had trusted at the seminary he attended.

“It affected who I was; it affected my confidence; it affected my opinion of people. It affected my sexuality. I wasn’t sure — was this my problem?” he told us.

When Tollner was 17, his father died in a car crash. He realized then that he had to take care of himself, he said, and soon after reported the abuse three times — to another priest, to a teacher, to the head of the seminary. Nothing happened.

This abuse occurred in the mid-1970s, before the Boston Globe’s 2002 exposé on priests abusing children, before such matters were openly discussed.

Tollner says he came to realize, “I’m not the bad guy. I never was the bad guy.” But that journey for him was long and painful.

Here’s how Tollner described it: “With children, it’s not like an attack. It’s more like grooming that child for a relationship so they do not realize due to the immaturity and the trust in the person.” Many sexually abused children feel guilty and even complicit.

“A lot of victims don’t even realize it was criminal until years, decades later when they realize, ‘Oh, my gosh, that was not only wrong but it was criminal,’” said Tollner.

At age 8 or 12 or 16, noted Tollner, “They haven’t developed their own sexuality.” And, as modern scientific research with scans has shown, adolescent brains aren’t fully developed either.

We repeated the sage advice Tollner shared: “If you know someone this happened to, or it’s yourself, tell someone you trust,” he said. “Tell a family member, tell a teacher, tell a parent, tell a policeman, tell someone because you’re not the only one … There are so many people out there that think, ‘This couldn’t be happening to anybody else.’”

But it is. In New York State alone, 40,000 children are sexually abused each year, and it’s a crime that is woefully underreported. According to the National Center for Victims of Crimes, one in five girls and one in 20 boys is a victim of child sexual abuse.

“Sex abuse is soul murder,” Tollner said. “It’s who we are, our essence, our personality, our character, our strength. Someone tried to take that from you. Take it back.”

So we were pleased that older New Yorkers would finally have a chance to regain some of what they had lost as children.

But then dioceses across the state began filing for bankruptcy. Albany’s last month was the fifth in New York to do so.

We read with deep interest this week the “letter to the faithful” Albany Bishop Edward B. Scharfenberger published in the most recent edition of the diocese’s publication, The Evangelist, and the pages of explanation that followed.

He described his decision to file for Chapter II bankruptcy as “difficult yet necessary.” He wrote that more than 400 lawsuits were filed by child victims between Aug. 15, 2019 and Aug. 14, 2021 and that the diocese had settled more than 50 cases.

“As a result of the Chapter II filling, the collection of debts and legal actions against the Diocese will stop,” the bishop writes, “allowing the Diocese to develop a reorganization plan that will determine the available assets along with the participation of its insurance carriers that can be used to negotiate reasonable settlements with Victim/Survivors in addition to other creditors.”

There are no “reasonable settlements.” This moral as well as financial bankruptcy makes that clear.

What these survivors needed was a justice system that let them find out long-hidden facts about their abuse, that let them tell their stories to a wider world than the Catholic Church, which is offering Masses of Hope and Healing.

As Tollner put it, their souls were murdered, and they needed a way to take back their essence, their character, their strength.

“We must reach out to all and journey with them through the healing process,” says the bishop, who also writes in his letter, “Christ Himself has shown us how difficult situations can lead to new life, that struggles can make us stronger, make us better.”

We see no accountability here. We do not see the church taking ownership of the crimes it committed.

In his Evangelist essay, “We’ll leave the light on” — referencing the church as “a safe place and refuge for all who seek consolation and support on their spiritual journey” — Scharfenberger cites the parable of the good Samaritan.

The parable, of course, tells of a man badly beaten by robbers and left to die on the side of the road. A Jewish priest and a Levite walk on by, but a Samaritan, a bitter enemy of the Jews, stops to help.

“If we seek to follow the gospels,” writes Scharfenberger, “then our first concern will always be how can we help, no matter who may have injured a person or how they came to that fate.”

What if a person was injured, not by random robbers but a known and trusted priest? Doesn’t the church that employed that priest have a particular responsibility to right that wrong? Isn’t that the path to healing both for the church and the victim?

“It’s a continuance of the diocese policy of not looking out for sexually-abused Catholic boys and girls,” Tollner told Noah Zweifel, our Hilltown reporter, soon after the bankruptcy was announced.

Tollner says that money was never the point, which makes the bankruptcy filing all the more cynical.

The first thing Tollner wants, he said, would be open testimony for all victims who want to speak. “As for compensation … there’s not enough money on the planet to compensate all the abuse victims out there for their pain and suffering.”

Speaking on the importance of testimony, as compared to settlement payouts, Tollner referenced the USA Gymnastics case in which nearly 200 women testified against the team’s physician, Larry Nassar, who was convicted on a variety of sexual crimes in the late 2010s.

“You can imagine that they got a form of justice, having the world know what happened,” Tollner said.

“Open testimony is education, education is power, power is prevention … That’s the first thing on the minds of most sex-abuse survivors, is not to let this happen to somebody else. That’s why we report it.”

Indeed, we had hoped, with the passage of the Child Victims Act, that testimony in abuse cases — not just against the Catholic Church, but against schools, and Scouts, and many others — would educate our society at large, making us all more vigilant in protecting children, as well as finally giving survivors the recognition they deserve.

Since the Albany Diocese has taken away that chance, a good start would be having the next edition of The Evangelist, rather than detailing the church’s view on the subject, publishing the stories of some of the survivors — in their own words as they see fit.

This won’t provide the process of discovery found in court nor the sense of justice provided by a society at large witnessing the abuse but it might partly counter the bishop’s sanctimonious view that this is “an extremely challenging time for our Church” as he urges the faithful “to pray for all involved that God’s peace and healing can prevail.”

We’ll close by repeating Tollner’s words: “Open testimony is education, education is power, power is prevention.”