We shall overcome someday

“This was on my bucket list,” said the woman walking next to me.

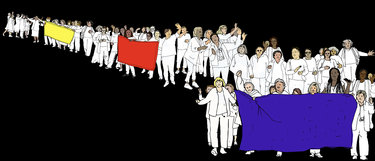

She wore white as did I, part of a long procession of women in white, stretching behind us as far as the eye could see.

The parade route was lined with more women in white, cheering us on.

This was Wellesley College on Sunday, May 25, 2025. I was marching with my class, the Class of 1975, at our 50th reunion.

Parades are a tradition spanning centuries around the world — from ancient Athens where Athena was honored with a procession to the Acropolis to the first procession in the United States, in Philadelphia on June 21, 1788, the day the Constitution was ratified.

The Wellesley alumnae parade is different from the parades we’ve recently covered in Altamont and Voorheesville and the Hilltowns. Like parades across our nation on Memorial Day, they bring a community together to honor those who fought and died in service of their country but also to celebrate our ongoing commitment to democracy and to one another.

Townsfolk line the parade route to cheer on our volunteer firefighters, our libraries, our youth groups, our elected leaders — all the many threads that weave the fabric of our communities.

What is different about the Wellesley parade is the people lining the parade route and cheering later become part of the parade, part of the procession of women’s history. The oldest alumnae go first — this year, from the class of 1950 — some of them chauffeured in antique cars, some of them still marching, all of them joyous.

As I marched last Sunday, I remembered standing on those sidelines as a young woman, watching the women in white at the head of the parade — women who were part of the first wave of feminism, women who had fought for suffrage, which became part of our Constitution in 1920.

Before I arrived on campus my first year at Wellesley, I was asked to read Virginia Woolf’s “A Room of One’s Own,” for a colloquium, which opened my eyes to feminism.

Woolf contrasts how men have written of women in fiction with how the patriarchy treats women in real life: “Imaginatively she is of the highest importance; practically she is completely insignificant. She pervades poetry from cover to cover; she is all but absent from history.”

This was an era, a half-century ago, when only 1 percent of federal judges were women, only 1 percent of engineers, 3 percent of lawyers, 7 percent of doctors, and 9 percent of scientists were women.

After my first year at Wellesley, I went home with the idea that I would liberate my mother. As it turns out, she liberated me that summer.

My mother nursed me back to health as I’d contracted mononucleosis during the end of the school year and then, together, we climbed the remaining Adirondack High Peaks I had not yet climbed to complete the 46 of 4,000 feet or more.

My mother knew the flowers and the ferns; she knew the animals by their scat and by their tracks; she knew the birds by their nests and by their songs.

Recalling that summer on my 50th birthday, my mother wrote, “We absolutely reveled when we met a father-son team who proudly said, ‘We’ve just climbed Skylight. Where have you hiked?’ We quietly boasted, ‘Oh, Cliff, Redfield, and Gray’ — and watched their surprised faces.”

What I learned that summer was each woman has to set her own course, to pursue what matters to her. For my mother, it was raising a family with love and gumption, cooking every meal from scratch, braiding rugs from our worn-out clothes, and later creating masterpieces on her loom to warm and inspire us.

Back at Wellesley, classics professor Mary Rosenthal Lefkowitz traced for us the two patterns for women in ancient myth: creative maidenhood or marriage-death. A popular movie at the time, “Love Story,” based on a novel by a classics professor at Yale, bore this out in a modern setting: The Radcliff heroine gave up her creative dreams to study music in Paris, instead marrying and supporting her boyfriend — and dying.

At last week’s reunion, over lunch, a classmate — now a lawyer in Colorado — recalled being poised, a half-century ago, to buy a T-shirt that said, “Women belong in the House and in the Senate.”

She said she was interrupted by a woman who angrily demanded, “What’s wrong with being a housewife?”

The path forward seemed clear to me: I wanted both to marry and to mother as well as to pursue my own creativity, my writing.

The Ivy League schools largely didn’t admit women and I was a student representative on a committee that considered having Wellesley become co-educational. I completed an ethnographic study on crew, tracing the history of what the sport meant to generations of women at the college.

I argued that, just as Virginia Woolf saw the need for a woman to have a room of her own to write and create, women needed a college of their own.

My class was at Wellesley during a time of great social upheaval. We lived in an oasis, walking verdant paths to classes in Gothic-looking buildings, listening to carillons sounding from a bell tower, cheering passing runners in the Boston Marathon that didn’t admit women till 1972, having afternoon tea poured by our house mother from a silver samovar.

But the world was out there for us to take on. I marched against fighting in Vietnam. I marched in Boston to “keep the buses rolling,” integrating schools.

I knocked on doors to promote passage of the Equal Rights Amendment, which, still, is not part of our Constitution. I have, still, on my wall a poster from the era centered with a 19th-Century engraving of jailed women.

It says, “Stone Walls do not a Prison make,/ Nor iron Bars a Jail,/ But ’til the ERA is Won,/ We’re only Out on Bail.” Right beside it is a poster, also from the era, silk-screened by a classmate, of a poetry reading I gave.

Wellesley was willing to push the limits and selected me as a candidate for a Rhodes Scholarship; the committee in Boston backed me and forwarded my name to the national committee, but the Rhodes trustees wouldn’t consider a female candidate. The next year, in 1976, thirteen women were among the 32 Rhodes Scholars.

What I felt in my bones last week as I toured my alma mater was that women have made great strides since I graduated 50 years ago.

The new graduate who greeted me at Tower Court where I stayed was an astrophysics major. She said she loved learning with women in the physics department and will leave campus for a job with NASA.

The new graduate who told visitors that climbed to the top of Galen Stone Tower to see the carillon be played explained how she uses all four limbs — both hands and both feet — to make the music that ripples over the campus. She had majored in chemistry at Wellesley and is headed for a Ph.D. program at CalTech.

These young women showed no doubt about the work they could do, the contributions they could make.

When Pauline and Henry Fowle Durant founded Wellesley 150 years ago, higher education for women was a radical idea. “Women can do the work,” said Mr. Durant. “I give them the chance.” He said he wanted to prepare women for “great conflicts, for vast reforms in social life.”

In this current era of great conflict, vast reforms are still needed.

As I marched last week with my sisters in white I felt joy to be part of something larger than myself. I felt joy to be marching with women of different races and religions, different sexual orientations, from different eras and from different places across the country and around the world.

I am proud to be part of the second wave of feminism. I will not be alive to cheer on the graduates 50 years hence but I know they will be doing worthwhile work to make the world a better place.

While progress is not easy or even steady — many women who started the suffrage movement were dead before the vote was won — we must keep marching forward.

— Melissa Hale-Spencer, editor