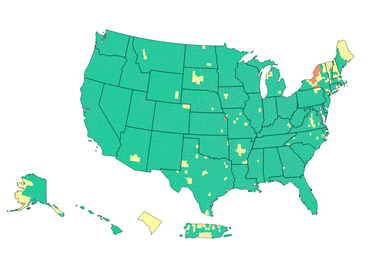

New York is the nation’s hotspot for COVID community levels

ALBANY COUNTY — As New York State is once again the epicenter of COVID-19 in the United States, Albany County this week has been designated by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention as having a “medium” community level of the virus.

On Saturday, April 16, the CDC map colored Albany County yellow, designating medium, for the first time since March 10.

Earlier this week, the state’s health department announced the first reported instances in the United States of significant community spread of two new subvariants of Omicron: BA.2.12 and BA.2.12.1.

The subvariants have been estimated to have a 23 percent to 27 percent growth advantage above the original BA.2 variant, which now accounts for 80.6 percent of COVID-19 infections in New York.

For the month of March, BA.2.12 and BA.2.12.1 rose to collectively comprise more than 70 percent prevalence in Central New York and more than 20 percent prevalence in the neighboring Finger Lakes region, the health department found. Data for April indicate that levels in Central New York are now above 90 percent.

The state, however, has implemented no rules for masks or other protocols to stem the spread of the virus. Governor Kathy Hochul lifted the mask-or-vax requirement for businesses in February, and the mask mandate for schools not in New York City was lifted on March 2.

When the CDC started the three-tiered system on Feb. 25, Albany County, like most of the nation, was colored yellow for “medium” or orange for “high” levels. On March 11, Albany County was colored green for a “low” level — no masks required — and had stayed that way until this week.

The designation is “determined by looking at hospital beds being used, hospital admissions, and the total number of new COVID-19 cases in an area,” the CDC says.

The advice from the CDC for a county, like Albany, labeled “medium” is three-fold:

— If you are at high risk for severe illness, talk to your healthcare provider about whether you need to wear a mask and take other precautions;

— Stay up to date with COVID-19 vaccines; and

— Get tested if you have symptoms.

The last two pieces of advice are given for counties labeled “low” and colored green.

Only in the counties labeled “high” and colored orange are people to wear masks indoors in public. The other advice remains the same.

Over 94 percent of the nation’s counties are labeled as being at a low community level by the CDC. Just 0.43 percent are labeled as “high” and all of those counties are in New York State, save for Wyandotte County in Kansas.

The New York counties labeled “high” include Broome, Tioga, Wayne, Seneca, Cayuga, Onondaga, Oswego, Jefferson, Lewis, and St. Lawrence.

Nationwide, 175 counties, or 5.43 percent, are labeled “medium,” including 18 in New York State: New York, Nassau, Westchester, Orange, Albany, Rensselaer, Essex, Clinton, Fulton, Herkimer, Oneida, Madison, Cortland, Tompkins, Schuyler, Yates, Ontario, and Monroe.

Based on the CDC’s original four-tiered system for community transmission — low, moderate, substantial, high — which is defined by cases per 100,000 of population, most of New York, like Albany County, is “high” (colored red) as is most of New England and also most of New Jersey.

High transmission is over 100 cases per 100,000; substantial is between 50 and 99, moderate is between 10 and 49, and low is fewer than 10 cases per 100,000.

Under the four-tiered system, in New York, only far-west Chautauqua County is labeled “moderate” while four counties — Schoharie, Wyoming, Allegany, and Cattaraugus — are labeled “substantial.” The rest are labeled as having high community transmission.

Mental health

Earlier this month, Thomas DiNapoli, the state’s comptroller, issued an audit showing that many school districts in New York lack sufficient staff for mental-health services.

“The upheaval caused by the COVID-19 pandemic created a crisis for many students in New York, but not enough is being done to make sure they are getting the information and support they need,” DiNapoli said in a statement, releasing the audit.

“The State Education Department should work with state and local entities to ensure resources to address the problem are available and prioritize mental health instruction and outreach among school districts so students and staff can recognize warning signs of distress and know how to get help,” he said, concluding, “I’m encouraged that the department responded positively to our recommendations.”

According to the American Psychological Association, over 80 percent of teens experienced more intense school-related stress due to COVID-19. The CDC reported that, in 2020, mental health emergency room visits rose 24 percent among 5- to 11-year-olds and 31 percent among 12- to 17-year-olds.

In December 2021, the United States Surgeon General issued a warning of an urgent mental health crisis among America’s youth.

DiNapoli’s audit shows that, among the three school districts covered by The Enterprise, rural Berne-Knox-Westerlo, with 752 students and three counselors, has the best ratio of counselors at 1:251.

However, BKW employs no social worker, the audit says, and has just one psychologist.

Voorheesville, a small suburban district, has 1,180 students and four counselors for a ratio of 1:295. The district also employs two psychologists for a ratio of 1:590, and one social worker.

Guilderland, a large suburban district with 4,841 students, has 13 counselors for a ratio of 1:372, eight social workers for a ratio of 1:605, and 11 psychologists for a ratio of 1:440 students.

Most of the state’s 686 districts outside of New York City, the audit says, entered the pandemic with mental-health teams that were far short of nationally recommended staff-to-student ratios:

— 19 school districts reported having no mental health professional staff at all;

— 653 (95 percent) did not meet the recommended ratio of one school social worker for every 250 students;

— 450 districts (66 percent) did not meet the recommended ratio of one school counselor for every 250 students; and

— 344 (50 percent) did not meet the recommended ratio of one school psychologist for every 500 students.

While state law does not require school districts to provide in-school mental health services to most students, the audit says, schools are often considered the natural and best setting for comprehensive prevention and early intervention services, and that the need for these services will likely increase as COVID-19–related and other life stresses continue to plague students.

DiNapoli’s office also audited mental-health education in schools statewide, surveying 22 districts.

New York was the first state requiring school districts to provide mental-health education. Given the urgency of the growing mental health crisis, State Education Department should ensure that school districts statewide have established a mental health curriculum and are using it, the audit says.

Currently, the department does not require districts to verify they’re meeting mandated mental health education standards, so it cannot be sure of what districts are, or are not, providing students, the audit says.

While all 22 surveyed districts were able to describe their mental-health curricula, only 19 provided supporting documentation to show they met the state’s minimum requirements. Three districts could not show evidence of providing mental health education in the midst of the ongoing crisis.

Auditors also found that the mental health curricula varied among the districts. The State Education Department, however, remained unaware of what any of these districts were, or were not, providing students in terms of mental-health education, the audit says.

With the stakes so high, the audit says, the department should act quickly to avert further crisis.

DiNapoli recommended State Education Department:

— Develop a mechanism to determine if school districts are providing mental health education as required by law; and

— Explore partnering with state and local entities to determine whether school districts should maintain certain staffing levels for mental health professionals.

In her response to the audit, Sharon Cates-Williams, deputy commissioner for the State Education Department, pointed out that “instruction designed to inform students about the importance of mental health as one of several dimensions of overall health and well-being is very different than the provision of mental health services.”

Mental-health services, she writes “are most often provided by a licensed mental health professional outside the school setting.”

As for mental-health education, Cates-Williams cites state law: “contents may be varied to meet the of particular school districts … and need not be uniform throughout the state.”

Responding to the audit’s first recommendation, she writes, “It is the responsibility of the members of the local board of education in conjunction with local school district administrators to develop and implement policies and practices that fulfill the statutory and regulatory requirements in a manner that meets the needs of the school community.”

The department, she says, “will explore the possibility of collecting an annual attestation from district administrators.”

On the audit’s second recommendation, Cates-Williams similarly responds, “ It is the responsibility of local school district officials and the local board of education to determine the staffing levels that meet the needs of the school community they serve.”

She goes on to cite a long list of entities the department confers with and states “the Board of Regents’ priorities include additional mental health supports for schools as evidenced by the Board’s budget and legislative request for additional funding to increase and improve Department capacity, as well as the capacity of districts to implement mental health supports in schools.”

Cates-Williams concludes, “To be responsive to this recommendation, the Department will continue the collaborative efforts with State and local entities and will persistently advocate for additional funds to support schools in these efforts.”