Gun control that everyone can agree on

This week, two of the schools we cover were disrupted by gun threats. Neither threat turned out to be substantive; no one was shot.

Nevertheless, learning was disrupted and students were no doubt scared.

At Voorheesville Middle School, someone wrote “I have a gun” on a bathroom stall, sending the school into hold-in-place mode, keeping students in their classrooms while police and their dogs scoured the corridors.

At Berne-Knox-Westerlo, a 15-year-old boy was arrested for terroristic threat, a felony, and aggravated harassment, a misdemeanor, after, police say, he told another student, “I am going to come to school with a gun and make sure I get you first and everyone else.”

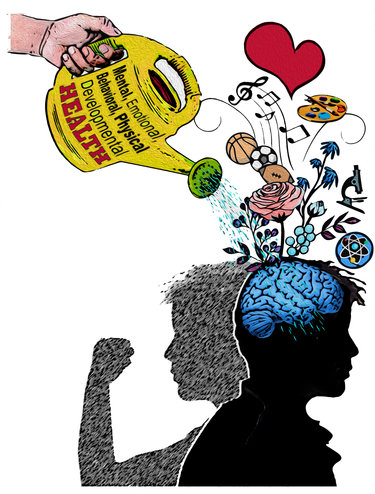

For decades on this page, often after our local districts reacted to the latest round of school violence nationwide, we have written of the importance of school funding and school focus being on the mental health of students.

“Our schools should be sanctuaries, not citadels,” was the title of our editorial in April 1999, the week of the school killings in Columbine High School in Littleton, Colorado.

We were heartened then when the Guilderland superintendent — as many districts rushed to beef up security, installing metal detectors and surveillance cameras and hiring armed officers — spoke to the school board and high school students of the need for “the development of a caring community, one in which we look after each other.”

Alluding to the fact that the two boys who caused the Columbine slaughter considered themselves outcasts, then-Superintendent Blaise Salerno said it was the right of every individual to demonstrate difference and to be accepted — and the school board backed him up.

After the 2012 shooting at Sandy Hook Elementary School in Newtown, Connecticut, we praised the New York State School Boards Association report, “Tending to Our Youth,” calling for access for students to mental health resources to prevent further shootings.

“We cannot and should not turn our schools into fortresses,” the report quoted from the December 2012 Connecticut School Shooting Position Statement, endorsed by more than 100 organizations representing over four million professionals, including teachers, principals, psychologists, social workers, and mental-health workers.

The position statement noted that hundreds of multiple casualty shootings occur in communities throughout the United States every year although few of them are in schools. “Children are safer in schools than in almost any other place, including, for some, their own homes,” it says.

When it comes to prevention, what matters is the motivation for the shooting, not the location. The statement went on, “…in every mass shooting we must consider two keys to prevention: (1) The presence of severe mental illness and/or (2) an intense interpersonal conflict that the person could not resolve or tolerate.

“Inclinations to intensify security in schools should be reconsidered,” said the professionals.

Rather, they wrote, “We believe that research supports a thoughtful approach to safer schools, guided by four key elements: Balance, Communication, Connectedness, and Support, along with strengthened attention to mental health needs in the community, structured threat assessment approaches, revised policies on youth exposure to violent media, and increased efforts to limit inappropriate access to guns and especially assault type weapons.”

At that time, we praised the current Guilderland Superintendent, Marie Wiles, who told us the week of the Sandy Hook massacre, “Building a culture where people look out for one another and care for one another — that’s what keeps us safe ….”

In 2016, we lauded state legislation requiring that mental health be part of the school curriculum. And we’ve since detailed and praised the many mental-health initiatives adopted by our local schools.

But stress caused by the ongoing pandemic has worsened an already dire situation. In December, the United States Surgeon General issued an advisory on “the urgent need to address the nation’s youth mental health crisis.”

“Mental health challenges in children, adolescents, and young adults are real and widespread,” said Surgeon General Vivek Murthy in issuing his advisory. “Even before the pandemic, an alarming number of young people struggled with feelings of helplessness, depression, and thoughts of suicide — and rates have increased over the past decade.”

He backed that up with data, reporting that, before the pandemic, up to one in five children ages 3 to 17 in the U.S. had a mental, emotional, developmental, or behavioral disorder. Suicidal behaviors among high school students also increased during the decade preceding COVID, with 19 percent seriously considering attempting suicide, Murthy reported.

Research covering 80,000 youth globally found that depressive and anxiety symptoms doubled during the pandemic, with 25 percent of youth experiencing depressive symptoms and 20 percent experiencing anxiety symptoms, according to the surgeon general’s report, “Protecting Your Mental Health.”

“Early clinical data are also concerning,” the report states. “In early 2021, emergency department visits in the United States for suspected suicide attempts were 51 percent higher for adolescent girls and 4 percent higher for adolescent boys compared to the same time period in early 2019.

“Moreover,” the report goes on, “pandemic-related measures reduced in-person interactions among children, friends, social supports, and professionals such as teachers, school counselors, pediatricians, and child welfare workers. This made it harder to recognize signs of child abuse, mental health concerns, and other challenges.”

Murthy’s report details important steps that young people can take, ranging from “ask for help” to “find ways to serve.” He has a long list of advice for families, too, ranging from being a good role model to looking out for warning signs.

The report also has detailed directives for educators, for health professionals, for journalists, for social-media companies, for community organizations, for foundations, for employers, and for governments.

We each have a role to play. We advise our readers to look at the surgeon general’s report and see what can be done by each of us.

Three Guilderland students, on Feb. 1, proposed a common-sense solution to one part of the problem: access to guns. They called for their school board to pass a resolution requiring education of parents on the secure storage of firearms.

“We are scared ….,” said Conor Webb. “We are demanding more because we deserve more.”

Webb is the president of the Guilderland chapter of March For Our Lives. The student-led organization with chapters across the country was founded in 2018 in the wake of the shooting at Marjory Stoneman Douglas High School in Parkland, Florida.

It would be wise for all of our school districts to adopt this resolution. Safety, like charity, begins at home. Most of the mass shootings in our nation don’t occur in schools so secure storage of guns would improve everyone’s safety, including that of youth themselves.

Over half of the nation’s suicides involve a firearm and most firearms deaths are by suicide, according to the U.S. Department of Justice.

“For a generation of children facing unprecedented pressures and stresses, day in and day out, change can’t come soon enough,” writes the surgeon general in his report.

It will take individual engagement, Murthy says, to overcome the stigma of seeking help for mental health issues.

“This is the moment to demand change — with our voices and with our actions,” he says.

What are we waiting for?