New Scotland condo project appears poised for approval

NEW SCOTLAND — As a three-year housing proposal appears headed for the finish line, talk recently turned to who would actually be living in the income-restricted condominiums.

The 50-unit project was first proposed as 72 apartments, which forced the town to make changes to its zoning law. The new town law allows only 40 total units in the hamlet.

But developers are eligible for a maximum 10-additional-unit density bonus “in return for providing certain amenities to the town,” like dedicating a percentage of total units to affordable housing; allowing public use of permanently preserved on-site open space; or meeting a number of energy-related provisions.

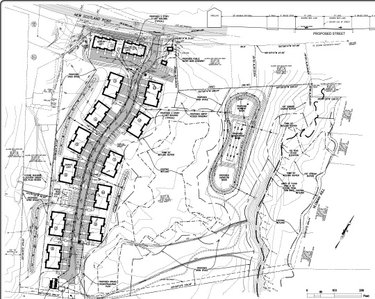

The current proposal is for 11 four-unit buildings and two three-unit structures. The land, at 2080 New Scotland Road, is owned by Richard Long, but the project applicant, Frank McCloskey, has been a partner at the project’s engineering firm, Hershberg & Hershberg.

If and when all approvals have been received, Pigliavento Builders will take over as the project’s owner.

During New Scotland’s April 3 planning board meeting, project attorney Andy Brick told board members that “timing is becoming critical,” noting the proposal is “coming up on three years” before the town. He asked if it would be possible “to wrap all this stuff up” at the next board meeting.

Chairman Jeffrey Baker told Brick, “I think it’s a go,” but the board still needed some of the landscape plans so it could sign off on the site plan. But Baker also noted that the applicant hadn’t submitted an evaluation “you know we were going to ask” about.

A large portion of the meeting revolved around the guidelines for who would be eligible to purchase the affordable-housing units.

Brick told the board the developer would sell six units to prospective buyers who made 88 percent ($99,440) of the New Scotland median income, which is about $113,000 using 2022 numbers. Another four units would be set aside for age-restricted buyers whose income was 96 percent ($108,480) of the town’s median income. The for-sale price of the affordable housing discussed during the meeting was $360,000 per unit.

“And those numbers are based upon where we are right now in terms of looking at construction costs, assuming a construction start within the next 12 months, current interest rates, tax rates,” Brick told the board. “So that is somewhat of a snapshot in time.”

But Brick also noted that “the town at some point in the future” would have “another bite at the apple for determining what these thresholds would be which would be in the form of the developer’s agreement that is negotiated with the town board.”

For example, Brick said, if, in a month or two, interest rates were to go down a point, the developer’s agreement could then say affordable units would be set aside for buyers who make 84 or 82 percent of the area median income.

“And the reason I think that may be a viable option to reach more people,” Brick said, “is interest rates are expected to go down.”

Baker responded, “Well, that's interesting; I hadn’t thought about putting it off to the developer’s agreement, and I’m not sure I agree about it, but when do you think the timing is on that would happen?”

Brick said, if the project were to receive conditional approval that night, which it didn’t, a developer’s agreement could be before the town board as early as its May meeting, but realistically, by June or July.

Affordability

Baker then turned the discussion to affordability, specifically the household wealth of prospective buyers of the affordable units, something Baker said Brick had left out of his presentation.

“It is certainly my understanding and belief that, when the town board set up the bonuses for density for affordable housing, they talked about the range of the median income,” Baker said. “It did not envision people necessarily who were downsizing and had a significant amount of home equity to put into [affordable housing].”

Baker said the town’s planning and zoning attorney, Crystal Peck, had researched the appropriate level of household wealth to take into account when determining eligibility, but Peck acknowledged that she had a difficult time finding guidance on situations like the one currently presented to the board, noting most guidance related to “truly low-income housing.”

Baker said of the research the board had received from Peck, “They look at household assets of about $100,000, [but] I’m not proposing a number that low because that’s a low level of income. I think we’re targeting here for the purchases of affordability.”

There was also discussion about how much a prospective affordable-condo buyer would have to pony up as a down payment. The proposal is for 10-percent down, but board members felt that might be too much for a buyer to come up with and thought 5 percent might work better.

Brick said at one point in the meeting that allowing buyers to put down 5 percent instead of 10 percent would “would drive the percentages up,” lowering the already-slim profit margin the developer is due to pocket on the project.

Baker, a semi-retired lawyer, said he’d heard that argument before on much larger projects and, if Brick wanted to make it, he’d need legal documentation proving it.

As the discussion wound down, it was decided that Peck and Brick would work out a framework for project affordability.