Health-care workers rally for state budget increases

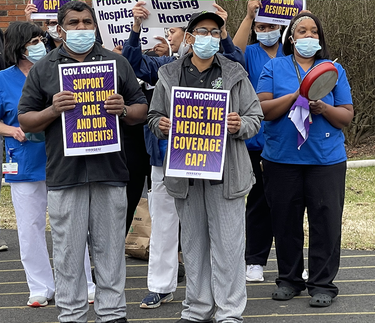

GUILDERLAND — Workers at Grand Rehabilitation and Nursing in Guilderland Center rallied during a recent lunch break to demand more state-budget funding for hospitals and nursing homes.

About two dozen members of 1199 Service Employees International Union took to the Guilderland facility’s parking lot on April 5 to call on Governor Kathy Hochul to close what they say is a Medicaid coverage gap in the 2024 state budget.

Mindy Berman, a spokeswoman for 1199 SEIU, said hospitals and nursing homes have received only a 1-percent increase in Medicaid payments over the past 15 years.

Of the protest, Berman said, “We are doing this with the employer and the legislators on our side.” A member of local Assemblywoman Patricia Fahy’s office was on hand to show support for workers, while Grand management spoke favorably to The Enterprise of the reimbursement-rate increase and what it would mean for its employees.

“The cost of living has risen, but yet the wages for the employees have not. I think it’s important for our employees to be funded and be able to live,” said Nyoki Tate, the Grand’s administrator. “The cost of living is consistently rising. Inflation is through the roof right now. And, if your salary [is] maintained the same, how are you going to survive in this, in today's economy?”

The union is looking to raise Medicaid — a joint federal-and-state-funded health-care plan for low-income and disabled residents — reimbursement rates by 10 percent for hospitals and 20 percent for nursing homes.

SEIU claims the governor’s proposed 5-percent Medicaid rate increase is “entirely offset” by changes to how the state pays for drugs that are part of a federal pricing program and also by cuts to a state program that provides funding assistance to hospitals “for the cost of care for low income individuals,” according to the program itself.

Overall, SEIU is looking to add $2.5 billion in health-care funding to next year’s state budget, which it says would, among other things, address an upstate-downstate disparity in reimbursement rates.

“So we have an issue here, where the government tried to pit upstate versus downstate,” Maurice Brown, the local political director for 1199 SEIU, told The Enterprise; the union claims upstate reimbursements are approximately 20-percent lower than downstate.

Refuting SEIU claims

But Bill Hammond of the right-leaning Empire Center argues SEIU is making “alarmist and inaccurate claims about Medicaid.”

Hammond in an April 6 blog post writes that New York State’s “Medicaid spending has grown by about 100 percent — or roughly doubled — over the past 15 years, including an increase of 28 percent or $20 billion since 2019.”

Hammond writes that the governor is proposing a 9-percent increase — not 5 percent as SEIU claims — to the state’s Medicaid contribution. SEIU, Hammond writes, is “cherry-picking an isolated cutback when total spending is going up.”

Hammond writes that New York State’s per capita “investment” in Medicaid is the highest among the 50 states, and 65 percent above the national average.

He also questions the union’s assertion that the Medicaid rate has only increased 1 percent over the past 15 years. Hammond writes, “This may refer to how the state sets the fees paid to providers, which are also called ‘rates.’ State law formerly called for them to be increased every year by an inflation-like ‘trend factor.’

“That policy was suspended during the Great Recession of 2008 and later abolished in 2011, meaning some provider fees were left unadjusted for years at a time.

“Still, they weren't frozen – or limited to 1 percent in 15 years.”

The 1-percent increase over 15 years is a muddled figure that has been repeated often by advocates of all stripes — from workers to management to lobbyists — but not even Hammond is entirely sure what it means.

“I mean, I’ve never actually heard anyone fully explain it to me to the point where I knew what they were talking about,” he told The Enterprise this week. “The state has a very complicated system for deciding how much it’s going to pay for any given service.”

Hammond said there’s a perception that New York’s Medicaid budget is constantly being cut, but he says that view depends on how you define cuts.

“A lot of times in Albany when they say they’re cutting something, what it means is they’re slowing the growth of it, they’re not increasing it as much as people would like,” he said. “Or they’ll cut in one place, but they;’ll increase in other places.”

The governor’s budget includes $35 billion for Medicaid — funding that has doubled since 2011, according to the proposal — with another $53 billion coming from the federal government, and $379 million additional dollars earmarked for the reimbursement-rate increase paid to hospitals, nursing homes, and assisted-living facilities.

The state used to automatically increase rates every year based on a trend factor, which former Governor Andrew Cuomo did away with, so now rates are adjusted in “other ways,” Hammond said.

Hammond said “the industry” will often pretend that rates have been flat, which isn’t the case — although an argument can be made that the increases have not kept up with expenses, he added. Which makes it “hard to fight back, because there is a kernel of truth to what they’re saying.”

The 1-percent talking point was invoked often over seven hours of testimony during a February budget hearing held by the state legislature on health and Medicaid-related matters.

Perhaps the clearest explanation of the 1-percent-over-15-years argument is an expansion of Hammond’s thoughts about the figure’s origin. It came in the form of written testimony from James Clyne, the president and chief executive officer of LeadingAge New York, an industry group representing not-for-profit nursing homes in the state.

Clyne writes, “Medicaid rates for nursing home care in New York are based on 2007 costs (discounted by 9 percent) and have not been updated or increased for inflation in over 15 years.”

Clyne writes that Medicaid rates “paid to nursing homes, assisted living programs (ALPs), and adult day health care (ADHC), for example, have not been increased for inflation in 15 years — a period in which costs have risen by more than 40 percent due to inflation alone.”

Clyne points to a specific culprit responsible for reimbursement woes faced by nursing homes and assisted-living facilities.

According to Clyne, the “elimination of inflation adjustments each year since 2008 means that by 2022 Medicaid operating rates are 41 percent lower than they otherwise would have been, despite annual cost increases experienced by providers.”

“These residents are suffering”

Lashonta Gordon has been a certified nurse assistant (CNA) for 22 years, the past four of which have been spent in her first union job at The Grand in Guilderland.

“These residents are suffering because we have no staff. We have no staff because nobody wants to work,” Gordon said. “Nobody wants to come here. They know we’re working short.”

The lack of workers has led to burnout, Gordon said, stating that she has to work extra hours to make up for the staffing shortage.

Ruthie Young, an organizer with 1199 SEIU, said “working short” has led to more worker compensation claims. “Our members are getting injured,” she said, “high numbers.”

“We have a census of about 68 members,” Young said. “When we should have 125 members.”

Data from Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) shows that all CNAs — in-house employees and contracted workers — at The Grand worked a median of about 184 hours for the three-month period between July and September of last year.

Grand CNAs worked a total of 16,493 hours during the period, while contracted CNAs accounted for 462.

For the third quarter of 2020, in-house CNAs worked a median of 166 hours and accounted for all but 12 of the 15,173 work hours in the period.

During the first three months of 2018, Grand CNAs worked 15,885 out of the 17,315 hours for the quarter.

Tate, the Grand’s administrator, said that having fewer in-house workers has led to the facility “utilizing [an] agency a lot more,” which increases employee costs significantly. Tate said using an outside employment agency “on average, maybe doubles what you would pay for each [in-house] staff member.”

Gordon said what “working short” really means is less time for residents. The Grand currently has 119 residents, according to Tate, with a capacity of 127.

Gordon said CNAs “are running around from patient to patient just doing the very basic.” Prior to the shortage, however, nursing assistants “had time to sit, to hold their hand, socialize.”

She said, “We don’t have the time to do that anymore.”

While Gordon doesn’t have a specific patient quota she has to hit each day, she said she has responsibility for between 12 to 14 residents in a typical eight-hour shift.

Gordon said her typical day includes feeding, bathing, and dressing residents, among other tasks. “And if we have the time, we’ll try to do nails and things like that, but there’s no time for stuff like that anymore.”

The CMS data shows the number of hours employees spend on “other activities” outside their normal work duties has dropped dramatically over the past five years, from 3,192 hours in the first quarter of 2018 to 1,443 hours between July and September 2020 to 579 in the third quarter of 2022.

Gordon said that, when she started as a CNA two decades ago, “we had lots of staff,” and even right before the pandemic started, staffing was “decent,” but once the pandemic hit, “that was it.”

Some residents don’t have families, she said, so the workers become their family. Workers are only meeting the residents’ basic needs, Gordon said. “You can’t spend 20 or 30 minutes with a resident like you used to four or five years ago.”