From the editor: Let a million sunflowers bloom

How do we know the world?

I spoke today to a man who was an early Peace Corps volunteer, sent to a remote village in Thailand. He was amazed by how little the villagers knew of the outside world. When he asked some of the children where they would like to visit, anywhere in the world, he was told only of a city a few hundred miles away. When he took a boy from the village there, to Bangkok, the boy didn’t understand how an airplane worked.

I felt like that boy last week when I saw a movie at the Spectrum 8 Theatre in Albany.

Because of the pandemic, I’d not been out to a movie in a very long time. But I desperately wanted to see this film, “The Guide” — not because it had been nominated for an Oscar as best foreign-language film, but because it was about Ukraine and more, because money from the ticket I bought would go to support the Ukraine Relief Fund.

Like the rest of America, I’ve been humbled by the horror of the Russian invasion of Ukraine and want to do something, anything, to help.

The film, directed by Oles Sanin, was made in 2014, the year that Russia took over Crimea. A new start was added for its current release with Sanin in a bunker, up against a brick wall, speaking of his love for Ukraine and the need for a no-fly zone.

The movie is set in the early 1930s as Stalin is systematically starving Ukraine. As I watched, I thought of how close we are to the 1930s.

In the United States, the Great Depression was part of the fabric of my family as I’m sure it was for many others. We grew up on the stories from our parents and grandparents. “Waste not, want not,” was my grandfather’s directive.

I realized, as I watched, that today’s Ukrainians had as part of their history, their intimate family history, their way of seeing the world, the gruesome scenes that were unfolding before my eyes.

The Ukrainians call the famine in 1932 and 1933 the Holodomor, stressing its man-made nature. It was between the two world wars — a time of peace — when millions of people in the Ukraine died, most of them ethnic Ukranians.

The film’s plot starts with an American communist, Michael Shamrock, an engineer fêted in a newsreel as a hero bringing tractors to Ukraine, who is to travel with his young son to Moscow. A widower, he plans to marry a singer who is also sought by a Soviet officer, evil incarnate, Comrade Vladimir.

Just before Shamrock is to leave for Moscow, a Ukrainian officer slips him material to deliver to British journalist Gareth Jones, exposing Stalin’s plans for Ukraine. Shamrock is murdered; as he lays dying, he urges is son, Peter, to run — and run the boy does.

Gareth Jones, I knew, was a real figure — the first journalist to report in the Western press on the Holodomor. He was murdered two years later.

“I walked along through villages and 12 collective farms,” Jones wrote in 1933. “Everywhere was the cry, ‘There is no bread. We are dying’ …. In the train, a Communist denied to me that there was a famine. I flung a crust of bread which I had been eating from my own supply into a spittoon. A peasant fellow-passenger fished it out and ravenously ate it. I threw an orange peel into the spittoon and the peasant again grabbed it and devoured it. The Communist subsided.”

Of course I recognized the importance of getting news to a wider world. And, as we can see currently in Russia, it is easy to keep the truth from people. Even in our own country, many people do not seek the truth.

Although I had thought of myself as being informed, what I realized, as the movie unfolded, was how little I know of Ukraine, how insular my world is, just like the boy in the Thai village.

The young boy in the movie becomes “the guide” for his foreign audience as much as he is the literal guide for the blind musician, the Kobzar, Ivan, who befriends him.

The scenes of the Ukraine countryside are breathtaking in their beauty just as the story is overwhelming in its sadness.

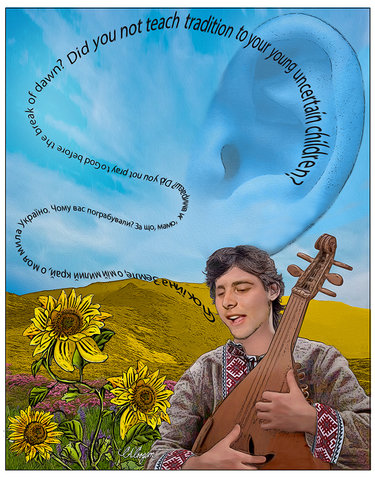

I had never before known of Kobzars; even the word was unfamiliar to me. They are wandering bards, most of them blind, who, over centuries, traveled Ukraine with their lute-like stringed instruments, kobzas, singing the history of their people.

I had studied traditional narratives for a doctoral degree. I knew of the Epic of Gilgamesh in ancient Mesopotamian mythology and I knew Njáls saga, the 13th-Century Icelandic legend. I certainly knew of Homer, the ancient Greek poet. I had read and been inspired by these words.

How is it I never had heard of Kobzars?

I spent any spare hours in the week since I saw “The Guide” looking up poems recorded from the Kobzars. An English translation from the Ukrainian, by Peter Fedynskyn, of one of Taras Shevchenko’s poems in “The Complete Kobzar” moved me to tears:

Placid Earth, O my dear land,

O my dear Ukraine.

Why have you been plundered?

What is it, mama, that you’re dying for?

Did you not pray to God

Before the break of dawn

Did you not teach tradition

To your young uncertain children?

How does any people learn its traditions? Often, it is from our families, from the stories we are told and repeat to the next generation.

Shevchenko was not just a poet, once freed from serfdom in the 19th Century, but also an artist who recorded folklore. He was convicted for writing poems in the Ukrainian language and for promoting Ukraine’s independence. In short, he was a hero — but I had not known of him.

In our modern world, we can learn of far-flung places, connected as we are with the internet — far from the narratives of bards. In my online searching, I came across a 2014 interview with Oles Sanin, director of “The Guide.”

Sanin said that, as a child, he met a Kobzar and briefly served as his guide while the old man sang songs on the street, at the market, outside the church.

“The Kobzars were the carriers of Ukranian oral history, language, tradition and culture,” said Sanin. “They were traveling minstrels who sang about freedom and fighting for independence … Stalin first destroyed Ukranian intellectuals, religion, middle class, finally the farmers in the Holodomor genocide of 1932-33.

“Stalin then targeted the Kobzars as a last stronghold of Ukrainian culture and national identity. Stalin outlawed their traditional songs of freedom, their instruments, tried to make them paid performers of Soviet propaganda. When everything failed, he decided simply to kill them.”

Some survivors kept the tradition alive, Sanin said, noting that almost all the blind Kobzars in his film are non-actors, playing traditional Kobzar music.

In Stanin’s film, there is a scene where a Kobzar is performing for a board of Russians, looking to record folk songs. They do not want to hear the lament of an oppressed people. They want him to play something livelier, more cheerful.

He obliges by performing a raucous, obscene ditty insulting the Russians — and is struck from the stage.

Such is the story the Ukranians tell themselves. Again and again in the film, which was wildly popular in Ukraine, stories like this are told or acted out. In one scene, as the Kobzar Ivan is being brutally tortured, he beckons his torturer closer and then urges him to kiss his ass.

In the end, the worth of the film isn’t in the plot — the dead American’s young son has clung to the papers his father was to transport to the journalist but they never meet their mark.

Rather, the film’s value lies in showing us a Ukrainian view of Ukraine’s culture, its history, and its identity — the deep well from which Ukranians draw their strength.

The sort of scenes Sanin recreated from the 1930s remind us of the clips we see today — like the Ukrainian woman walking up to the armed Russian soldiers occupying her town to give them sunflower seeds — Ukraine’s national flower. Weaponless, she tells them the Ukrainians don’t need liberating, that the soldiers are occupiers and enemies. She tells them to put the seeds in their pockets so, when they die, the sunflowers will grow.

— Melissa Hale-Spencer