In dealing with inmates, we need to think outside the box

We watched videos on Sunday of people literally dancing in the streets — in Albany in front of the Governor’s Mansion and in Manhattan in front of Andrew Cuomo’s offices. They were celebrating because both the State Assembly and the State Senate had passed, each with a supermajority vote, the HALT Act.

They were urging the governor to sign the act, and we are, too.

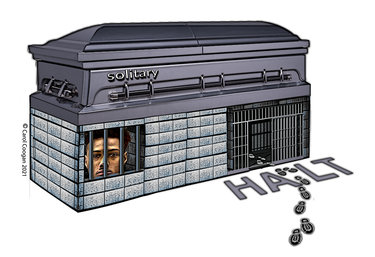

For decades on this page, we have called for an end to solitary confinement in jails and prisons. And we have supported the Humane Alternatives to Long-Term (HALT) Solitary Confinement Act from the moment it was drafted.

The HALT Act would ban solitary confinement for the young, the elderly, and the mentally ill; would cap the time in solitary in prisons and jails to 15 days; and would include more programming and out-of-cell time.

The era of racial reckoning that thundered upon us after the brutal death of George Floyd last May added impetus to this cause. So did the pandemic that killed a disproportionate number of people of color who were imprisoned.

While 18 percent of New Yorkers are Black, nearly half of the people in state prison are Black, and 57 percent of the people in solitary confinement are Black.

Governor Cuomo has said the HALT Act would cost the state and municipalities large amounts of money. However, Partnership for the Public Good, a community-based think tank in Buffalo, last year released an analysis that showed the HALT Act could save New York State and local governments an estimated $132 million dollars annually, or $1.3 billion dollars over 10 years.

The analysis showed an overall savings for the state of $114 million and for counties across the state a total of more than $18 million.

The greatest costs, though, are immeasurable. They are the costs of human suffering — suffering that goes beyond paying a debt to society and instead constitutes cruel and unusual punishment.

Solitary confinement can become a death sentence.

“Solitary confinement, even for just a few days, may significantly increase inmates’ risk of death after serving their sentences,” said a 2020 Cornell study. The research showed that 4.5 percent of former inmates who had spent time in solitary confinement — most for less than a week — died within five years of being released. That was 60 percent more than those who were not placed in solitary.

The study suggests that prison infractions should be handled with other sanctions — like fines, or loss of privileges, or a longer sentence — rather than solitary confinement.

A 2019 study, published in the Journal of the American Medical Association, found that inmates who spent time in solitary in North Carolina state prison “were significantly more likely to die of all causes in the first year after release than those who did not ... death by suicide and homicide in the first year and opioid overdose in the first 2 weeks after release were more common among those who had experienced restrictive housing compared with those who were incarcerated but never in restrictive housing.”

Inmates who spent more time in solitary were more likely to be reincarcerated or to die than those who spent 14 days or less in solitary confinement.

“Solitary confinement, which restricts people to minimal or rare meaningful contact with others, can cause such cruel and irreparable harm that the United Nations considers it torture to hold someone in solitary for more than 15 days,” says “Trapped Inside,” a 2019 report on solitary confinement by the New York Civil Liberties Union.

The report says that about 2,300 people are in Solitary Housing Units, or SHUs, across New York State and hundreds, potentially thousands, more are in Keeplock.

Prisoners under Keeplock sanctions, often in a general population cell, are still isolated for 23 hours a day but are usually allowed to keep their personal property and have greater access to basic benefits like phones and the prison store.

The average length of a SHU sanction is 105 days. Dozens of people have been in SHU for years, the reports says, some of whom have diagnosed mental-health disorders.

Unlike ordinary cells with gate-style doors, SHU cells typically have solid doors with only a small vision panel that can be closed by staff, making it extremely difficult to communicate with anyone outside of the cell.

Eight years ago, the United Nations called on the United States to end this form of torture.

New York State has a chance to do that now.

A mind-opening conversation that has stayed with us for two years is one we had in 2019 with Damion Coppedge, a Black man in his early 40s who was released from prison after 22 years. He had spent time in “the box.”

“This was designed to break a person down … in subtle and overt ways,” Coppedge told us, giving an example of corrections officers withholding food if “they didn’t like the way you look, the way you smell.”

Coppedge went on, “I struggled against the odds to not be insane … You either disintegrate or redefine yourself.”

Coppedge chose the latter.

He used his mind to escape his cell, escape the prison walls. He became a Buddhist, which he sees as “a philosophy of life.” And he became a poet. He was inspired in prison by poems he heard on the radio and picked up his own pen, harkening back to his childhood love of words.

Coppedge also transcended his cell by playing chess and he continues to teach chess as he rebuilds his life.

It takes a rare person, like Damion Coppedge, to come out of an SHU sanction with his humanity intact. We believe the things that sustained Coppedge in prison — a session where he was first introduced to Buddhism, mail that allowed him to play chess, a radio through which he heard poetry — are what has made him a productive member of society now that he is out of prison.

The “alternative therapeutic and rehabilitative confinement options” outlined in the HALT Act are what is needed to move our society forward.

The harm done by the torture of solitary confinement spreads beyond just the survivors of “the box.”

They and their families pushed long and hard for this legislation.

One of the people who spoke at the Manhattan rally on Sunday was Akeem Browder, whose brother, Kalief, was 16 when he was arrested for allegedly stealing a backpack and taken to Rikers Island. His family couldn’t afford the $3,000 bail.

Kalief was held at Rikers, without a trial, from 2010 to 2013 — with most of his days in solitary confinement. Two years after his release, he hanged himself.

Akeem Browder told the crowd in Manhattan on Sunday that the passage of the HALT Act came too late for his mother, who has died — “God rest her soul!” called out a man in the crowd — and too late for Kalief.

“But it’s not too late for people like my son here,” he said to cheers.

Akeem Browder concluded by addressing the governor directly: “You will pass this bill or it will get passed without you,” he said.

We still believe that our society will be stronger if inmates come out of jail ready to build a new life rather than returning to crime and prison. As a society, we’ll be saving more than taxpayers’ money; we’ll be saving our soul.