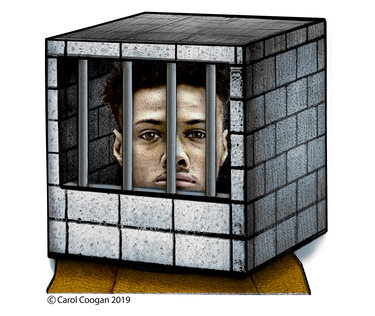

The UN calls it torture. NYS jails call it Special Housing.

Damion Coppedge says he feels remorse every day for the crime he committed as a young man. He’s 43 now and was released in July after 22 years in prison.

“When I was younger I was living without good in my life and I killed my best friend by playing with a loaded gun which went off and hit him and took his life. Every day I wish I could bring him back.”

Coppedge spent time in prison in an SHU‚ a Special Housing Unit — “the Box” — the most severe form of solitary confinement.

“This was designed to break a person down … in subtle and overt ways,” Coppedge told us, giving an example of corrections officers withholding food if “they didn’t like the way you look, the way you smell.”

Coppedge went on, “I struggled against the odds to not be insane … You either disintegrate or redefine yourself.”

Coppedge chose the latter.

He used his mind to escape his cell, escape the prison walls. He became a Buddhist, which he sees as “a philosophy of life.” He also became a poet. He was inspired in prison by poems he heard on the radio and picked up his own pen, harkening back to his childhood love of words.

You can hear the power of his poetry with a poem that opens this week’s Enterprise podcast.

Coppedge also transcended his cell by playing chess. The late Peter Henner, a lawyer and activist from Clarksville who wrote a chess column for The Enterprise, played chess through the mail with Coppedge, and wrote about it. “Focus has demonstrated a thorough knowledge of the openings, imaginative and creative play, and a good fighting spirit,” wrote Henner of Coppedge.

Coppedge told us that his name Focus came from his youth when he was so focused on playing an outdoor game of chess that he had not noticed it was raining. He’s since made Focus into an acronym for: Follow One Course Until Successful.

Coppedge, while in prison, also corresponded with a young chess prodigy in Uganda, Phiona Mutesi, who lived in the slums of Katwe. Disney made a film, “Queen of Katwe,” about Phiona’s meteoric rise in the chess world, based on a book by Tim Crothers. Crothers writes in his book that Coppedge sent Phiona three chess books and $25, prompting her coach to open Phiona’s first bank account.

The words at the top of this editorial, where Coppedge describes the crime that got him convicted of manslaughter, come from a letter he wrote to Phiona, printed in Crothers’s book.

Coppedge realized Phiona had to struggle every day to find clean water and food to survive. When she asked him about becoming a champion, he responded, “Pursue your own championships.”

Coppedge is now living in a half-way house in the Bronx and has just completed a job-training program where he did maintenance work. He likes going to the library and surrounds himself with “positive people” as he seeks work and rebuilds his life.

Our talk with Coppedge coincided with a story we wrote last week on the settlement of a suit that four young men, transferred from jail on Rikers Island in New York City to Albany County’s jail while awaiting trial, had brought against officials in New York City and Albany County. The officials admitted no wrongdoing but agreed to pay a total of $980,000 to the four young men.

We had written on this page, after the suit was filed in December, an editorial titled “Damaging the mental health of prisoners will not make our society safer,” in which we focused on the United Nations report defining as “torture” solitary confinement of the young.

Two of the men who filed the suit were 19; the others were 22 and 24. We wrote then:

“While the nation and the state are headed in the right direction in banning the torture of solitary confinement for youth, there is a gaping hole — the practices of county jails.

"This was brought home to us in a suit filed late last month against Albany County by four young men, transferred from jail on Rikers Island in New York City to Albany County’s jail while awaiting trial. Their suit alleges that, upon their arrival in Albany County, they and other detainees are brutally assaulted and then forced to live in solitary confinement for months on end. The suit alleges the city is circumventing its ban by sending ‘undesirable’ detainees to Albany County.

“After an initial assault on arriving in Albany County, Rikers detainees, the suit claims, ‘spend their remaining time at the Albany County Jail in solitary confinement,’ each one in a cell that is typically 6 by 8 feet.

“‘They are in their cells by themselves for a minimum of 23 hours a day, with no meaningful social interaction, environmental stimulation, or human contact,’ the suit says; they are offered one hour of “recreation” by themselves in an indoor cage, which most decline ‘because the cage is functionally indistinguishable from their cells.’

“These, of course, are allegations, not proven truths. The case will have to go to trial for the truth to come out.

“But what this suit makes clear is that many counties in New York State have no ban on solitary confinement for youths.

“They should.”

But, of course, the suit did not go to trial; rather, it was settled.

In the course of covering the story, we filed a Freedom of Information Law request, based on accusations made in the suit, requesting any documents that define policies or instruct employees of the Albany County Correctional Facility on the following topics: Use of tasers; use of pepper spray; rectal insertions or rectal examinations; beatings by correctional officers; solitary confinement; or privacy for inmates’ phone conversations with lawyers.

“Please be aware that any information requested which is not included with this response is not included within any existing general order,” wrote Undersheriff Michael S. Monteleone to Albany County Clerk Bruce A. Hidley in answering the request.

While policies on the other topics were provided, and Albany County Sheriff’s Chief Deputy William Rice explained them to us, no policy on solitary confinement, also known as punitive segregation, was forthcoming.

Chief Deputy Rice said the reason the Albany County jail has no policy or procedures for solitary confinement is simple. “We don’t have solitary confinement,” he said.

That makes us wonder, then, why part of the settlement, which Albany County agreed to, binds Albany County to follow the Rules of the City of New York concerning punitive segregation for any Department of Corrections detainees housed at its jail, from Jan. 1, 2022 to Dec. 31, 2023.

If Albany County has no solitary confinement, why would it agree to follow the city’s rules on it?

A report released last week by the New York Civil Liberties Union discloses data it obtained through a settlement in Peoples v. Annucci, a lawsuit against the state’s Department of Corrections and Community Supervision that led to changes in solitary confinement.

In 2018, the report says, there were 40,000 solitary confinement sanctions in New York State prisons, which hold about 45,000 annually. A quarter of those were SHU sanctions, the most restrictive form of isolation, the kind that Coppedge endured.

The rest were keeplock sanctions, meant for less serious offenses, where inmates are locked in their cells 23 hours a day but can generally keep personal property, make calls to family, purchase snacks or hygiene items, and have a view through bars rather than a solid door with a small vision panel than can be closed by officers.

The report, “Trapped Inside,” notes that the United Nation considers it torture to hold someone in solitary confinement for more that 15 days yet states that New York prison officials have “relied heavily on solitary confiement as a tool to punish and control people who are incarcerated,” constructing more than 3,700 SHUs during the 1990s.

“Trapped Inside” reports that the average length of an SHU sanction is 105 days, but 2,600 people were held in SHU more than 90 days, and 131 had sanctions for a year or longer. In 2018, the report says, 32 percent of SHU sanctions and 36 percent of keeplock sanctions were given to people with mental-health challenges.

“Trapped Inside” makes a compelling case for state legislators to pass the Humane Alternatives to Solitary Confinement Act, known as HALT, which did not pass in the last legislative session.

We wholeheartedly support the HALT Act rather than the lesser measures proposed by the Department of Corrections and Community Supervision. The HALT Act would ban solitary confinement for the young, the elderly, and the menatally ill; would cap the time in solitary; and would include more programming and out-of-cell time.

It takes a rare person, like Damion Coppedge, to come out of an SHU sanction with his humanity in tact. It looks to us like the things that sustained Coppedge in prison — a session where he was first introduced to Buddhism, mail that allowed him to play chess, a radio through which he heard poetry — are what will make him a productive member of society now that he is out of prison.

“Trapped Inside” focuses on state prisons rather than county jails, which incarcerate people awaiting trial, arrested on parole violations, or convicted of a crime and sentenced for a year or less.

There is a lack of data on solitary confinement for jails, the report acknowledges, noting that jails operate according to regulations issued by the State Commission of Corrections, which has stated there has been a “prevalent misuse of solitary confinement” in jails across the state.

And so we reiterate our call from earlier this year. Our county jail should be transparent in letting the public know if it uses solitary confinement, the ages and mental conditions of those it confines, and for how long and how often.

We recently commended, on this page, Sheriff Craig Apple’s progressive plan to use a vacant portion of Albany County’s jail for homeless people and parolees who need a place to start their lives over. And we continue to commend the sheriff on programs he has instituted to help inmates who want to overcome addiction, and to help veterans who are trying to rebuild their lives.

We’ve also commended county leaders on this page for taking on issues ahead of state legislation that improves health and safety here in Albany County.

Regardless of whether state legislators adopt the HALT Act, as they should, legislators here in Albany County, working with a progressive sheriff, have a chance to act now to limit solitary confinement to the United Nations’ recommended 15 days and ban it altogether for vulnerable populations.

Our county will be stronger if inmates come out of jail ready to build a new life rather than returning to crime and prison. As a society, we’ll be saving more than taxpayers’ money; we’ll be saving our soul.