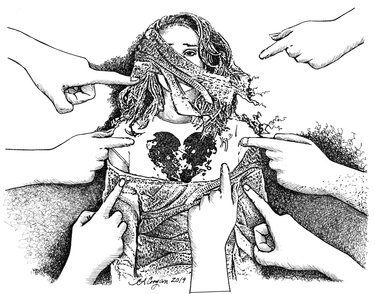

Ignoring child victims is easy, absorbing truth is hard

We knew we were missing an important part of the Tod Mell story. Last October, we had written about the arrest of this beloved long-time Lynnwood Elementary School teacher.

Mell had been charged with a misdemeanor, endangering the welfare of a child, after a complaint was filed on Oct. 4 in Guilderland Town Court, stating he engaged “in unlawful physical contact” with a female juvenile at Lynnwood Elementary School eight years earlier. Mell struck a deal, pleading guilty, at the same time the arrest was announced and the complaint was filed. No one — not the police, the district attorney’s office, Mell’s lawyer, or Mell himself — would tell us what precisely he was guilty of.

We frequently publish news of misdemeanor arrests for endangering the welfare of a child; typically the police arrest report will give an explanation — a child was left unattended in a car while a parent shopped, for example. No such explanation was forthcoming in the Mell case.

Mell was sentenced in Guilderland Town Court on Jan. 17 to two years of probation; he also had to surrender his teaching certificate and follow sex-offender conditions. Judge John Bailey would not read the victim’s impact statement aloud in court, saying, “If the victim’s not here, I’m not going to read it, because legally I don’t think I can.” He looked around but no one came forward.

Our Guilderland reporter, Elizabeth Floyd Mair, requested and received the more than 30 letters submitted to the court in support of Mell. Former students, parents, colleagues, friends, family, and school-board members wrote about what a fine teacher and person Mell is.

The thrust of many of these letters was that Mell had been wronged by an accuser.

This week, we have the rest of the story. The victim and her parents spoke at length with Floyd Mair. The story is difficult to read but we believe it is essential to tell.

The victim, who graduated from Guilderland High School last year, told Floyd Mair that, when she was in Mell’s fifth-grade class, he often put his arm around her and would slide his hand down to her vagina and rub it, on the outside of her clothes. He did this when they were alone and when other students were present, she said, with the view of where his hand was hidden behind his desk. He would keep his hand on her vagina until she walked away “awkwardly,” she said.

This experience has haunted her throughout her young life. A therapist has told her parents she suffers from post-traumatic stress disorder.

Her parents came to us because they felt the community response to Mell’s sentencing — one school board member, Tim Horan, called the “false accusation” a “travesty of justice” — was hurting their daughter, again.

It often takes years for traumatized victims of inappropriate physical contact or other kinds of sexual assault to come forward with allegations, and cases then are hard to prosecute. We’re pleased that New York State has just lifted the limit for children who suffered from sex crimes so that now, as adults, they may finally have their day in court.

School board members, like teachers, should be looking out for the welfare of children first. One long-time school board member, Judy Slack, who also worked as a teaching assistant at Lynnwood for two decades, wrote to Judge Bailey that she hoped he would allow Mell to avoid probation “and perhaps not give up his license so that he can resume making significant contributions to our community.”

Horan, a retired elementary school teacher as well as a current school board member, wrote that Mell is “the victim of a gross miscarriage of justice due in part to a rising tide of #MeToo McCarthyism that has swept the country.”

Mell’s lawyer also cited the #MeToo movement and stated Mell pleaded guilty in order to avoid the possible “consequences to his family if this were to continue,” which could have been “monstrous,” including Mell being put on a registry, being unable to get a job, and being unable to see his own children.

We believe what happened to Mell’s victim was “monstrous” and that Mell pleaded guilty because he was guilty, and two years of probation and giving up his teaching certification was a preferable alternative to going to prison and being put on a sex-offender registry.

We’ve seen similar reactions over the years in Guilderland schools where the first response after a teacher was accused of wrongdoing was for colleagues to defend that teacher.

In the 1980s, five girls in Bruce Sleeper’s fifth-grade class told their health teacher that Sleeper made them uncomfortable with things he did and said. The initial reaction was disbelief; Sleeper was a charismatic teacher who led popular wilderness camping trips. In 1989, he pleaded guilty to second-degree sodomy.

In 2003, colleagues were shocked and parents spoke in defense of John Wagner, a popular house principal at Farnsworth after district officials said Wagner had focused on the groin areas of fully-clothed male students while making school videotapes.

In 2003, when parents complained a junior-varsity girls’ volleyball coach at Guilderland High School, Deborah Hayes, had their children wear signs saying they were sluts, the school board voted, not to fire the untenured teacher but rather to extend her probation for a year; the only dissenting vote was cast by school board member Barbara Fraterrigo.

School leaders did not deny the allegations but rather extolled Hayes’s virtues as a creative and popular teacher who offered much of value to the school. It took the victims coming forward to tell their stories and show their pain for school board members to change their minds.

Carl and Laura Letson, herself a former school board member, sued the district, saying their daughter, Sarah, “was subjected to sexual harassment while a member of the junior varsity volleyball team.” The Letsons moved to Florida in 2003 because, they wrote in lengthy letters to the Enterprise editor, they wanted to avoid the apparent retaliation their daughter had suffered after complaining about Hayes.

Laura Letson wrote, “Our daughter, age 15, cannot comprehend why school district employees, administrators, and elected board officials have gone to the extent demonstrated to date to protect a teacher at a student’s expense and well being ....”

To have a vocal faction of the Guilderland school community now misconstrue Tod Mell’s sentencing as a miscarriage of justice is unfair to the victim.

“Victims of rape and sexual assault are all too often re-victimized and burdened with the narrative that their allegations are false ...,” says Kathryn Merrick, case manager with the Albany County Crime Victim and Sexual Violence Center. “Sadly, that victim-blaming and its effects fall squarely on the shoulders of the person who was harmed and only compound their already existing trauma. I have spoken with countless survivors who say that they felt as or more victimized and traumatized as a result of events flowing from them reporting their rape or sexual assault, than they did during the initial assault.”

Let us not, as a community, make it worse for the victim who was courageous enough to come forward. Let us not re-victimize her.

Shouldn’t school board members make a statement of apology for failing to protect the students under their care rather than construing the man who pleaded guilty as himself the “victim?”

Such attitudes only exacerbate the problem. Women rarely come forward to report sexual crimes. Using federal crime numbers, the Rape, Abuse & Incest National Network estimates that for every 1,000 rapes, 57 reports will lead to arrests, 11 will be referred to prosecutors, and just seven cases will lead to felony convictions.

The #MeToo movement is a long-overdue attempt to balance that ledger. The two examples that Horan cited in his letter to Judge Bailey — Tawana Brawley and the Duke lacrosse team — were of false accusations that fell apart under the scrutiny of the legal system. In 1988, after hearing evidence, a grand jury concluded Brawley had not been the victim of sexual assault and may herself have created the appearance of an attack. In 2007, the North Carolina attorney general dropped all charges against the three Duke lacrosse players and declared them innocent of rape allegations.

Those examples are not relevant to what happened in Guilderland where police investigated allegations and, as Cecilia Walsh, spokeswoman for the Albany County District Attorney’s Office, told us, “The police had probable cause to arrest him based on the reported conduct, and he pleaded guilty to performing the conduct.”

Judge Bailey was wise to hand down the sentence to which Mell, in pleading guilty, had agreed. It is sensible that his sentence would include sex-offender conditions and that he would lose his certification to teach. These are protective measures for the good of the society so that other children will be spared.

This week, we are publishing, in its entirety, the victim’s impact statement that was not read in court. We share Judge Bailey’s concern about protecting the victim’s identity but we believe her words need to be heard.

Perhaps other now-nearly-grown children will come forward with their own stories. Perhaps not.

At the least, the community at large will know what one person has suffered and will also appreciate her generous spirit.

In her statement, the victim directly addresses her former teacher, Tod Mell, a teacher who had made her feel special, saying, “I always had in the back of my head that the things going on weren’t ever supposed to happen to a student, but I really did trust you, which is why I was so blinded by what you were doing.”

She goes on, “The worst part is, when I thought about telling my parents or friends or anyone, I froze and I thought not about myself but your family … but I thought of what you could still be doing to girls in a school I realized that if I waited any longer it’s almost my fault for not saying anything.”

Having told her story to save other girls from a similar horror, the victim ends with hope that her one-time teacher will right himself: “... I really thought you were a good person and maybe one day you’ll change who you are and won’t touch a girl like that anymore because all I want is for you to never again make someone think so much less of themselves.”

Secrets fester. To heal — as an individual or a community — the truth must be told.