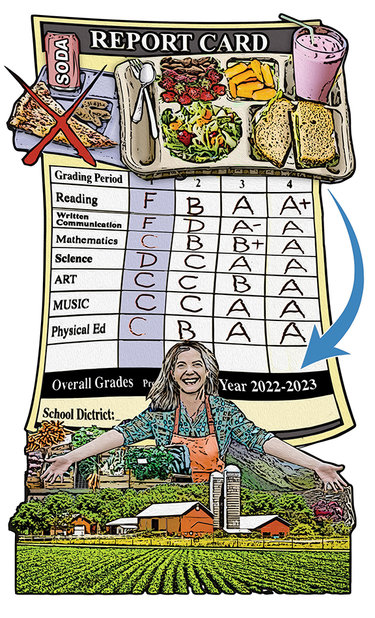

A bill that promises healthier school lunches with sides of improved local economy and environmental protection

You get what you pay for.

Put your money where your mouth is.

Adages, like these, endure because they speak truth.

Both adages apply to a bill proposed by Senator Michelle Hinchey, who chairs the Senate’s Agriculture Committee, and by Assembly Majority Leader Crystal Peoples-Stokes. The bill was trumpeted by Hinchey and its backers at a press event held at Indian Ladder Farms last Thursday.

If it became law, New York municipal institutions, like schools, hospitals, prisons, and child-care centers, would have more leeway in making food purchases.

The current procurement laws, Hinchey says, are a half-century old and don’t reflect modern values.

Now, municipal institutions, when contracting for food, must choose the lowest bidder. At first look, this makes sense and saves cents. Why should taxpayers have to pay a penny more for institutions to procure food?

But remember the adage: You get what you pay for.

Often the cheapest food isn’t the most nutritious. Nutritious food is good not just for the human body but the human brain.

Too often, we gravitate toward over-processed foods filled with sugars and fats — like the ever-popular school cafeteria entrées of pizza or macaroni and cheese.

However, a slew of scientific studies have shown that so-called “comfort foods” don’t really provide comfort at all. Rather, what the human body and brain need for both a sense of well being and mental fitness are leafy greens, colorful fruits and vegetables, beans and nuts.

Over the years, we’ve highlighted local school cooks who have gone to extra lengths to create nutritious meals from locally-sourced foods. We’ve written favorably on this page about the federal farm-to-school initiative that began in 1997, allowing local farmers to sell fresh fruits and vegetables to schools, benefiting the farmers, the schools, and the students.

We’ve also praised on this page local school districts developing wellness policies that, as in the Guilderland schools, were ahead of the federal government guidelines in serving healthy lunch foods and banning unhealthy vending machine snacks.

And we’ve supported the shift, under the Obama administration, for healthier school lunches.

It’s wise to feed kids healthy foods so they are well nourished and develop good eating habits to last them a lifetime. The epidemic of obesity in this country is, like the malnourishment of children, costly for society as a whole.

Obesity costs New York State over $12 billion annually in health-care expenses, according to the state’s comptroller. And it is a leading comorbidity with COVID-19.

Children who are malnourished can’t learn well; their brains don’t develop as they should; their futures can be troubled — costing society as a whole in the long run.

The federal government, in the midst of the pandemic, wisely extended its support for meals at school beyond just households that are income eligible.

The proposed Good Food Purchasing Bill would allow municipalities to award food contracts to businesses that are no more than 10 percent costlier than the lowest bidder if the bidder possesses one or more of seven qualities.

Nutrition is just one of the listed qualities but we would speculate that more nutritious food alone would end up, in the long run, costing New Yorkers less, taking into account the added health-care costs for obesity and the added resources needed to get undernourished people the help they then require.

That brings us to the second adage: Put your money where your mouth is.

Many politicians and citizens give lip service to the importance of environmental sustainability, racial equity, fair labor practices, boosting local economies, protecting animal welfare, and paying farmers fair prices; these are the other six qualifying qualities listed in the Good Food Purchasing Bill.

The bill would actually do something about achieving those ideals. Hinchey said that a broad coalition of 80 organizations is behind the bill, and a handful of their representatives were present at the Indian Ladder Farms event.

Public purchasers wield enormous power based solely on the money they routinely spend for food.

New York State currently has one of the most restrictive procurement laws in the nation, according to Ribka Getachew of Community Food Advocates. “That’s not hyperbole,” she said.

She noted that public agencies in New York City alone spend half-a-billion dollars annually on food so the new law would have enormous reach.

Although a few cities, like Los Angeles in 2012, have instituted good-food-purchasing protocols, this bill, if it passes, would make New York the first state to do so.

“Quite often, as New York moves, so does the nation,” said Anthony Gaddy, co-founder and president of the Upstate New York Black Chamber of Commerce. Gaddy said the legislation had the potential to transform the way New York State does business.

Laurie Ten Eyck of Indian Ladder Farms said of the legislation, “It encapsulates what farming is and how challenging it is and how many things we as farmers are expected to and need to do and want to do.”

Farmers, she said, need to feed every single person on the planet while preserving the environment, caring responsibly for animals, and paying fair wages — all while still making food affordable.

This bill would help farmers do that. Protecting the environment would be a benefit for each inhabitant of Earth.

Peter Ten Eyck, 83, Laurie’s father, said Indian Ladder Farms raises healthy food with the least amount of pesticide, adding, “The apples we grow are not all big and beautiful.”

Unlike large industrial farms in the Midwest, Hinchey noted many of New York’s farms, like Indian Ladder, are small and owned by families “who genuinely care about every being on their farm.”

Michael Laster, the principal at Guilderland’s middle school, said that not only would the bill “provide our families with high-quality, nutritious foods that are locally produced,” but it would strengthen the school’s relationship with farmers. He envisioned school field trips to farms, and farmers making classroom presentations to inspire students.

“New Yorkers want a more humane food system,” said Bill Ketzner with the not-for-profit American Society for the Prevention of Cruelty to Animals. “They want a system that’s compassionate to animals, to farmers, to consumers, to workers, and to the environment.”

A recent ASPCA survey showed that nine out of 10 Americans are concerned about the impacts of factory-style farming and more than 70 percent said they’re seeking out more local products or products that ensure higher welfare for animals.

There is very little oversight or transparency at the federal level to ensure treatment of the 10 billion chickens, pigs, cows, and turkeys raised for food in large facilities each year, he said.

“COVID-19 revealed just how fragile our industrial food chains really are, creating an urgent need to build more resilient regional food systems,” said Ketzer.

The pandemic also revealed how central municipal agencies are when it comes to feeding people.

Josh Kellerman, with the Retail, Wholesale and Department Store Union, said that often the lowest bidders push costs back onto communities.

“It’s not a zero-sum game,” said Kellerman. “Workers can lead dignified lives, doing the work they love, and business owners can thrive too.”

He also said, “Values-based contracting puts public dollars where our values are.” The bill would redistribute resources “to those who do right by our communities, workers, and the environment …. This bill disadvantages those whose only goal is greed.”

We believe most New Yorkers value the seven qualities listed in the bill. We know for sure New Yorkers value environmental protection because, on Nov. 2, voters strongly supported adding a sentence to the Bill of Rights in our state constitution: “Each person shall have a right to clean air and water, and a healthful environment.”

The Good Food Purchasing Bill is a way to let the free market do just that: make our environment more healthful. It’s a way to put our beliefs to work through the public institutions that we fund.

We strongly urge support of the bill, which will lead to healthier eating, a better protected environment, a more diverse workforce, and more resilient local economies and food systems.