For-profit nursing homes are likely to fail our elderly before they fail their investors

The focus since New York State Attorney General Letitia James issued a report last Thursday on nursing-home response to the pandemic has been largely on her findings that more nursing-home residents died of COVID-19 than data from the state’s health department had reflected.

Hours after James’s report was released, the state’s health commissioner, Howard Zucker, responded that, from March 1, 2020 to Jan. 19, 2021, there have been 9,786 confirmed fatalities associated with residents of skilled nursing facilities, including 5,957 fatalities within nursing facilities, and 3,829 within a hospital.

“This represents 28% of New York’s 34,742 confirmed fatalities — below the national average,” wrote Zucker, citing a national figure, from the Kaiser Family Foundation, of 35 percent of COVID-19 deaths being nursing-home fatalities.

Zucker’s newly released numbers show the deaths attributed to nursing home residents is 40 percent higher than counting just those residents who died in nursing homes.

Certainly, the state should have released those figures — the number of nursing-home residents who died in hospitals — earlier.

Accurate information can be a matter of life and death in the midst of a pandemic.

There should be a national system for reporting deaths and it should begin at the county level. Albany County, which has done a commendable job amassing data throughout the pandemic and sharing it with the public, has struggled for the last 10 months to keep on top of nursing home deaths here.

On Saturday, the county’s executive, Daniel McCoy, reported eight more deaths of county residents from COVID-19 — four of them since the day before but four of them from earlier in January.

Currently, nursing homes are required only to report deaths to the state, leaving the county out of the loop.

This makes no sense as it is up to county coronors to certify deaths. There should be a direct conduit from there to the state and national levels. This would take the politics and finger-pointing out of the equation.

Weekly, the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services, known as CMS, reports data on cases of COVID-19 in nursing home residents and staff as well as deaths from the disease in nursing homes for each state.

The data is reported by nursing homes and collected by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention through its National Healthcare Safety Network. This system is used, the CMS reports, “to ensure a nationwide, standardized process of collecting COVID-19 data from nursing homes in each state, as each state may have different reporting requirements for their nursing homes.”

Zucker points out, for example, “... there remain 13 states that report no information on nursing home fatalities and only nine states, including New York, report nursing home fatalities that are ‘presumed’ COVID and not confirmed COVID.”

Too much of our nation’s response to the pandemic was left up to individual states when, by its very nature, a pandemic is all-inclusive and must be dealt with that way.

We urge a federal requirement that all states use the CDC’s National Healthcare Safety Network so that reports of nursing-home deaths are both consistent and accessible.

The CMC website features an interactive map that allows the user to click on an individual nursing home to learn how many confirmed and suspected cases and how many deaths from COVID-19 there have been at a particular nursing home.

All nursing homes should be required to file this information so that it is readily available to the public.

We would urge our legislators, rather than focusing solely on the numbers for where deaths occurred or where the fault lies for not releasing those numbers earlier, to look at the other substantial problems raised by the attorney general’s report and to set about solving them.

As with so much else in our society — from racism to poverty — the pandemic has laid bare problems in nursing homes.

The attorney general’s investigation found that nursing homes with worse staffing ratios had more COVID-19 deaths.

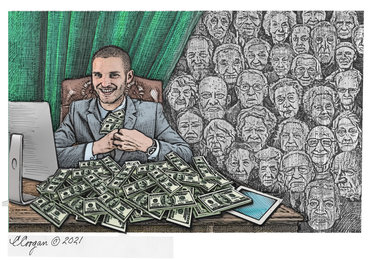

Most of the state’s nursing homes — 401 — are for-profit, privately owned and operated entities as opposed to 189 not-for-profit facilities, and 29 government facilities. More than two-thirds of the for-profit facilities have the lowest possible CMS staffing rating of one star or two stars. Similarly, of the 100 facilities in New York State with a CMS one-star overall rating, 82 are for-profit facilities.

“Financial incentives within the current system,” the reports says, “result in a business model in too many for-profit nursing homes that: (1) seeks admission of increased numbers of residents to reach census goals; (2) assigns low numbers of staff to cover the care needs of as many residents as feasible; and, (3) transfers facility funds to related parties and investors that the home could otherwise invest in staffing to care for residents — essentially taking profit prior to ensuring care.

“In this model, hiring additional staff above the numbers set in low staffing models, and/or offering a higher wage in order to obtain more employees in the current labor market, are viewed as optional and unnecessary expenses.”

The attorney general’s report is filled with heartbreaking examples,

At one New York City for-profit nursing home with critically low staffing, a son voiced concern about the care his mother was receiving. His mother was never tested for COVID-19, but later died while exhibiting COVID-19 symptoms, the reports says.

At one point, between late March and early April, when supervisory staff was ill, onsite management of that entire facility was in the hands of just two nurse supervisors. “Two to three weeks later, residents started dying from COVID-19. During the week of April 5, 33 residents died — 15 percent of all the patients in the facility,” the report said.

Across the state, nursing-home workers were struck with the disease at the same time nursing-home residents were, requiring more attention and the following of pandemic protocols. “These decreases in staffing levels occurred at the same time that necessary visitation restrictions removed the supplemental caregiving provided pre-pandemic by many family visitors at low staff facilities,” the report said.

At an upstate for-profit facility, a Certified Nursing Assistant alleged that it was common to have only one or two CNAs per unit since the start of the pandemic. “The CNA added that prior to this, there were ‘some’ staffing issues but it ‘was not this bad.’ The CNA alleged residents are ‘lucky’ to ‘get toileted and cleaned up once a shift … there is not enough time in the day to do it more than that.’”

The attorney general’s report recommends a four-pronged approach to the understaffing problem that turned deadly during the pandemic.

Direct-care and supervision staffing levels should be expressed in ratios of residents to Registered Nurses, to Licensed Practical Nurses, and to Certified Nursing Assistants. This would let residents and families placing residents in nursing homes know where they stand from the start.

Second, calculation of sufficient staff should include adjustment based on average resident acuity. Third, facilities with low CMS staffing levels should have more staff. And, finally, there should be enough staff to meet the needs outlined in residents’ care plans.

Further, the attorney general’s report recommends requiring “additional and enforceable transparency in the operation of for-profit nursing homes, including financial transactions and financial relationships between nursing home operators and related parties, and relatives of all individual owners and officers of such entities with contractual or investor relationships with the nursing home.”

Currently, the report notes, through a variety of related party transactions and relationships, owners and investors of for-profit nursing homes can exert control over the facility’s operations in a manner that extracts significant profit for them, while leaving the facility with insufficient staffing and resources to provide the care that residents deserve.

We urge our legislators to set aside politics and work to see that these problems are dealt with. Nursing-home owners should not be able to profit from government money meant to help their elderly residents, and staffing levels should be adequate to maintain good care.

In the meantime, we urge our readers who have or are about to have someone they love placed in a nursing home to follow the advice given in the report — to consult the CMS Care Compare online database, and to ask questions of nursing homes relating to staffing, policies, procedures, and recent and current COVID-19 infections of staff and residents.

Finally, those with people they love in nursing homes must continue to report any suspected neglect or abuse to the state’s health department or attorney general’s office.

In 1954, when she was in her sixties, Pearl S. Buck, the first American woman to win the Nobel Prize for Literature, wrote in her memoir, “Yet somehow our society must make it right and possible for old people not to fear the young or be deserted by them, for the test of a civilization is in the way that it cares for its helpless members.”

Let’s see that, here and now, our society does a good job of caring for its elderly members.