New York state needs a single, enforced standard of assessment

The Guilderland school district is in a bind.

It has far less in savings than its Suburban Council peers.

Aside from facing all the same challenges as other local school districts — from the pandemic, inflation, and increased costs for transportation and health care — Guilderland has an added one: tax certiorari cases.

“We have paid out $5.7 million in tax certiorari claim refunds and face an additional significant refund with Crossgates, which is still in the midst of being finalized,” Guilderlalnd’s assistant superintendent for business, Andrew Van Alstyne, told the school board at its January meeting.

He also said, “That is by far the single biggest explanatory variable in understanding why our reserves are smaller than our peers.”

The district had been proactive, setting up a special reserve exclusively to handle tax refunds. But that was wiped out and the district had to resort to bonds.

Van Alstyne stressed the importance of having reserves to “smooth out our year-to-year budgets. With financial challenges, reductions have to come somewhere,” he said. “The tax cap constrains our levy increases.”

He concluded, “And finally, having a strong tax base and having strong schools is a key contribution to a vibrant community with rising property values.”

He’s right: We all benefit — not just residents with children — when our schools are strong.

The stream of tax challenges started after Guilderland went through town-wide property revaluation in 2018. Guilderland had not undertaken revaluation since 2005 — a gap of 13 years.

This led to a tax revolt in 2017.

More than 100 angry and frustrated residents turned out at Guilderland’s Town Board meeting that September to ask the board for help in fighting tax bills that had gone up by hundreds of dollars or more since the previous year as a result of a new state-set equalization rate.

Supervisor Peter Barber called the state’s system “corrupt” and “crappy.”

In August that year, the town had unsuccessfully challenged its equalization rate, arguing before the New York State Office of Real Property Tax Services Board that the state’s system is flawed both because it merely samples values and it does not look at a county in its entirety, which creates disruptions in communities.

Guilderland’s assessor at the time, Karen VanWagenen, told us then that the reason she pursued the appeal was not to prove she was right. “When equalization drops like that, what it does for the next year is it reduces the value of people’s exemptions … I know what it would do to each person,” she said, naming those who get veterans, age, agriculture, and business exemptions.

The town then decided to undertake the expensive and laborious process of revaluation.

Guilderland had moved to full-value assessment in 1980 and had at first conducted townwide revaluations every four or five years.

That is a better strategy, keeping assessments close to full-market value so that state-set equalization rates don’t wreak havoc for taxpayers.

Guilderland is in much better shape than other towns we cover.

Hilltown residents once burned their tax bills in front of the Knox Town Hall. The Hilltowners were as hot as the flames in their burn barrel. Some were paying more than their fair share and they weren’t going to take it anymore.

The system of taxation in the Hilltowns was badly skewed and there was an uprising when an outside firm was hired in the late 1990s to set property values. Farmers were particularly upset that their land was going to be appraised at building-lot prices.

Town hall meetings in Berne and Knox were packed for many months. When election time came, some board members lost their seats.

But some courageous and sensible officials stayed the course. Property revaluation was completed in Berne, Knox, and Rensselaerville.

Westerlo, however, withdrew from the project and has not revalued properties for decades. The state-set equalization rate for Westerlo is less than 1 percent; this leaves newcomers with an unbelievably unfair tax burden.

And the other Hilltowns haven’t undertaken townwide revaluation since their courageous undertaking a quarter-century ago.

For decades, we have written on this page, urging towns to move to full-value assessment and to update their rolls regularly. The goal, of course, is to have an equalization rate at 100 percent.

The point of the state-set rate is to have taxpayers pay their fair share. If a house in Westerlo is assessed for, say, $1,000 when it would actually sell for $100,000, the owner of that house should be paying the same county or school taxes as a person who owns a $100,000 house in a different municipality.

With county taxes this year, property owners in Berne and Westerlo were hurt because, although the county’s levy — roughly $100 million — has been the same for three years, equalization rates in those towns dropped, much as they did in Guilderland in 2017, causing tax rates to go up.

Berne’s equalization rate dropped from 50 to 43 and its county tax rate went up 5.4 percent while Westerlo’s equalization rate dropped from .75 to .64 and its county tax rate went up 5.8 percent.

Town leaders should ease the burden on their residents by undertaking townwide revaluation. There is no state enforcement mechanism.

As we can see in Guilderland, residents and especially businesses resort to lawsuits to pay less. This not only burdens the court system but it makes it difficult for entities, like schools, to plan their budgets and meet their needs.

While it is true that the burden shifts to other taxpayers in, say, a school district, it doesn’t mean that the school can still get the money it has budgeted since there is a state-set levy limit that is difficult to override with a public vote.

While the best that municipalities can do for their residents is revalue regularly, a statewide solution is what is needed.

Unlike most states, New York has no law requiring revaluation at certain intervals.

As Van Wagonen made clear in 2017, a dramatic drop in equalization rates hurts the town’s most vulnerable residents.

This sort of chaos and pain could be avoided by needed change at the state level.

When Guilderland challenged its rate in 2017, Paul Miller, director of Regional Service for the Office of Real Property Tax Services, said that having New York allow each individual municipality to set its own assessment level was a “nightmare scenario.”

“We have 1,000 jurisdictions,” said Miller. “We let them set their own assessments. Most states have a single standard of assessment.”

The state’s current system of setting an equalization rate, based on small, random sampling, can lead to inaccuracies.

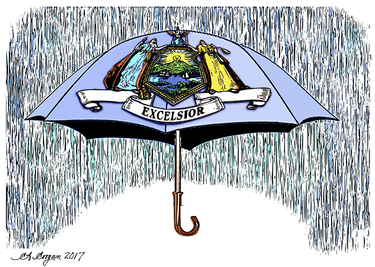

New York state must do away with the “nightmare scenario” and must set a single standard of assessment — an umbrella in the storm of changing property values — that is enforced statewide and thereby protects taxpayers.

This will reduce the load for the state workers who now deal with 1,000 different standards.

It will save residents from skewed tax rolls and unequal burdens. It will take the heat off of local officials who, as in Westerlo, have not made the commitment to fairly assess property.

In the end, it will guarantee that residents across the state are each paying their fair share of taxes.

In 2018, the state legislature passed several bills to ameliorate the crisis in Guilderland. One, for example, improved notification statewide so taxpayers would be forewarned if there were going to be a surge in tax rates because of a drop in equalization rates.

But these laws did not solve the underlying problem.

Assemblywoman Patricia Fahy, who sponsored these bills, said at the time, “I have heard that maybe, if they had a standard rate throughout the state, we wouldn’t have these machinations, but my understanding is that there’s such a history of doing it this way that it’s just become more politically entrenched.”

Fahy added, “That will be a much more complete fix.”

That is precisely what we need — a complete fix.

Now is the time for our state representatives to crawl out of their political trenches and act on a statewide system.

As Guilderland’s supervisor said seven years ago: The state’s system is “corrupt” and “crappy.”

Why should New York’s taxpayers tolerate that?