Remembering that other country: Inauguration Day, 1961

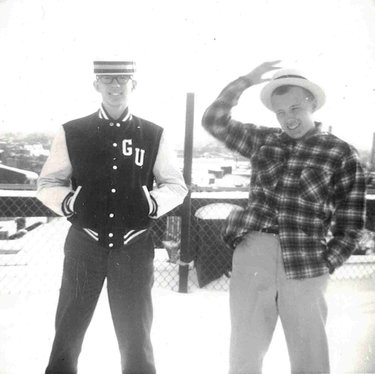

Rooftop Hoyas: That's me on the right. This photo of Charlie Hanrahan and me may have been taken on the roof of our Georgetown dorm, very possibly on Inauguration Day. The straw boaters are still worn by Hoya basketball fans, I believe. Charlie hailed from Monkey's Eyebrow, Kentucky, and came from a family prominent in the states politics. It may have been Charlie's Washington connections that got us into the Democratic do at the Hilton on election night. I hope we didn't wear those boaters to the inauguration.

He was 43. I was 18. He was the youngest man ever elected president of the United States of America. I was a freshman at Georgetown University, a very old Catholic University about four miles to the west of the United States Capitol building.

Now, 57 years after the inauguration of John Fitzpatrick Kennedy on Jan. 20, 1961, I look back at that day through the prism of all that has happened since, trying to bring into focus again that distant time when some classmates and I stood in freezing post-blizzard temperatures, cheering lustily for someone we saw as a new kind of president. A better kind. Or at least that’s the way we saw this handsome Bostonian with the beautiful and elegant wife, and with a family backstory of immigration from Ireland and hard-won success with more than a whiff of ruthless ambition. Yes, pass the torch to a new generation, that’s very OK with us!

Sure, we liked Ike, but who didn’t? And that thought helps bring into focus something that confirms the adage that the past is a foreign country. Politics wasn’t a blood sport then. The other party wasn’t the embodiment of all that is wrong with the country; those in the other party just had some sadly mistaken ideas.

Ike’s would-be successor, Richard Nixon — himself quite young — just didn’t give off that cool Kennedy vibe that announced the future is here. My classmates and I were confirmed Democrats anyway, all of us reared in households that revered Franklin Delano Roosevelt.

We were also from way outside the Beltway (which I just learned online was under construction in 1961, so my use of that metaphor for insiders and outsiders is anachronistic). Our homes were in California, Ohio, Kentucky. But we were all political junkies, and here we were in the center of it all, in the midst of the most historic election in all of world history!

On a golden autumn Sunday in 1960, my parents had moved me into my dorm room in a former hospital, into a ward-like room big enough for four of us freshmen.

That done, we walked west on N Street. OMG (another anachronism). There, espied by my mother, walking along the brick sidewalk opposite, were John and Jacqueline Kennedy with baby Caroline in a stroller. They lived in the neighborhood and perhaps were returning from Mass at Holy Trinity Church around the corner. My mother pulled us across the street, bound and determined to meet the candidate and his family.

But here’s the thing. There was no security, at least none in evidence. No one threw himself between us and my mother’s target. The Kennedys paused. We shook hands. He was polite, she silent. We wished him luck, very sincerely. No selfies were taken. In fact, no photo was taken. We had no camera. So you’ll have to take my word for it: Yes, we did meet the Kennedys on their way home from church. Just ordinary folks, like us.

A little over a month later, John Kennedy was president-elect. On election night, we Hoyas- for-Kennedy went to the Hilton Hotel downtown, where the Democrats had assembled to watch the returns come in. It was a cliffhanger and we left in the wee hours, with the winner still uncertain. Some say Richard Daley, the mayor of Chicago, had found the votes to push Kennedy across the finish line. No charges of rigging or illegal voting erupted, however. None that I remember anyway. It was a more pacific time.

Later, some time after the election, a group of us “Georgetown gentlemen,” in the coats and ties we wore to class, planted ourselves opposite the Kennedy townhouse near the campus, where the family was still living before moving downtown to the White House. I guess you could say we were staging a demonstration, of the politest kind possible. We had homemade signs we wanted the president-elect to see. A piece of advice.

“Stevenson for State,” our signs said. We fervently wanted Adlai Stevenson — the urbane liberal senator from Illinois who had been defeated by Eisenhower in 1952 and again in 1956 — to be appointed Secretary of State. The New York Times put a photo of us on its front page, if my memory serves me correctly, which it doesn’t always do. The president-elect must have half-heard us: He made Stevenson ambassador to the United Nations. Not bad for a bunch of freshmen.

But the best was yet to come: The official swearing-in of our man, witnessed by what was sure to be a record-breaking crowd assembled below the east front of the Capitol. Ronald Reagan was the first president to be inaugurated on the west side of the Capitol, in 1981, a move that allowed for crowds of Biblical proportions (or not) to assemble on the National Mall stretching into the far distance. Much more commodious than the rather modest plaza on the east side of the building.

Nature, however, had its own plans for Mr. Kennedy’s big day. A nor’easter blizzard rolled up the coast the day before and deposited about 8 inches of snow on inauguration eve on a city that could be paralyzed by snow ridiculously easily.

I don’t think anyone seriously proposed postponement. After all, the Constitution itself calls for the swearing-in to take place exactly at noon on the 20th day of January.

No buses were running. None of us had a car, which probably couldn’t have gotten through anyway. We set out, our little band of Kennedy loyalists, and walked through the snow right down the middle of Pennsylvania Avenue, which the blizzard had closed down. It must have been exhilarating, walking four miles on that crisp bitterly cold morning, the sky clearing, the snow no longer falling.

I don’t remember crowds streaming down the avenue. I just remember us, heroically struggling onward.

There was a pretty good-sized crowd assembled by the time we got there. I have no idea how they got there. Not by public transportation, that’s for sure. (The Metro mass transit system had yet to be built, by the way.) Maybe they were just folks from the neighborhood.

No Jumbotrons enlarged the dignitaries for us. But we enjoyed the heck out of the whole occasion. It was delicious when the podium started smoking during the invocation from Cardinal Richard Cushing. And it was very fine when that Boston-accented voice rang out in the cold clean air, solemnly swearing the oath all presidents swear.

And it was very poignant when the 87-year-old poet Robert Frost, his fine white hair tossed by the wind, stepped to the podium but couldn’t read the poem he had composed for the occasion because of the glare of the sun on the page. I think the new president tried to help. But finally Frost, who was to die two years later, gave up and recited from memory his poem “The Gift Outright.” It begins, “The land was ours before we were the land’s.” It’s a poem about how Americans finally learned to give themselves to the land — “the deed of gift was many deeds of war.” But the nation is still unfinished: “...still unstoried, artless, unenhanced, / Such as she was, such as she will become.”

The old seer seemed to me striking a mystical note that probably left the crowd, including the four freshmen, puzzled.

But there was no doubt what the new president meant when he said in his stem-winder of an inaugural address: “Ask not what your country can do for you, ask what you can do for your country.”

We cheered that fine rhetoric as loud as everyone else did. And I suppose we thought we were already doing OK in the doing-for-country department. After all, we had made it to the Inauguration, hadn’t we? And it wasn’t easy.

So every Inauguration since, I think back on that one, when the country and I were younger. More idealistic. And definitely more hopeful.

Editor’s note: This is Tim Tulloch’s last stick of type for The Altamont Enterprise. After eight months of covering the Helderberg Hilltowns, Tulloch has decided to “re-retire” as he put it. We will miss him.