County recommends more than 30 projects to mitigate climate-change impacts

ALBANY COUNTY — Albany County is counting the ways it’s threatened by climate change, and outlining the steps it can take to protect itself.

In its draft climate-resiliency plan, the county details, in 270 pages, 20 long-term, large-scale projects it should undertake to protect its residents from the adverse effects of climate change, in addition to several smaller-scale projects.

“The threats [of weather] are not new,” Albany County’s Economic Development and Sustainability Coordinator Luke Rogers said at a public-input meeting about the draft plan earlier this month. “It’s the frequency and severity that has increased over time, and we see that nationwide. We see it globally. There’s a lot we can do to fight climate change — we take seriously reducing our emissions — but that is really a regional, national, and global issue.

“Arguably, on the resilience front, there’s even more that we can do to directly prepare the county to address and be ready for these climate threats when they do arise,” he said.

Risks and assets

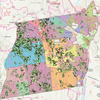

The threats mentioned by Rogers are primarily heat- and flood-related, in Albany County’s case, and the plan reveals the degree of risk that residents face through a highly detailed map that assigns parcels one of six descriptors, ranging from “minimal” risk to “extreme” risk.

All the towns in the Enterprise coverage area appear to be mostly at “minor” risk — the second-lowest rank — but each has a significant area determined to be at moderate, major, or severe risk. The highest risk-areas in the county are within the city of Albany, and are predominantly along the bank of the Hudson River, but Coeymans has the greatest degree of risk over the largest area, with the entire town appearing to be at moderate risk or greater.

These rankings compile subscores related to:

— The estimated chance of flooding and its severity as determined by First Street Foundation;

— The risk of heat as determined by the New York State Department of Health; and

— Social vulnerability in each parcel as indicated by data from the state’s Department of Environmental Conservation and Energy Research and Development Authority, and by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

In The Enterprise coverage area, flooding is the highest risk to residents compared with heat, which is considered a minor risk everywhere except in Rensselaerville, in a portion of Guilderland, and in Voorheesville, where it’s a moderate risk.

That same portion of Guilderland — slightly northeast of Voorheesville — the village of Altamont, and a bit of Westerlo and New Scotland are considered to be beyond the lowest score for social vulnerability, with all those areas except Altamont containing “major” vulnerability, the third-highest of five possible rankings. Altamont is considered “moderate.”

All areas within Albany County have at least a “minor” ranking to account for individual circumstances, the plan explains.

Besides hurting people directly, the plan says, heat and particularly flooding can disrupt services critical to health, safety, and quality of life. So, while flooding may not be a risk in a particular parcel, it can still create danger for people by removing an important service.

The plan indexes and maps all the various assets inside the county that it wants to protect, which fall into one of the following categories: housing, infrastructure systems, health and social services, national and cultural resources, and economic systems.

Fire departments in Rensselaerville, Guilderland, and New Scotland are at an “extreme” flood risk by 2050, meaning that there’s at least a 27 percent chance of these facilities being flooded by at least two feet of water in the next 30 years. Voorheesville Elementary School is also considered to be at an extreme risk of flooding.

Two reservoirs in the Enterprise coverage area are at Also at extreme risk of flooding: the Watervliet Reservoir in Guilderland and the Vly Creek Reservoir in New Scotland.

At “severe” risk of flooding are the Westerlo Rescue Squad building, the Mohawk Hudson Humane Society facility in Menands, and the Guilderland wastewater treatment plant.

Projects

The 31 projects recommended within the plan are split into two tiers, with Tier 1 projects being those that are relatively easy to implement because of their scale and, in some cases, already partly finished.

These projects are:

— Inventory greenhouse gas emissions from county facilities and operations;

— Electrify county buildings;

— Electrify the county’s vehicle fleet;

— Install electric-vehicle charging stations on public properties;

— Pursue renewable energy generation on county property;

— Retrofit streetlights to light-emitting diodes;

— Participate in the Climate Smart Communities and Clean Energy Communities programs;

— Support the Nature Bus program, which takes urban residents to park locations, and other initiatives to expand access to public transit;

— Provide climate-risk data to the public and the development community;

— Conduct an energy-resilience study; and

— Conduct a communications and broadband resiliency study.

Tier 2 projects are bigger and more complicated than those in Tier 1, the plan says, and may require cooperation between various municipalities and/or agencies.

These projects are:

— Increase county capacity to support resilience efforts;

— Create a Climate Justice Corps network;

— Purchase First Street Foundation’s Flood Factor data;

— Support municipal participation in the c0mmunity rating system for floodplain management run by the Federal Emergency Management Agency;

— Create a “Resilient Homes Program”;

— Build out the county’s network of rain and stream gauges;

— Conduct a county-wide culvert analysis;

— Conduct a county-wide transportation vulnerability assessment;

— Increase resilience at municipal facilities;

— Plan for sea-level rise at the county’s north and south wastewater treatment plants;

— Increase resilience to extreme temperature events;

— Prepare for long-term and large-scale displacements;

— Expand the county-wide trail network;

— Create a “Green Streets Initiative”;

— Develop a county-wide open-space plan;

— Create a “Business Resiliency Program”;

— Develop a “Sustainable Albany” campaign;

— Create a network of demonstration projects;

— Advance the resiliency recommendations included in the County Agricultural and Farmland Protection Plan; and

— Create an “Agricultural Resiliency Program.”

Project specifics

The plan details specific steps the county should take for each project — some to a very high level — as well as potential funding sources.

The climate justice corps project, for instance, involves seven actions: become a host community for a NYSERDA climate justice fellow; develop a list of climate-resiliency actions this fellow would work on, such as tree-planting or trail and open space maintenance; create a workforce training program that targets youth in vulnerable communities to develop skills necessary for other resiliency projects; create a guide for municipalities to start their own corps; find partner organizations; establish a corps-to-workforce pipeline; and identify renewable funding sources.

Potential partners include Cornell Cooperative Extension, the Albany County Land Bank, the Stormwater Coalition of Albany County, and the Pine Bush Preserve, among many others, the plan says.

The timeline to complete all actions for the justice corps is 10 years, the plan says, and would cost $40,000 up front to fund the climate fellow position.

Funding might come from NYSERDA or the federal Environmental Protection Agency, the plan says.

The resilient homes project, on the other hand, primarily involves outreach, though the plan suggests that the county develop a guide for homeowners to educate themselves on the benefits of “green infrastructure,” as well as financial and technical assistance.

Green infrastructure includes things like trees, cisterns, and porous surfaces that reduce the likelihood of flooding and erosion on a property.

Between developing a guide and conducting outreach, the plan estimates this project to take about five years to implement and would be kept up indefinitely from there. The estimated cost for the guide is $100,000, with funding possibly available from FEMA, the New York State Environmental Facilities Corporation, and New York State Homes and Community Renewal.

The green-streets project is similar to the resilient-homes project in that it involves increasing the amount of green infrastructure, but in this case it would be along roadways and would be undertaken by governments rather than homeowners. Benefits go beyond climate resiliency, the plan says, extending into mental health, since studies have shown that sufficient tree cover can reduce stress.

Steps include the county planting many, many trees — the plan offers 40,000 as a potential goal — in areas where trees are more scarce, and working with communities to raise awareness of this project while helping them connect to funding sources. No timeline or project up-front cost is provided in the draft plan, but potential funding sources include various state agencies as well as the federal Healthy Streets Program.

To benefit rural areas, where agriculture is at risk because of flooding and heat, the plan encourages the county to follow through on its agricultural and farmland protection plan, which was last updated in 2018.

Specifically, the draft resiliency plan says the county should establish a critical farm loan program to help would-be farmers buy up agricultural land that’s at risk of being used for non-agricultural purposes, such as residential development, and provide new farmers financial incentives to meet certain conservation goals.

It also suggests that businesses that support farmland be recognized as “essential” to help sustain farm operations.

No timeline is provided, except that a task force should be established in the “near-term,” and the farmland protection plan is referred to for cost estimates.

“A big part of being resilient is that we can have a local agricultural economy that in times of emergency could provide local food for our communities,” said Liz King, of Bergmann Associates, at the meeting.