Blacke stinking fume — a good smoke

— Photo from the Guilderland Historical Society

Wm. D. Frederick’s Center House in Guilderland Center was typical of small rural hotels with a bar providing most of his profit. His 1887 account book, now at the Mynderse-Frederick House, shows that additional income came from the sale of cigars and tobacco. The entrance to Park Guilderland is on the site today.

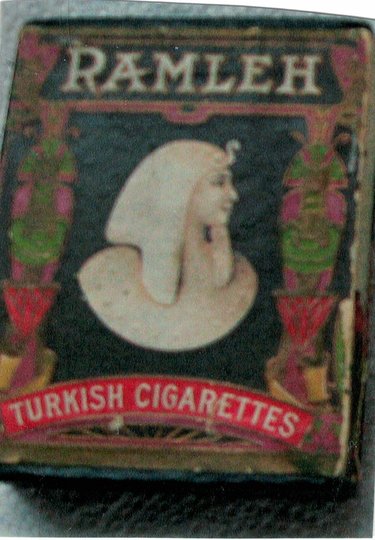

— Photo from Mary Ellen Johnson

Ramleh Cigarettes came in a beautifully colored box and was produced until 1911 when the name was reversed to Helmar because the name of a competing brand of cigarettes sounded too much like Ramleh. Joe Gaglioti, Altamont’s barber, advertised Helmar cigarettes for 15 cents a pack in 1921.

Tobacco has been a feature of American life ever since it was introduced to Europeans in the late 15th century. When presented to King James I in 1604 his judgment was: “hatefull to the Nose … dangerous to the lungs” with a “blacke stinking fume … .”

Unfortunately, most men found tobacco use a pleasurable habit, whether smoked, chewed, or inhaled as snuff. During the colonial period, it was known to be used in the Albany area, but we cannot document its presence in what became Guilderland during those years. However, by the end of the 18th Century, written references begin to surface.

The late town historian Arthur Gregg reprinted portions of old account books that he had the opportunity to examine. In the 1790s, Mr. Frederick Crantie (Crounse) listed among other items “9 lbs of sn’ff” and on another occasion 16 shillings for tobacco.

When the old Severson Tavern building was about to be demolished in the 1950s, Gregg got a look at Severson family papers. The tavern, once a busy stopping place on the Old Schoharie Road at the foot of the Helderberg escarpment (now the site of Altamont’s Stewart’s Shop), was run by Jurie Severson who kept careful accounts.

In 1813 to 1814, transactions included selling Jess Secord a “segar” for one pence, Mr. William Gardner segars for six-and-one-quarter pence, Mr. Lot Hurst a segar for one cent, and segars to Nad Groat for five-and-one-quarter cents.

Note that, in the early days of the Republic, English and American denominations were used interchangeably. Also among the Severson papers were recipes for medical treatments and among them was one for fever sores that included tobacco as an ingredient.

After Jurie Severson’s death, his son George continued to operate the tavern, recording in his account book at various times: snuff, 7 Spanish segars, and 2 lbs tobacco.

Another of our early town historians, William Brinkman, mentioned an 1816 account book probably kept by a merchant in Dunnsville who recorded the sale of ½ lb Pigtale, an early form of tobacco.

Civil War soldiers were fond of tobacco. Abram Carhart was a Guilderland recruit in the 177th New York Volunteer Infantry, a regiment assigned to the area of the Mississippi. His diary is now at the Mynderse-Frederick House in Guilderland Center. On May 16, 1863, Carhart recorded selling A. Fox, who promised to pay when back in camp, some tobacco for 5 cents, and two days later, sold to Billy (last name illegible) some tobacco for .50 cts. Shortly after, the unfortunate Carhart accidentally drowned in the Mississippi River.

Once The Enterprise began publishing in 1884, it becomes possible to survey tobacco’s use in our town through its local columns, ads, editorial content, fiction, humor, and articles. Among many Guilderland males, similar to American men in general, tobacco had a place in their lives.

Tobacco use among 19th-Century women in the Northeast was very rare until cigarettes became common in the 20th Century, and only in the 1920s do women begin to smoke in great numbers.

The earliest tobacco ads in The Enterprise were tiny one-line fillers mixed in with other information or listed in a weekly column called “Business Locals.” Men were urged to “Smoke the Pride of Knowersville, 5 cent cigars., “Try Gallop and Johnson’s Augusta 10 cent cigars,” or try “Old Honesty Cigars” manufactured by C.F.Dearstyne, an Albany firm.

These were only samples of many other cigars named. These and other one-line cigar notices pop up week after week. Later in the 1890s, some of the cigar ads were larger with the cigars actually pictured.

Male bonding

Through the newsy local columns between 1884 and the entry of the United States into World War I in 1917, cigar-smoking men were mentioned, especially on occasions of male bonding and jolly fellowship, reflecting the popularity of cigars during that period.

“Hornings” seemed to be a common masculine custom occurring either when the new bride and groom arrived home from their wedding trip or many times immediately after the wedding celebration itself. The couple could expect the local fellows to turn up making lots of noise as they did to D & H Conductor Gilroy and his bride when the guys treated them to an “old time serenade with the band being out in full force with drums, horns, guns and every conceivable noisemaking instrument.”

The raucous visitors were “thanked heartily with cigars.” Repeatedly, descriptions of hornings from all over Guilderland mention that cigars were passed out to the male noisemakers.

Male bonding was definitely the order of the evening after an 1895 meeting of the Altamont Hose Company when Mr. H. Van Schoick treated “the boys who used the weed with cigars from a ‘unique’ [quotations in the original] server, which we dare not say were the less enjoyed because of the manner in which they were ‘set up’.” We’ll just have to use our imaginations on that one!

Or the time in 1894 those avid cyclists, the Altamont Wheelmen, were treated at the close of their meeting by their president and secretary to an oyster dinner followed by cigars.

New fathers were expected to pass out free cigars with the arrival of their babies. In 1896, “a new clerk registered at the Dunnsville Hotel February 28 and judging from the smiling proprietor, we think he will stay. Set up the cigars, Billy.”

Simple social occasions brought out after-dinner cigars. A group of Guilderland Center couples camped out near Thompsons Lake where “Mr. Hallenbeck passed out his choicest brand of cigars and while the ladies did up the dishes, the men enjoyed quite a smoke on the mountain. This was also the custom indoors after a dinner party if the host were a smoker.

Cigars were used in wagers, as prizes, possibly election bribes, or as a reward. Rufus Wormer to bet cigars no one could top his flock of 18 productive Guilderland Center hens which laid 310 eggs during March 1896.

An 1895 law forbade gambling in all forms including tossing a roll of the dice at a hotel bar for a drink and a cigar. Men who turned up at the First National Bank of Altamont’s opening day in 1912 were given cigars while ladies got carnations.

And did “Site” Secor spend $1.15 for cigar bribes in his election bid for Altamont village trustee in 1892 or was he telling the truth that he passed them out after [italics in the original] the voting took place?

Then, in 1917, there was the generous reward given to the gentleman who found and returned a man’s pocketbook with the $40 it contained still inside. After counting it to be sure it was all there, the owner then “nobly rewarded the fellow’s honesty — with a cigar!”

Booming business

An 1884 statistic quoted in The Enterprise informed its readers that “the annual consumption of imported and domestic cigars is 60 to every man, woman and child in the United States.”

That cigars were popular locally is borne out by the amounts local merchants were willing to pay for the privilege of having the sole cigar concession at the Altamont Fair during Fair Week. In 1894, George Hallenbeck paid $100 to sell soft drinks and cigars, in 1896 W.H. Cornell paid $45 for cigars alone, while in 1898 C.W. Pitts paid $50 for the cigar privilege.

Assuming almost all cigars smoked locally were of the 5- or 10-cent variety, imagine how many cigars had to be sold to cover concessionaires’ costs and earn a profit.

The cigar industry of that period provided much employment. Locally, there were large cigar factories in Troy and Albany as well as smaller operations in rural locations like Central Bridge, Esperance, and Middleburg. In Guilderland Center, George Hallenbeck began manufacturing cigars in 1888. In 1899, he moved his operation to Voorheesville.

At one time, the number of employees in the Guilderland Center factory (now 490 Route 146) reached 15. The workers prepared the wrappers and rolled the cigars. In addition, two salesmen who were out on the road peddling Hallenbeck’s cigars with such names as Grand Racket, Little Gem, and Way Up. One reported selling 30,000 in two years.

An Altamont resident by the name of A. Gutekiest apparently worked alone in the mid 1890s. His “Little Tots” brand was considered an exceptionally fine cigar. Two sons of Junius Ogsbury, for a time part owner of The Enterprise, worked in New York City for the American Tobacco Company, a huge tobacco trust.

Moral grounds

While cigars may have been popular, there was a vocal minority of folks both male and female who were vehemently anti-smoking in any form on moral grounds, especially ardent temperance advocates.

An 1896 Women’s Christian Temperance Movement column warned, “The poisonous cigar and filthy cigarette are indulged in by many a mother’s son and produces a strong thirst and craving for strong drugs.”

The Rev. Talmage, author of a weekly sermon that appeared regularly in The Enterprise, was naturally opposed to all forms of sin. This Presbyterian minister cited the moral dangers of tobacco in a number of his lengthy sermons including this call, “Young men, drop cigars and cigarettes and wine cups and Sunday excursions.”

The Enterprise editor of 1896 may have fully agreed with these anti-smoking sentiments or may have just been catering to a segment of his readership when he inserted this quotation from the late Henry Ward Beecher: “I rejoice to say I was brought up from my youth to abstain from tobacco. It is unhealthy, it is filthy from beginning to end.”

The writer of an 1893 Guilderland Center column chronicled community events but ended by offering this opinion: “I think it would reflect credit on the town if horning on wedding occasions with its accompaniment of going to the saloon for a drink and a cigar were abolished. Let the practice go back to the heathen where it originated.”

There’s an aspect of tobacco use never mentioned in any local column: chewing tobacco and the expectoration that accompanied it on streets, on sidewalks, in public places, and on conveyances. Indoors sat the cuspidors that had to be cleaned out.

In an 1891 Chicago Tribune piece reprinted in The Enterprise titled “A Filthy Habit,” the author writes: “One of the vilest habits tolerated in the United States publicly and privately is wholly unknown in other countries. It is obtrusive expectoration. Men riding in public vehicles pay for transportation, but that does not include the right to defile floors, soil the garments of other persons, and sicken the stomachs of the sensitive. The bespattering of sidewalks, railway stations with salivary discharges is as foul as it is unnecessary.”

Chewing tobacco

In those days, The Enterprise printed many short pieces of fiction often mentioning some form of tobacco use. The story opens in “Chased by an Engine” when “the conductor rolled his quid from one cheek to another, raised the window by his side and expectorated in the outer darkness.”

“A Queer Kind of Ghost” has the line, “The man in the smoking compartment was chewing tobacco and at intervals, he spat into the cuspidor with the sibilant swish incidental to tobacco chewing.”

By 1901, New York State had outlawed expectoration on public conveyances, but a one-liner in The Enterprise suggested that, if someone invented a “pocket” spittoon, there would be a fortune in it. Gross and distasteful, but at that time tobacco chewers made up a sizable part of the nation’s male population and were an everyday part of life.

Any man who needed a tobacco fix could go to any of the local general stores and find either cigars or chewing tobacco. Hotel bars also had supplies for sale and ,in places like Albany, there were tobacco shops with any form of tobacco desired and accessories as well.

By now, it is obvious cigarettes have barely been mentioned. They were relatively new to the United States and a very controversial form of tobacco that came into common use only in the teens of the 20th Century.

Unlike cigar-smoking and tobacco-chewing, cigarettes were of foreign origin and required smokers to inhale. They were initially looked upon by a sizable number of Americans as immoral, filthy, and unhealthy. And horrors, women and boys might be tempted to take up smoking.

After encountering Turks and Russians smoking Turkish tobacco in rolled paper during the Crimean War in the 1850s, English and French soldiers brought the habit home where the French word “cigarette” became universal for this form of tobacco.

At the time of the Civil War, cigarettes were introduced into the United States, but did not catch on at first.

However, in 1880, James Bonsack, a Virginia inventor, patented a cigarette-rolling machine to which “Buck” Duke quickly purchased the rights. Duke, who had already been manufacturing hand-rolled cigarettes, now moved into mass production.

An aggressive businessman, Duke forced his cigarette-producing rivals into the American Tobacco Company, a monopoly eventually broken into four large companies under terms of the Sherman Antitrust Act of 1890.

Cigarette-smoking proved to be very controversial both because of the inhalation of smoke and the possibility that the smoking habit would be taken up by women and children. Beginning with Enterprise publication in 1884, the controversy over cigarette smoking was reflected in various articles, sermons, brief fillers, fiction, and advertising.

Foremost opposition came from the Women’s Christian Temperance Union, a powerful national organization with a very active membership in Guilderland, its chief objective being national prohibition of alcohol. The union’s members were opposed to cigarette- and cigar-smoking on the basis that enjoying a smoke could very possibly give you “an unnatural thirst and craving for strong drink.”

Expressed in their 1907 keynote address at the WCTU Convention was the opinion that cigarette-smoking is “a depraved and acquired taste that may be classed among opium habits.”

The Albany County WCTU voted to place handbills in public places to bring attention to the recent passage of an 1889 New York State statute banning sales of cigarettes, cigars, and tobacco in any form to anyone under the age of 16. They also held anti-smoking sessions in local Sunday schools.

A second national organization with many Guilderland members firmly opposed to cigarette-smoking was the Grange, officially known as the Patrons of Husbandry, which adopted resolutions at its national conventions several years running against cigarettes and whiskey.

Cigarette fiends

Sermons printed in The Enterprise classified cigarette smoking as a moral issue. For Dr. Talmage, “filthy” cigarettes along with cigars would lead to worse vices.

Edwin A. Nye, who wrote “Heart to Heart Talks” about a variety of moral problems, in a 1906 “talk” illustrated how cigarettes were related to criminal behavior. Based on the experiences of New York City Police Inspector McCafferty, 85 percent of the people arrested are “cigarette fiends,” he wrote.

Making a close connection between cigarettes and crime, Nye emphasized these are not just the feelings of an anti-smoking society nor are they the statements made by “crank reformers,” but based on information given by police officers, physicians, newspaper reporters, men who know. Young men were advised “CUT OUT THE CIGARETTES” [caps in the original] and if you MUST smoke, use a pipe or cigar. Do not use cigarettes.

“A Cigarette Fiend” was a short article recounting the sad story of a young man who had to be committed to an asylum because he was a “cigarette maniac.” Quoting his poor mother who said, “Thank God, he cannot get cigarettes to make him crazier.”

A brief filler described another man, awaiting his imminent execution on Sing Sing’s death row, “coolly” smoking cigarettes.

Effects on health

Critics deplored the negative effect cigarette smoking would have on health.

“Definition of a Cigarette” informed Enterprise readers, “A cigarette is a roll of tobacco and drugs,” claiming that their use gave smokers nightmares, cancer of the lips and stomach, spinal meningitis, and softening of the brain.

One filler made the outrageous statement that scientists claimed that smoking led to idiocy, while another deemed smoking cigarettes damaging to the optic nerve. A Professor Leflin stated cigarettes contained five poisons including opium.

For some reason staunch opponents of cigarettes claimed they were a narcotic and with opium as part of the content. A Dr. Holmes flatly stated the habit of smoking cigarettes “enfeebles the will power.”

More accurate were English doctors who after a study of a large number of cigarette smokers discovered a disproportionate number of them had heart disease. English doctors also feared that chronic smoking would lead to cancer of the mouth or throat.

Instinctively many people of that era knew that cigarette smoking was unhealthy, but ironically no one except James I in 1604 seemed to connect smoking with lung problems.

The prospect of boys smoking cheap and readily available cigarettes was especially disturbing. A 1900 Village and Town column carried the warning that “the time is coming when a boy will have to choose between a cigarette and a job ... The boy who smokes cigarettes will not be fit for anything else, the fumes of a cigarette will sooner or later clog the machinery of the brain and render him the intellectual equal of a fish worm.”

In Canada, it was reported that Parliament was trying to halt sales of cigarettes to boys because deaths had resulted from their poisonous effect and in other cases rendered them “dopy and unfit to work.”

An assembly at Altamont High School in 1915 featured an Albany lawyer and builder lecturing students on “The Cigarette Problem,” emphasizing to them, “The cigarette kills by degrees. It stupefies the mind, kills determination and the power to say ‘no’ and makes young men useless, soulless and worthless.”

“Vile habit” for women

Another distasteful possibility was that of women smoking.

As early as 1885, a scary mention of “fast” girls smoking for fun, warning them the habit of smoking would “unsex” them with the result they would lose all reverence due to womanhood.

And the WCTU weighed in with: “There is no more degrading and damaging habit to the human race than the smoking of women. It is a vile habit and those women who do so must be weak and are liable to fall into any habit that may come their way.” Dr. Talmage condemned it in his “Fourth Sermon to the Women of America.”

In those days, The Enterprise regularly ran short pieces of fiction with men smoking cigarettes and occasionally women, though they always seemed to be English women.

The cigarette habits of foreign countries brought much attention with mentions of smoking in Cuba, the Philippines, France, Russia, Chile, Spain, Mexico, Egypt, Austria, England, Bulgaria, Japan, Borneo — the list is very long. And often the foreign women were smoking regularly in what seemed to be acceptable fashion.

Big Tobacco

The anti-smoking crowd didn’t have a chance against Big Tobacco and by 1913 the tide was definitely running against them. The cigarette and tobacco producers began to pump huge amounts of money into advertising, even in weekly country journals like The Enterprise.

Large ads began to show up with Bull Durham tobacco quite prominent. In 1913, only five cents bought a sack of one-and-a-half ounces of choice Virginia and North Carolina tobacco called Duke’s Mixture. There was supposed to be enough to make many good-quality satisfying cigarettes, the kind that makes rolling popular. Not only that, but you got a coupon and could send away for a coupon catalog. Save enough and you would get a prize.

Ads for Lucky Strikes and Chesterfields (for those who couldn’t manage rolling their own) also showed up. Smaller ads for long-gone brands such as 111’s and Tuxedos were also running.

Already in 1916, the new Proctor’s Grand Theater in Albany was running promotional pieces in The Enterprise, describing its vaudeville and movie schedule and noting that there was smoking allowed on the balcony. Movies had begun showing actors and actresses smoking cigarettes as early as 1909.

Cigs go to war

Then, in 1917, the United States entered World War I, landing American troops in France. Call it corporate greed, devious manipulation, or clever merchandising, or all three, but Big Tobacco came up with a plan.

A big notice on The Enterprise front page in early October 1917 that caught everyone’s eye read, ”The Enterprise Tobacco Fund.” The notice informed Enterprise readers that, through the efforts of the newspaper, arrangements had been made with the American Tobacco Company to send 45 cents worth of tobacco to an American serviceman for only 25 cents.

Each man overseas would receive two packages of Lucky Strike cigarettes, three packages of Bull Durham tobacco, and four books of Tuxedo cigarette papers. A postcard was to be included in each package allowing the soldier to thank the donor.

Week after week, an illustration that had been supplied to the paper appeared on the front page with a list of that week’s patriotic donors and the amounts given. Even the pupils of Altamont’s third and fourth grades sent in 25 cents. The campaign ran until May 1, 1918 collecting at total of $133.50. After that date, the government supplied tobacco to the troops.

Some anti-smoking advocates were outraged by the Tobacco Fund, bombarding the editor with angry letters. He responded, “To a man who has smoked tobacco all his life, and who has just gone through a drive on the battlefield, a tract on the morals of smoking would be of little solace.”

No mention was made of the thousands who were becoming addicted to tobacco for the first time. Readers were then asked, “Can’t you imagine the solace it must be to a man to draw long puffs of delicious smoke, whose taste and fragrant smell comes to say to him — Remember America — remember home … .”

In December 1918, a postcard that had been included in one of The Enterprise’s smoke kits was returned with the message, “Thank you for the cigarettes I received here in France. I certainly enjoyed a good smoke.

By 1920, American smoking habits had changed. The cigarette had become socially acceptable; it was convenient for a quick smoke and was cheap. Post-war ads of Bull Durham tobacco claimed you could roll 50 cigarettes from one pouch of Bull Durham tobacco. Local businesses advertised cigarettes as inexpensively as 13 cents a pack.

In 1964, when the Surgeon General’s Report on Smoking and Health was issued 44 percent of Americans were smokers.