Early radio days: Schenectady’s WGY was a pioneer and local families loved to listen

— Photo from the Guilderland Historical Society

St. Mark’s Lutheran Church, dedicated in 1872, was located on Guilderland Center’s Main Street. Several times a year, it was the scene of the dinner where a radio broadcast was the draw to bring in a large crowd. Today the church is Centre Point Church.

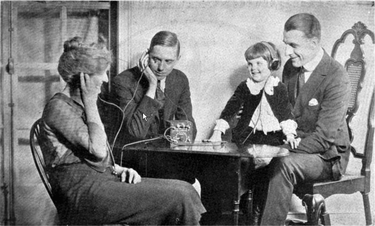

— Radio World Magazine, 1922

From a 1922 advertisement for Freed-Eisemann radios, an American family listens to a crystal radio. Since Crystal sets work off the power received from radio waves, they are not strong enough to power loudspeakers. Therefore the family members each wear earphones, the mother and father sharing a pair.

Radio first became a reality for the general public in November 1920 when Westinghouse station KDKA in Pittsburgh went on the air; its first broadcast was the news of Warren G. Harding’s electoral victory in that year’s presidential race.

General Electric in conjunction with the Radio Corporation of America launched Schenectady’s WGY in February 1922. Bitter competition existed between the two corporations, each intent on cornering the radio market to sell equipment to the millions of people eager to listen to this exciting new form of entertainment

Eventually GE and RCA made an agreement with Westinghouse to take over Westinghouse’s superior wireless patents in return for General Electric stock.

Having a powerful radio station nearby was the incentive for Guilderland residents to join in the national craze for radio. The Altamont Enterprise, recognizing local interest in the novelty, quickly added WGY’s weekly schedule to its pages.

Soon after, when the editor queried readers on the schedule’s value, he got a quick positive response, making it clear they appreciated knowing what was on the air that week. One Altamont listener felt, “It’s worth the price of The Enterprise to have this feature every week.”

The Guilderland Center columnist noted, “So many have installed radio outfits in their homes, and are glad indeed of the convenience of the weekly program. This is indeed an attractive feature of The Enterprise. Thank you, Mr. Editor.”

The popularity of radio spread so rapidly across the country that, by the end of 1922, WGY was one of almost 350 stations. Americans spent $60 million on radios and radio parts in 1922 and, by 1924, sales reached $358 million.

Radio purchasers were sometimes mentioned in local columns. Guilderland Center’s John J. Mann and Earl House, Altamont’s Walter Gaige, Guilderland’s Charles DeCoursey, or Dunnsville’s Charles Crounse and Jacob Becker, all installed radios along with the many others who were nameless.

The women of Altamont’s Colony Club devoted one of their sessions to the “up-to-date” topic of radio with presentation of talks on the history of radio and the topic “forecasts on broadcasts.” Entrepreneurs jumped on the bandwagon and began selling radios and radio parts and accessories, often advertising in The Enterprise.

The Enterprise also installed radio equipment to enable the newspaper to keep the community informed of important breaking events. The 1922 World Series could be heard at the Enterprise office as well as at the Altamont Pharmacy.

The Enterprise “Village and Town” column explained that the sporting editor of the New York Herald would be at the Polo Grounds reporting the games by Western Union wire to WGY’s wireless station in Schenectady, which then would be broadcasting the action to its listeners.

At Christmas that year, The Enterprise planned to use the apparatus to tune into the Santa Claus talks scheduled to begin on WGY on Dec. 18.

Generous Dr. Cullen

Dr. Archie I. Cullen, Altamont’s family doctor for many years, was a serious radio buff affluent enough to indulge in his passion. “Village Notes” told of his wireless apparatus being damaged by gale winds, when six feet of one of his 60-foot masts blew off. The doctor assured folks it was easy to repair since the mast was constructed to be raised and lowered.

Generous with his equipment and expertise, Dr. Cullen several times provided radio entertainment for others. The big attraction at Guilderland Center’s St. Mark’s Lutheran Church’s 1922 Memorial Day dinner was not the chicken, but the opportunity to hear a WGY radio concert broadcast with Dr. Cullen’s equipment and loud speaking horn.

Three hundred and fifty people turned out including a big crowd from Altamont. A short article the next week titled “Radio Entertainment” describing the evening commented, “This is the first entertainment of the kind the church has ever given and the first of the kind that most people have ever had the privilege of listening to.”

On another occasion, Dr. Cullen and another man spent hours setting up his radio outfit to allow Sunday School youth from Altamont’s Reformed Church to hear a program of music and vocal selections and a talk. That same spring, the Altamont Alumni Banquet attendees ate their dinner to music thanks to Dr. Cullen’s “receiving outfit.”

Altamont’s Leo E. Westfall and Stanley Barton were among 300 radio enthusiasts who drove to Union College where they attended the Capital District Radio Convention and banquet. Included in the program was a trip through GE’s radio department. Lester Sharp of Parkers Corners went to work in GE’s radio department early in 1923.

Two types of early radios

Actually, how did early radios work? There were two types, neither of which needed an outside power source.

In 1922, the United States Bureau of Standards released a publication called “Construction and Operation of a Simple Homemade Radio Receiving Outfit” detailing how any handy person could put together an inexpensive crystal set from materials easily obtainable, allowing even those of relatively modest means to join listeners across the country. Less than $10 bought all the components.

The late Everett Rau shared his memories of owning and operating a crystal set in his boyhood. Many years before, scientists had discovered that a crystalline mineral such as galena could pick up radio waves.

Everett recalled that the crystal was the size of a kidney bean. He said that you placed it in a conductive container with a wire connected to it and a circular object — oatmeal containers were very popular for this — around which you wrapped anywhere from 100 to 300 feet of insulated copper wire.

An antenna was needed as well. Everett mentioned his brother ran a wire out of the house and put it up a tree, but he found his metal bed springs served the purpose just as well.

In order to actually hear the broadcasts, you had to listen through a set of earphones with a wire that ran to a pin in the crystal. In most cases, a crystal set was capable of picking up broadcasts only 25 to 30 miles away, but on occasion was able to bring in a station from quite a distance.

Those who were more affluent could purchase and have installed more expensive radios that operated on battery power. Headphones were required, but it was possible to purchase loudspeaker horns that projected the sound into a room.

The Albany Radio Corporation advertised, “We have sets for every purse and every purpose from $5 to $1,000.”

Recharging batteries was a necessity, which a Clarksville garage advertised it could do. Probably other local garages did as well. One reference said radio batteries were interchangeable with car batteries and could be recharged by switching batteries, but that couldn’t be confirmed.

A 1927 Sears catalog offered a variety of radios with one price cash and a higher one if bought on installment. One example was $59.95, or $9 monthly for $65.95. Perhaps the craze for radios was one of the earliest examples of American consumerism.

Programs varied: Music, news, drama

Tuning into WGY brought a variety of programs. Music was extremely popular, introducing many people to classical music not only locally, but all over the United States.

One WGY piano concert featured works by Chopin, Brahms, and Liszt. WGY had its own orchestra and sometimes broadcast concerts from outside its studio.

One in 1922 originated from Union College and another came from Chancellor’s Hall in Albany where a huge chorus sang to an audience including Governor Al Smith. Vocal music was performed by sopranos, baritones, and tenors.

One night there was popular music, a program of old favorites, including ”On the Sidewalks of New York” and “In the Gold Old Summertime” while the orchestra played “Turkey in the Straw” and “When You and I Were Young, Maggie.”

Drama was another important phase of programming with either the WGY Players performing or sometimes a local dramatic society was brought in. One evening, a troupe of Troy’s Masque Community Theatre put on “The Wolf.” The first year on the air, the WGY Players acted in 43 plays with titles like “The Traveling Salesman” and “The Great Divide.”

Local talent was also featured. Altamont pianist Miss Margaret Waterman made two appearances, generating letters of praise from states as far away as Kentucky, Iowa, and Montana. Magdalene Merritt, poet of the Helderbergs, read a children’s story she had written called “The Gnome of the Evil Eye.”

Educational specials brought intellectual topics to many people who had never gone beyond eighth grade or read a book. One week in January 1923, for example, there was exposure to Japan in an evening of travelogues and music, and another where a full-blooded Quiche Indian would speak in his native tongue. His spoken language had aided archeologists in interpreting Mayan hieroglyphics and the program included a talk about Mayan civilization.

Health reports, special programs for housewives, weather reports and crop prices for farmers, correct time and church services were all presented on the air. Protestant church services prevailed, but there was also a concert of Catholic Church music sung by a 75-member choir originating from Our Lady of Angels Church in Albany and a New Year’s service from Temple Beth Emeth.

One man wrote to WGY from Trumansburg, a small town near Ithaca, that the Sunday service from Trinity Lutheran Church in Albany had been a comfort to his dying father. WGY generated regular press releases like this, sending them out to local newspapers with the hope they would be reprinted.

Public service

Service to the public was another feature that stations wanted to promote.

WGY was in the middle of a news story that made national headlines in 1923 when the 6-year-old son of Dr. Alexanderson, GE’s famous engineer working the field of radio and later TV, was kidnapped.

With no clues or leads, police were stymied until a man living in a tiny town outside of Watertown in Jefferson County picked up a WGY broadcast on his crystal set discussing the case. He remembered renting a camp to a couple with a young boy. Becoming suspicious, he took his boat out to the camp and managed to get a look at the boy.

Seeing a photograph of the lad in the Syracuse paper, he knew that boy was the kidnapped child. He called the sheriff, the boy was rescued, and his kidnappers were under arrest.

The coming of radio broadcasting changed Guilderland and America by broadening the horizons of millions of people and creating a national audience. Because a crystal set was so inexpensive and listening in was free, lack of wealth was little handicap. The intelligent programming of radio’s very early days gave way to soap operas and Amos ’N’ Andy, but that was another decade.