Children in the early 20th Century: Life could be wonderful or tragic with so much depending on family finances, the health of parents, and good luck

— From the Guilderland Historical Society

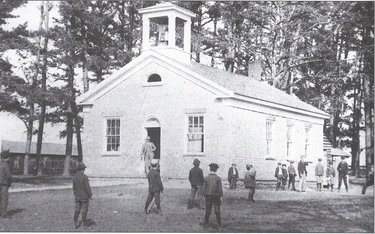

Boys at Guilderland Center’s Cobblestone School enjoyed an active game while their male teacher looked on from the doorway. Girls, who had little opportunity for active games, were probably observing from the sidelines. Both were expected to be quietly working at their seats during class time until it was their turn to go up to the teacher to orally recite their lesson.

— From the Guilderland Historical Society

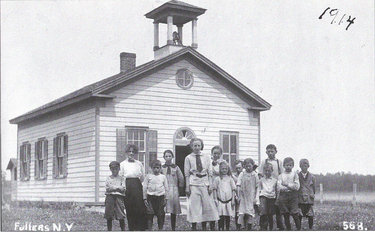

Anna Anthony posed with her students at the Fullers School. Teachers were expected to teach all grade levels with recitation and memorization considered an important part of a child’s education in the early 20th Century. Anthony, sixth from left, attended a summer session at the Oneonta Normal School after graduating from high school. That fall, at the age of 18, she was paid $15 weekly to teach at the Dunnsville School.

Life for rural Guilderland children in the early years of the 20th Century was still limited to travel by horse and wagon or train. Electricity and telephones were not yet available in their community, seeing a movie was a rare occurrence, and most children of that era had a very distinct memory of the first time they ever actually saw a car.

Children of 6 or 7 began attending one of Guilderland’s one-room common schools, although by then population growth in the communities of McKownville and Guilderland had led to the expansion of their schools to two rooms with a teacher in each room.

Altamont was by this time a Union Free School District, opening its impressive new building for grades 1 through 12 in 1902. Most of the town’s children never went beyond eighth grade, being competent enough with their common school education to farm or perform most of the jobs available at that time.

If they passed the seventh- and eighth-grade Regents (standardized tests are nothing new) to be awarded an eighth-grade diploma, there would be a special commencement ceremony.

In 1913, all eighth-graders who qualified from the “rural schools of the Town of Guilderland” graduated together at Guilderland ‘sPresbyterian Church. Quite an impressive ceremony, it opened with a prayer, followed by songs, declamations, readings, addresses, awarding of diplomas and a benediction — in all, 37 items. For parents it must have been a proud evening as each graduate had some part in what was a very lengthy program.

Altamont’s eighth-grade graduation took place in the Assembly Room of their new high school.

Special events

Certain special events of the school year relieved the monotony and were looked forward to with excitement, especially each school’s annual Christmas celebration when a special program was put on for the whole community.

Dunnsville school’s 1909 Christmas program brought out a standing-room-only crowd which heard songs, instrumental music, readings and recitations that were “carried out with intelligence and spirit,” bringing repeated cheers from the audience. The schoolroom had been decorated with a large Christmas tree in one corner.

Community Christmas gatherings and programs to which the public was invited would have gone on in all the schools in the town each year. The end-of-the-year school picnic was another tradition looked forward to by all the “scholars,” as they were always referred to in The Enterprise.

Challenges for teachers

Evaluating teachers? Regents results, the special events put on at school for the community, and their control in the classroom told people a great deal about their children’s teachers.

Discipline? Anna Anthony, as a new young teacher in Dunnsville, noticed all the children observing her closely one day and, when she eventually pulled open her desk drawer, there lay a dead mouse. A real rodent phobic, she managed to keep her cool, pick it up by the tail, drop it in the wastebasket and get on with her lesson.

But one young woman teacher at the Gardner Road School was overwhelmed by big, bad farm boys jumping out of the windows, falling off the recitation bench, in general creating chaos and preventing any learning from taking place. She was quickly replaced by a strong, tall Altamont High School senior boy who was given a temporary teaching certificate and a guarantee of his diploma to take her place and finish out the year.

Order was quickly restored when, at his arrival, he threatened to knock their heads together and legally could have done just that. Corporal punishment was the rule in those days in school or at home.

State mandates? All schools were expected to participate in an Arbor Day event in early May as mandated by the New York State Legislature. The state’s Department of Public Instruction issued suggestions for programs including recitations (memorization was considered a necessary skill in those days), songs, readings, and the planting of actual trees to beautify the schoolyard. Of course, the parents and public were invited to observe.

High school

Some of the children who received eighth-grade diplomas went on to high school. The roads being what they were at that time, commuting by rail was necessary at the student’s expense.

Fullers and Guilderland Center students rode the West Shore Railroad to attend Ravena High School, while those living along the D & H Railroad could go to Altamont High School. A few children in Guilderland and McKownville went into Albany for high school and, of course, the children who actually lived in Altamont had the easiest time.

Books were another expense paid for by the student so that many students at that time couldn’t afford to go to four years of high school. Since the course work in subjects such as Latin or plain geometry was meant for college preparation, a high school education wasn’t practical or necessary for them.

The number receiving diplomas from Altamont High the first decade the school was open ranged from three to 11 in a graduating class. Graduation ceremonies there included a baccalaureate service at one Altamont church and commencement at the other church.

Time with family

Children a century ago spent more time with family than in school. Locally, most boys and girls came from farm families who expected them to pitch in to share the work around the barn, fields, and farmhouse.

It was with family that most children attended one of Guilderland’s Protestant churches where there would be a special Children’s Day and Sunday school classes to provide religious instruction as well as offering Christmas celebrations and an annual picnic where the Sunday schools of several churches joined together for a really big gathering.

Sometimes children put on special programs for the public. McKownville Methodist “little folks” raised $24 in an entertainment program, offering choruses, solos, dialogues, recitations, and a Bo-peep drill. Families often attended church-sponsored suppers, ice-cream socials, and special evening programs as leisure activities.

Occasionally, special traveling entertainment came to town with a reduced-admission price for children, usually 10 cents. One year, families who could afford the price could have seen Jess Camp Rose offering a humorous entertainment at Guilderland’s Presbyterian Church, while later that autumn at Altamont’s Keenholts Hall “a collection of panoramic views of 80 of the choicest sights to be seen on a tour around the world accompanied by an intensely interesting description of each…” was on view.

Rarely during the first decade of the 20th Century that new entertainment phenomenon made an appearance in town when in 1903 at Altamont’s Reformed Church “The World’s Greatest Moving Picture Exhibition” offered a variety of scenes including President William McKinley’s funeral and the crack Empire State Express racing at 80 miles per hour.

Two years later, a similar program of brief scenes was shown at Keenholts Hall. Admission was 15 cents for a child. A circus visited Altamont some years and always the Altamont Fair was a big attraction.

Differences for boys and girls

Girls’ lives were more restricted than boys’ due to custom and to girls’ cumbersome clothes. Boys could roam the woods and fields, drop their drawers on hot summer days to cool off in a secluded stretch of one of the town’s creeks, or play baseball.

In 1909, they were even invited by the Grand Army of the Republic members to parade with them as an escort to Prospect Hill Memorial Day services. Mischief there was, especially on Halloween.

The Altamont village trustees publicly warned children damaging property that they would be “severely dealt with,” but that didn’t stop the “spooks” and “goblins” from making their rounds in Altamont.

Boys, being as adventurous as they were, couldn’t resist a building under construction, leading Master Stanley Crocker and some of his friends to explore the big new building Irving Lainhart was in the process of finishing off on Maple Avenue in Altamont.

Coming down off a scaffold, little Stanley ran into a plate glass window, smashing it and requiring several stitches to close up his badly bleeding head. That mishap was reported in The Enterprise, probably to his parents’ mortification — their names were listed also. Very likely, till all was said and done, something else beside Stanley’s head hurt!

One social feature of childhood reported on, often in great detail in The Enterprise, were the birthday parties, almost always for girls. The honoree and her invited guests were named, once as many as 21 little girls, with food such as the “bountiful luncheon” one mother provided.

Cake was served, games were played, prizes won, and a wonderful time was had by all, except the uninvited classmates. Most of this detailed information had to have been submitted by the birthday girls’ or the occasional birthday boys’ mothers!

Dark side

Sadly, there was also a dark side to childhood in that era. Death for infants and children came much more frequently, reflected in the columns of The Enterprise.

At J.F. Mynderse’s Altamont store, a parent could buy Chamberlain’s Colic, Cholera and Diarrhoea medicine to be used if your child is “not expected to live from one hour to another.”

The same issue of the paper informed its readers that Elizabeth, the 6-year-old daughter of Mr. and Mrs. Eugene Gardner, was suffering from cerebro spinal meningitis for a month and had shown slight improvement. Alas, the next week’s issue offered sympathy to the grieving parents after Elizabeth “fell asleep” and “all that loving hands could do was hers, but the hand of the grim messenger could not be staid.”

Another set of heartbroken parents put this poem in The Enterprise after the death of their little boy: “A bud the Gardener gave to us/ A pure and lovely child/ He gave it to our keeping/ To cherish undefiled/ But just as it was opening to the glory of the day/ Down came the Heavenly Gardener/ And took our bud away.”

Mumps, whooping cough, measles went through the schools, but most dreaded of the contagious diseases was the deadly diphtheria, killer of many youngsters. When there were “a few cases” in Guilderland’s school, it was closed down for several weeks and the writer of that community’s column sounded relieved when he noted Archie Siver, one of the victims, was out playing in the street again.

Scarlet fever could also be deadly. Mr. and Mrs. George Clute of Fullers lost their 17-year-old daughter, Alice, followed two weeks later by their 4-year-old, Nellie, both to scarlet fever.

Children’s lives were sometimes disrupted by the death of a parent.

Typhoid was another dread disease that struck both children and adults. Peter Weaver, at age 35, succumbed to typhoid, leaving behind a widow and two young children.

Camillo Compe, an Italian D & H employee, living at Meadowdale with his wife and child, was clearing snow from a switch when he was fatally struck by a train, leaving his wife and child to face a bleak future.

Losing a parent could be a tragic event for a child because often the surviving parent had difficulty caring for a family without a spouse. Many times, children were parceled out to various extended family members or the surviving family members had to move in with relatives.

Women faced financial difficulties with few ways to earn money in those days and men needed someone to run the house, a very labor-intensive operation at that time.

Illness and accidents carried off many young parents, but most in Guilderland seemed to have extended family to help out, unlike other unfortunates in Albany County who ended up in the County Almshouse.

The saddest case in Guilderland was the 4-year-old from Sloans (Guilderland), an illegitimate child whose mother was judged “depraved” and who was placed in the Albany County Orphan Asylum. This information with actual names was listed in the 1906 Journal of the Board of Supervisors.

Life for a child in those simple days could be wonderful or tragic with so much depending on family finances, the health of parents, and good luck. While a child’s life is so different today, in those respects nothing has changed.