The Kushaqua: Colonel Church’s ‘mammoth hostelry’ rises on the shoulder of the Helderbergs

— From the Library of Congress

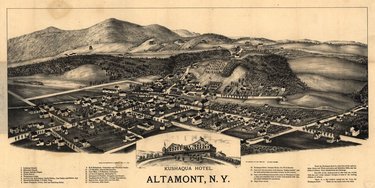

This early artist sketch of the Kushaqua paired with a panoramic view of Altamont illustrated the hotel when first opened. Helderberg Avenue is visible going up a steep incline, creating difficulties first in construction and after the hotel’s opening in shuttling guests and luggage from the D & H depot to the hotel.

Perhaps it was the influence of the comments of an 1881 Albany Evening Journal writer who claimed, “Tourists and summer boarders have flooded to the Helderbergs,” where local homes and hotels were “crowded to their utmost capacity.” It was a puzzle to him why no enterprising man had erected a summer hotel on such a “splendid site” in the hills, noting that wealthy Albanians had already begun building summer cottages in this beautiful, healthy location, easily reached by a short train ride from Albany.

Col. Walter S. Church, no stranger to the Helderbergs, seized the opportunity to be that man, taking on the project of erecting a fine resort hotel designed to appeal to an affluent crowd. In 1885, construction began on the crest of the escarpment overlooking the village of Knowersvillle, while below the hill curious locals followed periodic reports about what was initially referred to as “Colonel Church’s boarding house.”

His name had become linked to the area decades earlier when in 1853 he purchased leases to farms in the Hilltowns and surrounding area from the Van Rensselaer estate, planning to profit from dunning tenant farmers to pay both back and current rents. Over the next 32 years, through endless court cases and severe law enforcement by a succession of sheriffs and the New York State National Guard, he aroused the enmity of local farmers.

Anti-rent agitation ran high, but Church, a forerunner of the modern lobbyist, both forestalled any proposed anti-rent legislation at the Capitol and influenced the outcome of court cases by royally entertaining legislators and judges at his Albany home. Now he turned to creating a luxury resort to be called the Kushaqua, not only to be profitable, but probably to be his monument.

Building big

Construction of the hotel began in the autumn of 1885 when workmen began excavating the foundation on what had been farmland. Reports circulated that Church was building a three-story, 40-by-60-foot building. Excavation was complete by December and foundation work would begin, using the barrels of cement and carloads of sand that came through the D & H depot.

Hauling construction materials up steep Helderberg Avenue, the only road to the top at that time, was a major project in itself. By January 1886, the foundation was laid. Huge quantities of lumber had been shipped in and, as the structure neared rough completion, the windows arrived.

Spring brought Col. Church, accompanied by surveyors, to plot the location of a reservoir, using nearby streams and springs to supply hotel needs. Around this time, The Enterprise reported the colonel was expanding the size of the yet-unopened hotel an additional 84 feet because the original guest rooms were already booked. Within the walls of his new hotel, he had included parts of the original early 19th-Century farmhouse that had stood on the site.

Next Church secured an agreement with the Hudson River Telephone Company, paying the company to run a line out from Albany to his new hotel. At the time of the Enterprise report, the wire had already been strung out to Guilderland with the intention of running it out the turnpike to Dunnsville and then over to Knowersville.

Simultaneously, the two Knowersville hotels installed telephones as well. “Hello, hello!” was first heard in Knowersville when the Albany County Clerk called Church at his soon-to-be-opened hotel, according to a report in the Albany Argus.

Whatever amount Col. Church paid the phone company to run lines out to his hotel was repaid many times over three years later when fire was discovered in the hotel kitchen with smoke beginning to pour out the north wing windows. A hurried telephone message for help to Altamont (the village’s name changed in November 1887) brought a crowd of volunteers racing up Helderberg Avenue to man a bucket brigade from the hotel reservoir. Discovery that the fire’s location had started near a bakery oven and was beneath the floor brought it under control by ripping up the floorboards and saturating it.

Diverse attractions

Vacationers arriving on opening day in mid-June 1886 found reception and dining rooms on the first floor along with private parlors, card and supply rooms, and a barber shop. After registering, they would have been shown to one of the more than 50 guest bedrooms on the second and third floors, advertised to have “absolutely perfect sanitation conveniences.” The cuisine “would tempt the most exacting.”

In the basement level could be found a billiard room, children’s and servants’ dining rooms, kitchen, and storerooms. Available to guests were facilities for croquet, lawn tennis, and bowling. At the time of the Kushuqua’s opening, The Enterprise noted, “We have no doubt that Colonel Church is sparing no expense in the fitting up of this mammoth hostelry, and we have no doubt it will be well patronized the coming season.”

In addition to its newness, the main attraction of a stay at the hotel was its spectacular setting at almost 1,000 feet elevation. Bringing refreshing, cooling, healthy breezes, the site provided sweeping views over to the new capitol and church spires of Albany, east to Vermont’s Green Mountains and toward Schenectady where snatches of the Mohawk River could be seen.

Conveniently located only a half-hour train ride from Albany, The hotel welcomed arriving guests at the depot with conveyances to transfer them up to the hotel, their luggage hauled behind by wagon.

Rest and recreation were the key aspects of resort experience in the 1880s and ’90s. Strolling or lounging on the piazza to see and be seen took up time each day.

It was important to have reports seen in Albany newspapers that someone as important as Governor David Bennett Hill and his secretary, prominent Albanian Colonel Wiliam Gorham Rice, were walking on the piazza at the Kushaqua to attract future patrons. Landscaped grounds had paths for walking about, lawn tennis and croquet for the younger set, and “rambles” on local country roads.

Evenings at the hotel brought entertainment, often “hops,” the name given to informal dances in those days, when an orchestra was brought in. There were private parties such as the one given by the young woman who arranged to have a hop for 50 of her friends who then dined on an “elegant spread” afterward.

Guests seemed to greatly enjoy participating in entertaining themselves and were delighted to see their names reported in the Albany papers. One woman sang a selection of sacred music “most exquisitely rendered.”

Another evening, guests presented a series of “tableaux vivant” with people posing in costume to form a living picture such as the “bachelor’s reverie” displaying a “succession of really beautiful girls hovering in fascinating spirit form over a young man, presumably in a state of mental inertia;” while the “cabbage patch” proved to be a “galaxy of maidens peering through green paper tissue haloes,” etc. For this event, local people were invited up from the village.

An elocutionist gave readings and ladies performed charades, two more samples of the types of activities found at a resort hotel of the era. On occasion, an outside group such as the Knowersville Band was invited to perform. The Albany Evening Journal described life at the hotel one summer as “quite gay” with “entertainments of a high order.”

Newspaper reports told of nothing but success for the hotel. After the Kushaqua’s first season, The Enterprise claimed it was a “decided hit” certain to be one of the “most frequented resorts in the country in the future.”

The Albany Evening Journal reported in 1888 that the hotel had “unprecedented success the whole season.” A year later, a cool, wet summer didn’t seem to affect the visitors to the Kushaqua, which had its most successful season. Things always seemed to be going well at the Kushaqua.

Money pit

Yet in December 1890, after a short illness, Col. Church died, bankrupted by the overwhelming expenses of constructing and running the huge hotel. Resorts such as Saratoga, Lake George, and even Round Lake received much more coverage in the Albany newspapers and provided many more attractions than the Kushaqua.

Leased the next year by the Church estate to two New York City hotel keepers, additional money was invested in the building when steam heat was installed. In spite of the improvement, their venture failed and in 1892 the hotel was sold at a huge loss.

Unfortunately, Church underestimated the financial drain when, back in 1885, he was quoted as saying to a friend, “I don’t know I have gone in too strong, but I guess I can make a go of it.”

The hotel’s purchaser was Dr. F.J.H. Merrill of Albany who intended to use the building and surrounding grounds as his summer cottage. He paid $15,250 for the hotel, outbuildings, and property that had cost Col. Church between $60,000 and $75,000 (estimates ranged as high as $100,000). The hotel furniture was removed and shipped to Albany for auction.

Dr. Merrill, the director of the New York State Museum, was a geologist who shortly after was named State Geologist. Immediately, Merrill began making improvements to transform the hotel into a comfortable country home.

Employing almost 25 men at one point to make repairs, he added a new kitchen and laundry while the interior was rearranged for a reception room or hall through the center. Most of the old house that Church had kept within the hotel walls was removed.

At the same time, the large addition Church had added for the accommodation of hotel workers and a laundry was torn down. Merrill also ran the farm that was part of the property, even entering animals at the Altamont Fair.

Additional purchases of land were added to the property and cottages built with plans to rent them out to summer vacationers. The Merrills retained the former name Kushaqua for their summer “cottage.”

Similar to other residents of Altamont’s summer colony, the Merrills sometimes entertained on a scale unlike the locals. On one occasion, a trainload of Albanians arrived in Altamont, were transported up to Merrill’s cottage for a tea party. Most of the guests returned to the city after the refreshments, but a select group remained on for dancing to an orchestra. Governor Benjamin Barker and his wife were guests on another occasion.

Professor Merrill’s ownership of the Kushaqua suffered the same fate as Col. Church’s — their wonderful summer home and estate had become a money pit. The autumn of 1902 brought the announcement that it had been leased by H.J. Smith to be operated in the future as the Helderberg Inn.

Editor’s note: The saga of the Kushaqua will be continued in Mary Ellen Johnson’s next column.