The precise locations of the caves referred to in this column have been left deliberately vague to protect both the caves and inexperienced persons who might wish to enter them. Those interested in local cave exploration are urged to check out the website of the Northeast Cave Conservancy — www.necaveconservancy.org — and to consider a cave trip tailored to their abilities during the period between May 1 and Sept. 30 when the caves are open for visitors.

One might — in a whimsical moment — regard it as “The Spelean Archipelago.”

Though sport- and scientific-cavers have long frowned upon the term “spelunker,” the noun “speleology” — the scientific name for the study of caves, derived from “spelaion,” the Greek word for a cave — and the adjective “speleological” have long become standard usage.

Across the northeastern United States, preserves in karst areas dot the map, ranging in size from a single acre to hundreds — “karst” being the term for a region of limestone or marble bedrock containing caves. They are owned and/or managed by two organizations known as the Northeast Cave Conservancy, which recently celebrated its 40th anniversary, and the National Speleological Society — commonly referred to respectively as “the NCC” and “the NSS.”

The preserves protect numerous caves, the watersheds they involve, the unique life within them, and the classic karst surface features such as sinkholes, disappearing streams, and springs. Many local cavers are members of both organizations, the websites of which detail the history and geology of the various preserves.

From May through September, the NCC also offers instructions on access to the caves for the qualified public. From Oct. 1 to the end of April, many Northeastern caves — and all of those under the ownership or management of the NCC and NSS — are closed to protect the caves’ bat populations, which in recent years have been ravaged by the insidious disease known as “White Nose Syndrome,” or “WNS.”

Commercial caves such as Howe Caverns and a number of privately-owned caves that do not harbor bats remain open; however, winter has never been a very popular time for sport caving except for the most dedicated cavers, given the fact that Northeast caves are almost by definition very wet, and slogging through snow in sub-freezing temperatures to and from the caves can be extraordinarily miserable.

The National Speleological Society was founded in 1941 by a small but dedicated group of cave explorers and since has grown to become an international organization with thousands of members. In the Northeast, the NSS owns three Schoharie County cave preserves: Schoharie Caverns, the Gage Preserve, and McFails Cave, the most extensive in the Northeast. All three properties were donated to the NSS by generous patrons and have been maintained over the years by dedicated volunteers.

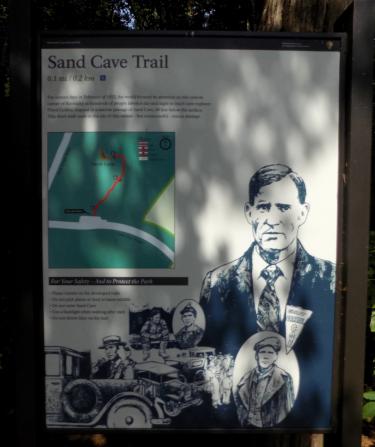

Knox Cave tragedy leads to stewardship

Yet the NCC was born as the final result of a tragic winter caving accident in 1975.

In March of that year, several students from the State University of New York Outing Club were attempting to enter Knox Cave through its ice-encrusted sinkhole.

The cave near the hamlet of Knox had sporadically been run as a commercial operation like Howe and Secret Caverns in Cobleskill, most famously under the ownership of Delevan C. Robinson and his wife, Ada. In the mid-20th Century, the couple were responsible for the building of an elaborate staircase offering access to the cave, which lies over 100 feet underground, and for constructing walkways and installing lighting for tourists.

D.C. seems to have had what the Irish call “the gift of blarney,” and some of his descriptions of the cave and its extent were — to put it gently — fanciful. But the cave features both large, easily-accessed passageways and more challenging sections that require stamina and sometimes ropework of explorers, and it has attracted serious cavers for many generations as well as tourists during the relatively brief periods when it was commercialized.

The Robinsons also built a large roller rink adjacent to the cave’s entrance sinkhole, which for a while in the 1940s and 1950s was the scene of skating parties and country dances. It seems to have formed a center of social life for the Hilltowns in the days when not many hardworking Helderberg folks could afford the time or the money to travel to nearby cities for entertainment.

But following D.C.’s death in 1961, commercial operation of the cave ended for the last time though sport cavers and scientists continued to gain access to Knox Cave with the kind permission of D.C.’s widow until she died in 1964.

Some time in the mid-1960s, the largely abandoned property was purchased by a Long Island corporation called “Organa Industries,” which announced its intention to restore the cave and dig out a boulder-choked sinkhole adjacent to its classic entrance to allow a through trip. But Organa Industries went belly-up and the restorations never took place.

Old-timers in the Knox area may remember the huge steam shovel that stood for years in the field next to the commercial entrance but it seems never to have been employed in digging the clogged sinkhole and it eventually collapsed into a rusty pile of warped metal and cables.

The result was that access to Knox Cave was without any sort of control; in the years that followed, the staircase and the walkways deteriorated and the lighting system and many of the cave’s natural decorations were vandalized and the skating rink and the Robinsons’ 200-year-old farmhouse were torched.

Even the massive frozen waterfalls that formed in winter from drainage in the fields around the Knox sinkhole did not deter visitors from entering the cave. Sometimes the warmer (48-degree) air within the cave would melt a tight hole allowing access to the adventurous — or risk-takers — while at other times the even more foolhardy were rumored to be using sledge hammers to smash their way through the ice to gain entrance.

In any case, one day in March, 1975, although snow still covered the ground, the temperature rose to 50 degrees as a group of students from SUNY Albany tried to enter the cave. Runoff from the melting snow poured in a cascade behind the ice deposits and the result was that a massive block of ice broke away and came crashing down, killing one student and leaving another paralyzed from the neck down.

By that time, the cave and surrounding land had been sold for non-payment of taxes to a doctor from Schenectady. Fearing additional injuries and lawsuits, the doctor attempted to donate the cave to the National Speleological Society.

But the same fears caused the NSS to reject the offer and a group of cavers became concerned that the cave might be acquired by someone who would ban all exploration or even bulldoze its entrance sinkhole, effectively closing it permanently.

Thus, in 1978, three area men — Dr. Art Palmer, Robert Addis, and Jim Harbison — formed the Northeast Cave Conservancy as a not-for-profit corporation and Knox Cave has continued to be made available to qualified cavers. Over the years, subsequent exploration has added close to 1,000 feet of previously unknown passage to the map of Knox Cave and revealed another segment of passage yet to be connected to Knox known as Crossbones Cave.

And over the years, through purchase or donation, the Northeast Cave Conservancy has acquired a number of other parcels of land containing caves that are also well-known to explorers.

Caves galore

A western portion of the Helderberg Plateau known as Barton Hill in Schoharie County rises steeply above the Fox and Schoharie creeks. A standing joke among cavers is that the hill is hollow because of the numerous caves that underlie it.

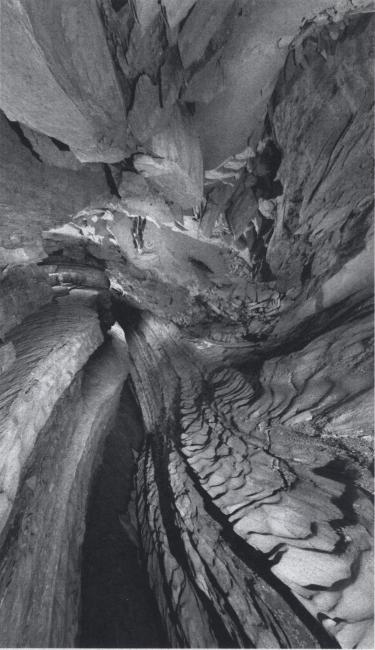

One large parcel of land owned by the NSS was donated by long-time caver and local attorney Jim Gage and contains Schoharie Caverns, which resembles a slot canyon; its entrance lies at the base of a limestone cliff on the edge of the plateau.

Schoharie Caverns consists of nearly half-a-mile of streamway featuring beautiful stalactites and stalagmites, which decades of visits by college outing clubs and other groups have left marvelously intact. A spartan cabin on the parcel is maintained by local cavers and is available for groups visiting Schoharie Caverns and other nearby cave preserves.

And there are many. The NSS also owns another large parcel of land on Barton Hill donated by Jim Gage and named in his honor; it contains Ball’s Cave, named after its 19th-Century landowner. Its vertical entrance lies in a heavily-wooded section of the hill and has drawn visitors for over 150 years.

The cave features immense rooms as well as low crawl ways, and a diminutive flooded segment of the cave known as the “Lost Passage” requires cavers to experience an “ear dip” to pass through it. (Do you really want to ask?)

Although there are a number of other known or suspected caves on Barton Hill not under the control of the NSS or NCC, Spider Cave was recently donated to the NCC by a local landowner. ts alluring entrance has been described as “Storybook,” but explorers have found that it is a very short story except for those intrepid enough to challenge its agonizingly tight, wet main passage that extends for over 1,000 miserable feet into the plateau. And those who enter its easily accessible first hundred-or-so feet will encounter hundreds of its eponymous creepy occupants scampering across the cave’s water-smoothed walls.

McFails is the jewel

Generally considered the “jewel in the crown” of northeast caves is McFails Cave on the Cobleskill Plateau. Its entrance is in a beautiful hemlock and hardwood forest pockmarked with gaping vertical sinkholes, some of which take voluminous quantities of water from time to time.

Only a short and very unpleasant segment of McFails was known until 1961 when some students from Cornell University plunged through a pool with just a few inches of airspace and discovered that the cave did not end at the uninviting pool.

Today the cave is known to be over seven miles in length, much of which consists of high canyons and large chambers beautifully decorated with calcite formations. But the cave can be treacherous: Entrance requires rappelling down seventy feet — in wet weather through a waterfall — and much of a cave trip involves constant immersion in a cold stream, making the wearing of a wetsuit a necessity.

The cave has been hydrologically connected to other caves on the plateau, meaning that water in them them has been traced to McFails. Thus the potential exists for a cave system some 26 miles in length — a fact likely to draw intrepid explorers for years to come.

Clarksville Cave is the best known

Undoubtedly the NCC-owned cave that is best known to the general public is Clarksville Cave, which has drawn visitors for well over 150 years. Groups from camps, schools, churches, and colleges regularly visit the cave between May 1 and Sept. 30.

Clarksville has three known entrances and lies beneath a hardwood forest laced with nature trails. While much of the cave consists of subway-tunnel size passages, more adventurous visitors are drawn to its tight — and wet — challenging sections that lead to pools and a picturesque waterfall.

Despite its easy accessibility and heavy traffic in summer months, much of the cave is relatively pristine and its numerous classic features both above and below ground make it a veritable textbook example of cave and karst geology.

Ominous Onesquethaw

Not far from the village of Clarksville is the lesser-known Onesquethaw Cave also owned by the NCC. Named for the stream that flows through the valley in which its entrance lies, its low, twisting passages are studded with fossils and its sometimes maze-like layout gives the cave a certain allure.

But Onesquethaw is not for the novice cave explorer and has long had a somewhat ominous reputation. It lies in a low area that is prone to flooding and in times of sudden heavy precipitation a roaring stream enters the cave and can fill its passages to the ceiling.

In 1991, a group of students from Syracuse University became briefly trapped in Onesquethaw when a torrential surge of water flooded the cave, setting off a massive rescue effort that drew news organizations and cave-rescue teams from all over the Northeast. The students had fortunately found a room with a high ceiling and were able to cling to the walls until the water levels finally dropped and allowed them to leave the cave.

As the students’ experience in Onesquethaw Cave demonstrates, the subterranean world demands respect of those who enter it. The Northeast Cave Conservancy and the National Speleological Society have not only managed to acquire and keep open many classic Northeastern caves for qualified visitors, they have educational and scientific components as well.

Through work with the general public as well as scientists and qualified students, ranging from grade school right up through university-level students, the organizations have helped to maintain and protect the resources of the world beneath our feet.

And the NCC and NSS are not alone. All across the 48 contiguous states and in Hawaii many hundreds of acres of karst lands and areas underlain by lava caves have been acquired and protected by organizations of dedicated cavers: a “spelean archipelago” indeed.

Could statehood be far behind?

Location:

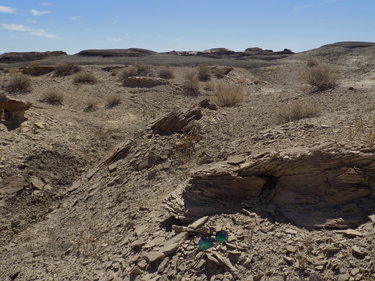

The Bisti/De-Na-Zin wilderness in the northwest corner of New Mexico is hot and dry for much of the year — when it is not bitter cold and dry — and it is far from the regions that are well-known to tourists such as those surrounding the cities of Santa Fe, Albuquerque, and Taos.

Even some of the draws for the more adventurous visitor — the “Sky City” Pueblo called Acoma, the stunning ancient Anasazi ruins of Chaco Canyon, and artist Georgia O’Keefe’s beloved Ghost Ranch — are far better known and more accessible than the Bisti/De-Na-Zin Badlands. Perhaps due to a recent article with photographs in “New Mexico” magazine, the public has become more widely aware of the preserve but the location’s remoteness virtually guarantees that even on weekends hikers are likely to find few others venturing into the barren wilderness.

The term “badlands” was coined by non-geologists but has been appropriated by geologists to describe an area featuring an exceedingly arid climate and relatively soft bedrock that has eroded into hills and sometimes weird sculptured shapes called “hoodoos.” Practically nothing can grow in badlands and even creatures such as insects, lizards, and snakes may be rare.

The Badlands of South Dakota became a national park because of the particularly colorful strata — layers — found there but large stretches of the United States Southwest and many other places scattered across Earth’s surface are badlands in fact if not always in name.

Geologists have always had great interest in badlands because in such barren landscapes — unlike in the well-watered, forest-and-field-covered stretches of the Northeast — the underlying bedrock lies open to easy viewing, and, where wind, ice, and water have worked on the bedrock, researchers can see deeply into the strata to find hidden clues to ancient environments.

The Bisti/De-Na-Zin badlands lie southeast of Farmington, New Mexico. The words are Navajo; “Bisti” translates to something like “large area of shale hills,” which perfectly describes it. “De Na Zin” references falcons, seen occasionally in the wilderness area.

Its soft bedrock is mainly shale and mudstone interspersed with volcanic dust dating from the Cenozoic Era, the age of the dinosaurs. Its eroding hills and hoodoos have yielded numerous fossils of dinosaurs and other creatures that were their contemporaries as well as plants.

The strata that make up the bedrock contain varying amounts of minerals such as iron, carbon, magnesium, and quartz, which give them different colors: black, white, gray, purple, brown, and in some striking examples, bright rusty red. The strata were laid down in what in ancient times was a delta on the edge of the long-vanished Western Interior Seaway and the purple layers get their color from iron dissolved in the water.

While most of the brown strata are mudstone, the black strata are either shale containing decayed organic matter or soft coal; at some point in ancient times, the coal caught fire, possibly due to nearby volcanic activity. In any case, there is evidence that the fires burned underground for centuries, leaving behind a brilliantly red layer that erodes into piles of rust-colored sand and what appear to be crushed bricks.

An adventure

With some friends, I set off on a hike into the Bisti/De-Na-Zin badlands on a warm day in early June. Hikers are advised to carry a device with GPS or a compass as the preserve does not have marked trails and landmarks can be deceiving, but we did observe a line of abandoned telephone poles that ran close to the primitive parking area.

Fortunately, given the gentleness of the topography, the poles were visible from great distances, providing us with easily visible reference points as the mazes of gullies and hoodoos of Bisti would not be good places in which to lose one’s way.

We set off over a series of low hills made of crumbling soft coal — a lifeless wasteland that looked like a landscape of Mordor in Tolkien’s Lord of the Rings — an uninviting beginning to a hike that gave no clue to what lay beyond.

Soon we climbed up out of the coal-bearing strata and found ourselves among the eroded fragments of ancient sand dunes, showing characteristic structures called “cross-bedding,” evidence of deposits caused by shifting water currents. In such locations, paleontologists sometimes find the footprints of late-Mesozoic dinosaurs.

Our map showed a great cluster of hoodoos half a mile or so away and we set off in a southerly direction. Soon we came upon a series of garishly-striped hills into which were eroded steep, narrow gullies — miniature slot canyons formed by the region’s occasional but torrential floods. On higher ground now, we could look across a wide, broad valley into which the sediments eroded off the Bisti hills have been settling for millions of years.

There were domes and small mesas, wide arroyos and narrow gullies, towering hoodoos, balancing rocks, and small erosive features resembling tables, turtles, barstools, and weirdly organic-looking forms suggestive of creatures out of some scary fairytale.

We climbed to a vantage point, a low flat-topped hill from which we could look down into a bewildering maze in which many of these sculpted features were clustered together. Nearby, and scattered randomly, projecting from the baked ground beneath our feet were fossilized stumps of Mesozoic-age trees that might once have offered shade to a dinosaur.

Though the air temperature was only in the low 80s, the sun overhead shone out of a sky swept with high, feathery cirrus clouds; the air was clear but for the thin haze caused by one of the Southwest’s forest fires that have been frequent this year. Though the scene before us was not without a stark beauty, it also seemed absolutely barren of life — and yet, from time to time a dusty-colored lizard would scamper across our paths and there were a few parched-looking cactuses and other desert plants.

The Bisti wilderness is also home to a number of golden eagles, hawks, and falcons but the occasional birds we could see soaring on updrafts above the baking ground were too far away for identification. In Jeff Goldblum’s iconic phrase from Jurassic Park — “Life will find a way.”

Like Mars

Some photographs sent back recently by the National Aeronautics and Space Administration’s “Curiosity” rover, which is currently climbing through the terrain of Gale Crater near the equator of Mars have demonstrated that the Red Planet, too, has its badlands.

The first blurry photographs of Mars returned by the Mariner 4 spacecraft in 1965 appeared to show what Carl Sagan called “a dull, uninteresting landscape” — all sand dunes and flat deserts like “Tatooine” in the “Star Wars” films, but subsequent probes showed that by very bad luck Mariner had missed vast stretches of Mars with complex, fascinating landscapes, including a spectacular canyon seven times deeper and 10 times longer than our own Grand Canyon.

In addition, photos of dried stream beds and river channels hundreds of miles long proved that the planet once had enormous amounts of flowing water — an absolute necessity for life as we know it.

Gale Crater was created eons ago when an asteroid crashed into the surface and the subsequent rebound of the bedrock thrust up an enormous peak called Mount Sharpe. The Curiosity rover began exploring the crater in 2011 and early on in its mission it sent back a photograph of the upthrust bedrock that shows a startling resemblance to some of the layered, eroded hills of the Bisti badlands.

The hills in Gale Crater have been found to be made of bedrock resembling shales and sandstones, interspersed with layers of volcanic dust — very similar to those in the Bisti wilderness and providing clues to the ancient environment of Mars. Cruising around the floor of the ancient crater, Curiosity has also analyzed numbers of heavily eroded hoodoos composed of cross-bedded sandstone.

These are evidence that the great crater was once filled with salty water with shifting currents that deposited the sand that was later turned to stone. Elsewhere the rover has photographed channels filled with rounded pebbles, the beds of ancient streams that flowed across the surface.

Today the Martian atmosphere is far too thin and cold to allow liquid water to remain on the surface for long without evaporating or freezing. But just as the hills of badlands such as Bisti/De-Na-Zin give scientists clues to the ancient environments of Earth, the eerily similar hills of Gale Crater give insight into the ancient past of Mars, and what they show is far different from what was inferred in the 1960s from those first, blurry images of the Martian surface.

The planet’s landscape is anything but “dull and uninteresting” and evidence shows that in the distant past, Mars was a warmer, wetter world with a thick atmosphere, and featured extensive bodies of salty water as well as rivers. In such a world life could have flourished.

But the surface today is devoid of anything living, subjected endlessly to ultraviolet radiation from the sun because of Mars’s thin atmosphere, and not a blade of desert grass nor dusty, stunted shrub is visible in the blasted landscape.

Eerily, the thin clouds that appear in Curiosity’s photographs are almost identical to those above the Bisti/De-Na-Zin wilderness: wispy feathery cirrus clouds formed from crystals of water ice high in the Martian atmosphere.

But, unlike the milky blue sky above New Mexico, the sky on Mars is a dusty yellow from tiny dust particles suspended in the atmosphere high above the surface by the planet’s winds. Sampling that atmosphere, Curiosity not long ago made a tantalizing detection: The cyclical presence in the atmosphere of quantities of methane.

The colorless, odorless gas is easily destroyed by ultraviolet light, and the atmosphere of Mars today is far too thin to prevent its destruction, meaning that the gas must constantly be replaced. While methane can be emitted during volcanic activity, the giant shield volcanoes on Mars appear to have been inactive for millions of years.

But methane is also a common waste product of biologic activity. Curiosity has found that in the relatively warmer months in Gale Crater the amount of methane increases and then levels off and falls as the climate gets colder. The possibility that this could be indicative of the activity of sub-surface primitive organisms has thus arisen.

Though relatively benign by comparison, the harsh climate of the Bisti/De-Na-Zin wilderness supports the existence of a few hardy forms of plants and animals, while the environment of Mars today is hostile in the extreme to living things. The thin air contains almost no oxygen and the dry, bitterly cold, barren landscape is constantly blasted by lethal radiation from the sun.

But the fact that Mars in distant ages was apparently much friendlier to life — if life ever arose there — gives hope that a few hardy organisms might have found refuge in a warmer, wetter, protected environment underground. Life, after all, is well known for “finding a way.”

Location:

The engineering achievements of the ancients astound us: The vast size and precision of the Egyptian pyramids, the extraordinary aqueducts of the Romans, the incredible invention of Greek temples such as the Parthenon, the environmental challenges overcome by the people of Southeast Asia to build the Great Wall in China and Angkor Wat in Cambodia, the extensive waterworks and massive temples of the Maya and the Aztecs — all continue to amaze and enthrall in spite of our own achievements using modern technology.

It is no wonder that some today deride the ancient people with assertions that they could not have achieved what they did without help from Out There and continue to claim evidence of extraterrestrial intervention from the star Sirius or some civilization with its home on one of the stars in the belt of Orion.

But a scientist friend of mine put the whole situation into perspective with this observation: “These so-called ‘researchers’ are telling us that beings with the technology to fly faster than light across the universe visited Earth in the distant past — and spent their time here showing ancient people how to cut and pile up rocks? After a journey like that, wouldn’t it have been more productive to teach our ancestors how to make penicillin? Or instruct them in the generation of electricity and the building of computers? Or show them something as simple but essential as the wheel, which many of them did not have?”

It is a fact that the ancient people had brains as big and complex as ours today and when they wanted to do something badly enough, they often figured out ingenious ways to do it without help from E.T. And we moderns frequently stand in absolute awe of what they accomplished using technology that we all too frequently brand “primitive.”

Early in April, I flew to Peru with friends to visit some of the major sites of the Incas. Since we had very limited time, we had booked one of those hectic if-it’s-Tuesday-this-must-be-Cusco vacations, the result being that the whole trip now seems like something I dreamed and I look upon the photos I took with that did-I-really-go-there sense of wonder and confusion.

Bu,t if the confusion is genuine, so is the wonder: at the incredible beauty of the Andes Mountains rising above lush but intimidating jungle; at the clash of the Incan and Spanish civilizations that gave birth to the mestizo (“mixed”) culture of modern Peru; and at the astounding architecture of the Incan peoples over 500 years ago that resulted in the construction of citadels such as Machu Picchu and other “lost” cities.

We began our trip with a very brief stay in Lima, Peru’s vibrant capital city, built atop thick layers of unconsolidated river sediments washed down from the Andes over millennia — the consequent instability of which makes the city a dangerous place to be during an earthquake: a subject, perhaps, of a future Back Roads Geology column.

Early on our second day there, we boarded a plane for a short flight to Cusco — also spelled “Cuzco”— an ancient center of the Incan Empire situated at an elevation of 10,000 feet in the Andes. Spanish conquerors did a rather thorough job of destroying the Incas’ “pagan” buildings but in many places the colonial-era palaces and churches they raised were situated on those buildings’ foundations.

Cusco is today a sprawling city, overflowing with tourists even in what is considered its low season — but their presence has ignited the city’s economy and much of the Old City is one immense traffic jam. Coupled with the elevation, the exhaust from motor vehicles makes breathing a challenge for those who have not acclimatized — which included many people such as ourselves who were there only briefly as Cusco is the jumping-off point for visitors bound for Machu Picchu.

The chewing of leaves from the coca plant is supposed to aid in alleviating the effects of altitude, and it seemed as if every hotel and restaurant offered patrons huge bowls of the dried leaves that they were encouraged to chew, or cups of tea made from coca leaves. I found the leaves to have a rather unpleasant flavor and, though the tea served with sugar was slightly more agreeable, any effect that the coca is alleged to have eluded me.

Sacsayhuaman

Much of our one full afternoon in Cusco was spent at the ruins of one of the citadels of the ancient Incan emperors called “Sacsayhuaman,” sprawled atop a flat hill high above the city. Our guide laughingly informed us that, although the name is almost unpronounceable to anyone not fluent in the Incan language — still spoken by many inhabitants of Peru—saying “sexy woman” gives a fair approximation.

Levity aside, even in ruins, the site inspires admiration for its builders. A stronghold of Pachacutec, one of the last of the Incan emperors, the site consists today of a series of formidable stone walls and terraces covering many acres, cut from the plateau’s limestone bedrock.

Though it is difficult to envision what it looked like in the days before it was largely leveled by the Spanish conquistadors, shaping and moving the massive carved boulders that make up the foundations and walls of the various structures would challenge 21st-Century engineers. Some of these limestone blocks weight upwards of ninety tons.

The awareness that the Incan builders accomplished this work with muscle power and simple tools alone astounds. Not only are the seams between the boulders tight enough that a knife blade cannot fit into them, the individual boulders themselves are often not cubic or rectangular.

Some of the huge blocks have slightly curved sides and, instead of having eight corners, may have as many as 14 or 16, showing that they were shaped with consummate skill. Current archaeological theory is that these intricate, tight-fitting shapes made the buildings resistant to earthquakes, a constant danger in Peru’s seismically-active landscape.

And indeed — in Lima and Cusco and other Peruvian cities, Colonial-era churches and palaces that were built on the foundations of razed Incan buildings have ridden out tremors with considerably less damage than structures around them lacking such foundations. Of course, millennia earlier, the ancient Egyptians also moved immense blocks and fitted them with uncanny precision, but the huge stones with which the Giza Pyramids were constructed are cubic or rectangular and have just eight corners.

Sadly, besides the massive walls and terraces, little else remains at Sacsayhuaman to testify to the extraordinary engineering skills of the Incas.

Sacred Valley of the Incas

The next day, the sky was gray with low, scudding clouds, and early in the morning we embarked by van up over the mountains surrounding Cusco, headed for what is romantically named the Sacred Valley of the Incas.

Getting there first required a steep climb up narrow, twisting roads followed by a descent of several thousand feet, all the while passing through green, terraced fields in which men and women in traditional Andean dress labored among crops and herds of sheep and llamas — pronounced “yamas” in Peru.

Before starting the descent, we paused at an overlook that presented a heart-stopping view of the switchbacks plunging into the valley and our first look at the high Andes. As the sky was overcast, the view was sketchy — but far off through breaks in the clouds were glimpses of glaciers and jagged, snow-covered peaks rising out of the mists that hung on the precipitous green slopes: It seemed a vision of the Himalayas.

In the afternoon, we climbed the ruins of the enormous Inca citadel called Ollantaytambo, site of one of the few defeats suffered by the Spaniards as they fought their way through the Sacred Valley. Situated between two steep mountains, it consists of a residential area on the floor of the valley and a series of massive terraces like giant steps ascending one of the slopes, accessed only by two narrow stone staircases.

The terraces served both as gardens and fortifications, and atop the slope is a broad platform with a temple. It is not difficult to understand why the Spanish conquerors were unable to take the fortress: The defending Incas had gravity on their side and were able to rain down crushing boulders onto the invaders.

The platform sits atop precipitous cliffs dropping a hundred feet or more, and tightly fit into the tops of the cliffs are stone walls consisting of the characteristic enormous, meticulously-shaped boulders. Constructing the walls must have been a daunting challenge — one misstep on the part of the workers shaping and placing the boulders would have resulted in a deadly fall, undoubtedly accompanied by the thunderous collapse of sections of the wall as well.

Once again a visitor stands in awe of the Incas’ determination and skills.

Jungle journey

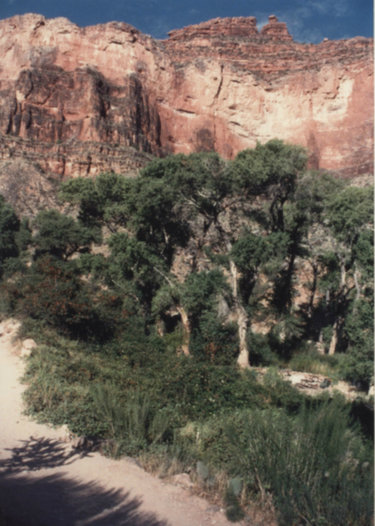

Early the next morning, we were deposited at the train station in the little town also called Ollantaytambo and we boarded the dome train that transports visitors through the jungles of the Sacred Valley to the village of Aguas Calientes, close to the citadel of Machu Picchu.

The 80-minute trip follows the ancient Inca Trail and the furiously-rushing Vilcanota River that downstream changes its name to the Urumbaba and eventually becomes a tributary to the Amazon.

The trip must be one of the most scenic train rides in the world. Heading toward Machu Picchu, on the right side of the cars passengers have a close-up view of the jungle which seems at any moment about to engulf the tracks.

It is a tangle of towering trees casting the floor into semi-darkness in which glimpses can be had of white, pink, and yellow orchids and other tropical flowers growing among shrubs and enormous ferns. But like giant entangling spider webs, vines thick and thin connect the trees and would make passage through the jungle a nightmare, even with machetes.

Occasionally visible through breaks in the foliage was the ancient Inca Trail that follows a narrow path through the jungle; it is a popular four-day hike for the adventurous visitor willing to challenge the biting insects and venomous snakes but in many places it was obvious that a hiker could be less than 50 feet from the train tracks or the trail itself and become hopelessly lost in the strangling vegetation.

Frequently there are foaming brooks and cascades pouring down from the high surrounding mountains, their waters bound for the Vilcanota and eventually joining the dark, meandering stretches of the Amazon.

And yet, despite the feeling generated of being in an endless, remote wilderness, periodically the train passes through areas on the far bank of the Vilcanota where archaeologists have cleared away the invading jungle and uncovered remote Inca settlements consisting of the characteristic terraces and foundations of dwellings, abandoned hundreds of years ago as the conquistadors marched ever deeper into the vastness of the Incan empire.

In other places, the jungle suddenly retreats and is replaced by a wide stretch of the valley floor that is being farmed or mined today by hardy descendants of the Incas; here the scene suddenly opens up to allow through the dome of the car breathtaking views of the high Andes: dark, craggy peaks in silhouette against the clouds or broad snowfields and glaciers gleaming in the brilliant sunlight, once more irresistibly evoking the landscapes of the Himalayas.

Ring of Fire

Shortly before noon, we arrived in the tiny picturesque village of Aguas Calientes — “hot waters” in translation. The village rises steeply above the eastern bank of the Vilcanota River, which descends energetically past the village in a series of roaring cascades and plunge pools.

A hot spring near the village has attracted bathers for hundreds of years. There are no volcanoes in the area, but the Andes Mountains rose — and continue to rise — as a result of the interaction of two of Earth’s major tectonic plates: the Nazca plate and the South American Plate, and the interface between them constitutes a section of the Pacific “Ring of Fire.”

The Nazca Plate takes up a large section of the Eastern Pacific Ocean and it is being pushed up against and subducting beneath the South American Plate; this causes the South American Plate to crumple, forming the Andes, but the friction caused by the subducting Nazca Plate melts parts of the crust and the molten rock rises to the surface and explodes in volcanoes. The presence of the hot springs in Aguas Calientes indicates the presence of molten rock not far beneath the surface.

In search of Vitcos

Immediately on leaving the train, we were escorted to a bus which takes visitors up a series of sharp and exposed switchbacks to the plateau on which Machu Picchu lies. It is a hair-raising ascent through the jungle with one 180-degree turn after another — and of course, there are no guard rails.

On some turns, passengers on one side of the bus or the other literally can see no road beneath them as they look out the windows but instead are staring straight down a plunge of hundreds of feet into the deep, rocky gorge of the Vilcanota River.

Along the way, the road frequently intersects one of several steep stone staircases that slice through the jungle and in ancient days offered the only access to Machu Picchu; these made the site virtually impregnable — even if the conquistadors had learned of its location — which they never did.

In fact, although rumors of its existence had been widespread for centuries, except for a few hardy farmers in the area, the rest of the world — including most Peruvians — remained unaware of its existence until 1911 when an expedition sponsored by Yale University and the National Geographic Society led by Hiram Bingham discovered it with the aid of some of those farmers.

Many explorers before him had been searching for the gold of the Incas that had not been appropriated by the conquistadors — and they had taken incredible amounts of the precious metal from Incan temples and shrines.

The interiors of the great cathedrals on the central squares of Cusco and Lima and other Peruvian cities are decorated with jaw-dropping quantities of gold, giving them a truly ethereal glow. But legends have persisted for hundreds of years that, as the Spanish conquerors swept through Peru, the forewarned Incas secreted much of their gold in places that have yet to be discovered — a powerful lure to adventurers even today.

However, Bingham and the Yale expedition were not looking for the vanished Incan gold: They were in search of Vitcos, the fortress that was considered to be the capital of the Incan empire.

Questioning occupants of one of the small villages scattered along the Vilcanota River, they learned that some of the farmers had been working ancient terraces on top of a nearby peak known as “Machu Picchu” — Incan for “old mountain.”

Machu Picchu

Ascending the peak by way of one of the ancient trails, Bingham and his crew came upon the hidden fortress. Though the jungle masked most of the magnificent site, the expedition cleared enough to be aware that they had made a major discovery. Today, with much of the vegetation cleared away, the magnificence of the site has been revealed.

Quarried from the granite bedrock of the mountain, the site sprawls over hundreds of acres, and there are still sections that lie under the suffocating jungle awaiting excavation. One of the most common igneous rocks on Earth, granite is frequently found in mountain ranges and makes up much of the bedrock of the continents.

Among its major constituents is the mineral feldspar, which can come in many colors ranging from gray or white to pink, rose, red, or purple. It is a very hard rock — harder by far than limestone — and not only did the Incas prize it as a decorative building stone but so did the Egyptians and other ancient cultures. Its hardness makes it difficult to work and inspires admiration for the people who carved it with such precision.

Today the site is believed to have been a retreat for the emperor Pachacutec, and everywhere are the foundations of private homes, temples, and what might have been palaces for the emperor and his retinue. These structures are situated on flat stretches of ground between the great terraces, which were used both for farming and for defense and, as in other Incan sites, are all interconnected by a series of steep stone steps.

Seeing them, one has the thought that the Incan people must have had exceptionally strong legs, accustomed as they were to climbing up or down constantly!

There are several springs in Machu Picchu and their waters were fed into channels that provided irrigation for crops in the terraces, drinking water, and fountains all over the site. But the terraces did not have to serve for defense as the conquistadors never discovered Machu Picchu — indeed, they probably never even knew it existed.

And, in any case, given the fact that the only access to the site is by way of the precipitous stone staircases that ascend from the Vilcanota River valley, an invasion or siege with the military technology available to the conquistadors would have been next to impossible.

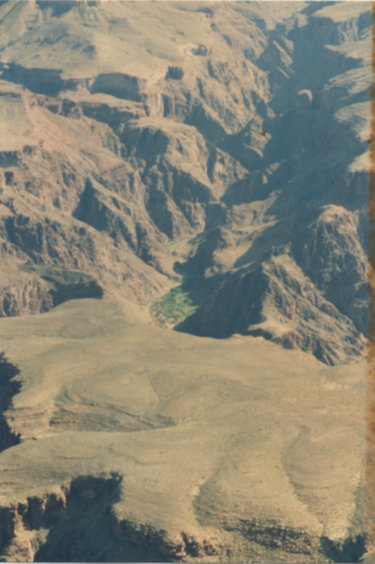

As impressive as Machu Picchu is for the engineering that went into its construction, it is undoubtedly its physical setting that has made it an item high on every traveler’s bucket list as well as a source of misguided mysticism.

The citadel is surrounded by high jungle-covered mountains with sheer granite cliffs plunging thousands of feet to the Vilcanota River valley, up and over which drift the mists which give the site its mystical appearance.

Moreover, draped in tropical vegetation a jagged peak — described in all the guidebooks as “iconic” — looms over the site just as the pyramids of the Maya and Aztecs and Egyptians towered over their cities. It is not surprising to learn that it is in fact named “Pyramid Mountain”; it features a vertiginous trail sliced from the granite to its summit where there is a small temple to the Sun, the focus of Incan cosmology. One could be forgiven for thinking that even a Wal-Mart built in such a setting would inspire awe.

Archeologists today estimate that, in its heyday, Machu Picchu could have been home to as many as 6,000 people and provided a refuge for the emperors from the Spanish invaders. Given its remoteness and the difficulty of accession, it is easy to believe that many of the ancient people must have lived out their entire lives in the city.

It had a moderate climate, a steady and abundant supply of water, fertile ground for growing crops, an endless supply of building stone, and views that are ever-changing and provide constant inspiration for the Incans’ religious connection with Creation.

Mysteries remain

And reports have begun to surface that in the vegetation-cloaked mountains surrounding Machu Picchu, explorers have in recent years uncovered evidence of two more “lost” Incan citadels — one that has four times the area of Machu Picchu and one with six times its area. Clearly, the dense jungles of the Peruvian Andes hold many secrets yet.

It is sad to realize that many visit Machu Picchu because they see it as having some New Age connection to extraterrestrials or crystal energy — a fact confirmed by the presence in the tiny village of Aguas Calientes of so many head shops, tattoo parlors, and psychics, and the drifting odor of marijuana.

For the fact remains that Machu Picchu and the other great citadels of the Incas with their massive, intricately-shaped building stones and their many other astonishing feats of engineering are monuments to human ingenuity: with the simplest of tools and sufficient determination, the ancient Incan peoples were capable of achievements that can inspire admiration and awe even amid the technological marvels of the 21st Century.

Location:

It is impossible to sleep.

Before we had crawled into our tent, we had noticed that the rocky outcrops around us were still warm, radiating the heat absorbed from the sun during the day. On top of that, there is hardly any breeze stirring, though we had read that cool, dense air from the North Rim of the Grand Canyon often sinks down to the river in the evenings, providing respite from the day’s high temperatures.

Not tonight.

The air is still and uncomfortably hot and dry. Some campers have their tent flaps open; others are simply sprawled out on the ground in their sleeping bags or on picnic tables, but my encounter with the rattlesnake on our hike down and warnings about scorpions have made me determined not to sleep without the protection of a screened tent around me.

In addition, I am being kept awake by the dryness of the air that is sapping our bodies’ moisture and making me thirsty. The Bright Angel Campground is fairly crowded and there is the nearly constant muffled sound of voices from people as restless as we are.

Undoubtedly adding to everyone’s discomfort are the words of the Park Ranger at the evening campfire: “Now I’m going to give you the bad news. You, ladies and gentlemen, have hiked to the bottom of the Grand Canyon, one of the deepest water-cut gorges on Earth. And tomorrow morning, you are going to have to haul your butts up and out of it!”

I had slept poorly the night before we had started our hike and the strain on our leg muscles of hiking steeply downhill coupled with dehydration requires a good night’s rest but it is obvious we are not going to get it, and sometime around 4 a.m., Steve says, “This is crazy. There is no way I am going to get any sleep. While it’s still dark let’s get moving.”

By the light of our headlamps, we load up our tent and poles in our backpacks and deliver them to the mule stable — we had discovered just before we attempted to retire for the night that for 50 bucks, the mules will haul our backpacks up to the South Rim, so we need only the light day packs we have brought and our canteens. To our surprise, the Phantom Ranch snack bar is open at that hour and we purchase a couple of trail lunches for the ascent.

As we leave the campground, the first faint light begins to glow in the east but we keep our headlamps on as we make our way over toward the river to avoid confronting snakes or scorpions. The sky brightens surprisingly fast and, by the time we reach the bridge over the Colorado River, there is sufficient light to walk without headlamps. The air now seems for the moment pleasantly cool and we are cheered by the thought that we may be able to get up and out of the Devil’s Corkscrew before the worst heat comes.

A moment to remember

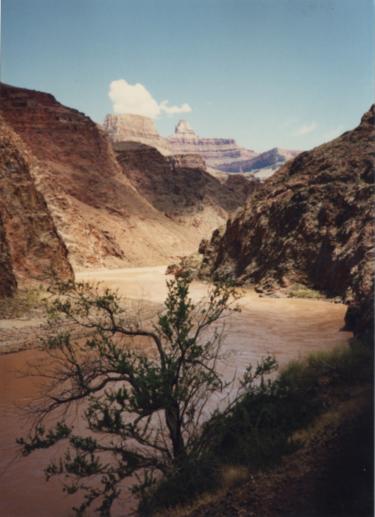

Just as we start to cross the bridge, dawn’s red sunlight hits the tops of the mesas and jagged buttes and pinnacles, making them look like glowing embers and we stop to take in the spectacular scene. Just a few yards beneath us, the turbulent currents of the muddy Colorado rumble over boulders in its bed — the only sound that breaks the stillness — and the bridge vibrates with the river’s power.

There is not another living soul in sight — it is as though we are the only two people in the canyon, a moment to remember all of our lives.

The trek back along the bank of the river somehow seems less of an ordeal than it had the previous day, perhaps because we know with every step the South Rim is closer. Along with our friends Rich and Teresa, we have made reservations for that night at the venerable El Tovar Lodge, which has a swimming pool, a highly-regarded dining room, and air-conditioning.

But between Bright Angel campground and the South Rim lie 4,500 feet of elevation gain over 10.3 miles of trail and those facts provide a reality check to the elation we have felt in our view from the bridge.

We arrive at the base of the Devil’s Corkscrew and we each guzzle close to a quart of water before we begin to climb. From below, the torturous twists and turns of the trail are not very obvious and we discover to our pleasure that the steep, stony trail is in some ways easier to ascend than it was to descend for the simple reason that gravity is not forcing us forward and down at awkward angles with each step. Also, at this early hour of the day — it is around 6 a.m. — much of the Corkscrew is in shadow, tucked as it is in its own side canyon.

We pass a few lone hikers headed down who have also taken advantage of the cool morning — they must have started their descent around 2 a.m. Oddly, except for exchanging hasty greetings, no one stops to chat — everyone hiking wants to get the Corkscrew behind them.

As we climb, we make occasional brief stops to let the muscles in our legs relax but the lure of getting back to Indian Gardens before the sun begins again to turn the Corkscrew into a furnace is irresistible. We are also pleased to discover that, with increasing altitude, the temperature is staying steady or perhaps even dropping.

This seems to energize us and within an hour we have reached the sign describing the Great Unconformity — the Corkscrew is now history. The green cottonwoods of Indian Gardens and the cool shade they offer seem a prize for our morning’s efforts and we take a break for water and snacks.

Intricate features revealed

Descending Bright Angel Trail, we were rewarded with the vast, panoramic views of the canyon with its stunningly sculptured towers of rock. But on the ascent our backs are to the long views much of the time and the intricate features of the various layers of sandstone and limestone are revealed.

The National Park Service has set up labelled displays of the fossils: There are trilobites and their fossilized trails, brachiopods — oyster-like shellfish — snails and fragments of crinoids, commonly known as sea-lilies. Incredible to think that hundreds of millions of years ago this bone-dry environment was from time to time under a warm, shallow sea dotted with reefs and islands like today’s Bahamas.

Yet in between the limestone strata are the various strata of sandstone, and these show thin laminated layers meeting each other at odd angles: features known as cross-bedding, representing petrified deposits of sand left there by ancient shifting winds. This tells of Earth’s surface cyclically heaving upward, causing prehistoric seas to retreat and turning the landscape into desert as it is once more today.

In many places, in the precipitous, far-off limestone cliffs there are dark cave openings that in times of unusually wet weather may even today gush water. Most are unexplored as it is appallingly dangerous to get to them: Explorers must either rappel down from hundreds of feet above the entrances or do challenging rock climbs from below.

The caves are very ancient features and the few that have been entered have yielded stalactites and stalagmites which have been radiometrically dated to over 7 million years ago. But were these caves here before the Grand Canyon formed or are they more recent? The answers are controversial and contradicting and are part of the centuries-long debate as to just how and just when the Grand Canyon came to be.

As we climb above Indian Gardens, we encounter increasing numbers of hikers, a few bound for Phantom Ranch and the campground, many for Plateau Point.

One young couple says, “We’re almost down to the river, aren’t we?” and we gently explain that they still have a long way to go. They have no idea what the Devil’s Corkscrew is and we realize then that they are not following a map.

In addition, the young man is wearing open-toed sandals and at the end of the hike is likely to have blisters on his feet the size of golf balls. But rather than trying to scare them with dire warnings, we tactfully suggest that, given their inexperience and the rising temperatures as they descend, they might want to turn around at Plateau Point — which, to be sure, is far deeper into the canyon than most visitors go.

They seem grateful for the advice and head off downward energetically. As the saying goes, “Experience is the best teacher.”

End in sight

It is now late morning and we are approaching the last switchbacks of the trail before we reach the South Rim. We are dusty and sweaty and obviously look tired but are exhilarated to see the end of the challenge so close now.

The temperature has continued to remain steady as we climb and now stands in the low 70s — fine for hiking. This section of the trail is crowded with visitors, many with little kids, doing just as my family did those many years ago — descending a few hundred feet on the Bright Angel Trail to get a feeling for being in the canyon instead of just looking at it, as it were, from the outside.

A ranger we talk to later informs us that a survey has revealed that the average time visitors actually spend looking at the Grand Canyon is a minuscule 12 minutes before they head off to the souvenir shops, the game rooms, and swimming pools of the hotels, or one of the numerous food services. To me, this is comparable to someone’s standing on a bluff on the New Jersey side of the Hudson River, taking a couple of quick selfies with the skyscrapers of Manhattan in the background, and texting friends that they have been to New York City.

Following directions in our trail guide, just before we reach the rim we take a look into an inconspicuous hollow above the trail and there we see pictographs left by the Anasazi or one of the other ancient peoples who have made their ways into the canyon. A handprint and figures of deer and other animals appear in red paint, surprisingly well-preserved in this dry environment even though vandals have managed to find and mar some of them.

Their presence emphasizes the long history of the trail and evokes admiration for people with primitive equipment who must have been motivated by the same sense of awe and wonder that lures hikers today.

As we arrive at the rim, several people come over to ask if we have come up from the bottom and seem impressed when we answer in the affirmative. One elderly man says, “It must be a great experience,” and sounds wistful.

“Yes, yes it is,” is our response. “It really is.”

Not particularly eloquent, of course — but sometimes simple words convey the most truth.

In any case, no question we hear matches what a park ranger tells us he was asked upon emerging from one of his many trips into and out of the canyon. A middle-aged couple approached him — dusty and sweating and sunburned like ourselves — and asked if he had been to the bottom, and when he replied that he had, the woman asked, “Is there anything down there?”

As the saying goes: If you have to ask a question like that, you would never understand the answer.

We head for our hotel, a hot shower, a good dinner with a celebratory glass of wine, and a well-deserved night in a real bed. And, as was true of so many before us who have descended into the depths of the Grand Canyon, we dream.

Location:

Everyone remembers the first time they see the Grand Canyon.

Mine came over half a century ago when I was 14 and it is still burned into my memory along with my first sight of the Giza pyramids; my first close-up look at an erupting volcano; and my first view — from a hillside fragrant with pine resin called The Pnyx — of the Parthenon at night glowing in subdued flood lamps above the noisy, twinkling streets of Athens like a vision from myth.

My family was on a cross-country trip and we had driven up from Phoenix, Arizona that day. The first half of the drive had been blisteringly hot.

Cars did not have air-conditioning in those days and my mother and father had shared the driving, but even today it is a tiring trip, passing first through forests of giant saguaro cactuses, then ascending through cool mountain meadows where elk wander and, skirting Flagstaff, heading into high desert where the apparently endless flat terrain gives no hint of the awe-inducing landscape that lies just to the north.

We arrived around 10 at night at the venerable Bright Angel Lodge where my parents had reserved a cabin that was close to the South Rim of the canyon. They were both looking forward to getting a shower and a good night’s sleep but I remember being appalled that they did not first want to see the canyon. Assured by the hotel clerk that there was a safe viewing deck right behind the main lodge, I took off on my own, promising to join the family at our cabin in 15 minutes.

The clerk directed me to a doorway that led out onto the deck and it took a few moments for my eyes to get accustomed to the darkness. The bright first-quarter moon had risen in the eastern sky and slowly there emerged from the dark vastness the silhouettes of great craggy pinnacles and towers and though in the dark it was impossible to gauge size or distance, I could tell what lay before me were massive structures stretching to the horizon.

Far, far below was what appeared to be a thin, meandering line drawn in softly luminous ink — my first glimpse of the far-away Colorado River. A mild breeze was rising from the depths, carrying with it the fragrance of sage and other desert plants, an odor I have heard described as “desert incense.”

An eerie howl was the only sound that broke the overwhelming stillness — perhaps somebody’s dog, though at 14 I was sure I was hearing a coyote. However — I have since spent enough time in the Southwest to realize that it probably was a coyote as these critters are ubiquitous in the deserts.

At any rate, with that unearthly sound, I suddenly became aware that a dark, precipitous abyss lay before me and for a moment I steadied myself against the retaining wall that surrounded the deck as I was overcome with the vertiginous sensation that I was about to be pulled over the side. I remember withdrawing into the light of the lobby of the lodge where everything was on a more human scale and running to our cabin.

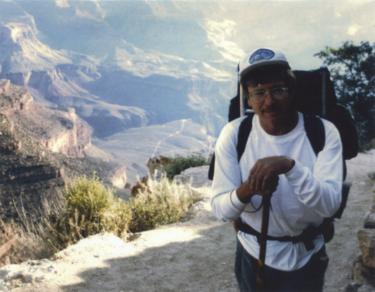

The next morning, my father took my sister and me on a short hike down the iconic Bright Angel Trail that leads down to the Colorado River. We were on a tight schedule and had to meet relatives in Los Angeles in two days but Dad wanted us to have the experience of being down in the canyon instead of just seeing it from the top.

My mother declined and opted for a walk on one of the paths that run along the canyon rim, meandering through desert plants and offering dizzying views of the spectacularly colorful rock formations below.

My recollection is that we walked not more than a half-mile down the steep, dusty trail and foolishly had not brought any water. The South Rim is at 7,000 feet and tends to be fairly cool even in summer, but one of the great misconceptions novice hikers entertain — and we were definitely novices! — is that temperatures down in the Canyon are cooler than at the rim. (Fact: Temperatures tend to decrease with increasing elevation, and increase with decreasing elevation, a lesson I certainly knew many years later but did not appreciate until I hiked with a friend all the way to the bottom.)

I had been a rock collector since I was around 5 years of age but at 14 I knew very little about geology though I had read in a guidebook that the canyon had been cut by the Colorado River over millions of years. I was fascinated by the fact that the rocks were in layers of many different colors even if I had no idea why — Dad probably tried to explain that to me, but who remembers lessons from when you are 14?

We probably descended 500 feet or so below the canyon rim — following, as it turns out, a route first used by the ancestral pueblo people long known to history as the Anasazi. Beautiful as the scenery was, I remember being surrounded by the massive stone forms and experiencing again the feeling of vertigo as we gazed off into the immense gulfs of the canyon.

It was with some relief that my father told us that we had to head back up to meet Mom and take a drive along the rim to see more of the awesome scenery before we left on the next leg of our drive west. In all, we spent less than 24 hours at the canyon — fairly typical for the average tourist even today.

But that brief descent of the Bright Angel Trail remained lodged in my memory as one of the highlights — albeit a bit scary — of our California trip. And the sight of the far-away bottom of the canyon and that narrow-seeming Colorado River surely fired my determination to come back someday and hike all the way down.

Return to the canyon

It was many years later that I returned to the Grand Canyon (rather more than fully grown!) but this time with several friends: a fellow hiker named Steve with whom I planned to hike to the bottom and tent overnight in the Bright Angel Campground near legendary Phantom Ranch, and an old high school buddy named Rich and his wife who were going to do the mule ride down to the bottom and stay in one of the rustic (but air-conditioned) cabins at the Ranch.

We arrived on a deceptively cool August evening after a long drive from New Mexico and spent the night before our trek in the park campground. This turned out to be a mistake, because the rule most campgrounds state about “quiet hours” after 10 p.m. are routinely ignored, and I remember spending an uncomfortable night trying to sleep while boomboxes near and far broke the stillness with rock, rap, and mariachi music.

I recall waking from what little sleep I had gotten with a sore back and thinking how nice it would be to find a quiet hotel room somewhere and sleep for a dozen or so hours instead of embarking on what might be the most epic hike I had ever made.

But around 8 a.m., backpacks on, we parted from our friends, planning to join them at Phantom Ranch at the bottom and began our descent of the Bright Angel Trail, one of several maintained trails that descend into the canyon. It follows a prehistoric fault line that slices through the rock layers and which subsequently became a channel for flowing water — rare in these times — which eroded a pathway affording the ancient Anasazi people and modern hikers access to the bottom of the Canyon.

Layers reveal history

The layers of rock into which the Grand Canyon has been incised by the Colorado River can be thought of as a stack of books revealing segments of Earth’s history, with the most recent events in the “book” on top. From a distance, the strata (layers) may look thin, but hiking down through them makes one realize their immense breadth. Individual strata may be hundreds of feet thick, each one representing a dramatic change in the environment in which it formed.

Three of the broader layers are limestone, known in order of age from youngest to oldest as the Kaibab (Permian Period), the Redwall (Mississippian Period), and the Muav (Cambrian Period), making them between 250 and 530 million years old. These layers formed in warm, shallow seas and contain characteristic fossils such as trilobites and crinoids — also called “sea lilies,” but which in spite of their flower-like appearance are actually animals.

Yet they are interspersed with layers of sandstone called the Coconino, the Esplanade, and the Tapeats and major shale layers known as the Hermit and Bright Angel. The sandstone formed at times when the ancient seas receded and this part of the Southwest, like today, was desert characterized by vast fields of windswept dunes. Some of the outcrops exhibit the ancient tracks of lizards and other reptiles that scampered over the dunes.

But the shale layers formed when the area was under very deep waters and is often dark, indicating an environment that was oxygen-poor and mostly hostile to life, showing occasional worm tubes but few other signs of living creatures.

At the very bottom of the Canyon at the level of the Colorado River is a near-quarter-mile thick layer consisting of the Vishnu Schist, which is metamorphic, infused with fingers of the igneous Zoroaster Granite. These rocks are well over 2 billion years old and are indicative of a whole different range of formation processes: a veritable library of the region’s changing geologic history.

The strata weather and erode in different ways and at different rates, and this fact is responsible for the stunning sculptured appearance of the canyon’s landscape. Very hard rocks — such as the limestone, sandstone, and schist — tend to weather into huge vertical slabs that spall off in massive vertical slabs producing steep, precipitous slopes with enormous angular boulders at their bases.

Shale layers, on the other hand, are far less resistant to agents of weathering and erosion and result in gentler slopes, often littered with small pebbles and gravel. These processes can be observed in our own Thacher Park where the limestone rock layers of the Indian Ladder Trail have formed steep cliffs, but the long, gentler talus slopes beneath them are composed of dark shale and brittle sandstone layers, stretching down from the Helderberg plateau toward Altamont and New Salem.

At the canyon, the thickness of the strata and the varying steepness of the slopes result in the frequently scary exposure but always spectacular views offered by the various trails that descend to the Colorado River. It is not unusual to be hiking on a trail that is less than five feet wide with a sheer drop of several hundred feet off one side, and it takes us a couple of hours of hiking before we even begin to get used to the exposure, made worse by the fact that, when a mule train passes, hikers are required to stand on the outside until the last mule has gone by.

Believe me, it is a memorable experience to be perched on the edge of a cliff with a 500-foot, almost-vertical drop behind you while an odoriferous mule carrying a terrified-looking passenger lumbers by you with only inches to spare.

Indian Gardens

After about three hours, we arrived at the area known as Indian Gardens, a popular resting and watering place for hikers. Often thought of as the halfway point on the descent, it is actually about two-thirds of the way down from the South Rim in terms of elevation loss.

It is located at the interface between two important rock layers — the Muav Limestone and below it the Bright Angel Shale — part of what is known as the Tonto Group (no relation to the Lone Ranger’s companion). Here the Bright Angel Shale has weathered out into a broad plateau known as the Tonto Platform and offers respite (briefly!) from the steepness of the trail.

The Muav Limestone is somewhat permeable and can function as an aquifer, allowing the development of caves and small conduits carrying water. But the Bright Angel Shale is an aquiclude, meaning that water cannot pass through it and so the contact between the two layers features numerous springs, some with potable water.

Long ago, the ancient Anasazi people had descended the trail through the Bright Angel fault and built a series of small pueblos and kivas — underground religious structures — from the endless supply of rocks spilled down from higher up and farmed the Tonto Platform — hence the name “Indian Gardens.”

Dusty and dilapidated, the ruins of the pueblos are still visible and leave one to wonder about the mysterious people who passed their lives in this hauntingly isolated spot.

It is a gorgeous place, featuring some shade-offering cottonwood trees, and it is surrounded by towering buttes and pinnacles of varicolored rock. Their tones change from moment to moment with the movement of the sun and they cast deep, mysterious-looking shadows across the rocky wilderness.

The platform itself consists of gently rolling hills incised by steep valleys that in wet weather transport water to the Colorado River. The relative moistness of the plateau has allowed an array of desert plants to flourish there, such as cactuses and wild sage.

It was while I was following a small side trail that leads to a spring where I planned to fill my canteens that I encountered one of the canyon’s more interesting wild residents. I came upon what appeared to be a yard-long strip of pinkish leather draped over a scraggly-looking shrub and the absurd thought briefly passed through my mind that someone has lost a belt.

All at once, its nether end went vertical and an electric-sounding buzzing broke the stillness of the canyon. I froze in my tracks and realized it was a specimen of the Grand Canyon Rattler that lives nowhere else.

We regarded each other suspiciously for a few moments and then, staying well out of its private space, I made a wide arc and continue on my way, carefully watching it as I went. After a long moment, the buzzing stopped and its tail dropped. It had vanished when I returned with my full canteen so the encounter ended well for both of us, but, suitably alerted, I watched every step I took before I returned to the main trail.

As we were enjoying the leafy shade and a long cool drink of water along with some salty snacks — it’s important to maintain one’s electrolyte balance when hiking in heat — a line of mules and riders approached. The mule team leader known as the Wrangler urged all of the riders to drink plenty of water and a couple of them showing signs of overheating were hosed down with cold water from a spring.

We chatted briefly with our friends, Rich and Teresa, whose clothes were covered with dust and who admitted to looking forward to their air-conditioned cabin and a cool shower. They reported a few anxious moments on their ride as the mules apparently love to walk right on the outside edge of the trail where one misstep would send both mule and rider tumbling into the abyss. We planned to meet that evening in Phantom Ranch’s canteen for dinner.

Great Unconformity

Leaving Indian Gardens, hikers get a bit of a shock for they are soon at the top of The Devil’s Corkscrew, a dizzying series of very tight switchbacks that descend over 1,300 feet in approximately 3.5 miles. The Corkscrew offered virtually no shade and the temperature was rising steeply.

The sense of exposure is extreme and with every step hikers become aware of the fact that they are being engulfed by the lower depths of the canyon. One advances with a mixture of awe and trepidation with each dusty step.

As the trail begins its descent, a National Park sign alerts hikers to the fact that they are now passing through what geologists call the Great Unconformity. In simple terms, a geologic unconformity is the boundary between two rock or sediment layers that differ widely in age and often in composition.

A simple example can be found outside the door of anyone living on the Helderberg Plateau or in the towns that snuggle at its base. The surface sediments here are Pleistoscene — rocks and soil left behind 10,000 or so years ago when the glaciers retreated. But the sediments sit upon rock strata that come from the Devonian Period — 400 million years ago — or even earlier. That time gap between them represents an unconformity of hundreds of millions of years.

The Great Unconformity is in no way attention-grabbing, and without the sign no one lacking an extensive knowledge of geology would be likely to take a second look at it. Layered 550-million-year-old Tapeats Sandstone rests tightly on the quarter-mile-thick Vishnu Schist — a metamorphic rock — containing intrusions of the igneous rock granite.

The schist represents very ancient shale layers pressed and folded and cooked in a mountain-forming episode called an orogeny. It is all that remains of what was once a range of near-Himalayan heights that rose around 2 billion years ago — close to half of the age of the Earth — and was then ground down steadily over hundreds of millions of years by the agents of erosion.

In other words — in a space too thin to place one’s fingers in, something close to 1.8 billion years of Earth’s history has been wiped away. We know this because, in many other places in the United States and in the world, rocks of the intervening eons have been discovered.

The Great Unconformity can be seen in other parts of the Southwest, but nowhere is it visible in a setting more dramatic than this. And given the hardness of this inner canyon rock, the Devil’s Corkscrew features drop-offs between its tight switchbacks that are vertigo-inducing and we found ourselves grateful that we were not on mule-back.

Reaching the river

It was now near noon, and as the sun had ascended into the cloudless Arizona sky, its light being concentrated in the confines of this canyon-within-the-canyon, the temperature soared. Descending the meanders of the Corkscrew is numbing: left turn, right turn, left turn, right turn again down a rock-strewn trail, kicking up dust with every step and trying hard to avoid deposits of mule-poop.

The gradient was so steep we had to force ourselves to hold back from a trot — unthinkable in this heat and with such unstable footing. In the stark sunlight, the varying colors of the rock layers seemed to be bleaching to dull shades of tan and everywhere there were dusty cactuses of several kinds, constant reminders that we are in the desert — as if we needed such reminders.

In less than an hour, we reached the banks of the Colorado River, and what appeared from the South Rim to be a narrow, lazily-moving muddy stream was revealed as a roaring flood, its waters faded brick-red from the rust-colored sediments it carries.

Perched on the bank was a small shady shelter where hikers could fill their canteens with fresh water and there is usually a park ranger to offer aid and answer questions. Everyone entering the cool interior remarked on the oppressive dry heat and to our astonishment the ranger told the assembled group, “You folks are lucky — it’s only 107 today. Yesterday at this time it was 123!”

Whatever good news that represented, the fact is that we were still 2.3 miles from the Bright Angel campground near Phantom Ranch. Before we started our trek, we had cut down what we were going to carry to the absolute minimum equipment we would need for a single-night stay — about 15 pounds each. Descending the trail in the cooler morning, the packs had not seemed so much of a burden.

But as we commenced our hike along the river toward the campground they seemed to gain weight with each step and there was absolutely no shade. Moreover, the rock-littered, dusty trail along the river is not flat — it goes up over and down a series of hills and gulches formed from massive piles of talus that have spalled off from the higher elevations.

In the wilting heat and with the droning of the river’s rapids, the hike is punishing. The spectacular scenery rising above us offered little consolation for the ordeal and we realized that no matter how much water we guzzled from our canteens on the way down, it was not enough: We were feeling the effects of dehydration.

On to camp

After what seemed like hours — but was really only about one — we spotted the sturdy metal bridge across the Colorado that leads to Bright Angel Campground and we gratefully crossed it, only a few yards above the roiling waters of the Colorado River.

On the far side near some cottonwood trees are the remains of still another Anasazi pueblo and a kiva close to where the Bright Angel Creek spills down from the North Rim of the Canyon to join the Colorado — another green place in the desiccated wilderness of the canyon.

Beyond them is the campground, and after checking in we hit the snack bar and guzzled what must have been two quarts of cold lemonade each. We then proceeded to put on our bathing suits and go to join other exhausted hikers sitting in the creek and letting the cold stream spilling down from the North Rim of the canyon refresh us.

Later in the afternoon, Rich and Teresa arrived and showed us their cabin. It is Spartan — but its air-conditioner works; it has water for hot showers; and. though the beds look like they came from a college dormitory, we are assured that they are clean and comfortable.

We assemble at dinner time in the Phantom Ranch canteen. Meals are served family-style at long tables — like at a church supper. Steve and I have pre-ordered beef stew with chocolate cake for dessert, and perhaps it is the effect of our day’s ordeal or perhaps it is the spectacular setting but the humble stew tastes like the specialty of a five-star restaurant and the cake seems the equivalent of some gourmet French pastry.

In any case, we wash it all down with glass after glass of cold lemonade and, after dinner, Rich and Teresa head off to their air-conditioned cabin for a good night’s rest in a real bed. At dawn the next day, they will again mount up on their mules and head back up to the South Rim.

They will be following the South Kaibab Trail, which most guidebooks tell hikers ascending the canyon to avoid as it has almost no shade and is even steeper than the Bright Anger Trail. Steve and I head over to a small amphitheater located near the river for the evening ranger presentation.

The temperature is still in the nineties, but what is a ranger presentation without a bonfire? So the woman ranger who is conducting the presentation has built a small fire that crackles and spits agreeably, but in this dry heat not one of the two dozen or so hikers gathered for her talk wants to be near it.

Before she starts, we have time to contemplate the setting: We are seated on primitive benches situated on some of the oldest rock on Earth’s surface, surrounded by towering mesas, buttes, and pinnacles slowly sinking into purple shadows in the approaching twilight. Far above us and several miles away, tiny lights from the hotels scattered along the South Rim glitter dimly like mirages and above them in the clear violet sky the planet Venus gleams.

The ranger takes the podium and says to the gathered crowd: “Congratulations everybody! You have hiked to the bottom of the Grand Canyon, something very few people ever have the opportunity or the stamina to do!”