To hike the Grand Canyon is to walk backwards through time… Part One: The descent

Everyone remembers the first time they see the Grand Canyon.

Mine came over half a century ago when I was 14 and it is still burned into my memory along with my first sight of the Giza pyramids; my first close-up look at an erupting volcano; and my first view — from a hillside fragrant with pine resin called The Pnyx — of the Parthenon at night glowing in subdued flood lamps above the noisy, twinkling streets of Athens like a vision from myth.

My family was on a cross-country trip and we had driven up from Phoenix, Arizona that day. The first half of the drive had been blisteringly hot.

Cars did not have air-conditioning in those days and my mother and father had shared the driving, but even today it is a tiring trip, passing first through forests of giant saguaro cactuses, then ascending through cool mountain meadows where elk wander and, skirting Flagstaff, heading into high desert where the apparently endless flat terrain gives no hint of the awe-inducing landscape that lies just to the north.

We arrived around 10 at night at the venerable Bright Angel Lodge where my parents had reserved a cabin that was close to the South Rim of the canyon. They were both looking forward to getting a shower and a good night’s sleep but I remember being appalled that they did not first want to see the canyon. Assured by the hotel clerk that there was a safe viewing deck right behind the main lodge, I took off on my own, promising to join the family at our cabin in 15 minutes.

The clerk directed me to a doorway that led out onto the deck and it took a few moments for my eyes to get accustomed to the darkness. The bright first-quarter moon had risen in the eastern sky and slowly there emerged from the dark vastness the silhouettes of great craggy pinnacles and towers and though in the dark it was impossible to gauge size or distance, I could tell what lay before me were massive structures stretching to the horizon.

Far, far below was what appeared to be a thin, meandering line drawn in softly luminous ink — my first glimpse of the far-away Colorado River. A mild breeze was rising from the depths, carrying with it the fragrance of sage and other desert plants, an odor I have heard described as “desert incense.”

An eerie howl was the only sound that broke the overwhelming stillness — perhaps somebody’s dog, though at 14 I was sure I was hearing a coyote. However — I have since spent enough time in the Southwest to realize that it probably was a coyote as these critters are ubiquitous in the deserts.

At any rate, with that unearthly sound, I suddenly became aware that a dark, precipitous abyss lay before me and for a moment I steadied myself against the retaining wall that surrounded the deck as I was overcome with the vertiginous sensation that I was about to be pulled over the side. I remember withdrawing into the light of the lobby of the lodge where everything was on a more human scale and running to our cabin.

The next morning, my father took my sister and me on a short hike down the iconic Bright Angel Trail that leads down to the Colorado River. We were on a tight schedule and had to meet relatives in Los Angeles in two days but Dad wanted us to have the experience of being down in the canyon instead of just seeing it from the top.

My mother declined and opted for a walk on one of the paths that run along the canyon rim, meandering through desert plants and offering dizzying views of the spectacularly colorful rock formations below.

My recollection is that we walked not more than a half-mile down the steep, dusty trail and foolishly had not brought any water. The South Rim is at 7,000 feet and tends to be fairly cool even in summer, but one of the great misconceptions novice hikers entertain — and we were definitely novices! — is that temperatures down in the Canyon are cooler than at the rim. (Fact: Temperatures tend to decrease with increasing elevation, and increase with decreasing elevation, a lesson I certainly knew many years later but did not appreciate until I hiked with a friend all the way to the bottom.)

I had been a rock collector since I was around 5 years of age but at 14 I knew very little about geology though I had read in a guidebook that the canyon had been cut by the Colorado River over millions of years. I was fascinated by the fact that the rocks were in layers of many different colors even if I had no idea why — Dad probably tried to explain that to me, but who remembers lessons from when you are 14?

We probably descended 500 feet or so below the canyon rim — following, as it turns out, a route first used by the ancestral pueblo people long known to history as the Anasazi. Beautiful as the scenery was, I remember being surrounded by the massive stone forms and experiencing again the feeling of vertigo as we gazed off into the immense gulfs of the canyon.

It was with some relief that my father told us that we had to head back up to meet Mom and take a drive along the rim to see more of the awesome scenery before we left on the next leg of our drive west. In all, we spent less than 24 hours at the canyon — fairly typical for the average tourist even today.

But that brief descent of the Bright Angel Trail remained lodged in my memory as one of the highlights — albeit a bit scary — of our California trip. And the sight of the far-away bottom of the canyon and that narrow-seeming Colorado River surely fired my determination to come back someday and hike all the way down.

Return to the canyon

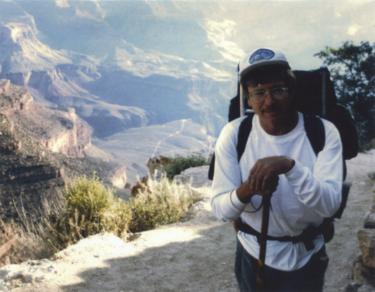

It was many years later that I returned to the Grand Canyon (rather more than fully grown!) but this time with several friends: a fellow hiker named Steve with whom I planned to hike to the bottom and tent overnight in the Bright Angel Campground near legendary Phantom Ranch, and an old high school buddy named Rich and his wife who were going to do the mule ride down to the bottom and stay in one of the rustic (but air-conditioned) cabins at the Ranch.

We arrived on a deceptively cool August evening after a long drive from New Mexico and spent the night before our trek in the park campground. This turned out to be a mistake, because the rule most campgrounds state about “quiet hours” after 10 p.m. are routinely ignored, and I remember spending an uncomfortable night trying to sleep while boomboxes near and far broke the stillness with rock, rap, and mariachi music.

I recall waking from what little sleep I had gotten with a sore back and thinking how nice it would be to find a quiet hotel room somewhere and sleep for a dozen or so hours instead of embarking on what might be the most epic hike I had ever made.

But around 8 a.m., backpacks on, we parted from our friends, planning to join them at Phantom Ranch at the bottom and began our descent of the Bright Angel Trail, one of several maintained trails that descend into the canyon. It follows a prehistoric fault line that slices through the rock layers and which subsequently became a channel for flowing water — rare in these times — which eroded a pathway affording the ancient Anasazi people and modern hikers access to the bottom of the Canyon.

Layers reveal history

The layers of rock into which the Grand Canyon has been incised by the Colorado River can be thought of as a stack of books revealing segments of Earth’s history, with the most recent events in the “book” on top. From a distance, the strata (layers) may look thin, but hiking down through them makes one realize their immense breadth. Individual strata may be hundreds of feet thick, each one representing a dramatic change in the environment in which it formed.

Three of the broader layers are limestone, known in order of age from youngest to oldest as the Kaibab (Permian Period), the Redwall (Mississippian Period), and the Muav (Cambrian Period), making them between 250 and 530 million years old. These layers formed in warm, shallow seas and contain characteristic fossils such as trilobites and crinoids — also called “sea lilies,” but which in spite of their flower-like appearance are actually animals.

Yet they are interspersed with layers of sandstone called the Coconino, the Esplanade, and the Tapeats and major shale layers known as the Hermit and Bright Angel. The sandstone formed at times when the ancient seas receded and this part of the Southwest, like today, was desert characterized by vast fields of windswept dunes. Some of the outcrops exhibit the ancient tracks of lizards and other reptiles that scampered over the dunes.

But the shale layers formed when the area was under very deep waters and is often dark, indicating an environment that was oxygen-poor and mostly hostile to life, showing occasional worm tubes but few other signs of living creatures.

At the very bottom of the Canyon at the level of the Colorado River is a near-quarter-mile thick layer consisting of the Vishnu Schist, which is metamorphic, infused with fingers of the igneous Zoroaster Granite. These rocks are well over 2 billion years old and are indicative of a whole different range of formation processes: a veritable library of the region’s changing geologic history.

The strata weather and erode in different ways and at different rates, and this fact is responsible for the stunning sculptured appearance of the canyon’s landscape. Very hard rocks — such as the limestone, sandstone, and schist — tend to weather into huge vertical slabs that spall off in massive vertical slabs producing steep, precipitous slopes with enormous angular boulders at their bases.

Shale layers, on the other hand, are far less resistant to agents of weathering and erosion and result in gentler slopes, often littered with small pebbles and gravel. These processes can be observed in our own Thacher Park where the limestone rock layers of the Indian Ladder Trail have formed steep cliffs, but the long, gentler talus slopes beneath them are composed of dark shale and brittle sandstone layers, stretching down from the Helderberg plateau toward Altamont and New Salem.

At the canyon, the thickness of the strata and the varying steepness of the slopes result in the frequently scary exposure but always spectacular views offered by the various trails that descend to the Colorado River. It is not unusual to be hiking on a trail that is less than five feet wide with a sheer drop of several hundred feet off one side, and it takes us a couple of hours of hiking before we even begin to get used to the exposure, made worse by the fact that, when a mule train passes, hikers are required to stand on the outside until the last mule has gone by.

Believe me, it is a memorable experience to be perched on the edge of a cliff with a 500-foot, almost-vertical drop behind you while an odoriferous mule carrying a terrified-looking passenger lumbers by you with only inches to spare.

Indian Gardens

After about three hours, we arrived at the area known as Indian Gardens, a popular resting and watering place for hikers. Often thought of as the halfway point on the descent, it is actually about two-thirds of the way down from the South Rim in terms of elevation loss.

It is located at the interface between two important rock layers — the Muav Limestone and below it the Bright Angel Shale — part of what is known as the Tonto Group (no relation to the Lone Ranger’s companion). Here the Bright Angel Shale has weathered out into a broad plateau known as the Tonto Platform and offers respite (briefly!) from the steepness of the trail.

The Muav Limestone is somewhat permeable and can function as an aquifer, allowing the development of caves and small conduits carrying water. But the Bright Angel Shale is an aquiclude, meaning that water cannot pass through it and so the contact between the two layers features numerous springs, some with potable water.

Long ago, the ancient Anasazi people had descended the trail through the Bright Angel fault and built a series of small pueblos and kivas — underground religious structures — from the endless supply of rocks spilled down from higher up and farmed the Tonto Platform — hence the name “Indian Gardens.”

Dusty and dilapidated, the ruins of the pueblos are still visible and leave one to wonder about the mysterious people who passed their lives in this hauntingly isolated spot.

It is a gorgeous place, featuring some shade-offering cottonwood trees, and it is surrounded by towering buttes and pinnacles of varicolored rock. Their tones change from moment to moment with the movement of the sun and they cast deep, mysterious-looking shadows across the rocky wilderness.

The platform itself consists of gently rolling hills incised by steep valleys that in wet weather transport water to the Colorado River. The relative moistness of the plateau has allowed an array of desert plants to flourish there, such as cactuses and wild sage.

It was while I was following a small side trail that leads to a spring where I planned to fill my canteens that I encountered one of the canyon’s more interesting wild residents. I came upon what appeared to be a yard-long strip of pinkish leather draped over a scraggly-looking shrub and the absurd thought briefly passed through my mind that someone has lost a belt.

All at once, its nether end went vertical and an electric-sounding buzzing broke the stillness of the canyon. I froze in my tracks and realized it was a specimen of the Grand Canyon Rattler that lives nowhere else.

We regarded each other suspiciously for a few moments and then, staying well out of its private space, I made a wide arc and continue on my way, carefully watching it as I went. After a long moment, the buzzing stopped and its tail dropped. It had vanished when I returned with my full canteen so the encounter ended well for both of us, but, suitably alerted, I watched every step I took before I returned to the main trail.

As we were enjoying the leafy shade and a long cool drink of water along with some salty snacks — it’s important to maintain one’s electrolyte balance when hiking in heat — a line of mules and riders approached. The mule team leader known as the Wrangler urged all of the riders to drink plenty of water and a couple of them showing signs of overheating were hosed down with cold water from a spring.

We chatted briefly with our friends, Rich and Teresa, whose clothes were covered with dust and who admitted to looking forward to their air-conditioned cabin and a cool shower. They reported a few anxious moments on their ride as the mules apparently love to walk right on the outside edge of the trail where one misstep would send both mule and rider tumbling into the abyss. We planned to meet that evening in Phantom Ranch’s canteen for dinner.

Great Unconformity

Leaving Indian Gardens, hikers get a bit of a shock for they are soon at the top of The Devil’s Corkscrew, a dizzying series of very tight switchbacks that descend over 1,300 feet in approximately 3.5 miles. The Corkscrew offered virtually no shade and the temperature was rising steeply.

The sense of exposure is extreme and with every step hikers become aware of the fact that they are being engulfed by the lower depths of the canyon. One advances with a mixture of awe and trepidation with each dusty step.

As the trail begins its descent, a National Park sign alerts hikers to the fact that they are now passing through what geologists call the Great Unconformity. In simple terms, a geologic unconformity is the boundary between two rock or sediment layers that differ widely in age and often in composition.

A simple example can be found outside the door of anyone living on the Helderberg Plateau or in the towns that snuggle at its base. The surface sediments here are Pleistoscene — rocks and soil left behind 10,000 or so years ago when the glaciers retreated. But the sediments sit upon rock strata that come from the Devonian Period — 400 million years ago — or even earlier. That time gap between them represents an unconformity of hundreds of millions of years.

The Great Unconformity is in no way attention-grabbing, and without the sign no one lacking an extensive knowledge of geology would be likely to take a second look at it. Layered 550-million-year-old Tapeats Sandstone rests tightly on the quarter-mile-thick Vishnu Schist — a metamorphic rock — containing intrusions of the igneous rock granite.

The schist represents very ancient shale layers pressed and folded and cooked in a mountain-forming episode called an orogeny. It is all that remains of what was once a range of near-Himalayan heights that rose around 2 billion years ago — close to half of the age of the Earth — and was then ground down steadily over hundreds of millions of years by the agents of erosion.

In other words — in a space too thin to place one’s fingers in, something close to 1.8 billion years of Earth’s history has been wiped away. We know this because, in many other places in the United States and in the world, rocks of the intervening eons have been discovered.

The Great Unconformity can be seen in other parts of the Southwest, but nowhere is it visible in a setting more dramatic than this. And given the hardness of this inner canyon rock, the Devil’s Corkscrew features drop-offs between its tight switchbacks that are vertigo-inducing and we found ourselves grateful that we were not on mule-back.

Reaching the river

It was now near noon, and as the sun had ascended into the cloudless Arizona sky, its light being concentrated in the confines of this canyon-within-the-canyon, the temperature soared. Descending the meanders of the Corkscrew is numbing: left turn, right turn, left turn, right turn again down a rock-strewn trail, kicking up dust with every step and trying hard to avoid deposits of mule-poop.

The gradient was so steep we had to force ourselves to hold back from a trot — unthinkable in this heat and with such unstable footing. In the stark sunlight, the varying colors of the rock layers seemed to be bleaching to dull shades of tan and everywhere there were dusty cactuses of several kinds, constant reminders that we are in the desert — as if we needed such reminders.

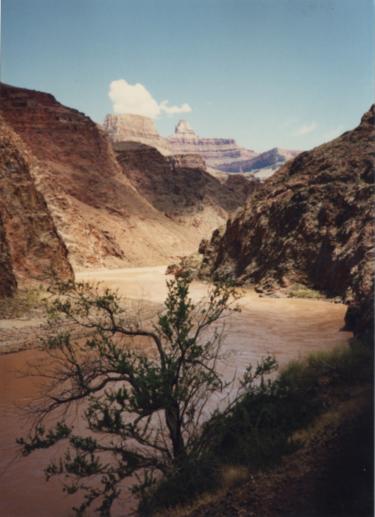

In less than an hour, we reached the banks of the Colorado River, and what appeared from the South Rim to be a narrow, lazily-moving muddy stream was revealed as a roaring flood, its waters faded brick-red from the rust-colored sediments it carries.

Perched on the bank was a small shady shelter where hikers could fill their canteens with fresh water and there is usually a park ranger to offer aid and answer questions. Everyone entering the cool interior remarked on the oppressive dry heat and to our astonishment the ranger told the assembled group, “You folks are lucky — it’s only 107 today. Yesterday at this time it was 123!”

Whatever good news that represented, the fact is that we were still 2.3 miles from the Bright Angel campground near Phantom Ranch. Before we started our trek, we had cut down what we were going to carry to the absolute minimum equipment we would need for a single-night stay — about 15 pounds each. Descending the trail in the cooler morning, the packs had not seemed so much of a burden.

But as we commenced our hike along the river toward the campground they seemed to gain weight with each step and there was absolutely no shade. Moreover, the rock-littered, dusty trail along the river is not flat — it goes up over and down a series of hills and gulches formed from massive piles of talus that have spalled off from the higher elevations.

In the wilting heat and with the droning of the river’s rapids, the hike is punishing. The spectacular scenery rising above us offered little consolation for the ordeal and we realized that no matter how much water we guzzled from our canteens on the way down, it was not enough: We were feeling the effects of dehydration.

On to camp

After what seemed like hours — but was really only about one — we spotted the sturdy metal bridge across the Colorado that leads to Bright Angel Campground and we gratefully crossed it, only a few yards above the roiling waters of the Colorado River.

On the far side near some cottonwood trees are the remains of still another Anasazi pueblo and a kiva close to where the Bright Angel Creek spills down from the North Rim of the Canyon to join the Colorado — another green place in the desiccated wilderness of the canyon.

Beyond them is the campground, and after checking in we hit the snack bar and guzzled what must have been two quarts of cold lemonade each. We then proceeded to put on our bathing suits and go to join other exhausted hikers sitting in the creek and letting the cold stream spilling down from the North Rim of the canyon refresh us.

Later in the afternoon, Rich and Teresa arrived and showed us their cabin. It is Spartan — but its air-conditioner works; it has water for hot showers; and. though the beds look like they came from a college dormitory, we are assured that they are clean and comfortable.

We assemble at dinner time in the Phantom Ranch canteen. Meals are served family-style at long tables — like at a church supper. Steve and I have pre-ordered beef stew with chocolate cake for dessert, and perhaps it is the effect of our day’s ordeal or perhaps it is the spectacular setting but the humble stew tastes like the specialty of a five-star restaurant and the cake seems the equivalent of some gourmet French pastry.

In any case, we wash it all down with glass after glass of cold lemonade and, after dinner, Rich and Teresa head off to their air-conditioned cabin for a good night’s rest in a real bed. At dawn the next day, they will again mount up on their mules and head back up to the South Rim.

They will be following the South Kaibab Trail, which most guidebooks tell hikers ascending the canyon to avoid as it has almost no shade and is even steeper than the Bright Anger Trail. Steve and I head over to a small amphitheater located near the river for the evening ranger presentation.

The temperature is still in the nineties, but what is a ranger presentation without a bonfire? So the woman ranger who is conducting the presentation has built a small fire that crackles and spits agreeably, but in this dry heat not one of the two dozen or so hikers gathered for her talk wants to be near it.

Before she starts, we have time to contemplate the setting: We are seated on primitive benches situated on some of the oldest rock on Earth’s surface, surrounded by towering mesas, buttes, and pinnacles slowly sinking into purple shadows in the approaching twilight. Far above us and several miles away, tiny lights from the hotels scattered along the South Rim glitter dimly like mirages and above them in the clear violet sky the planet Venus gleams.

The ranger takes the podium and says to the gathered crowd: “Congratulations everybody! You have hiked to the bottom of the Grand Canyon, something very few people ever have the opportunity or the stamina to do!”

She points out the towering structures of stone and explains the origin of some of their names: Zoroaster Temple, Cheops Pyramid, Shiva Temple, Vulcan’s Throne, Isis Temple — names to conjure by if we were not all too tired to conjure. She talks about the geology of the rock strata and their mind-numbing age and explains how the flowing waters of the Colorado River and the thousands of small side canyons have carved this great abyss over millions of years. The crowd is silent — partly out of exhaustion but mostly in awe of her presentation

Then all at once she says, “Now I’m going to give you the bad news. You, ladies and gentlemen, have hiked to the bottom of the Grand Canyon, one of the deepest water-cut gorges on Earth. And tomorrow morning, you are going to have to haul your butts up and out of it!”

The poetry of the moment disappears, and all at once it hits us: Today we hiked down into this spectacular place in the oppressive heat. Tomorrow we have to do it in reverse — and the Devil’s Corkscrew looms in our imaginations like the challenge of a lifetime.