Grand Canyon Part Two: The ascent

It is impossible to sleep.

Before we had crawled into our tent, we had noticed that the rocky outcrops around us were still warm, radiating the heat absorbed from the sun during the day. On top of that, there is hardly any breeze stirring, though we had read that cool, dense air from the North Rim of the Grand Canyon often sinks down to the river in the evenings, providing respite from the day’s high temperatures.

Not tonight.

The air is still and uncomfortably hot and dry. Some campers have their tent flaps open; others are simply sprawled out on the ground in their sleeping bags or on picnic tables, but my encounter with the rattlesnake on our hike down and warnings about scorpions have made me determined not to sleep without the protection of a screened tent around me.

In addition, I am being kept awake by the dryness of the air that is sapping our bodies’ moisture and making me thirsty. The Bright Angel Campground is fairly crowded and there is the nearly constant muffled sound of voices from people as restless as we are.

Undoubtedly adding to everyone’s discomfort are the words of the Park Ranger at the evening campfire: “Now I’m going to give you the bad news. You, ladies and gentlemen, have hiked to the bottom of the Grand Canyon, one of the deepest water-cut gorges on Earth. And tomorrow morning, you are going to have to haul your butts up and out of it!”

I had slept poorly the night before we had started our hike and the strain on our leg muscles of hiking steeply downhill coupled with dehydration requires a good night’s rest but it is obvious we are not going to get it, and sometime around 4 a.m., Steve says, “This is crazy. There is no way I am going to get any sleep. While it’s still dark let’s get moving.”

By the light of our headlamps, we load up our tent and poles in our backpacks and deliver them to the mule stable — we had discovered just before we attempted to retire for the night that for 50 bucks, the mules will haul our backpacks up to the South Rim, so we need only the light day packs we have brought and our canteens. To our surprise, the Phantom Ranch snack bar is open at that hour and we purchase a couple of trail lunches for the ascent.

As we leave the campground, the first faint light begins to glow in the east but we keep our headlamps on as we make our way over toward the river to avoid confronting snakes or scorpions. The sky brightens surprisingly fast and, by the time we reach the bridge over the Colorado River, there is sufficient light to walk without headlamps. The air now seems for the moment pleasantly cool and we are cheered by the thought that we may be able to get up and out of the Devil’s Corkscrew before the worst heat comes.

A moment to remember

Just as we start to cross the bridge, dawn’s red sunlight hits the tops of the mesas and jagged buttes and pinnacles, making them look like glowing embers and we stop to take in the spectacular scene. Just a few yards beneath us, the turbulent currents of the muddy Colorado rumble over boulders in its bed — the only sound that breaks the stillness — and the bridge vibrates with the river’s power.

There is not another living soul in sight — it is as though we are the only two people in the canyon, a moment to remember all of our lives.

The trek back along the bank of the river somehow seems less of an ordeal than it had the previous day, perhaps because we know with every step the South Rim is closer. Along with our friends Rich and Teresa, we have made reservations for that night at the venerable El Tovar Lodge, which has a swimming pool, a highly-regarded dining room, and air-conditioning.

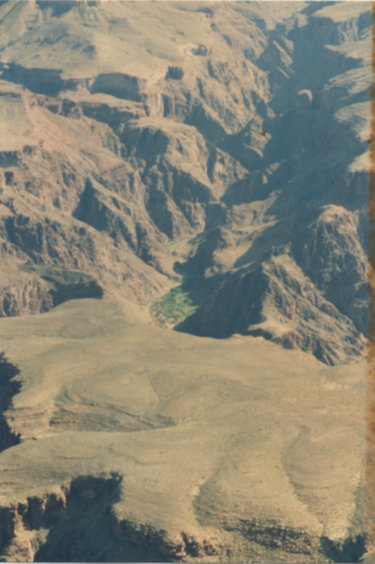

But between Bright Angel campground and the South Rim lie 4,500 feet of elevation gain over 10.3 miles of trail and those facts provide a reality check to the elation we have felt in our view from the bridge.

We arrive at the base of the Devil’s Corkscrew and we each guzzle close to a quart of water before we begin to climb. From below, the torturous twists and turns of the trail are not very obvious and we discover to our pleasure that the steep, stony trail is in some ways easier to ascend than it was to descend for the simple reason that gravity is not forcing us forward and down at awkward angles with each step. Also, at this early hour of the day — it is around 6 a.m. — much of the Corkscrew is in shadow, tucked as it is in its own side canyon.

We pass a few lone hikers headed down who have also taken advantage of the cool morning — they must have started their descent around 2 a.m. Oddly, except for exchanging hasty greetings, no one stops to chat — everyone hiking wants to get the Corkscrew behind them.

As we climb, we make occasional brief stops to let the muscles in our legs relax but the lure of getting back to Indian Gardens before the sun begins again to turn the Corkscrew into a furnace is irresistible. We are also pleased to discover that, with increasing altitude, the temperature is staying steady or perhaps even dropping.

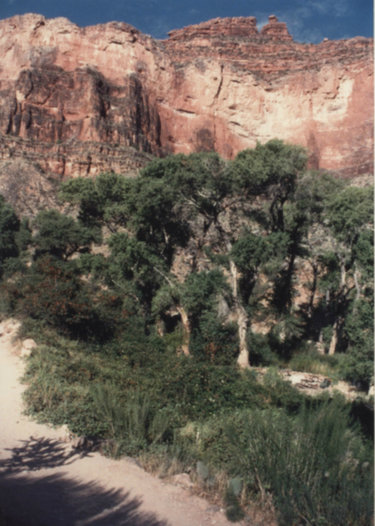

This seems to energize us and within an hour we have reached the sign describing the Great Unconformity — the Corkscrew is now history. The green cottonwoods of Indian Gardens and the cool shade they offer seem a prize for our morning’s efforts and we take a break for water and snacks.

Intricate features revealed

Descending Bright Angel Trail, we were rewarded with the vast, panoramic views of the canyon with its stunningly sculptured towers of rock. But on the ascent our backs are to the long views much of the time and the intricate features of the various layers of sandstone and limestone are revealed.

The National Park Service has set up labelled displays of the fossils: There are trilobites and their fossilized trails, brachiopods — oyster-like shellfish — snails and fragments of crinoids, commonly known as sea-lilies. Incredible to think that hundreds of millions of years ago this bone-dry environment was from time to time under a warm, shallow sea dotted with reefs and islands like today’s Bahamas.

Yet in between the limestone strata are the various strata of sandstone, and these show thin laminated layers meeting each other at odd angles: features known as cross-bedding, representing petrified deposits of sand left there by ancient shifting winds. This tells of Earth’s surface cyclically heaving upward, causing prehistoric seas to retreat and turning the landscape into desert as it is once more today.

In many places, in the precipitous, far-off limestone cliffs there are dark cave openings that in times of unusually wet weather may even today gush water. Most are unexplored as it is appallingly dangerous to get to them: Explorers must either rappel down from hundreds of feet above the entrances or do challenging rock climbs from below.

The caves are very ancient features and the few that have been entered have yielded stalactites and stalagmites which have been radiometrically dated to over 7 million years ago. But were these caves here before the Grand Canyon formed or are they more recent? The answers are controversial and contradicting and are part of the centuries-long debate as to just how and just when the Grand Canyon came to be.

As we climb above Indian Gardens, we encounter increasing numbers of hikers, a few bound for Phantom Ranch and the campground, many for Plateau Point.

One young couple says, “We’re almost down to the river, aren’t we?” and we gently explain that they still have a long way to go. They have no idea what the Devil’s Corkscrew is and we realize then that they are not following a map.

In addition, the young man is wearing open-toed sandals and at the end of the hike is likely to have blisters on his feet the size of golf balls. But rather than trying to scare them with dire warnings, we tactfully suggest that, given their inexperience and the rising temperatures as they descend, they might want to turn around at Plateau Point — which, to be sure, is far deeper into the canyon than most visitors go.

They seem grateful for the advice and head off downward energetically. As the saying goes, “Experience is the best teacher.”

End in sight

It is now late morning and we are approaching the last switchbacks of the trail before we reach the South Rim. We are dusty and sweaty and obviously look tired but are exhilarated to see the end of the challenge so close now.

The temperature has continued to remain steady as we climb and now stands in the low 70s — fine for hiking. This section of the trail is crowded with visitors, many with little kids, doing just as my family did those many years ago — descending a few hundred feet on the Bright Angel Trail to get a feeling for being in the canyon instead of just looking at it, as it were, from the outside.

A ranger we talk to later informs us that a survey has revealed that the average time visitors actually spend looking at the Grand Canyon is a minuscule 12 minutes before they head off to the souvenir shops, the game rooms, and swimming pools of the hotels, or one of the numerous food services. To me, this is comparable to someone’s standing on a bluff on the New Jersey side of the Hudson River, taking a couple of quick selfies with the skyscrapers of Manhattan in the background, and texting friends that they have been to New York City.

Following directions in our trail guide, just before we reach the rim we take a look into an inconspicuous hollow above the trail and there we see pictographs left by the Anasazi or one of the other ancient peoples who have made their ways into the canyon. A handprint and figures of deer and other animals appear in red paint, surprisingly well-preserved in this dry environment even though vandals have managed to find and mar some of them.

Their presence emphasizes the long history of the trail and evokes admiration for people with primitive equipment who must have been motivated by the same sense of awe and wonder that lures hikers today.

As we arrive at the rim, several people come over to ask if we have come up from the bottom and seem impressed when we answer in the affirmative. One elderly man says, “It must be a great experience,” and sounds wistful.

“Yes, yes it is,” is our response. “It really is.”

Not particularly eloquent, of course — but sometimes simple words convey the most truth.

In any case, no question we hear matches what a park ranger tells us he was asked upon emerging from one of his many trips into and out of the canyon. A middle-aged couple approached him — dusty and sweating and sunburned like ourselves — and asked if he had been to the bottom, and when he replied that he had, the woman asked, “Is there anything down there?”

As the saying goes: If you have to ask a question like that, you would never understand the answer.

We head for our hotel, a hot shower, a good dinner with a celebratory glass of wine, and a well-deserved night in a real bed. And, as was true of so many before us who have descended into the depths of the Grand Canyon, we dream.