Zetzsche faces up to 20 years, guilty of manslaughter

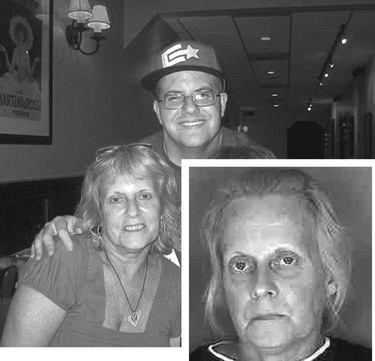

ALBANY COUNTY — Mental health experts on both sides agreed that Tracey Zetzsche had no recollection of the death of her 22-year-old son in their Westerlo apartment last summer, the basis of her guilty plea to first-degree manslaughter, with up to 20 years in prison. Judge Stephen Herrick accepted an Alford plea from Zetzsche in Albany County Court on Thursday, Sept 12.

Zetzsche, 53, pleaded guilty, concluding that prosecutors could present evidence that would likely result in her conviction, said her attorney, Albany County Public Defender James Milstein. The Alford plea is not a direct admission of wrongdoing like a guilty plea.

“In this case, she is not asserting her innocence, she is asserting she has no memory of the crime as it happened,” said Cecilia Walsh, spokeswoman for the Albany County District Attorney’s office.

While amnesia was the justification for the plea deal, Milstein said, the issue for her defense was whether or not she suffered from any mental disease that impaired her memory during the time of her son’s death.

“I think, in general, society has become more attuned to people with mental illness,” said Milstein. “Even with people with mental illness there is a higher threshold in the criminal justice system for it to rise to the level of it being a defense, and that is something I wish to comment more on after the case is completed.”

Neither Milstein nor Walsh would comment on the findings of the forensic psychiatrists for the case. Herrick sealed documents introduced by both sides.

Zetzsche could have faced 25 years to life in prison if convicted on the second-degree murder charge made last summer. She faces 18 to 20 years for manslaughter at her sentencing, scheduled for Nov. 1.

Her son, 22-year-old Gabriel Philby-Zetzsche, died from stab wounds to his chest and blunt force head trauma, according to the county coroner. With cerebral palsy, Philby-Zetzsche’s left arm, his vision, and his ability to walk were all impaired as a result of being deprived of oxygen at birth, said Holly Tobin, who is a co-owner of the VanWinkle Inn in South Westerlo, where Zetzsche had worked; Tobin is a nurse. Philby-Zetzsche had a twin sister who died just days after they were born, Tobin said.

The mother and son had rented an apartment in Westerlo over the P & L Deli on Route 143 for almost a year; they were originally from Commack, Long Island. Zetzsche worked as a chambermaid at two different Hilltown hotels and struggled to pay rent, people who knew her told The Enterprise at the time of the murder.

Zetzsche’s sister-in-law found her sitting on the steps, wrapped in a blanket outside the deli, on July 30, 2012, which led discovery of the bludgeoned body.

“She’d come here with Gabe. They went up to the motel behind the restaurant, and she did rooms,” Jim Molloy, co-owner of the Hollowbrook Inn, where Zetzsche last worked, told The Enterprise in August after she was arrested. “He’d follow her around sometimes, or he’d sit under the apple trees, or on the porch upstairs. From what we could tell, she was a good mother. She never yelled at him. We never saw her yell or get mad.”

When Philby-Zetzsche’s body was found, he had been dead for days, fans were pointed out the windows, and knives and a claw hammer were found wrapped in bloody sheets in the garbage, police said; Zetzsche had lacerations and bruises on her hands and body.

Sheriff Craig Apple said at the time of her arrest that Zetzsche said she had no memory of the crime and she also said there was no one else in the apartment.

“I’m not buying into it 100 percent, because some of the statements did contradict themselves, but I’m glad that the case was adjudicated,” said Apple this week, adding that the potential sentence fits the crime. Apple said he had never seen such a case of memory loss in his career.

Memory and crime

It is difficult to verify genuine amnesia, experts say, because memory isn’t studied as a uniform concept and it doesn’t have a central mechanism, but different types of information and their timing are the responsibility of multiple parts of the brain.

“It is not a recording like a tape recorder or a CD,” said Dr. Robert P. Granacher, a University of Kentucky professor of clinical psychiatry who conducts neuropsychiatric evaluations in private practice and serves as a medical witness in trials. “It’s a process. It’s a complicated process that uses multiple sites in the brain and has to be integrated for it to have any useful function at all.”

As a rule in forensic medicine, Granacher said, the multiple tools — knives and a hammer — indicate separate choices.

“So she has to be able to prove that she can’t remember any of those choices, which then makes it less credible that she has true amnesia,” said Granacher.

Researchers categorize memory for types of information into declarative — facts, events, and autobiographical information — and procedural, which involves skills, or how to do things.

Granacher said that Zetzsche’s memory loss for a period of days suggests traumatic, psychological stress was not the cause. It’s more likely organic, he said, due to toxins, traumatic brain injury, or internal brain disease.

“If I were involved in the case, I would say to the prosecutor, if she had not had an extensive MRI of the brain performed, it would be a negligent evaluation,” said Granacher.

He also said tests of memory function and symptom validity tests should have been conducted. Since the records are sealed, it is not known if magnetic resonance imaging or any other tests were performed.

In their 2007 paper, “Amnesia and Crime,” in The Journal of the American Academy of Psychiatry and the Law, Dominique Bourget and Laurie Whitehurst of the University of Ottawa, along with other researchers, report that there are claims of amnesia in 10 to 70 percent of homicide cases.

In a response to their paper, Hal Wortzel and David Arciniegas of the University of Colorado School of Medicine underscore the importance of the neurobiology of memory in forensic psychiatry. They write that amnesia for entire events, without even a hazy memory, is “inconsistent with the effects of stress on memory formation.”

Granacher said the pool of neuropsychiatrists with the proper medical knowledge is limited and forensic psychiatrists are often poorly trained.

“The science is there but usually for financial reasons courts do not have access to people like me because they offer such pitiful amounts of money that I and others are not willing to do the work,” said Granacher.

Alford plea

The Alford plea used by Zetzsche, like nolo contendere, does not admit guilt but pleads guilty, effectively waiving a trial. Unlike nolo contendere, the Alford plea allows for the defendant to declare his or her innocence while still accepting that the case for a guilty conviction is strong, and the defendant cannot plead differently on the same facts in a civil case.

The Alford plea was first accepted by a trial court and upheld in United States Supreme Court in 1970.

According to the court’s opinion, written by Justice Byron White, Henry Alford was indicted for first-degree murder in North Carolina, punishable under the state’s law with the death penalty or life imprisonment if convicted by a jury, and life imprisonment with a guilty plea. For second-degree murder, a defendant faced two to 30 years in prison.

There were no eye witnesses to the crime, Byron wrote, but testimony for the state’s case said that Alford left his house with a gun shortly before the crime and said he planned to kill the victim, and that he returned, saying he had done so. Alford testified that he did not commit the murder, but would plead guilty, having been advised by his attorney, to avoid the death penalty and limit his sentence to a 30-year maximum for second-degree murder.

White wrote in the Supreme Court’s opinion that there was no constitutional requirement for a defendant to admit guilt in order to be sentenced for a crime, only to waive a trial; a defendant’s claim of innocence makes no difference in the plea when there is a strong case against the defendant. The court also wrote that states could prohibit the accepting of lesser sentences, but it was not required by the Fourteenth Amendment.

The first section of the Fourteenth Amendment reads: “All persons born or naturalized in the United States, and subject to the jurisdiction thereof, are citizens of the United States and of the state wherein they reside. No state shall make or enforce any law which shall abridge the privileges or immunities of citizens of the United States; nor shall any state deprive any person of life, liberty, or property, without due process of law; nor deny to any person within its jurisdiction the equal protection of the laws.”

The court cited Brady v. United States in determining that choosing among alternatives to avoid the death penalty, as long as it was a “voluntary and intelligent choice,” was not a violation of the Fifth Amendment.

The Fifth Amendment grants constitutional rights of a grand jury presentments and indictment in capital crimes, against double jeopardy, against self-incrimination, and guarantees a fair trial for a criminal defendant, and just compensation when the government seizes private property.