Newspapers are reliable messengers

“An unreliable messenger can cause a lot of trouble. Reliable communication permits progress.” That’s a thought as old as the Bible. And it still rings true.

We wrote last week about a kerfuffle in Guilderland’s Democratic Party Committee. Some members were complaining — two of them wrote letters that we printed — that they had not known the caucus was going to be held weeks earlier than originally scheduled.

The second letter writer, Barry Nelson Uznitsky, a member of the Democratic committee, hadn’t even known the caucus had been held until he read the first letter in our Aug. 6 edition, after the caucus was held. He surmised party leaders wanted only committee members who would support their choice of candidates to attend.

Our Guilderland reporter, Anne Hayden Hardwood, looked into the matter and was told the reason for the early caucus was that the party chairman, David Bosworth, was hospitalized. He had been gravely ill, said the chosen candidate for supervisor, Peter Barber, and wanted the caucus “to be held while he was still around.”

Jean Cataldo, a Democrat and the town clerk, said there is a minimum requirement of 10 notifications for a caucus. She provided us with a sworn affidavit that she posted notices in 17 different locations two weeks before the July 23 caucus.

So, the Democrats holding the caucus had followed the letter of the State Election Law, and Uznitsky’s contention that actions taken at the caucus were invalid was not true.

But what about the intent of the law?

The intent is to inform, and the law has not kept up with the times. In our lifetime, there has been more change in modes of communication than in prior centuries combined.

How many people frequent the 17 places on the list of notices posted by the clerk? There is no central meeting place, no town square, in Guilderland.

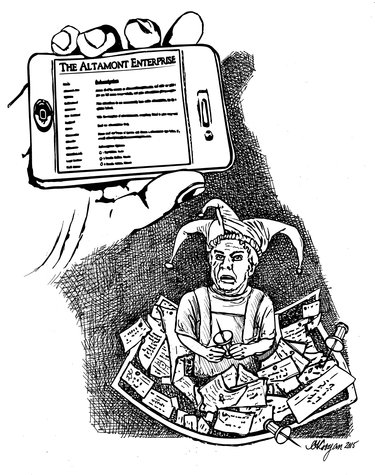

And how many people get their information now from physical bulletin boards? Customers of Mike’s Diner or Stewart’s where the notices were posted might not even glance at a bulletin board; they may be too busy reading text messages on their cell phones.

That brings us to the point of reliable communication in the modern era. In the not-too-distant past, committee members used to get phone calls telling them of caucus dates; such calls could, indeed, be time-consuming to make.

But as technology gallops forward, we bet most Democratic Committee members in Guilderland have cell phones or computers and that lists of members could easily include these email addresses. With one stroke on a keyboard, a single message could be sent to all the committee members. The argument that it is too costly to inform people this way does not hold.

In the Helderberg town of Knox, the Democratic caucus this summer was packed. The Knox party chairman, Nicholas Viscio, wrote us a letter praising the turnout as the longtime incumbent supervisor, Michael Hammond, was unsuccessfully challenged for the nod.

Viscio told our Hilltown reporter, Marcello Iaia, that “personal contact” is the best way to publicize a caucus. Viscio said he didn’t rally; he told only his friends and family. However, Vasilios Lefkaditis, Hammond’s challenger, told us that that was precisely the problem — all the usual suspects came to the caucus, he said, and the incumbent got the nod. Lefkaditis said he, himself, learned about the caucus only “at the 11th hour.”

Social networks operate that way, whether electronically or through word of mouth: People tell the people they know.

Newspapers can solve this problem by providing blanket notification. Legal notices are required for many municipal functions, but not for party caucuses. Although not required, responsible parties post notification in a newspaper. Berne Democrats, for example, posted a legal notice with us for their caucus; for one week, it cost less than $12.

We think that’s a good idea, not because we make a lot of money off of the notices; we don't. The rate, which hasn’t been raised in years, is set by the state legislature, based on a paper’s circulation.

A newspaper, in any community where one is still viable, is the single source of blanket notification — a place where people from all walks of life, all social and economic backgrounds, all genders, all races, and all creeds, have access.

For those who only read news online, or for those who can’t or won’t spend a dollar on a newspaper, The Enterprise posts legal notices on its website, where they can be read free of charge. After people read a notice, they can use their mouths or electronic devices to spread the word.

We know legal notices work. In a dust-up this month among commissioners in the Berne Fire District, one commissioner had a legal notice placed soliciting bids for a new ladder truck. The town supervisor was on the phone the next day to the district chairman to ask why. In the 48 hours since the notice ran, the chairman told us, his phone had been ringing off the hook.

Ultimately, the commissioner who had the ad placed apologized; the chairman said that now, with plans for a new firehouse underway, wasn’t a good time to burden taxpayers further.

Political parties and elected representatives need to look beyond the minimum requirements of the law. Our letters pages provide an open forum for the exchange of ideas on issues important to our community. They run free of charge. We would have welcomed a letter, for example, explaining that the Democratic Committee in Guilderland moved up its caucus date to accommodate its ailing chairman. Had someone notified our newsroom, we may well have written a story about it — before rather than after the caucus.

An unreliable messenger can cause a lot of trouble, as Proverbs states. And, in this day and age, bulletin boards are not reliable messengers; newspapers are.

— Melissa Hale-Spencer