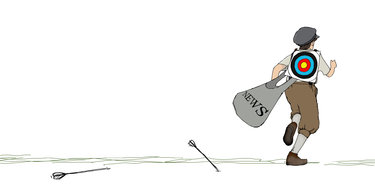

Targeting the news won’t solve our problems

Democracy works best when citizens are informed and thereby empowered to act.

Guilderland’s elected representatives at their televised Nov. 18 town board meeting called our headline, “Town taxes to jump 162% for Altamont residents,” both “misleading” and “salacious.”

It was neither. It accurately described the tax hike village residents face for next year with the first sentence stating that the $48 million budget will decrease the average property tax bill in town by $16 but will increase the tax bill for Altamont village residents by about $240.

No other media reported on the hike so, without our story, Altamont residents or even Altamont’s elected leaders, wouldn’t have known.

The story went on to explain that the hike was caused by a comptroller-directed shift in how sales-tax revenues — the major source of income for municipalities in Albany County — could be allocated. This week’s Enterprise includes a story we posted on Nov. 26, the day the state comptroller’s office released its report on the required shift along with the supervisor’s response on why he believes it is unfair.

Altamont’s mayor commended the Enterprise coverage, explaining that is how she and village trustees found out about the tax hike. She also noted that, in the same edition, both the town and village boards were allowed to explain their views in letters to the editor.

The attack that Donald Trump launched on the First Amendment during his first term — disparaging truth as “fake news” and labeling journalists the “enemy of the American people” — has intensified in his second term, affecting journalists here and everywhere.

The Society of Professional Journalists put out a statement on Nov. 19, condemning Trump’s two recent attacks on journalists, calling for “the public to hold all elected officials accountable for their respect — or disregard — for press freedom.”

ABC News Chief White House Correspondent Mary Bruce had asked the Saudi crown prince why Americans should trust him after United States intelligence had concluded he orchestrated the brutal murder of Washington Post columnist Jamal Khashoggi.

Rather than let the crown prince answer, Trump cut in to belittle the question and chastise Bruce for “embarrassing our guest.”

“When reporters ask hard questions about the murder of a fellow journalist, that is not an embarrassment,” said Caroline Hendrie, the executive director of the Society of Professional Journalists. “What’s embarrassing is a leader trying to silence those questions.”

Days later, Trump insulted Bloomberg reporter Catherine Lucey when she pressed him on releasing files related to the investigation of Jeffrey Epstein.

“Quiet!” Trump said. “Quiet, piggy.”

“Every attack on a journalist chips away at our democracy,” Hendrie said. “Every time we push back, we strengthen it.”

The idea of killing the messenger is not a new one. Rulers with absolute power have, over the course of history, frequently done so.

As the ancient Greek biographer Plutarch — who recorded the lives of famous Greeks and Romans from centuries before — writes in the Life of Lucullus, describing events leading up to the Roman leader’s assault on the Armenian king Tigranes, as translated by John Dryden, “The first messenger that gave notice of Lucullus’s coming was so far from pleasing Tigranes that he had his head cut off for his pains; and no man daring to bring further information, without any intelligence at all, Tigranes sat while war was already blazing around him, giving ear only to those who flattered him ….”

Earlier, in Plutarch’s telling, Appius Clodius, who was the brother of Lucullus’s wife, had addressed King Tigranes frankly, which angered him, and he was also angry that Appius had called him only “king” and not “king of kings.”

Plutarch writes, again in Dryden’s translation, “Insomuch that though Tigranes endeavored to receive him with a smooth countenance and a forced smile, he could not dissemble his discomposure to those who stood about him at the bold language of the young man; for it was the first time, perhaps, in 25 years, the length of his reign, or, more truly, of his tyranny, that any free speech had been uttered to him.”

The United States of America does not have a king. We have a republic in which the sovereign power rests with the people and in which free speech is essential if people are to be informed to make wise choices.

History has shown time and time again that a leader surrounding himself only with sycophants, as Tigranes did, is not likely to have his people prosper in the long run.

In our own country, Abraham Lincoln won the Republican nomination for president in 1860 over three much more affluent, politically experienced, and well known men: William Seward, Edward Bates, and Salmon Chase. After being elected, Lincoln appointed his three rivals to his cabinet: Seward as secretary of state, Bates as attorney general, and Chase as secretary of the treasury.

Lincoln said that, in a time of peril, the nation needed its strongest leaders. He benefited and strengthened his leadership at a critical time by listening to varied views.

Leaders in the great American experiment of democracy benefit at every level of government by being informed about varied viewpoints and understanding differing opinions. Citizens benefit, too. That is why, with the story on the tax hike for Altamont, for example, we printed lengthy letters from both the village board and the town board so readers could understand both sides.

It is not an easy task for a politician at any level to read or hear criticism of his or her views or actions.

Our paper thoroughly covers local news, often neglected elsewhere, sometimes angering local leaders uncomfortable with the focus on their deeds. Over the decades, we’ve had municipalities withdraw legal notices in the paper of record to try to undermine us. We’ve had elected boards hold illegal secret meetings to escape our coverage.

We’ve had elected leaders refuse to take our calls or literally run away from one of our reporters, unwilling to answer questions related to matters of public interest. We’ve been called liars and all manner of epithets, some unprintable. We’ve been spit on and had our mailbox blown up.

During these assaults, we’ve taken solace in the wisdom expressed by Walter Lippmann. “It is only human,” he wrote, “for officials to feel that unfavorable news or critical comment is biased, incompetent, and misleading. There is no denying the sincerity of their complaints and there is no use pretending that any newspaperman can regularly give the whole objective truth about all complicated and controverted questions.

“The theory of a free press is that the truth will emerge from free reporting and free discussion, not that it will be presented perfectly and instantly in any one account.”

That last sentence is one we’ve repeated countless times over the last several decades to leaders and readers alike who are unhappy with our reporting, in which we strive to be objective, or with our editorials, in which we write our opinions based on facts.

We follow up with stories when there is more truth to be told, just as we did this week with a story on the state audit. And we urge our readers — those who are incensed as well as those who are inspired by our words — to join the discussion.

We run many pages of letters every week — and pages are dear in this era when tariffs have increased the cost of newsprint. But we believe it is essential for the various factions of our community to communicate with one another. We correct the facts if need be and let the opinions run free.

We believe this is the way to build bridges across the ever-widening divides in our nation. We provide a common ground for civil discourse, which can become a means of solving problems. Without first revealing and describing a problem, as uncomfortable as that may make some leaders, it cannot be solved.

Our stories, coupled with editorials, have moved our readers and brought about change for the good: a girl sodomized by her father got her day in court, toxic wastes were removed from an old Army dump, skewed tax rolls were righted, a big-box plan was thwarted — all because our readers were empowered with knowledge.

We, as journalists, cannot be a friend of someone we cover, nor an enemy. We have to understand as best we can where the truth lies and report it as fairly as we are able.

If this makes a leader disparage our work, so be it. We won’t respond in kind. We are saddened and alarmed that so many places in the United States are now without newspapers to call their own. And many of those news organizations that remain are so short-staffed that much local news goes unreported.

If democracy is to survive and prosper, the people need to be informed. At the most basic level, how can a voter choose wisely if she or he doesn’t have access to information about candidates for local government or school boards?

Citizens have a responsibility to read, to listen to, to look for, and to embrace news from sources that will widen their perspectives and understanding. After all, since it is the people who hold sovereign power in our democracy, they must not be like King Tigranes and listen only to those with whom they agree. They must not kill the messengers — the journalists who tell the truth.

Every day, we are grateful for the people who read our newspaper or our website. We pledge to keep up our side of the bargain, informing the public. We trust the public will respond in kind. Our future as a democracy depends on it.